Balak (parashah)

Balak (בָּלָק—

The name "Balak" means "devastator",[5] "empty",[6] or "wasting".[7] The name apparently derives from the rarely used Hebrew verb (balak), "waste or lay waste."[8]

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot.[9]

First reading—Numbers 22:2–12

In the first reading, Balak son of Zippor, king of Moab, grew alarmed at the

Second reading—Numbers 22:13–20

In the second reading, in the morning, Balaam asked Balak's dignitaries to leave, as God would not let him go with them, and they left and reported Balaam's answer to Balak.[14] Then Balak sent more numerous and distinguished dignitaries, who offered Balaam rich rewards in return for damning the Israelites.[15] But Balaam replied: "Though Balak were to give me his house full of silver and gold, I could not do anything, big or little, contrary to the command of the Lord my God."[16] Nonetheless, Balaam invited the dignitaries to stay overnight to let Balaam find out what else God might say to him, and that night God told Balaam: "If these men have come to invite you, you may go with them."[17]

Third reading—Numbers 22:21–38

In the third reading, in the morning, Balaam saddled his

Fourth reading—Numbers 22:39–23:12

In the fourth reading, Balaam and Balak went together to Kiriath-huzoth, where Balak sacrificed oxen and sheep, and they ate.[30] In the morning, Balak took Balaam up to Bamoth-Baal, overlooking the Israelites.[31] Balaam had Balak build seven altars, and they offered up a bull and a ram on each altar.[32] Then Balaam asked Balak to wait while Balaam went off alone to see if God would grant him a manifestation.[33] God appeared to Balaam and told him what to say.[34] Balaam returned and said: "How can I damn whom God has not damned, how doom when the Lord has not doomed? . . . Who can count the dust of Jacob, number the dust-cloud of Israel? May I die the death of the upright, may my fate be like theirs!"[35] Balak complained that he had brought Balaam to damn the Israelites, but instead Balaam blessed them.[36] Balaam replied that he could only repeat what God put in his mouth.[37]

Fifth reading—Numbers 23:13–26

In the fifth reading, Balak took Balaam to the summit of Pisgah, once offered a bull and a ram on each of seven altars, and once again Balaam asked Balak to wait while Balaam went off alone to seek a manifestation, and once again God told him what to say.[38] Balaam returned and told Balak: "My message was to bless: When He blesses, I cannot reverse it. No harm is in sight for Jacob, no woe in view for Israel. The Lord their God is with them."[39] Then Balak told Balaam at least not to bless them, but Balaam replied that he had to do whatever God directed.[40]

Sixth reading—Numbers 23:27–24:13

In the sixth reading, Balak took Balaam to the peak of Peor, and once offered a bull and a ram on each of seven altars.[41] Balaam, seeing that it pleased God to bless Israel, immediately turned to the Israelites and blessed them: "How fair are your tents, O Jacob, your dwellings, O Israel! . . . They shall devour enemy nations, crush their bones, and smash their arrows. . . . Blessed are they who bless you, accursed they who curse you!"[42] Enraged, Balak complained and dismissed Balaam.[43]

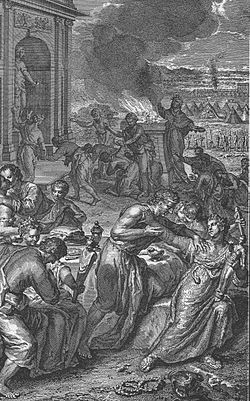

Seventh reading—Numbers 24:14–25:9

In the seventh reading, Balaam replied once again that he could not do contrary to God's command, and blessed Israelites once again, saying: "A

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to a different schedule.[50]

In inner-Biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[51]

Numbers chapter 22

In Micah 6:5, the prophet asked Israel to recall that Balak consulted Balaam and Balaam had advised him.

The only time in the Bible that Balak is not mentioned in direct conjunction with Balaam is in Judges 11:25.

Numbers chapter 23

Balaam's request in Numbers 23:10 to share Israel's fate fulfills God's blessing to Abraham in Genesis 12:3 that "all the families of the earth shall bless themselves by you," God's blessing to Abraham in Genesis 22:18 that "All the nations of the earth shall bless themselves by your descendants," and God's blessing to Jacob in Genesis 28:14 that "All the families of the earth shall bless themselves by you and your descendants."[52]

Numbers chapter 24

Balaam's observation that Israel was "encamped according to its tribes" (Numbers 24:2) shows that the leaders and people remained faithful to the tribe-based camp pattern which God had instructed Moses and Aaron to adopt in Numbers 2:1-14.

| North | ||||||

| Asher | DAN | Naphtali | ||||

| Benjamin | Merari | Issachar | ||||

| West | EPHRAIM | Gershon | THE TABERNACLE | Priests | JUDAH | East |

| Manasseh | Kohath | Zebulun | ||||

| Gad | REUBEN | Simeon | ||||

| South |

Psalm 1:3 interprets the words "cedars beside the waters" in Balaam's blessing in Numbers 24:6. According to Psalm 1:3, "a tree planted by streams of water" is one "that brings forth its fruit in its season, and whose leaf does not wither."

Numbers 24:17–18 prophesied, "A star rises from Jacob, a scepter comes forth from Israel . . . Edom becomes a possession, yea, Seir a possession of its enemies; but Israel is triumphant." Similarly, in Amos 9:11–12, the 8th century BCE prophet Amos announced a prophecy of God: "In that day, I will set up again the fallen booth of David: I will mend its breaches and set up its ruins anew. I will build it firm as in the days of old, so that they shall possess the rest of Edom."

Numbers chapter 25

Tikva Frymer-Kensky called the Bible's six memories of the Baal-Peor incident in Numbers 25:1–13, Numbers 31:15–16, Deuteronomy 4:3–4, Joshua 22:16–18, Ezekiel 20:21–26, and Psalm 106:28–31 a testimony to its traumatic nature and to its prominence in Israel's memory.[53]

In the retelling of Deuteronomy 4:3–4, God destroyed all the men who followed the Baal of Peor, but kept alive to the day of Moses's address everyone who cleaved to God. Frymer-Kensky concluded that Deuteronomy stresses the moral lesson: Very simply, the guilty perished, and those who were alive to hear Moses were innocent survivors who could avoid destruction by staying fast to God.[53]

In Joshua 22:16–18, Phinehas and ten princes of Israelite Tribes questioned the Reubenites’ and Manassites’ later building an altar across the Jordan, recalling that the Israelites had not cleansed themselves to that day of the iniquity of Peor, even though a plague had come upon the congregation at the time. Frymer-Kensky noted that the book of Joshua emphasizes the collective nature of sin and punishment, that the transgression of the Israelites at Peor still hung over them, and that any sin of the Reubenites and Manassites would bring down punishment on all Israel.[53]

In Ezekiel 20:21–26, God recalled Israel's rebellion and God's resolve to pour out God's fury on them in the wilderness. God held back then for the sake of God's Name, but swore that God would scatter them among the nations, because they looked with longing at idols. Frymer-Kensky called Ezekiel's memory the most catastrophic: Because the Israelites rebelled in the Baal-Peor incident, God vowed that they would ultimately lose the Land that they had not yet even entered. Even after the exile to Babylon, the incident loomed large in Israel's memory.[54]

Psalm 106:28–31 reports that the Israelites attached themselves to Baal Peor and ate sacrifices offered to the dead, provoking God's anger and a plague. Psalm 106:30–31 reports that Phinehas stepped forward and intervened, the plague ceased, and it was reckoned to his merit forever. Frymer-Kensky noted that the Psalm 106:28–31, like Numbers 25:1–13, includes a savior, a salvation, and an explanation of the monopoly of the priesthood by the descendants of Phineas.[54] Michael Fishbane wrote that in retelling the story, the Psalmist notably omitted the explicit account of Phinehas's violent lancing of the offenders and substituted an account of the deed that could be read as nonviolent.[55]

Numbers 31:16 reports that Balaam counseled the Israelites to break faith with God in the sin of Baal-Peor.

Joshua 13:22 states that the Israelites killed Balaam “the soothsayer” during war.

