Baby, Please Don't Go

| "Baby, Please Don't Go" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Single by Joe Williams' Washboard Blues Singers | |

| B-side | "Wild Cow Blues" |

| Released | 1935 |

| Recorded | Chicago, October 31, 1935 |

| Genre | Blues |

| Length | 3:22 |

| Label | Bluebird |

| Songwriter(s) | Traditional (J. Williams credited on record) |

| Producer(s) | Lester Melrose |

"Baby, Please Don't Go" is a traditional blues song that was popularized by Delta blues musician Big Joe Williams in 1935. Many cover versions followed, leading to its description as "one of the most played, arranged, and rearranged pieces in blues history" by French music historian Gérard Herzhaft.

After World War II,

In the 1960s, "Baby, Please Don't Go" became a popular

Background

"Baby, Please Don't Go" is likely an adaptation of "Long John", an old folk theme that dates back to the time of

Author Linda Dahl suggests a connection to a song with the same title by Mary Williams Johnson in the late 1920s and early 1930s.[4] However, Johnson, who was married to jazz-influenced blues guitarist Lonnie Johnson, never recorded it and her song is not discussed as influencing later performers.[1][3][5] Blues researcher Jim O'Neal notes that Williams "sometimes said that the song was written by his wife, singer Bessie Mae Smith a.k.a. Blue Belle and St. Louis Bessie."[3]

Original song

Big Joe Williams used an imprisonment theme for his October 31, 1935, recording of "Baby, Please Don't Go". He recorded it during his first session for

Now baby please don't go, now baby please don't go

Baby please don't go back to New Orleans, and get your cold ice cream

I believe there's a man done gone, I believe there's a man done gone

I believe there's a man done gone to the county farm, with a long chain on

The song became a hit and established Williams' recording career.[9] On December 12, 1941, he recorded a second version titled "Please Don't Go" in Chicago for Bluebird, with a more modern arrangement and lyrics.[10] Blues historian Gerard Herzhaft calls it "the most exciting version",[1] which Williams recorded using his trademark nine-string guitar. Accompanying him are Sonny Boy Williamson I on harmonica and Alfred Elkins on imitation bass (possibly a washtub bass).[11] Since both songs appeared before recording industry publications began tracking such releases, it is unknown which version was more popular. In 1947, he recorded it for Columbia Records with Williamson and Ransom Knowling on bass and Judge Riley on drums.[2] This version did not reach the Billboard Race Records chart,[12] but represents a move toward a more urban blues treatment of the song.

Later blues and R&B recordings

Big Joe Williams' various recordings inspired other blues musicians to record their interpretations of the song

In 1953, Muddy Waters recast the song as a Chicago-blues ensemble piece with Little Walter and Jimmy Rogers.[18] Chess Records originally issued the single with the title "Turn the Lamp Down Low", although the song is also referred to as "Turn Your Lamp Down Low",[3] "Turn Your Light Down Low",[14] or "Baby Please Don't Go".[e] He regularly played the song, several performances were recorded. Live versions appear on Muddy Waters at Newport 1960 and on Live at the Checkerboard Lounge, Chicago 1981 with members of the Rolling Stones.[19] AllMusic critic Bill Janovitz cites the influence of Waters' adaptation:

The most likely link between the Williams recordings and all the rock covers that came in the 1960s and 1970s would be the Muddy Waters 1953 Chess side, which retains the same swinging phrasing as the Williams takes, but the session musicians beef it up with a steady driving rhythm section, electrified instruments and Little Walter Jacobs wailing on blues harp.[20]

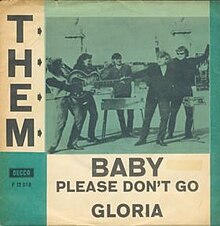

Van Morrison and Them rendition

| "Baby, Please Don't Go" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Them | ||||

| B-side | "Gloria" | |||

| Released |

| |||

| Recorded | October 1964 | |||

| Genre | Blues rock, garage rock, Proto-punk | |||

| Length | 2:40 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Songwriter(s) | Traditional (Williams credited) | |||

| Producer(s) | Bert Berns | |||

| Them singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Baby Please Don't Go" was one of the earliest songs recorded by Them, fronted by a 19-year-old Van Morrison. Their rendition of the song was derived from a version recorded by John Lee Hooker in 1949 as "Don't Go Baby".[21][f] Hooker's song later appeared on a 1959 album, Highway of Blues, which Van Morrison heard and felt was "something really unique and different" with "more soul" than he had previously heard.[21]

