Bal des Ardents

The Bal des Ardents (Ball of the Burning Men

The ball was one of a series of events organised to entertain the king, who the previous summer had suffered an attack of insanity. The event undermined confidence in Charles' capacity to rule; Parisians considered it proof of courtly decadence and threatened to rebel against the more powerful members of the nobility. The public's outrage forced the king and his brother Orléans, whom a contemporary chronicler accused of attempted regicide and sorcery, to offer penance for the event.

Charles's wife,

Background

In 1380, after the death of his father

In 1392, Charles suffered the first in a lifelong series of attacks of insanity, manifested by an "insatiable fury" at the attempted assassination of the

On a hot August day outside Le Mans, accompanying his forces on the way to Brittany, without warning Charles drew his weapons and charged his own household knights including his brother Louis I, Duke of Orléans—with whom he had a close relationship—crying, "Forward against the traitors! They wish to deliver me to the enemy!"[8] He killed four men[9] before his chamberlain grabbed him by the waist and subdued him, after which he fell into a coma that lasted for four days. Few believed he would recover; his uncles, the dukes of Burgundy and Berry, took advantage of the King's illness and quickly seized power, re-established themselves as regents, and dissolved the Marmouset council.[7]

The comatose king was returned to Le Mans, where Guillaume de Harsigny—a venerated and well-educated 92-year-old physician—was summoned to treat him. After Charles regained consciousness and his fever subsided, he was returned to Paris by Harsigny, moving slowly from castle to castle with periods of rest in between. Late in September Charles was well enough to make a pilgrimage of thanks to Notre Dame de Liesse near Laon after which he returned again to Paris.[7]

Charles' sudden onset of insanity was seen by some as a sign of divine anger and punishment, and by others as the result of

In

The common people thought the extravagances excessive yet loved their young king, whom they called Charles le bien-aimé (the well-beloved). Blame for unnecessary excess and expense was directed at the foreign queen, who was brought from

Bal des Ardents and aftermath

On 28 January 1393, Isabeau held a

According to historian Jan Veenstra the men capered and howled "like wolves", spat obscenities and invited the audience to guess their identities while dancing in a "diabolical" frenzy.[16] Charles's brother Orléans arrived with Philippe de Bar, late and drunk, and they entered the hall carrying lit torches. Accounts vary, but Orléans may have held his torch above a dancer's mask to determine his identity when a spark fell, setting fire to the dancer's leg.[1] In the 17th century, William Prynne wrote of the incident that "the Duke of Orleance ... put one of the Torches his servants held so neere the flax, that he set one of the Coates on fire, and so each of them set fire on to the other, and so they were all in a bright flame",[17] whereas a contemporary chronicle stated that he "threw" the torch at one of the dancers.[2]

Isabeau, knowing that her husband was one of the dancers, fainted when the men caught fire. Charles, however, was standing at a distance from the other dancers, near his 15-year-old aunt Joan, Duchess of Berry, who swiftly threw her voluminous skirt over him to protect him from the sparks.[1] Sources disagree as to whether the duchess moved into the dance and drew the king aside to speak to him, or whether the king moved away toward the audience. Froissart wrote that "The King, who proceeded ahead of [the dancers], departed from his companions ... and went to the ladies to show himself to them ... and so passed by the Queen and came near the Duchess of Berry".[18][19]

The scene soon descended into chaos; the dancers shrieked in pain as they burned in their costumes, and the audience, many of them also sustaining burns, screamed as they tried to rescue the burning men.

The citizens of Paris, angered by the event and at the danger posed to their monarch, blamed Charles' advisors. A "great commotion" swept through the city as the populace threatened to depose the king's uncles and kill dissolute and depraved courtiers. Greatly concerned at the popular outcry and worried about a repeat of the

Froissart's chronicle of the event places blame directly on Orléans. He wrote: "And thus the feast and marriage celebrations ended with such great sorrow ... [Charles] and [Isabeau] could do nothing to remedy it. We must accept that it was no fault of theirs but of the duke of Orléans."

The Bal des Ardents added to the impression of a court steeped in extravagance, with a king in delicate health and unable to rule. Charles' attacks of illness increased in frequency such that by the end of the 1390s his role was merely ceremonial. By the early 15th century he was neglected and often forgotten, a lack of leadership that contributed to the decline and fragmentation of the Valois dynasty.[23] In 1407, Philip of Burgundy's son, John the Fearless, had his cousin Orléans assassinated because of "vice, corruption, sorcery, and a long list of public and private villainies"; at the same time Isabeau was accused of having been the mistress of her husband's brother.[24] Orléans' assassination pushed the country into a civil war between the Burgundians and the Orléanists (known as the Armagnacs) which lasted for several decades. The vacuum created by the lack of central power and the general irresponsibility of the French court resulted in it gaining a reputation for lax morals and decadence that endured for more than 200 years.[25]