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[56]

Numbers chapter 22

A Baraita taught that Moses wrote the Torah, the portion of Balaam, and the book of Job.[57]

A Midrash explained that the Torah records Balaam's story to make known that because the nonbeliever prophet Balaam did what he did, God removed prophecy and the Holy Spirit from nonbelievers. The Midrash taught that God originally wished to deprive nonbelievers of the opportunity to argue that God had estranged them. So in an application of the principle of Deuteronomy 32:4, "The Rock, His work is perfect; for all His ways are Justice," God raised up kings, sages, and prophets for both Israel and nonbelievers alike. Just as God raised up Moses for Israel, God raised up Balaam for the nonbelievers. But whereas the prophets of Israel cautioned Israel against transgressions, as in Ezekiel 3:17, Balaam sought to breach the moral order by encouraging the sin of Baal-Peor in Numbers 25:1–13. And while the prophets of Israel retained compassion towards both Israel and nonbelievers alike, as reflected in Jeremiah 48:36 and Ezekiel 27:2, Balaam sought to uproot the whole nation of Israel for no crime. Thus God removed prophecy from nonbelievers.[58]

Reading Deuteronomy 2:9, "And the Lord spoke to me, ‘Distress not the Moabites, neither contend with them in battle,’" Ulla argued that it certainly could not have entered the mind of Moses to wage war without God's authorization. So we must deduce that Moses on his own reasoned that if in the case of the Midianites who came only to assist the Moabites (in Numbers 22:4), God commanded (in Numbers 25:17), "Vex the Midianites and smite them," in the case of the Moabites themselves, the same injunction should apply even more strongly. But God told Moses that his idea was incorrect. For God was to bring two doves forth from the Moabites and the Ammonites—Ruth the Moabitess and Naamah the Ammonitess.[59]

Classical Rabbinic interpretation viewed Balaam unfavorably. The Mishnah taught that Balaam was one of four commoners who have no portion in the

Similarly, the Mishnah taught that anyone who has an evil eye, a haughty spirit, and an over-ambitious soul is a disciple of Balaam the wicked, and is destined for Gehinnom and descent into the pit of destruction. The Mishnah taught that Psalm 55:24 speaks of the disciples of Balaam when it says, "You, o God, will bring them down to the nethermost pit; men of blood and deceit shall not live out half their days.[62]

Reading the description of Joshua 13:22, "Balaam also the son of Beor, the soothsayer," the Gemara asked why Joshua 13:22 describes Balaam merely as a soothsayer when he was also a prophet. Rabbi Joḥanan taught that at first, Balaam was a prophet, but at the end, he was merely a soothsayer.

Interpreting the words, "And the elders of Moab and the elders of Midian departed," in Numbers 22:7 a Tanna taught that there never was peace between Midian and Moab, comparing them to two dogs in a kernel that always fought each other. Then a wolf attacked one, and the other concluded that if he did not help the first, then the wolf would attack the second tomorrow. So they joined to fight the wolf. And Rav Papa likened the cooperation of Moab and Midian to the saying: "The weasel and cat had a feast on the fat of the luckless."[61]

Noting that Numbers 22:8 makes no mention of the princes of Midian, the Gemara deduced that they despaired as soon as Balaam told them (in Numbers 22:8) that he would listen to God's instructions, for they reasoned that God would not curse Israel any more than a father would hate his son.[61]

Noting that in Numbers 22:12 God told Balaam, "You shall not go with them," yet in Numbers 22:20, after Balaam impudently asked God a second time, God told Balaam, "Rise up and go with them," Rav Nachman concluded that impudence, even in the face of Heaven, sometimes brings results.[61]

A

A Tanna taught in the name of Rabbi Simeon ben Eleazar that intense love and hate can cause one to disregard the perquisites of one's social position. The Tanna deduced that love may do so from Abraham, for Genesis 22:3 reports that "Abraham rose early in the morning, and saddled his donkey," rather than allow his servant to do so. Similarly, the Tanna deduced that hate may do so from Balaam, for Numbers 22:21 reports that "Balaam rose up in the morning, and saddled his donkey," rather than allow his servant to do so.[65]

Reading Numbers 22:23, a Midrash remarked on the irony that the villain Balaam was going to curse an entire nation that had not sinned against him, yet he had to smite his donkey to prevent it from going into a field.[66]

The Mishnah taught that the mouth of the donkey that miraculously spoke to Balaam in Numbers 22:28–30 was one of ten things that God created on the eve of the first Sabbath at twilight.[67]

Expanding on Numbers 22:30, the Gemara reported a conversation among Balak's emissaries, Balaam, and Balaam's donkey. Balak's emissaries asked Balaam, "Why didn’t you ride your horse?" Balaam replied, "I have put it out to pasture." But Balaam's donkey asked Balaam (in the words of Numbers 22:30), "Am I not your donkey?" Balaam replied, "Merely for carrying loads." Balaam's donkey said (in the words of Numbers 22:30), "Upon which you have ridden." Balaam replied, "That was only by chance." Balaam's donkey insisted (in the words of Numbers 22:30), "Ever since I was yours until this day."[65]

The school of Rabbi Natan taught that the Torah contains an abbreviation in Numbers 22:32, “And the angel of the Lord said to him: Why did you hit your donkey these three times? Behold I have come out as an adversary because your way is contrary (יָרַט, yarat) against me.” The school of Rabbi Natan interpreted the word יָרַט, yarat, as an abbreviation for, “The donkey feared (יראה, yare’ah), it saw (ראתה, ra’atah), and it turned aside (נטתה, natetah).[68]

Numbers chapter 23

Rabbi Joḥanan deduced from the words "and he walked haltingly" in Numbers 23:3 that Balaam was disabled in one leg.[61]

Rabbi Joḥanan interpreted the words "And the Lord put a word (or 'a thing') in Balaam's mouth" in Numbers 23:5 to indicate that God put a hook in Balaam's mouth, playing Balaam like a fish.[65] Similarly, a Midrash taught that God controlled Balaam's mouth as a person who puts a bit into the mouth of a beast and makes it go in the direction the person pleases.[69]

Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani interpreted the words "that the Lord your God shall keep for you" in Deuteronomy 7:12, teaching that all the good that Israel enjoys in this world results from the blessings with which Balaam blessed Israel, but the blessings with which the Patriarchs blessed Israel are reserved for the time to come, as signified by the words, "that the Lord your God shall keep for you."[70]

The Gemara interpreted the words "knowing the mind of the most High" in Numbers 24:16 to mean that Balaam knew how to tell the exact moment when God was angry. The Gemara taught that this was related to what

The

The Gemara interpreted Balaam's words, "Let me die the death of the righteous," in Numbers 23:10 to foretell that he would not enter the World To Come. The Gemara interpreted those words to mean that if Balaam died a natural death like the righteous, then his end would be like that of the Jewish people, but if he died a violent death, then he would go to the same fate as the wicked.[61]

Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba taught in the name of Rabbi Joḥanan that when in Numbers 23:10, Balaam said, "Let me die the death of the righteous," he sought the death of the Patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, who were called righteous.[73]

A Midrash taught that God concealed Balaam's fate from him until he had already sealed his fate. When he then saw his future, he began to pray for his soul in Numbers 23:10, "Let my soul die the death of the righteous."[74]

Reading Numbers 23:24 and 24:9 (and other verses), Rabbi Joḥanan noted that the lion has six names[75]—אֲרִי, ari in Numbers 23:24 and 24:9;[76] כְּפִיר, kefir;[77] לָבִיא, lavi in Numbers 23:24 and 24:9;[78] לַיִשׁ, laish;[79] שַׁחַל, shachal;[80] and שָׁחַץ, shachatz.[81]

The Tosefta read Numbers 23:24, "as a lion . . . he shall not lie down until he eats of the prey, and drinks the blood of the slain," to support the categorization of blood as a "drink" for the purpose of Sabbath limitations.[82]

Numbers chapter 24

Rabbi Joḥanan interpreted Numbers 24:2 to support the rule of Mishnah Bava Batra 3:7 that a person should not construct a house so that its doorway opens directly opposite another doorway across a courtyard. Rabbi Joḥanan taught that the words of Numbers 24:2, "And Balaam lifted up his eyes and he saw Israel dwelling according to their tribes," indicate that Balaam saw that the doors of their tents did not exactly face each other (and that the Israelites thus respected each other's privacy). So Balaam concluded that the Israelites were worthy to have the Divine Presence rest upon them (and he spoke his blessing in Numbers 24:5 of the tents of Jacob).[83]

The Gemara deduced from the words "the man whose eye is open" in Numbers 24:3, which refer to only a single open eye, that Balaam was blind in one eye.[61]

Rabbi Abbahu explained how Balaam became blind in one eye. Rabbi Abbahu interpreted the words of Balaam's blessing in Numbers 23:10, "Who has counted the dust of Jacob, or numbered the stock of Israel?" to teach that God counts the cohabitations of Israel, awaiting the appearance of the drop from which a righteous person might grow. Balaam questioned how God Who is pure and holy and Whose ministers are pure and holy could look upon such a thing. Immediately, Balaam's eye became blind, as attested in Numbers 24:3 (with its reference to a single open eye).[84]