Recording and composition

Them recorded "Baby, Please Don't Go" for Decca Records in October 1964. Besides Morrison, there is conflicting information about who participated in the session. In addition to the group's original members (guitarist Billy Harrison, bassist Alan Henderson, drummer Ronnie Millings and keyboard player Eric Wrixon), others have been suggested: Pat McAuley on keyboards, Bobby Graham on a second drum kit, Jimmy Page on guitar,[22] and Peter Bardens on keyboards.[23] As Page biographer George Case notes, "There is a dispute over whether it is Page's piercing blues line that defines the song, if he only played a run Harrison had already devised, or if Page only backed up Harrison himself".[24] Morrison has acknowledged Page's participation in the early sessions: "He played rhythm guitar on one thing and doubled a bass riff on the other"[25] and Morrison biographer Johnny Rogan notes that Page "doubled the distinctive riff already worked out by Billy Harrison".[25]

Janovitz identifies the riff as "the backbone of the arrangement" and describes Henderson's contribution as an "amphetamine-rush, pulsing two-note bass line."[20][g] Music critic Greil Marcus comments that during the song's quieter middle passage "the guitarist, session player Jimmy Page or not, seems to be feeling his way into another song, flipping half-riffs, high, random, distracted metal shavings".[26][h] Them's blues rock arrangement is "now regarded justly as definitive", according to music writer Alan Clayson.[28]

Releases and charts

Decca released "Baby, Please Don't Go" as Them's second single on November 6, 1964.

The song was not included on Them's original British or American albums (

AC/DC version

| "Baby, Please Don't Go" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Albert, Sydney | ||||

| Genre | Blues rock | |||

| Length | 4:47 | |||

| Label | Albert | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Traditional (Williams credited) | |||

| Producer(s) | ||||

| AC/DC singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Baby, Please Don't Go" was a feature of AC/DC's live shows since their beginning.[40] Although they have expressed their interest and inspiration in early blues songs,[41] music writer Mick Wall identifies Them's adaptation of the song as the likely source.[42] In November 1974, Angus Young, Malcolm Young, and Bon Scott recorded it for their 1975 Australian debut album, High Voltage.[41] Tony Currenti is sometimes identified as the drummer for the song, although he suggests that it had been already recorded by Peter Clack.[43] Wall notes that producer George Young played bass for most of the album,[42] although Rob Bailey claims that many of the album's tracks were recorded with him.[44]

High Voltage and a single with "Baby, Please Don't Go" were released simultaneously in Australia in February 1975.[44][j] Albert Productions issued it as the single's B-side. However, the A-side "Love Song (Oh Jene)" was largely ignored and "Baby, Please Don't Go" began receiving airplay.[42] The single entered the chart at the end of March 1975[45] and peaked at number 10 in April.[46] AllMusic critic Eduardo Rivadavia called the song "positively explosive",[47] while music writer Dave Rubin described it as "primal blues rock".[48]

On March 23, 1975, one month after drummer

As soon as his vocals are about to begin he comes out from behind the drums dressed as a schoolgirl. And it was like a bomb went off in the joint; it was pandemonium, everybody broke out in laughter. [Scott] had a wonderful sense of humor.[49]

Scott mugs for the camera and, during the guitar solo/vocal improvization section, he lights a cigarette as he duels with Angus with a green mallet.

Aerosmith version

Recognition and legacy

"Baby, Please Don't Go" is recognized as a

In 1967, the Amboy Dukes recorded the song for their self-titled debut album. An album review mentions Them's version, but adds that the Amboy Dukes' "Ted Nugent and the boys totally twist it to their point-of-view, even tossing a complete Jimi Hendrix [guitar line from "Third Stone from the Sun"] nick into the mix."[59] Released as a single, it reached number 106 on Billboard's extended "Bubbling Under the Hot 100" chart.[60] In 1969, Ten Years After included some lyrics from "Baby, Please Don't Go" during their performance of "I'm Going Home" at the Woodstock festival in Bethel, New York.[61] Alvin Lee's 10-minute guitar workout was a highlight of the event's 1970 documentary film,[62] which "would cement their reputation for decades to come".[63]

Notes

- ^ An earlier "I'm Alabama Bound", with its own recording history, was published by Robert Hoffman in 1909.