Folkloric and Christian representations of wild men

Veenstra writes in Magic and Divination at the Courts of Burgundy and France that the Bal des Ardents reveals the tension between Christian beliefs and the latent paganism that existed in 14th-century society. According to him, the event "laid bare a great cultural struggle with the past but also became an ominous foreshadowing of the future."[16]

Wild men or savages—usually depicted carrying staves or clubs, living beyond the bounds of civilization without shelter or fire, lacking feelings and souls—were then a metaphor for man without God.[26] Common superstition held that long-haired wild men, known as lutins, who danced to firelight either to conjure demons or as part of fertility rituals, lived in mountainous areas such as the Pyrenees. In some village charivaris at harvest or planting time dancers dressed as wild men, to represent demons, were ceremonially captured and then an effigy of them was symbolically burnt to appease evil spirits. The church, however, considered these rituals pagan and demonic.[27][note 4]

Veenstra explains that it was believed that by dressing as wild men, villagers ritualistically "conjured demons by imitating them"—although at that period penitentials forbade a belief in wild men or an imitation of them, such as the costumed dance at Isabeau's event. In folkloric rituals the "burning did not happen literally but in effigie", he writes, "contrary to the Bal des Ardents where the seasonal fertility rite had watered down to courtly entertainment, but where burning had been promoted to a dreadful reality." A 15th-century chronicle describes the Bal des Ardents as una corea procurance demone ("a dance to ward off the devil").[28]

Because remarriage was often thought to be a sacrilege—common belief was that the sacrament of marriage extended beyond death—it was censured by the community. Thus the purpose of the Bal des Ardents was twofold: to entertain the court and to humiliate and rebuke Isabeau's lady-in-waiting—in an inherently pagan manner, which the Monk of St Denis seemed to dislike.[27] A ritual burning on the wedding night of a woman who was remarrying had Christian origins as well, according to Veenstra. The Book of Tobit partly concerns a woman who had seven husbands murdered by the demon Asmodeus; she is eventually freed of the demon by the burning of the heart and liver of a fish.[27][29]

The event also may have served as a symbolic exorcism of Charles's mental illness at a time when magicians and sorcerers were commonly consulted by members of the court. In the early 15th century, ritual burning of evil, demonic, or Satanic forces was not uncommon as shown by Orléans's later persecution of the King's physician Jehan de Bar, who was burned to death after confessing, under torture, to practicing sorcery.[27]

Chronicles

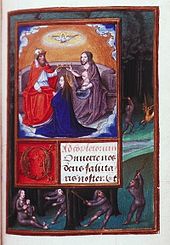

The death of four members of the nobility was sufficiently important to ensure that the event was recorded in contemporary chronicles, most notably by Froissart and the Monk of St Denis, and subsequently illustrated in a number of copies of illuminated manuscripts. While the two main chroniclers agree on essential points of the evening—the dancers were dressed as wild men, the king survived, one man fell into a vat, and four of the dancers died—there are discrepancies in the details. Froissart wrote that the dancers were chained together, which is not mentioned in the monk's account. Furthermore, the two chroniclers are at odds regarding the purpose of the dance. According to the historian Susan Crane, the monk describes the event as a wild charivari with the audience participating in the dance, whereas Froissart's description suggests a theatrical performance without audience participation.[30]

Froissart wrote about the event in Book IV of his Chronicles (covering the years 1389 to 1400), an account described by scholar Katerina Nara as full of "a sense of pessimism", as Froissart "did not approve of all he recorded".[31] Froissart blamed Orléans for the tragedy,[32] and the monk blamed the instigator, de Guisay, whose reputation for treating low-born servants like animals earned him such universal hatred that "the Nobles rejoiced at his agonizing death".[33]

The monk wrote of the event in the Histoire de Charles VI (History of Charles VI), covering about 25 years of Charles' reign.[34] He seemed to disapprove[note 5] on the grounds that the event broke social mores and the king's conduct was unbecoming, whereas Froissart described it as a celebratory event.[30]

Scholars are unsure whether either chronicler was present that evening. According to Crane, Froissart wrote of the event about five years later, and the monk about ten. Veenstra speculates that the monk may have been an eyewitness (as he was for much of Charles' reign) and that his account is the more accurate of the two.

The Froissart manuscript dating from between 1470 and 1472 from the

Notes and references

- ^ Sources vary whether the event was a masquerade or a masque.