Rabbi Joḥanan taught that one may learn Balaam's intentions from the blessings of Numbers 24:5–6, for God reversed every intended curse into a blessing. Thus Balaam wished to curse the Israelites to have no synagogues or school-houses, for Numbers 24:5, "How goodly are your tents, O Jacob," refers to synagogues and school-houses. Balaam wished that the Shechinah should not rest upon the Israelites, for in Numbers 24:5, "and your tabernacles, O Israel," the Tabernacle symbolizes the Divine Presence. Balaam wished that the Israelites' kingdom should not endure, for Numbers 24:6, "As the valleys are they spread forth," symbolizes the passing of time. Balaam wished that the Israelites might have no olive trees and vineyards, for in Numbers 24:6, he said, "as gardens by the river's side." Balaam wished that the Israelites' smell might not be fragrant, for in Numbers 24:6, he said, "as aloes planted of the Lord." Balaam wished that the Israelites' kings might not be tall, for in Numbers 24:6, he said, "and as cedar trees beside the waters." Balaam wished that the Israelites might not have a king who was the son of a king (and thus that they would have unrest and civil war), for in Numbers 24:6, he said, "He shall pour the water out of his buckets," signifying that one king would descend from another. Balaam wished that the Israelites' kingdom might not rule over other nations, for in Numbers 24:6, he said, "and his seed shall be in many waters." Balaam wished that the Israelites' kingdom might not be strong, for in Numbers 24:6, he said, "and his king shall be higher than Agag. Balaam wished that the Israelites’ kingdom might not be awe-inspiring, for in Numbers 24:6, he said, "and his kingdom shall be exalted. Rabbi Abba bar Kahana said that all of Balaam's curses, which God turned into blessings, reverted to curses (and Balaam's intention was eventually fulfilled), except the synagogues and schoolhouses, for Deuteronomy 23:6 says, "But the Lord your God turned the curse into a blessing for you, because the Lord your God loved you," using the singular "curse," and not the plural "curses" (so that God turned only the first intended curse permanently into a blessing, namely that concerning synagogues and school-houses, which are destined never to disappear from Israel).[65]

A Midrash told that when the Israelites asked Balaam when salvation would come, Balaam replied in the words of Numbers 24:17, "I see him (the Messiah), but not now; I behold him, but not near." God asked the Israelites whether they had lost their sense, for they should have known that Balaam would eventually descend to Gehinnom, and therefore did not wish God's salvation to come. God counseled the Israelites to be like Jacob, who said in Genesis 49:18, "I wait for Your salvation, O Lord." The Midrash taught that God counseled the Israelites to wait for salvation, which is at hand, as Isaiah 54:1 says, "For My salvation is near to come."[85]

Numbers chapter 25

Rabbi Joḥanan taught that wherever Scripture uses the term "And he abode" (וַיֵּשֶׁב, vayeishev), as it does in Numbers 25:1, it presages trouble. Thus, in Numbers 25:1, "And Israel abode in Shittim" is followed by "and the people began to commit whoredom with the daughters of Moab." In Genesis 37:1, "And Jacob dwelt in the land where his father was a stranger, in the land of Canaan," is followed by Genesis 37:3, "and Joseph brought to his father their evil report." In Genesis 47:27, "And Israel dwelt in the land of Egypt, in the country of Goshen," is followed by Genesis 47:29, "And the time drew near that Israel must die." In 1 Kings 5:5, "And Judah and Israel dwelt safely, every man under his vine and under his fig tree," is followed by 1 Kings 11:14, "And the Lord stirred up an adversary unto Solomon, Hadad the Edomite; he was the king's seed in Edom."[86]

A Midrash taught that God heals with the very thing with which God wounds. Thus, Israel sinned in Shittim (so called because of its many acacia trees), as Numbers 25:1 says, "And Israel abode in Shittim, and the people began to commit harlotry with the daughters of Moab" (and also worshipped the Baal of Peor). But it was also through Shittim wood, or acacia-wood, that God healed the Israelites, for as Exodus 37:1 reports, "Bezalel made the Ark of acacia-wood."[87]

Rabbi Judah taught that the words of Job 21:16, "The counsel of the wicked is far from me," refer to the counsel of Balaam, the wicked, who advised Midian, resulting in the death of 24,000 Israelite men. Rabbi Judah recounted that Balaam advised the Midianites that they would not be able to prevail over the Israelites unless the Israelites had sinned before God. So the Midianites made booths outside the Israelite camp and sold all kinds of merchandise. The young Israelite men went beyond the Israelite camp and saw the young Midianite women, who had painted their eyes like harlots, and they took wives from among them, and went astray after them, as Numbers 25:1 says, "And the people began to commit whoredom with the daughters of Moab."[88]

Rabbi Hama son of Rabbi Hanina taught that Moses was buried near Beth-Peor to atone for the incident at Beth-Peor in Numbers 25.[89]

The Rabbis taught that if a witness accused someone of worshipping an idol, the judges would ask, among other questions, whether the accused worshiped Peor (as Numbers 25:3 reports that the Israelites did).[90]

Rabbah bar bar Hana said in Rabbi Joḥanan's name that had Zimri withdrawn from Cozbi and Phinehas still killed him, Phinehas would have been liable to execution for murder, and had Zimri killed Phinehas in self-defense, he would not have been liable to execution for murder, as Phinehas was a pursuer seeking to take Zimri's life.[91]

The Gemara related what took place after, as Numbers 25:5 reports, "Moses said to the judges of Israel: ‘Slay everyone his men who have joined themselves to the Baal of Peor.’" The tribe of Simeon went to Zimri complaining that capital punishment was being meted out while he sat silently. So Zimri assembled 24,000 Israelites and went to Cozbi and demanded that she surrender herself to him. She replied that she was a king's daughter and her father had instructed her not to submit to any but to the greatest of men. Zimri replied that he was the prince of a tribe and that his tribe was greater than that of Moses, for

Interpreting the words, "And Phineas, the son of Eleazar, the son of Aaron the priest, saw it," in Numbers 25:7, the Gemara asked what Phineas saw.

Reading the words of Numbers 25:7, "When Phinehas the son of Eleazar, son of Aaron the priest, saw," the Jerusalem Talmud asked what he saw. The Jerusalem Talmud answered that he saw the incident and remembered the law that zealots may beat up one who has sexual relations with an Aramean woman. But the Jerusalem Talmud reported that it was taught that this was not with the approval of sages. Rabbi Judah bar Pazzi taught that the sages wanted to excommunicate Phinehas, but the Holy Spirit rested upon him and stated the words of Numbers 25:13, "And it shall be to him, and to his descendants after him, the covenant of a perpetual priesthood, because he was jealous for his God, and made atonement for the people of Israel."[92]

The Gemara taught that Phineas then removed the point of the spear and hid it in his clothes, and went along leaning upon the shaft of the spear as a walking stick. When he reached the tribe of Simeon, he asked why the tribe of Levi should not have the moral standards of the tribe of Simeon. Thereupon the Simeonites allowed him to pass through, saying that he had come to satisfy his lust. The Simeonites concluded that even the abstainers had then declared cohabiting wit Midianite women permissible.[93]

Rabbi Joḥanan taught that Phinehas was able to accomplish his act of zealotry only because God performed six miracles: First, upon hearing Phinehas's warning, Zimri should have withdrawn from Cozbi and ended his transgression, but he did not. Second, Zimri should have cried out for help from his fellow Simeonites, but he did not. Third, Phinheas was able to drive his spear exactly through the sexual organs of Zimri and Cozbi as they were engaged in the act. Fourth, Zimri and Cozbi did not slip off the spear, but remained fixed so that others could witness their transgression. Fifth, an angel came and lifted up the lintel so that Phinheas could exit holding the spear. And sixth, an angel came and sowed destruction among the people, distracting the Simeonites from killing Phinheas.[94]

The interpreters of Scripture by symbol taught that the deeds of Phinehas explained why Deuteronomy 18:3 directed that the priests were to receive the foreleg, cheeks, and stomach of sacrifices. The foreleg represented the hand of Phinehas, as Numbers 25:7 reports that Phinehas "took a spear in his hand." The cheeks represent the prayer of Phinehas, as Psalm 106:30 reports, "Then Phinehas stood up and prayed, and so the plague was stayed." The stomach was to be taken in its literal sense, for Numbers 25:8 reports that Phinehas "thrust . . . the woman through her belly."[95]

Based on Numbers 25:8 and 11, the Mishnah listed the case of a man who had sexual relations with an Aramaean woman as one of three cases for which it was permissible for zealots to punish the offender on the spot.[96]

The Gemara asked whether the words in Exodus 6:25, "And

The Gemara told that the Hasmonean King Alexander Jannaeus advised his wife not to fear the Pharisees or the Sadducees, but to beware of pretenders who sought to appear like Pharisees, as they acted like the wicked Zimri but sought a reward like that of the righteous Phinehas.[99]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[100]

Numbers chapter 22

Noting that Numbers 22:23 reports that "the she-donkey saw" but Balaam did not see, Rashi explained that God permitted the animal to perceive more than the person, as a person possesses intelligence and would be driven insane by the sight of a harmful spirit.[101]

In the word "even" (גַּם, gam) in Numbers 22:33 (implying that the angel would also have killed Balaam), Abraham ibn Ezra found evidence for the proposition that the donkey died after she spoke.[102]

Numbers chapter 23

Rashi read Balaam's request in Numbers 23:10 to "die the death of the upright" to mean that Balaam sought to die among the Israelites.

