Bacterial conjugation

Bacterial conjugation is the transfer of genetic material between bacterial cells by direct cell-to-cell contact or by a bridge-like connection between two cells.[1] This takes place through a pilus.[2] It is a parasexual mode of reproduction in bacteria.

It is a mechanism of horizontal gene transfer as are transformation and transduction although these two other mechanisms do not involve cell-to-cell contact.[4]

Classical E. coli bacterial conjugation is often regarded as the bacterial equivalent of

The genetic information transferred is often beneficial to the recipient. Benefits may include

.Conjugation in Escherichia coli by spontaneous zygogenesis[7] and in Mycobacterium smegmatis by distributive conjugal transfer[8][9] differ from the better studied classical E. coli conjugation in that these cases involve substantial blending of the parental genomes.

History

The process was discovered by Joshua Lederberg and Edward Tatum[10] in 1946.

Mechanism

Conjugation diagram

- Donor cell produces pilus.

- Pilus attaches to recipient cell and brings the two cells together.

- The mobile plasmid is nicked and a single strand of DNA is then transferred to the recipient cell.

- Both cells synthesize a complementary strand to produce a double stranded circular plasmid and also reproduce pili; both cells are now viable donor for the F-factor.[1]

The

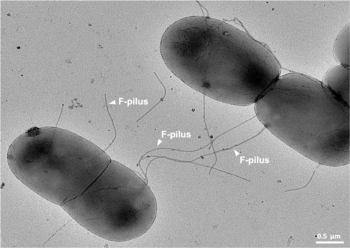

Among other genetic information, the F-plasmid carries a tra and trb locus, which together are about 33 kb long and consist of about 40 genes. The tra locus includes the pilin gene and regulatory genes, which together form pili on the cell surface. The locus also includes the genes for the proteins that attach themselves to the surface of F− bacteria and initiate conjugation. Though there is some debate on the exact mechanism of conjugation it seems that the pili are the structures through which DNA exchange occurs. The F-pili are extremely resistant to mechanical and thermochemical stress, which guarantees successful conjugation in a variety of environments.[11] Several proteins coded for in the tra or trb locus seem to open a channel between the bacteria and it is thought that the traD enzyme, located at the base of the pilus, initiates membrane fusion.

When conjugation is initiated by a signal the

If the F-plasmid that is transferred has previously been integrated into the donor's genome (producing an Hfr strain ["High Frequency of Recombination"]) some of the donor's chromosomal DNA may also be transferred with the plasmid DNA.[4] The amount of chromosomal DNA that is transferred depends on how long the two conjugating bacteria remain in contact. In common laboratory strains of E. coli the transfer of the entire bacterial chromosome takes about 100 minutes. The transferred DNA can then be integrated into the recipient genome via homologous recombination.

A cell culture that contains in its population cells with non-integrated F-plasmids usually also contains a few cells that have accidentally integrated their plasmids. It is these cells that are responsible for the low-frequency chromosomal gene transfers that occur in such cultures. Some strains of bacteria with an integrated F-plasmid can be isolated and grown in pure culture. Because such strains transfer chromosomal genes very efficiently they are called Hfr (high frequency of recombination). The E. coli genome was originally mapped by interrupted mating experiments in which various Hfr cells in the process of conjugation were sheared from recipients after less than 100 minutes (initially using a Waring blender). The genes that were transferred were then investigated.

Since integration of the F-plasmid into the E. coli chromosome is a rare spontaneous occurrence, and since the numerous genes promoting DNA transfer are in the plasmid genome rather than in the bacterial genome, it has been argued that conjugative bacterial gene transfer, as it occurs in the E. coli Hfr system, is not an evolutionary adaptation of the bacterial host, nor is it likely ancestral to eukaryotic sex.[14]

Spontaneous zygogenesis in E. coli

In addition to classical bacterial conjugation described above for E. coli, a form of conjugation referred to as spontaneous zygogenesis (Z-mating for short) is observed in certain strains of E. coli.[7] In Z-mating there is complete genetic mixing, and unstable diploids are formed that throw off phenotypically haploid cells, of which some show a parental phenotype and some are true recombinants.

Conjugal transfer in mycobacteria

Conjugation in Mycobacteria smegmatis, like conjugation in E. coli, requires stable and extended contact between a donor and a recipient strain, is DNase resistant, and the transferred DNA is incorporated into the recipient chromosome by homologous recombination. However, unlike E. coli Hfr conjugation, mycobacterial conjugation is chromosome rather than plasmid based.[8][9] Furthermore, in contrast to E. coli Hfr conjugation, in M. smegmatis all regions of the chromosome are transferred with comparable efficiencies. The lengths of the donor segments vary widely, but have an average length of 44.2kb. Since a mean of 13 tracts are transferred, the average total of transferred DNA per genome is 575kb.[9] This process is referred to as "Distributive conjugal transfer."[8][9] Gray et al.[8] found substantial blending of the parental genomes as a result of conjugation and regarded this blending as reminiscent of that seen in the meiotic products of sexual reproduction.

Conjugation-like DNA transfer in hyperthermophilic archaea

Hyperthermophilic archaea encode pili structurally similar to the bacterial conjugative pili.[15] However, unlike in bacteria, where conjugation apparatus typically mediates the transfer of mobile genetic elements, such as plasmids or transposons, the conjugative machinery of hyperthermophilic archaea, called Ced (Crenarchaeal system for exchange of DNA)[16] and Ted (Thermoproteales system for exchange of DNA),[15] appears to be responsible for the transfer of cellular DNA between members of the same species. It has been suggested that in these archaea the conjugation machinery has been fully domesticated for promoting DNA repair through homologous recombination rather than spread of mobile genetic elements.[15] In addition to the VirB2-like conjugative pilus, the Ced and Ted systems include components for the VirB6-like transmembrane mating pore and the VirB4-like ATPase.[15]

Inter-kingdom transfer

Bacteria related to the

The Ti and Ri plasmids can also be transferred between bacteria using a system (the tra, or transfer, operon) that is different and independent of the system used for inter-kingdom transfer (the vir, or virulence, operon). Such transfers create virulent strains from previously avirulent strains.[citation needed]

Genetic engineering applications

Conjugation is a convenient means for

See also

- Sexual conjugationin algae and ciliates

- Transfection

- Triparental mating

- Zygotic induction

References

- ^ PMID 21413277.

- ^ Dr.T.S.Ramarao M.sc, Ph.D. (1991). B.sc Botany-Volume-1.

- ^ Patkowski, Jonasz (21 April 2023). "F-pilus, the ultimate bacterial sex machine". Nature Portfolio Microbiology Community.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7167-3520-5. Archived from the original on 2020-02-08. Retrieved 2023-08-11.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link - ^ ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- PMID 21413277.

- ^ PMID 12949181.

- ^ PMID 23874149.

- ^ PMID 25505644.

- S2CID 1826960.

- PMID 37019921.

- PMID 17630285.

- ^ "Genetic Exchange". www.microbiologybook.org. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- PMID 18295550.

- ^ PMID 36750723.

- PMID 26884154.

- S2CID 38483513.

- S2CID 4351266.

- PMID 11172043.

- S2CID 27160.

- PMID 25897682.

- PMID 16157861.

External links

- Bacterial conjugation (a Flash animation)