- Jeanne of Bourbon. See Tuchman (1978), 367

- ^ The Monk of St Denis claimed the woman had been widowed three times, making it her fourth marriage. See Veenstra, 90

- Thuringenin Germany a ritual was performed in which a pfingstl—a leaf- and moss-clad villager representing a wild man—was ceremonially hunted and killed. Chambers (1996 ed.), 183–185

- ^ The Monk described the event as "contrary to all decency". See Tuchman (1978), 504

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Tuchman (1979), 503–505

- ^ a b c Veenstra (1997), 89–91

- ^ a b Tuchman (1978), 503

- ^ a b Tuchman (1978), 367

- ^ qtd. in Knecht (2007), 42

- ^ a b c Knecht (2007), 42–47

- ^ a b c d Tuchman (1978), 496–499

- ^ qtd. in Tuchman (1978), 498

- ^ a b Henneman (1996), 173–175

- ^ Seward (1987), 143

- ^ qtd. in Seward (1987), 144

- ^ Gibbons (1996), 57–59

- ^ Tuchman (1978), p502

- ^ qtd. in Tuchman (1978), 503

- ^ Tuchman (1978), 504

- ^ a b c Veenstra (1997), 91

- ^ qtd. in MacKay (2011), 167

- ^ Stock (2004) 159–160

- ^ Heckscher, 241

- ^ Tuchman (1978), 380

- ^ qtd. in Nara (2002), 237

- ^ Veenstra (1997), 60, 91, 95

- ^ Wagner (2006), 88; Tuchman (1978), 515–516

- ^ Tuchman (1978), 516

- ^ Tuchman (1978), 516, 537–538

- ^ Centerwell (1997), 27–28

- ^ a b c d Veenstra (1997), 92–94

- ^ Veenstra (1997), 94

- ^ Veenstra (1997), 67

- ^ a b c Crane (2002), 155–159

- ^ qtd. in Nara (2002), 230

- ^ Nara (2002), 237

- ^ Crane (2002), 157

- ^ Guenée, Bernard. (1994). "Documents insérés et documents abrégés dans la Chronique du religieux de Saint- Denis". Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. Vol. 152, No. 2, 375–428. Retrieved April 18, 2012.

- ^ a b "Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts" Archived 2020-08-01 at the Wayback Machine. British Library. Retrieved January 2, 2012

- ^ Veenstra (1997), 22

- ^ Adams (2010), 124

- ^ Curry (2000), 128; Famiglietti (1995), 505

- ^ "Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts" Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine. British Library. Retrieved March 3, 2012

- ^ "Illuminating the Renaissance". J. Paul Getty Trust. Retrieved January 2, 2012

- ISBN 978-2-600-00219-6

Works cited

- Adams, Tracy. (2010). The Life and Afterlife of Isabeau of Bavaria. Baltimore, MD: ISBN 978-0-8018-9625-5

- Centerwell, Brandon. (1997). "The Name of the Green Man". Folklore. Vol. 108. 25–33

- Chamber, E.R. (1996 ed.) The Medieval Stage. Mineola, New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-29229-8

- Crane, Susan. (2002). The Performance of Self: Ritual, Clothing and Identity During the Hundred Years War. Philadelphia: ISBN 978-0-8122-1806-0

- Curry, Anne. (2000). The Battle of Agincourt: Sources and Interpretations. Rochester, NY: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-802-0

- Famiglietti, Richard C. (1995). "Juvenal Des Ursins". in Kibler, William (ed). Medieval France: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland. ISBN 978-0-8240-4444-2

- Gibbons, Rachel. (1996). "Isabeau of Bavaria, Queen of France (1385–1422): The Creation of an Historical Villainess". The Royal Historical Society, Vol. 6. 51–73

- Heckscher, William. (1953). Review of Wild Men in the Middle Ages: A Study in Art, Sentiment, and Demonology by Richard Bernheimer. The Art Bulletin. Vol. 35, No. 3. 241–243

- Henneman, John Bell. (1996). Olivier de Clisson and Political Society in France under Charles V and Charles VI. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3353-7

- Knecht, Robert. (2007). The Valois: Kings of France 1328–1589. London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 978-1-85285-522-2

- MacKay, Ellen. (2011). Persecution, Plague, and Fire. Chicago: ISBN 978-0-226-50019-5

- Nara, Katerina. (2002). "Representations of Female Characters in Jean Froissarts Chroniques". in Kooper, Erik (ed.). The Medieval Chronicle VI. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-2674-2

- Seward, Desmond. (1978). The Hundred Years War: The English in France 1337–1453. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-17377-0

- Stock, Lorraine Kochanske. (2004). Review of The Performance of Self: Ritual, Clothing, and Identity during the Hundred Years War by Susan Crane. Speculum. Vol. 79, No. 1. 158–161

- Tuchman, Barbara. (1978). A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century. New York: Ballantine. ISBN 978-0-345-34957-6

- Veenstra, Jan R. and Laurens Pignon. (1997). Magic and Divination at the Courts of Burgundy and France. New York: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10925-4

- Wagner, John. (2006). Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years' War. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32736-0