Numbers chapter 25

Following the Mishnah[96] (see “In classical rabbinic interpretation” above), Maimonides acknowledged that based on Phinehas's slaying of Zimri, a zealot would be considered praiseworthy to strike a man who has sexual relations with a gentile woman in public, that is, in the presence of ten or more Jews. But Maimonides taught that the zealot could strike the fornicators only when they were actually engaged in the act, as was the case with Zimri, and if the transgressor ceased, he should not be slain, and if the zealot then killed the transgressor, the zealot could be executed as a murderer. Further, Maimonides taught that if the zealot came to ask permission from the court to kill the transgressor, the court should not instruct the zealot to do so, even if the zealot consulted the court during the act.[108]

Baḥya ibn Paquda taught that those who trust that God will favor them without performing good deeds are like those of whom the Talmud says that they act like Zimri and expect the reward of Pinchas.[109]

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Numbers chapter 22

Baruch Spinoza noted the similarity between Balak's description of Balaam in Numbers 22:6, "he whom you bless is blessed, and he whom you curse is cursed," and God's blessing of Abraham in Genesis 12:3 and deduced that Balaam also possessed the prophetic gift that God had given Abraham. Spinoza concluded that other nations, like the Jews, thus had their prophets who prophesied to them. And Spinoza concluded that Jews, apart from their social organization and government, possessed no gift of God above other peoples, and that there was no difference between Jews and non-Jews.[110]

Robert Alter observed that the Balaam narrative builds on repeated key words and actions, but repeats only certain phrases and dialogue verbatim. Alter pointed out that in Hebrew, the first word of the story in Numbers 22:2 is the verb "to see" (וַיַּרְא), which then becomes (with some synonyms) the main Leitwort in the tale about the nature of prophecy or vision. In Numbers 22:2, Balak saw what Israel did to the Amorites; in a vision in Numbers 23:9, Balaam saw Israel below him; in his last prophecy in Numbers 24:17, Balaam foresaw Israel's future. Balaam prefaced his last two prophecies with an affirmation in Numbers 24:3–4 of his powers as a seer: "utterance of the man open-eyed, . . . who the vision of Shaddai beholds, prostrate with eyes unveiled." Alter noted that all this "hullabaloo of visionary practice" stands in ironic contrast to Balaam's blindness to the angel his donkey could plainly see, until in Numbers 22:31, God chose to "unveil his eyes." Alter concluded that the story insists that God is the exclusive source of vision. Alter also noted reiterated phrase-motifs bearing on blessings and curses. In Numbers 22:6, Balak sent for Balaam to curse Israel believing that "Whom you bless is blessed and whom you curse is cursed." In Numbers 22:12, God set matters straight using the same two verb-stems: "You shall not curse the people, for it is blessed." In Numbers 23:7–8, Balaam concluded: "From Aram did Balak lead me . . . : ‘Go, curse me Jacob, and go, doom Israel.’ What can I curse that El has not cursed, and what can I doom that the Lord has not doomed?" Alter observed that Balaam was a poet as well as a seer, and taught that the story ultimately addresses whether language confers or confirms blessings and curses, and what the source of language's power is.[111]

Nili Sacher Fox noted that Balaam’s talking donkey, whom Numbers 22:21–34 portrays as wiser than Balaam, is a jenny, a female donkey, perhaps reminiscent of the biblical personification of wisdom (חָכְמָה, chochmah) as female in, for example, Proverbs 1:20.[112]

Diane Aronson Cohen wrote that the story of Balaam and his donkey in Numbers 22:21–34 provides an important model of an abuser venting misdirected anger in verbal abuse and physical violence. Cohen noted that the recipient of the abuse finally decided that she had had enough and stopped the abuse by speaking up. Cohen taught that we learn from the donkey that if we are on the receiving end of abuse, we have an obligation to speak out against our abuser.[113]

Numbers chapter 23

Nehama Leibowitz contrasted God’s call of Israel’s prophets in Jeremiah 1:4, Ezekiel 1:3, Hosea 1:1, and Joel 1:1 with Balaam’s preliminaries to communion with God in Numbers 22:1–3 and 23:14–16. Leibowitz noted that Israel’s prophets did not run after prophecy, while Balaam hankered after prophecy, striving through magical means to force such power down from Heaven. Leibowitz marked a change in Balaam’s third address, however, when Numbers 24:2 reports, “the spirit of God came upon him.”[114]

Numbers chapter 24

Leibowitz contrasted how Israel's prophets continually emphasize the Divine authority for their messages, often using the phrase, “says the Lord,” while Balaam prefaced his two later utterances in Numbers 24:3–16 with the introduction “The saying of Balaam the son of Beor, and the saying of the man whose eye is opened.”[115]

Numbers chapter 25

Dennis Olson noted parallels between the incident at Baal-Peor in Numbers 25:1–13 and the incident of the Golden Calf in Exodus 32, as each story contrasts God's working to ensure a relationship with Israel while Israel rebels.[116] Olson noted these similarities: (1) In both stories, the people worship and make sacrifices to another god.[117] (2) Both stories involve foreigners, in the Egyptians’ gold for the calf[118] and the women of Moab and Midian.[119] (3) In the aftermath of the Golden Calf story in Exodus 34:15–16, God commands the Israelites to avoid what happens in Numbers 25: making a covenant with the inhabitants, eating their sacrifices, and taking wives from among them who would make the Israelites’ sons bow to their gods. Numbers 25 displays this intermingling of sex and the worship of foreign gods, using the same Hebrew word, zanah, in Numbers 25:1. (4) The Levites kill 3,000 of those guilty of worshiping the Golden Calf,[120] and the Israelite leaders are instructed to kill the people who had yoked themselves to the Baal of Peor.[121] (5) Because of their obedience in carrying out God's punishment on the idolaters, the Levites are ordained for the service of God,[122] and in Numbers 25, the priest Phinehas executes God's punishment on the sinners, and a special covenant of perpetual priesthood is established with him.[123] (6) After the Golden Calf incident, Moses “makes atonement” for Israel,[124] and in the Baal Peor episode, Phinehas “makes atonement” for Israel.[125] (7) A plague is sent as punishment in both incidents.[126]

George Buchanan Gray wrote that the Israelite men's participation in the sacrificial feasts followed their intimacy with the women, who then naturally invited their paramours to their feasts, which, according to custom, were sacrificial occasions. Gray considered that it would have been in accord with the sentiment of early Israelites to worship the Moabite god on his own territory.[127] Similarly, Frymer-Kensky wrote that the cataclysm began with a dinner invitation from the Moabite women, who perhaps wanted to be friendly with the people whom Balaam had tried, but failed, to curse.[128]

Noting that the story of Baal Peor in Numbers 25 shifts abruptly from Moabite women to the Midianite princess Cozbi, Frymer-Kensky suggested that the story may originally have been about Midianite women, whom Moses held responsible in Numbers 31:15–16. Frymer-Kensky suggested that "Moabite women" appear in Numbers 25 as an artistic device to create a symmetrical antithesis to the positive image of Ruth.[129]

Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin (the Netziv) wrote that in Numbers 25:12, in reward for turning away God's wrath, God blessed Phinehas with the attribute of peace, so that he would not be quick-tempered or angry. Since the nature of Phinehas's act, killing with his own hands, left his heart filled with intense emotional unrest, God provided a means to soothe him so that he could cope with his situation and find peace and tranquility.[130]

Tamara Cohn Eskenazi found the opening scene of Numbers 25 disturbing for a number of reasons: (1) because the new generation of Israelites fell prey to idolatry within view of the Promised Land; (2) because God rewarded Phinehas for acting violently and without recourse to due process; and (3) because women receive disproportionate blame for the people's downfall. Eskenazi taught that God rewarded Phinehas, elevating him above other descendants of Aaron, because of Phinehas's swift and ruthless response to idolatry, unlike his grandfather Aaron, who collaborated with idolaters in the case of the Golden Calf. By demonstrating unflinching loyalty to God, Phinehas restored the stature of the priests as deserving mediators between Israel and God. Eskenazi noted that although God ordered death for all the ringleaders in Numbers 25:4, Phinehas satisfied God's demand for punishment by killing only two leaders, thereby causing less rather than more bloodshed.[131]

Commandments

According to Maimonides and the Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are no commandments in the parashah.[132]

Haftarah

The haftarah for the parashah is Micah 5:6–6:8. When parashah Balak is combined with parashah Chukat (as it is in 2026 and 2027), the haftarah remains the haftarah for Balak.[133]

Connection between the haftarah and the parashah

In the haftarah in Micah 6:5, Micah quotes God's admonition to the Israelites to recall the events of the parashah, to "remember now what Balak king of Moab devised, and what Balaam the son of Beor answered him." The verb that the haftarah uses for "answer" (עָנָה, ‘anah) in Micah 6:5 is a variation of the same verb that the parashah uses to describe Balaam's "answer" (וַיַּעַן, vaya‘an) to Balaak in the parashah in Numbers 22:18 and 23:12. And the first words of Balaam's blessing of Israel in Numbers 24:5, "how goodly" (מַה-טֹּבוּ,

