Babakotia

| Babakotia Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Babakotia radofilai skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Strepsirrhini |

| Family: | †Palaeopropithecidae |

| Genus: | †Babakotia Godfrey et al., 1990[2] |

| Species: | †B. radofilai

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Babakotia radofilai Godfrey et al., 1990[1]

| |

| |

| Subfossil sites forBabakotia radofilai[3] | |

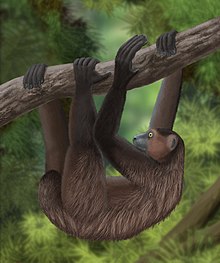

Babakotia is an extinct

Babakotia radofilai and all other sloth lemurs share many traits with living

Etymology

The name of the genus Babakotia derives from the Malagasy common name for the Indri, babakoto, a close relative of Babakotia. The species name, radofilai, was chosen in honor of French mathematician and expatriate Jean Radofilao, an avid spelunker who mapped the caves where remains of Babakotia radofilai were first found.[4]

Classification and phylogeny

Babakotia radofilai is the sole member of the

The first subfossil remains of Babakotia radofilai were discovered as part of a series of expeditions following upon discoveries of Jean Radofilao and two Anglo-Malagasy reconnaissance expeditions in 1981 and 1986–7.

Anatomy and physiology

Weighing between 16 and 20 kg (35 and 44 lb), Babakotia radofilai was a medium-sized lemur and noticeably smaller than the large sloth lemurs (Archaeoindris and Palaeopropithecus), but larger than the small sloth lemurs (Mesopropithecus).

| Babakotia placement within the lemur phylogeny[18][19][11] | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

All sloth lemurs have relatively robust skulls compared to the indriids,

The dental formula of Babakotia radofilai was the same as the other sloth lemurs and indriids: either 2.1.2.31.1.2.3[1][9] or 2.1.2.32.0.2.3 × 2 = 30.[3] It is unclear whether one of the teeth in the permanent dentition is an incisor or canine, resulting in these two conflicting dental formulae.[21] Regardless, the lack of either a lower canine or incisor results in a four-tooth toothcomb instead of the more typical six-tooth strepsirrhine toothcomb. Babakotia radofilai differed slightly from indriids in having somewhat elongated premolars. Its cheek teeth had broad shearing crests and crenulated enamel.[3]

Distribution and ecology

Like all other lemurs, Babakotia radofilai was

Based on its size, the morphology of its

Extinction

Because it died out relatively recently and is only known from subfossil remains, it is considered to be a modern form of Malagasy lemur.

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- ISBN 978-0-231-11013-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-66315-1.

- ^ a b Godfrey, L.R.; Simons, E.L.; Chatrath, P.J.; Rakotosamimanana, B. (1990). "A new fossil lemur (Babakotia, Primates) from northern Madagascar". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences. 2. 81: 81–87.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-881173-88-5.

- PMID 2807091.

- ^ Wilson, J.M.; Godrey, L.R.; Simons, E.L.; Stewart, P.D.; Vuillaume-Randriamanantena, M. (1995). "Past and present lemur fauna at Ankarana, N. Madagascar" (PDF). Primate Conservation. 16: 47–52.

- ^ S2CID 4834725. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-881173-08-3.

- PMID 1924371.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-226-30306-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-56098-682-9.

- ISBN 978-1-56098-682-9.

- PMID 11038588.

- PMID 10799257.

- S2CID 83737480.

- PMID 16110476.

- PMID 18245770. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- PMID 18442367.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-387-34585-7.

- ISBN 978-0-12-372576-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-536-74363-3.

- S2CID 7171105.

- ^ Godfrey, L.R.; Wilson, Jane M.; Simons, E.L.; Stewart, Paul D.; Vuillaume-Randriamanantena, M. (1996). "Ankarana: a window on Madagascar's Past". Lemur News. 2: 16–17.

- ^ Wilson, Jane M.; Godfrey, L.R.; Simons, E.L.; Stewart, Paul D.; Vuillaume-Randriamanantena, M. (1995). "Past and Present Lemur Fauna at Ankarana, N. Madagascar". Primate Conservation. 16: 47–52.

- PMID 12457853.

- S2CID 129808875.