- ^ The sheet music includes a 1944 copyright date, indicating a later version of the song[7] (Williams' 1935 recording is in the key of B).

- ^ The Orioles' original 1952 Jubilee single lists the songwriters as "Strutt – Alexander",[15] while a compilation issued by the label in 1962 lists the writers as "T. Skye – R. C. Gardner"[16]

- ^ Music historian Larry Birbaum suggested that the Orioles' 1951 version inspired James Brown's first hit "Please, Please, Please" (1956).[5]

- ^ Muddy Waters' original Chess single lists the songwriters as "Strutt, Alexander", although reissues credit "McKinley Morganfield" (his legal name). The song is registered as "Turn the Lamps [sic] Down Low" with Joseph Lee Williams as the songwriter. ISWC T-070.278.618-2.

- ^ John Lee Hooker was listed as "Texas Slim" on the single "Don't Go Baby" (King 4334).

- ^ Janovitz claims that Henderson's bass line "was later lifted by Golden Earring for 'Radar Love'".[20]

- ^ Beginning about 1:22 in Them's recording, bassy-sounding riffs appear.[27]

- ^ "Baby Please Don't Go" and "Gloria" remained at number one for three weeks (April 14, 21, and 28, 1965) on KRLA's "Tunedex" chart.[34] In May 1966, Them performed an "unprecedented" 18-night engagement at the West Hollywood Whisky a Go Go nightclub.[35]

- ^ The Albert Productions AC/DC single misidentified the songwriter as Big Bill Broonzy.[44]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g Herzhaft 1992, p. 437.

- ^ a b c d Garon 2004, p. 39.

- ^ a b c d e f g h O'Neal, Jim (1992). "1992 Hall of Fame Inductees: "Baby Please Don't Go" – Big Joe Williams (Bluebird 1935)". The Blues Foundation. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ^ Dahl 1984, p. 110.

- ^ a b Birnbaum 2012, p. 302.

- ^ a b Hal Leonard 1995, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Hal Leonard 1995, p. 17.

- ^ Gioia 2008, p. 130.

- ^ Herzhaft 1992, p. 381.

- ^ Demetre 1994, p. 23.

- ^ Demetre 1994, p. 29.

- ^ Whitburn 1988, pp. 444–445.

- ^ Escott 2002, p. 54.

- ^ a b Garon 2004, p. 40.

- ^ Please Don't Go (single notes). Jubilee Records. 1952. Single label. 45-5065.

- ^ The Cadillacs Meet the Orioles (Album notes). New York City: Jubilee Records. 1962. LP side one label. JGM 1117.

- ^ Greenwald, Matthew. "Mose Allison: Baby Please Don't Go, Composed by Big Joe Williams". AllMusic. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ Palmer 1989, p. 28.

- ^ Gordon 2002, p. 266.

- ^ a b c Janovitz, Bill. "Big Joe Williams: 'Baby Please Don't Go' – Review". AllMusic. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ a b Murray 2002, pp. 212, 302.

- ^ a b Thompson 2008, p. 303.

- ^ Strong 2002, eBook.

- ^ Case 2007, p. 35.

- ^ a b Rogan 2006, pp. 101, 111.

- ^ Marcus 2010, eBook.

- ^ Them (1964). Baby, Please Don't Go (Song recording). London: Decca Records. Event occurs at 1:22. F.12018.

- ^ Clayson 2006, p. 61.

- ^ a b "Them – Singles". Official Charts. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ^ Billboard 1965a, p. 39.

- ^ Billboard 1965b, p. 24.

- ^ Billboard 1965c, p. 26.

- ^ Priore 2007, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Beat 1965a, p. 4Beat 1965b, p. 4Beat 1965c, p. 3

- ^ Priore 2007, p. 25

- ^ CashBox 1965, p. 18.

- ^ "Them: 'Baby Please Don't Go' – Appears On". AllMusic. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ Carlson, Dean. "Wild at Heart [Original Soundtrack] – Review". AllMusic. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ Viglione, Joe. "John Lee Hooker: Come and See About Me – Review". AllMusic. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ Walker 2011, p. 135.

- ^ a b c d Perkins 2011, eBook.

- ^ a b c Wall 2013, eBook.

- ^ Fink 2014, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Walker 2011, p. 139.

- ^ Walker 2011, p. 145.

- ^ Walker 2011, p. 148.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "AC/DC: High Voltage (Australia) – Review". AllMusic. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ^ Rubin 2015, eBook.