The haftarah in classical rabbinic interpretation

The Gemara read the closing admonition of the haftarah, ""to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God," as one of several distillations of the principles underlying the Torah. Rabbi Simlai taught that God communicated 613 precepts to Moses. David reduced them to eleven principles, as Psalm 15 says, "Lord, who shall sojourn in Your Tabernacle? Who shall dwell in Your holy mountain?—He who [1] walks uprightly, and [2] works righteousness, and [3] speaks truth in his heart; who [4] has no slander upon his tongue, [5] nor does evil to his fellow, [6] nor takes up a reproach against his neighbor, [7] in whose eyes a vile person is despised, but [8] he honors them who fear the Lord, [9] he swears to his own hurt and changes not, [10] he puts not out his money on interest, [11] nor takes a bribe against the innocent." Isaiah reduced them to six principles, as Isaiah 33:15–16 says, "He who [1] walks righteously, and [2] speaks uprightly, [3] he who despises the gain of oppressions, [4] who shakes his hand from holding of bribes, [5] who stops his ear from hearing of blood, [6] and shuts his eyes from looking upon evil; he shall dwell on high." Micah reduced them to three principles, as Micah 6:8 says, "It has been told you, o man, what is good, and what the Lord requires of you: only [1] to do justly, and [2] to love mercy, and [3] to walk humbly before your God." The Gemara interpreted "to do justly" to mean maintaining justice; "to love mercy" to mean rendering every kind office, and "walking humbly before your God" to mean walking in funeral and bridal processions. And the Gemara concluded that if the Torah enjoins "walking humbly" in public matters, it is ever so much more requisite in matters that usually call for modesty. Returning to the commandments of the Torah, Isaiah reduced them to two principles, as Isaiah 56:1 says, "Thus says the Lord, [1] Keep justice and [2] do righteousness." Amos reduced them to one principle, as Amos 5:4 says, "For thus says the Lord to the house of Israel, ‘Seek Me and live.’" To this Rav Nahman bar Isaac demurred, saying that this might be taken as: Seek Me by observing the whole Torah and live. The Gemara concluded that Habakkuk based all the Torah's commandments on one principle, as Habakkuk 2:4 says, "But the righteous shall live by his faith."[134]

In the liturgy

Some Jews read about how the donkey opened its mouth to speak to Balaam in Numbers 22:28 and Balaam's three traits as they study Pirkei Avot chapter 5 on a Sabbath between Passover and Rosh Hashanah.[135]

The

Balaam's blessing of Israel in Numbers 24:5 constitutes the first line of the Ma Tovu prayer often said upon entering a synagogue or at the beginning of morning services. These words are the only prayer in the siddur attributed to a non-Jew.[137]

The Weekly Maqam

In

See also

- Islamic view of Balaam

Notes

- ^ Numbers 22:1–5.

- ^ Numbers 22:21–35.

- ^ "Torah Stats—Bemidbar". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

- ^ "Parashat Balak". Hebcal. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ^ Francis Brown, S.R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs, The New Brown-Driver-Briggs-Gesenius Hebrew and English Lexicon (Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1979), pages 118–19.

- ^ New Open Bible Study Bible Name List.

- ^ Alfred Jones, Jones' Dictionary of Old Testament Proper Names (Kregel Academic and Professional, 1990).

- ^ See Francis Brown, S.R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs, New Brown-Driver-Briggs-Gesenius Hebrew and English Lexicon, page 118 (Isaiah 24:1–3; Jeremiah 51:2).

- ^ See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Bamidbar/Numbers (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2007), pages 154–76.

- ^ Numbers 22:2–4.

- ^ Numbers 22:4–7.

- ^ Numbers 22:8.

- ^ Numbers 22:9–12.

- ^ Numbers 22:13–14.

- ^ Numbers 22:15–17.

- ^ Numbers 22:18.

- ^ Numbers 22:19–20.

- ^ Numbers 22:21–22.

- ^ Numbers 22:23.

- ^ Numbers 22:24.

- ^ Numbers 22:25.

- ^ Numbers 22:26–27.

- ^ Numbers 22:28–30.

- ^ Numbers 22:31.

- ^ Numbers 22:32–33.

- ^ Numbers 22:34.

- ^ Numbers 22:35.

- ^ Numbers 22:36–37.

- ^ Numbers 22:38.

- ^ Numbers 22:39–40.

- ^ Numbers 22:41.

- ^ Numbers 23:1–2.

- ^ Numbers 23:3.

- ^ Numbers 23:4–5.

- ^ Numbers 23:6–10.

- ^ Numbers 23:11.

- ^ Numbers 23:12.

- ^ Numbers 23:13–16.

- ^ Numbers 23:17–21.

- ^ Numbers 23:25–26.

- ^ Numbers 23:27–30.

- ^ Numbers 24:1–9.

- ^ Numbers 24:10–12.

- ^ Numbers 24:14–24.

- ^ Numbers 24:25.

- ^ Numbers 25:1–3.

- ^ Numbers 25:4–5.

- ^ Numbers 25:6–8.

- ^ Numbers 25:8–9.

- ^ See, e.g., Richard Eisenberg, "A Complete Triennial Cycle for Reading the Torah," in Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards/1986–1990 (New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2005), pages 383–418.

- ^ For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer, "Inner-biblical Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, The Jewish Study Bible, 2nd edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), pages 1835–41.

- ^ See Jacob Milgrom. The JPS Torah Commentary: Numbers: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, page 155. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1990.

- ^ a b c Tikva Frymer-Kensky, Reading the Women of the Bible (New York: Schocken Books, 2002), page 215.

- ^ a b Tikva Frymer-Kensky, Reading the Women of the Bible, page 216.

- ^ Michael Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), pages 397–99.

- ^ For more on classical rabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Yaakov Elman, "Classical Rabbinic Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, Jewish Study Bible, 2nd edition, pages 1859–78.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 14b.

- ^ Numbers Rabbah 20:1.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Bava Kamma 38a–b.

- ^ Mishnah Sanhedrin 10:2; Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 90a.

- ^ a b c d e f g Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 105a.

- ^ Mishnah Avot 5:19.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 106a.

- ^ Genesis Rabbah 52:5.

- ^ a b c d Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 105b.

- ^ Numbers Rabbah 20:14.

- ^ Mishnah Avot 5:6.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 105a.

- ^ Numbers Rabbah 20:20.

- ^ Deuteronomy Rabbah 3:4.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 105b; see also Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 7a (attributing the interpretation of Micah 6:5 to Rabbi Eleazar.)

- ^ Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 29.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Avodah Zarah 25a.

- ^ Numbers Rabbah 20:11.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 95a.

- ^ See also Genesis 49:9 (twice); Deuteronomy 33:22; Judges 14:5, 8 (twice), 9, 18; 1 Samuel 17:34, 36, 37; 2 Samuel 1:23; 17:10; 23:20; 1 Kings 7:29 (twice), 36; 10:19, 20; 13:24 (twice), 25, 26, 28; 20:36 (twice); 2 Kings 17:25, 26; Isaiah 11:7; 15:9; 21:8; 31:4; 35:9; 38:13; 65:25; Jeremiah 2:30; 4:7; 5:6; 12:8; 49:19; 50:17; 44; 51:38; Ezekiel 1:10; 10:14; 19:2, 6; 22:5; Hosea 11:10; Joel 1:6; Amos 3:4 (twice), 8, 12; 5:19; Micah 5:7; Nahum 2:12 (twice), 13; Zephaniah 3:3; Psalms 7:3; 10:9; 17:12; 22:14, 17, 22; Proverbs 22:13; 26:13; 28:15; Job 4:10; Song 4:8; Lamentations 3:10; Ecclesiastes 9:4; 1 Chronicles 11:22; 12:9; 2 Chronicles 9:18, 19.

- ^ See Judges 14:5; Isaiah 5:29; 11:6; 31:4; Jeremiah 2:15; 25:38; 51:38; Ezekiel 19:2, 3, 5, 6; 32:2; 38:13; 41:19; Hosea 5:14; Amos 3:4; Zechariah 11:3; Micah 5:7; Nahum 2:12, 14; Psalms 17:12; 34:11; 35:17; 58:7; 91:13; 104:21; Proverbs 19:12; 20:2; 28:1; Job 4:10; 38:39.

- ^ See also Genesis 49:9; Deuteronomy 33:20; Isaiah 5:29; 30:6; Ezekiel 19:2; Hosea 13:8; Joel 1:6; Nahum 2:12–13; Psalm 57:5; Job 4:11; 38:39.

- ^ See Isaiah 30:6; Proverbs 30:30; Job 4:11.

- ^ See Hosea 5:14; 13:7; Psalm 91:13; Proverbs 26:13; Job 4:10; 28:8.

- ^ See Job 28:8.

- ^ Tosefta Shabbat 8:23.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 60a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Niddah 31a.

- ^ Exodus Rabbah 30:24.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 106a.

- ^ Exodus Rabbah 50:3.

- ^ Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, chapter 47.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 14a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 40b.

- ^ a b c Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 82a.

- ^ Jerusalem Talmud Sanhedrin 9:7.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 82a–b.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 82b.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Chullin 134b.

- ^ a b Mishnah Sanhedrin 9:6; Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 81b.

- ^ See Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 82b, Sotah 43a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Bava Batra 109b–10a; see also Exodus Rabbah 7:5.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sotah 22b.

- ^ For more on medieval Jewish interpretation, see, e.g., Barry D. Walfish, “Medieval Jewish Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, Jewish Study Bible, 2nd edition, pages 1891–915.

- ^ Rashi. Commentary on Numbers 22:23 (Troyes, France, late 11th century), in, e.g., Rashi, The Torah: With Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated, translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1994), volume 4 (Bamidbar/Numbers), pages 279–80.

- ^ Abraham ibn Ezra, Commentary on Numbers 22:33 (mid-12th century), in, e.g., H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, translators, Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Numbers (Ba-Midbar) (New York: Menorah Publishing Company, 1999), page 189.

- ^ Rashi. Commentary to Numbers 23:10, in, e.g., Rashi, The Torah: With Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated, translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, volume 4 (Bamidbar/Numbers), page 292.

- ^ Judah Halevi, Kitab al Khazari part 1, ¶ 115 (Toledo, Spain, 1130–1140), in, e.g., Jehuda Halevi, The Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith of Israel, introduction by Henry Slonimsky (New York: Schocken, 1964), pages 79–80.

- ^ Abraham ibn Ezra, Commentary on Numbers 23:10, in, e.g., H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, translators, Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Numbers (Ba-Midbar), page 196.

- ^ Nachmanides, Commentary on the Torah (Jerusalem, circa 1270), in, e.g., Charles B. Chavel, translator, Ramban (Nachmanides): Commentary on the Torah: Numbers (New York: Shilo Publishing House, 1975), volume 4, pages 268.

- ^ Bahya ben Asher, Commentary on the Torah (Spain, early 14th century), in, e.g., Eliyahu Munk, translator, Midrash Rabbeinu Bachya: Torah Commentary by Rabbi Bachya ben Asher (Jerusalem: Lambda Publishers, 2003), volume 6, pages 2213–15.

- ^ Maimonides, Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Issurei Bi'ah (The Laws Governing Forbidden Sexual Relationships), chapter 12, halachot 4–5 (Egypt, circa 1170–1180), in, e.g., Eliyahu Touger, translator, Mishneh Torah: Sefer Kedushim: The Book of Holiness (New York: Moznaim Publishing, 2002), pages 150–53.

- ^ Baḥya ibn Paquda, Chovot HaLevavot (Duties of the Heart), section 4, chapter 4 (Zaragoza, Al-Andalus, circa 1080), in, e.g., Bachya ben Joseph ibn Paquda, Duties of the Heart, translated by Yehuda ibn Tibbon and Daniel Haberman (Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1996), volume 1, page 447 (quoting Babylonian Talmud Sotah 22b).

- ^ Baruch Spinoza, Theologico-Political Treatise, chapter 3 (Amsterdam, 1670), in, e.g., Baruch Spinoza, Theological-Political Treatise, translated by Samuel Shirley (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2nd edition, 2001), pages 40–41.

- ^ Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Narrative (New York: Basic Books, 1981), pages 104–05.

- ^ Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L. Weiss, editors, The Torah: A Women's Commentary (New York: Women of Reform Judaism/URJ Press, 2008), page 937.

- ^ Diane Aronson Cohen, "The End of Abuse," in Elyse Goldstein, editor, The Women's Torah Commentary: New Insights from Women Rabbis on the 54 Weekly Torah Portions (Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2000), pages 301–06.

- ^ Nehama Leibowitz, Studies in Bamidbar (Numbers) (Jerusalem: Haomanim Press, 1993) , pages 282–84, 286, reprinted as New Studies in the Weekly Parasha (Lambda Publishers, 2010).

- ^ Nehama Leibowitz, Studies in Bamidbar (Numbers), page 286.

- ^ Dennis T. Olson, Numbers: Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching (Louisville, Kentucky: John Knox Press, 1996), pages 153–54.

- ^ Exodus 32:6; Numbers 25:2.

- ^ Exodus 12:35 and 32:2–4.

- ^ Numbers 25:1–2, 6.

- ^ Exodus 32:28.

- ^ Numbers 25:5.

- ^ Exodus 32:25, 29.

- ^ Numbers 25:6–13.

- ^ Exodus 32:30.

- ^ Numbers 25:13.

- ^ Exodus 32:35; Numbers 25:9.

- ^ George Buchanan Gray, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on Numbers: The International Critical Commentary (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1903), pages 381–82.

- ^ Tikva Frymer-Kensky, Reading the Women of the Bible, pages 216–17.

- ^ Tikva Frymer-Kensky, Reading the Women of the Bible, page 257.

- ^ Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin, Ha'emek Davar (The Depth of the Matter) (Valozhyn, late 19th century), quoted in Nehama Leibowitz, Studies in Bamidbar (Numbers), page 331.

- ^ The Torah: A Women's Commentary. Edited by Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L. Weiss, page 963.

- ^ Maimonides, Mishneh Torah (Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180), in Maimonides, The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides, translated by Charles B. Chavel (London: Soncino Press, 1967); Charles Wengrov, translator, Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education (Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1988), volume 4, page 171.

- ^ "Parashat Chukat-Balak". Hebcal. Retrieved July 9, 2016.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Makkot 23b–24a.

- ^ Menachem Davis, The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals with an Interlinear Translation (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002), pages 571, 578–79.

- ^ Menachem Davis, editor, The Interlinear Haggadah: The Passover Haggadah, with an Interlinear Translation, Instructions and Comments (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2005), page 107.

- ^ Reuven Hammer, Or Hadash: A Commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals (New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2003) , page 61; see also Edward Feld, editor, Siddur Lev Shalem for Shabbat and Festivals (New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2016), page 101; Menachem Davis, editor, Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals, page 192; Menachem Davis, editor, The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for Weekdays with an Interlinear Translation (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002), page 14.

- ^ See Mark L. Kligman, "The Bible, Prayer, and Maqam: Extra-Musical Associations of Syrian Jews," Ethnomusicology, volume 45 (number 3) (Autumn 2001): pages 443–79; Mark L. Kligman, Maqam and Liturgy: Ritual, Music, and Aesthetics of Syrian Jews in Brooklyn (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2009).

Further reading

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Ancient

- Deir Alla Inscription. Deir Alla, circa 9th–8th century BCE. In, e.g., "The Deir ʿAlla Plaster Inscriptions (2.27) (The Book of Balaam, son of Beor)." In The Context of Scripture, Volume II: Monumental Inscriptions from the Biblical World. Edited by William W. Hallo, pages 140–45. New York: Brill, 2000. See also Jo Ann Hackett, Balaam Text from Deir 'Alla. Chico, California: Scholars Press, 1984.

Biblical

- Genesis 3:1–14 (talking animal); 22:3 (rose early in the morning, and saddled his ass, and took two of his young men with him).

- Exodus 32:1–35 (sacrifices to another god; zealots kill apostates; zealots rewarded with priestly standing; plague as punishment; leader makes atonement); 34:15–16 (foreign women and apostasy).

- Numbers 31:6–18 (Balaam; Phinehas, war with Midian).

- Deuteronomy 4:3 (Baal Peor); 23:4–7 (Balaam).

- Joshua 13:22 (Balaam the son of Beor the sorcerer); 22:16–18 (Baal Peor); 24:9–10.

- Jeremiah 30:18 (tents, dwellings).

- Hosea 9:10 (Baal Peor).

- Micah 6:5 (Balaam).

- Nehemiah 13:1–2.

- Psalms 1:3 (like a tree planted); 31:19 (lying lips be dumb); 33:10–11 (God brings the counsel of the nations to nothing); 49:17–18 (disregard for the wealth of this world); 78:2 (speaking a parable); 98:6 (shout); 106:28–31 (Baal Peor); 110:2 (rod out of Zion); 116:15 (precious to God the death of God's servants).

Early nonrabbinic

- 1 Maccabees chs. 1–16. (parallel to Phinehas).

- 4 Maccabees 18:12.

- Instruction for Catechumens, and A Prayer of Praise of God for His Greatness, and for His Appointment of Leaders for His People. In "Hellenistic Synagogal Prayers," in James H. Charlesworth. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, volume 2, pages 687–88. New York: Doubleday, 1985.

- Pseudo-Philo 18:1–14; 28:1–4. Land of Israel, 1st century. In, e.g., The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: Volume 2: Expansions of the "Old Testament" and Legends, Wisdom and Philosophical Literature, Prayers, Psalms, and Odes, Fragments of Lost Judeo-Hellenistic works. Edited by James H. Charlesworth, pages 324–36. New York: Anchor Bible, 1985.

- Matthew 2:1–12. Antioch, circa 80–90. (See also R.E. Brown, "The Balaam Narrative," The Birth of the Messiah, pages 190–96. Garden City, New York, 1977.)

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 6:1–7 Archived 2006-08-03 at the Wayback Machine. Circa 93–94. In, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, pages 108–10. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987.

- 2 Peter 2:15 (Balaam).

- Jude 1:11 (Balaam).

- Revelation 2:14 Late 1st century. (Balaam).