- ^ a b c Miller 2009, eBook.

- ^ a b c Bonomo 2010, eBook.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Aerosmith: Honkin' on Bobo – Review". AllMusic. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ^ Billboard 2004, pp. 13, 15.

- Gannett Company. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- Billboard.com. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ "Aerosmith: 'Baby Please Don't Go' Video Posted Online". Blabbermouth.net. May 20, 2004. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- A.H. Belo. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- ^ Stingley, Mick (October 14, 2010). "Aerosmith/The J. Geils Band – Concert Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- ^ "500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. 1995. Archived from the original on April 22, 2007. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ^ Viglione, Joe. "The Amboy Dukes – Review". AllMusic. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ Whitburn 2008, p. 17.

- ^ Moore 2004, p. 81.

- ^ Jurek, Thom. "Woodstock – Review". AllMusic. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ Deming, Mark. "Ten Years After – Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

Print sources

- "KRLA Tunedex". KRLA Beat. April 14, 1965.

- "KRLA Tunedex". KRLA Beat. April 21, 1965.

- "KRLA Tunedex". KRLA Beat. April 28, 1965.

- "Single Reviews – Chart Specials". ISSN 0006-2510.

- "Bubbling Under the Hot 100". ISSN 0006-2510.

- "Bubbling Under the Hot 100". ISSN 0006-2510.

- "'Honk' if You Love Old Aerosmith". ISSN 0006-2510.

- "CashBox Record Reviews". Cash Box. Vol. 26, no. 28. January 30, 1965.

- Birnbaum, Larry (2012). Before Elvis: The Prehistory of Rock 'n' Roll. Lanham, Maryland: ISBN 978-0-8108-8629-2.

- ISBN 978-1441141583.

- Case, George (2007). Jimmy Page: Magus, Musician, Man – An Unauthorized Biography. ISBN 978-1-4234-0407-1.

- Clayson, Alan (2006). Led Zeppelin: The Origin of the Species. Chrome Dreams. ISBN 1-84240-345-1.

- Dahl, Linda (1984). Stormy Weather: The Music and Lives of a Century of Jazzwomen. ISBN 0-87910-128-8.

- Demetre, Jacques (1994). The Prewar Blues Story 1926–1943 (CD compilation booklet). Various artists. Best of Blues. OCLC 874878605. Best of Blues 20.

- OCLC 52004950. Ace ABOXCD 8.

- Fink, Jesse (2014). The Youngs: The Brothers Who Built AC/DC. New York City: ISBN 978-1466865204.

- Garon, Paul (2004). "Baby Please Don't Go/Don't You Leave Me Here". In Komara, Edward (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Blues. New York City: ISBN 978-1135958329.

- ISBN 978-0-393-33750-1.

- Gordon, Robert (2002). Can't Be Satisfied: The Life and Times of Muddy Waters. Boston, Massachusetts: ISBN 0-316-32849-9.

- Hal Leonard (1995). "Baby Please Don't Go". The Blues. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: ISBN 0-79355-259-1.

- Herzhaft, Gerard (1992). "Baby, Please Don't Go". Encyclopedia of the Blues. Fayetteville, Arkansas: ISBN 1-55728-252-8.

- ISBN 978-1-58648-821-5.

- Miller, Heather (2009). AC/DC: Hard Rock Band. Enslow. ISBN 978-0766030312.

- Moore, Allan F. (2004). "The Contradictory Aesthetics of Woodstock". In Bennett, Andy (ed.). Remembering Woodstock. New York City: ISBN 978-0-7546-0714-4.

- ISBN 978-0-312-27006-3.

- Palmer, Robert (1989). Muddy Waters: Chess Box (Box set booklet). OCLC 154264537. CHD3-80002.

- Perkins, Jeff (2011). AC/DC – Uncensored on the Record. Coda Books. ISBN 978-1908538543.

- ISBN 978-1-906002-04-6.

- ISBN 978-0-09-943183-1.

- Rubin, Dave (2015). Inside Rock Guitar: Four Decades of the Greatest Electric Rock Guitarists. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: ISBN 978-1495056390.

- ISBN 978-1-84195-312-0.

- Thompson, Gordon (2008). Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out. ISBN 978-0-19-533318-3.

- ISBN 978-1891241864.

- ISBN 978-1250038753.

- ISBN 0-89820-068-7.

- ISBN 978-0898201758.