Classical rabbinic

- Mishnah: Sanhedrin 9:6; 10:2; Avot 5:6, 19. Land of Israel, circa 200 CE. In, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 604, 686, 689. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

- Tosefta Shabbat 8:23. Land of Israel, circa 250 CE. In, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, pages 384–85. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Maaser Sheni 44b; Shabbat 48b; Beitzah 45a; Rosh Hashanah 20b; Taanit 10a, 27b; Nedarim 12a; Sotah 28b, 47b; Sanhedrin 10a, 60b, 66a–b; Shevuot 13b. Tiberias, Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. In, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volumes 10, 14, 23–25, 33, 36–37, 44–46. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2006–2019. And in, e.g., The Jerusalem Talmud: A Translation and Commentary. Edited by Jacob Neusner and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, B. Barry Levy, and Edward Goldman. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2009.

- Genesis Rabbah 18:5; 19:11; 39:8; 41:3; 51:10–11; 52:5; 53:4; 55:8. Land of Israel, 5th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 1, pages 143–45, 156–57, 316, 334, 449–50, 453–54, 463–64, 488–89; volume 2, pages 603, 655, 662, 680–81, 862, 876, 886, 955, 981–82. London: Soncino Press, 1939.

- Babylonian Talmud: Berakhot 7a, 12b, 16a, 38a; Shabbat 64a, 105a; Pesachim 54a, 111a; Rosh Hashanah 11a, 32b; Taanit 20a; Chagigah 2a; Nedarim 32a, 81a; Nazir 23b; Sotah 10a, 11a, 14a, 22b, 41b, 43a, 46b, 47a; Gittin 68b; Kiddushin 4a; Bava Kamma 38a; Bava Batra 14b, 60a, 109b; Sanhedrin 34b–35a, 39b, 40b, 44a, 56a, 64a, 82a, 92a, 93b, 105a–06a; Makkot 10b; Avodah Zarah 4b, 25a, 44b; Horayot 10b; Menachot 66b; Chullin 19b, 35b, 134b; Bekhorot 5b; Keritot 22a; Niddah 19b, 31a, 55b. Sasanian Empire, 6th century. In, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 volumes. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

Medieval

- Solomon ibn Gabirol. A Crown for the King, 36:493. Spain, 11th century. Translated by David R. Slavitt, pages 66–67. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Rashi. Commentary. Numbers 22–25. Troyes, France, late 11th century. In, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, volume 4, pages 269–317. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997.

- Rashbam. Commentary on the Torah. Troyes, early 12th century. In, e.g., Rashbam's Commentary on Leviticus and Numbers: An Annotated Translation. Edited and translated by Martin I. Lockshin, pages 263–84. Providence: Brown Judaic Studies, 2001.

- , Spain, 1130–1140. In, e.g., Jehuda Halevi. Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith of Israel. Introduction by Henry Slonimsky, page 80. New York: Schocken, 1964.

- Numbers Rabbah 20:1–25. 12th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 26, 37, 44, 46, 55, 368, 407, 420, 470, 484; volume 6, pages 630, 634–35, 786–826, 829, 856, 873. London: Soncino Press, 1939.

- Abraham ibn Ezra. Commentary on the Torah. Mid-12th century. In, e.g., Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Numbers (Ba-Midbar). Translated and annotated by H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, pages 178–215. New York: Menorah Publishing Company, 1999.

- .

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Shofar, Sukkah, V’Lulav (The Laws of the Shofar, Sukkah, and Lulav), chapter 3, ¶ 9. Egypt, circa 1170–1180. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Shofar, Sukkah, V’Lulav: The Laws of Shofar, Sukkah, and Lulav. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 56–60. New York: Moznaim Publishing, 1988.

- Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. In, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, pages 17, 29, 105, 235, 242, 264, 288, 298. New York: Dover Publications, 1956.

- Hezekiah ben Manoah. Hizkuni. France, circa 1240. In, e.g., Chizkiyahu ben Manoach. Chizkuni: Torah Commentary. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 980–96. Jerusalem: Ktav Publishers, 2013.

- Nachmanides. Commentary on the Torah. Jerusalem, circa 1270. In, e.g., Ramban (Nachmanides): Commentary on the Torah: Numbers. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 4, pages 245–95. New York: Shilo Publishing House, 1975.

- Zohar, part 3, pages 184b–212b. Spain, late 13th century. In, e.g., The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 volumes. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

- Jacob ben Asher (Baal Ha-Turim). Rimze Ba'al ha-Turim. Early 14th century. In, e.g., Baal Haturim Chumash: Bamidbar/Numbers. Translated by Eliyahu Touger; edited and annotated by Avie Gold, volume 4, pages 1619–65. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2003.

- Jacob ben Asher. Perush Al ha-Torah. Early 14th century. In, e.g., Yaakov ben Asher. Tur on the Torah. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 1152–79. Jerusalem: Lambda Publishers, 2005.

- Isaac ben Moses Arama. Akedat Yizhak (The Binding of Isaac). Late 15th century. In, e.g., Yitzchak Arama. Akeydat Yitzchak: Commentary of Rabbi Yitzchak Arama on the Torah. Translated and condensed by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 762–77. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2001.

Modern

- Isaac Abravanel. Commentary on the Torah. Italy, between 1492 and 1509. In, e.g., Abarbanel: Selected Commentaries on the Torah: Volume 4: Bamidbar/Numbers. Translated and annotated by Israel Lazar, pages 238–73. Brooklyn: CreateSpace, 2015.

- Obadiah ben Jacob Sforno. Commentary on the Torah. Venice, 1567. In, e.g., Sforno: Commentary on the Torah. Translation and explanatory notes by Raphael Pelcovitz, pages 764–83. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997.

- Moshe Alshich. Commentary on the Torah. Safed, circa 1593. In, e.g., Moshe Alshich. Midrash of Rabbi Moshe Alshich on the Torah. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 891–910. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2000.

- Israel ben Banjamin of Bełżyce. "Sermon on Balaq." Bełżyce, 1648. In Marc Saperstein. Jewish Preaching, 1200–1800: An Anthology, pages 286–300. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

- Avraham Yehoshua Heschel. Commentaries on the Torah. Targum Press/Feldheim Publishers, 2004.

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan, Review & Conclusion. England, 1651. Reprint edited by C. B. Macpherson, pages 723–24. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Classics, 1982.

- Shabbethai Bass. Sifsei Chachamim. Amsterdam, 1680. In, e.g., Sefer Bamidbar: From the Five Books of the Torah: Chumash: Targum Okelos: Rashi: Sifsei Chachamim: Yalkut: Haftaros, translated by Avrohom Y. Davis, pages 389–459. Lakewood Township, New Jersey: Metsudah Publications, 2013.

- Chaim ibn Attar. Ohr ha-Chaim. Venice, 1742. In Chayim ben Attar. Or Hachayim: Commentary on the Torah. Translated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 4, pages 1568–636. Brooklyn: Lambda Publishers, 1999.

- Samuel David Luzzatto (Shadal). Commentary on the Torah. Padua, 1871. In, e.g., Samuel David Luzzatto. Torah Commentary. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 1089–1106. New York: Lambda Publishers, 2012.

- Marcus M. Kalisch. The Prophecies of Balaam (Numbers XXII to XXIV): or, The Hebrew and the Heathen. London: Longmans, Green, and Company, 1877–1878. Reprinted BiblioLife, 2009.

- Samuel Cox. Balaam: An Exposition and a Study. London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Co., 1884. Reprinted Palala Press, 2015.

- Rufus P. Stebbins. "The Story of Balaam." The Old Testament Student, volume 4 (number 9) (May 1885): pages 385–95.

- Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter. Sefat Emet. Góra Kalwaria (Ger), Poland, before 1906. Excerpted in The Language of Truth: The Torah Commentary of Sefat Emet. Translated and interpreted by Arthur Green, pages 257–62. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1998. Reprinted 2012.

- Julius A. Bewer. "The Literary Problems of the Balaam Story in Numb., Chaps. 22–24". The American Journal of Theology, volume 9 (number 2) (April 1905): pages 238–62.

- Hermann Cohen. Religion of Reason: Out of the Sources of Judaism. Translated with an introduction by Simon Kaplan; introductory essays by Leo Strauss, pages 149, 232, 341. New York: Ungar, 1972. Reprinted Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995. Originally published as Religion der Vernunft aus den Quellen des Judentums. Leipzig: Gustav Fock, 1919.

- Ben Zion Bokser, page 118. Mahwah, New Jersey: Paulist Press 1978.

- Alexander Alan Steinbach. Sabbath Queen: Fifty-four Bible Talks to the Young Based on Each Portion of the Pentateuch, pages 126–29. New York: Behrman's Jewish Book House, 1936.

- Julius H. Greenstone. Numbers: With Commentary: The Holy Scriptures, pages 220–79. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1939. Reprinted by Literary Licensing, 2011.

- Gilmore H. Guyot. "Balaam." Catholic Biblical Quarterly, volume 3 (number 3) (July 1941): pages 235–42.

- Stefan C. Reif. "What Enraged Phinehas?: A Study of Numbers 25:8". Journal of Biblical Literature, volume 90 (number 2) (June 1971): pages 200–06.

- Jacob Hoftijzer. "The Prophet Balaam in a 6th Century Aramaic Inscription". Biblical Archaeologist, volume 39 (number 1) (March 1976): pages 11–17.

- Ira Clark. "Balaam's Ass: Suture or Structure". In Literary Interpretations of Biblical Narratives: Volume II. Edited by Kenneth R.R. Gros Louis, with James S. Ackerman, pages 137–44. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1982.

- Vigiliae Christianae, volume 37 (number 1) (March 1983): pages 22–35.

- Judith R. Baskin. Pharaoh's Counsellors: Job, Jethro, and Balaam in Rabbinic and Patristic Tradition. Brown Judaic Studies, 1983.

- Philip J. Budd. Word Biblical Commentary: Volume 5: Numbers, pages 248–83. Waco, Texas: Word Books, 1984.

- André Lemaire. "Fragments from the Book of Balaam Found at Deir Alla: Text foretells cosmic disaster". Biblical Archaeology Review, volume 11 (number 5) (September/October 1985).

- Biblical Archaeologist, volume 49 (1986): pages 216–22.

- Pinchas H. Peli. Torah Today: A Renewed Encounter with Scripture, pages 181–83. Washington, D.C.: B'nai B'rith Books, 1987.

- Jonathan D. Safren. "Balaam and Abraham". Vetus Testamentum, volume 38 (number 1) (January 1988): pages 105–13.

- Jacob Milgrom. The JPS Torah Commentary: Numbers: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation, pages 185–215, 467–80. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1990.

- Mark S. Smith. The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel, pages 21, 23, 29, 51, 63, 127–28. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1990.

- The Balaam Text from Deir `Alla Re-evaluated: Proceedings of the International Symposium Held at Leiden, 21–24 August 1989. Edited by J. Hoftijzer and G. van der Kooij. New York: E. J. Brill, 1991.

- Mary Douglas. In the Wilderness: The Doctrine of Defilement in the Book of Numbers, pages xix, 86–87, 100, 121, 123, 136, 188, 191, 200–01, 211, 214, 216–18, 220–24. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. Reprinted 2004.

- Mary Douglas. Balaam's Place in the Book of Numbers". Man, volume 28 (new series) (number 3) (September 1993): pages 411–30.

- Aaron Wildavsky. Assimilation versus Separation: Joseph the Administrator and the Politics of Religion in Biblical Israel, page 31. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 1993.

- Judith S. Antonelli. "Kazbi: Midianite Princess". In In the Image of God: A Feminist Commentary on the Torah, pages 368–76. Northvale, New Jersey: Jason Aronson, 1995.

- David Frankel. "The Deuteronomic Portrayal of Balaam". Vetus Testamentum, volume 46 (number 1) (January 1996): pages 30–42.

- Ellen Frankel. The Five Books of Miriam: A Woman's Commentary on the Torah, pages 228–33. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1996.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Haftarah Commentary, pages 387–95. New York: UAHC Press, 1996.

- Sorel Goldberg Loeb and Barbara Binder Kadden. Teaching Torah: A Treasury of Insights and Activities, pages 266–71. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 1997.

- Harriet Lutzky. "Ambivalence toward Balaam." Vetus Testamentum, volume 49 (number 3) (July 1999): pages 421–25.

- Diane Aronson Cohen. "The End of Abuse." In The Women's Torah Commentary: New Insights from Women Rabbis on the 54 Weekly Torah Portions. Edited by Elyse Goldstein, pages 301–06. Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2000.

- Baruch A. Levine. Numbers 21–36, volume 4A, pages 135–303. New York: Anchor Bible, 2000.

- Dennis T. Olson. "Numbers." In The HarperCollins Bible Commentary. Edited by James L. Mays, pages 180–82. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, revised edition, 2000.

- Lainie Blum Cogan and Judy Weiss. Teaching Haftarah: Background, Insights, and Strategies, pages 574–83. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 2002.

- Michael Fishbane. The JPS Bible Commentary: Haftarot, pages 244–50. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2002.

- John J. Collins. "The Zeal of Phinehas: The Bible and the Legitimation of Violence." Journal of Biblical Literature, volume 122 (number 1) (Spring 2003): pages 3–21.

- Martti Nissinen, Choon-Leong Seow, and Robert K. Ritner. Prophets and Prophecy in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Peter Machinist. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2003.

- Robert Alter. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary, pages 795–819. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2004.

- Jane Kanarek. "Haftarat Balak: Micah 5:6–6:8." In The Women's Haftarah Commentary: New Insights from Women Rabbis on the 54 Weekly Haftarah Portions, the 5 Megillot & Special Shabbatot. Edited by Elyse Goldstein, pages 190–94. Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2004.

- Professors on the Parashah: Studies on the Weekly Torah Reading Edited by Leib Moscovitz, pages 275–79. Jerusalem: Urim Publications, 2005.

- Aaron Wildavsky. Moses as Political Leader, pages 50–55. Jerusalem: Shalem Press, 2005.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition. Revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern, pages 1047–71. New York: Union for Reform Judaism, 2006.

- Suzanne A. Brody. "Ma Tovu." In Dancing in the White Spaces: The Yearly Torah Cycle and More Poems, page 99. Shelbyville, Kentucky: Wasteland Press, 2007.

- James L. Kugel. How To Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now, pages 64, 115, 336–40, 421, 440, 622, 658. New York: Free Press, 2007.

- The Torah: A Women's Commentary. Edited by Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L. Weiss, pages 937–60. New York: URJ Press, 2008.

- R. Dennis Cole. "Numbers." In Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary. Edited by John H. Walton, volume 1, pages 378–86. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2009.

- Reuven Hammer. Entering Torah: Prefaces to the Weekly Torah Portion, pages 231–35. New York: Gefen Publishing House, 2009.

- Lori Hope Lefkovitz. "Between Beast and Angel: The Queer, Fabulous Self: Parashat Balak (Numbers 22:2–25:10)." In Torah Queeries: Weekly Commentaries on the Hebrew Bible. Edited by Gregg Drinkwater, Joshua Lesser, and David Shneer; foreword by Judith Plaskow, pages 212–15. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

- Clinton John Moyer. Literary and Linguistic Studies in Sefer Bilʿam (Numbers 22–24). Doctor’s dissertation, Cornell University, 2009.

- Carolyn J. Sharp. “Oracular Indeterminacy and Dramatic Irony in the Story of Balaam.” In Irony and Meaning in the Hebrew Bible, pages 134–51. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2009.

- Kenneth C. Way. “Animals in the Prophetic World: Literary Reflections on Numbers 22 and 1 Kings 13.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, volume 34 (number 1) (September 2009): pages 47–62.

- Terence E. Fretheim. "Numbers." In The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version with the Apocrypha: An Ecumenical Study Bible. Edited by Michael D. Coogan, Marc Z. Brettler, Carol A. Newsom, and Pheme Perkins, pages 222–28. New York: Oxford University Press, Revised 4th Edition 2010.

- Joann Scurlock. “Departure of Ships? An Investigation of יצ in Numbers 24.24 and Isaiah 33.23.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, volume 34 (number 3) (March 2010): pages 267–82.

- Shawn Zelig Aster. “‘Bread of the Dungheap’: Light on Numbers 21:5 from the Tell Fekherye Inscription.” Vetus Testamentum, volume 61 (number 3) (2011): pages 341–58.

- The Commentators' Bible: Numbers: The JPS Miqra'ot Gedolot. Edited, translated, and annotated by Michael Carasik, pages 163–92. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2011.

- Josebert Fleurant. “Phinehas Murdered Moses’ Wife: An Analysis of Numbers 25.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, volume 35 (number 3) (March 2011): pages 285–94.

- Calum Carmichael. "Sexual and Religious Seduction (Numbers 25–31)." In The Book of Numbers: A Critique of Genesis, pages 135–58. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012.

- Shmuel Herzfeld. "Intergenerational Sparring." In Fifty-Four Pick Up: Fifteen-Minute Inspirational Torah Lessons, pages 227–33. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House, 2012.

- Clinton J. Moyer. “Who Is the Prophet, and Who the Ass? Role-Reversing Interludes and the Unity of the Balaam Narrative (Numbers 22–24).” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, volume 37 (number 2) (December 2012): pages 167–83.

- Shlomo Riskin. Torah Lights: Bemidbar: Trials and Tribulations in Times of Transition, pages 179–204. New Milford, Connecticut: Maggid Books, 2012.

- Mark Douek. "A Righteous Balaam: Balaam's Character According to Maimonides." (2013).

- Nili S. Fox. "Numbers." In The Jewish Study Bible, 2nd edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Haim O. Rechnitzer. "The Magical Mystery Tour: The stage is set for the final battle between the mystical mode and the magical one." The Jerusalem Report, volume 25 (number 7) (July 14, 2014): page 47.

- Avivah Gottlieb Zornberg. Bewilderments: Reflections on the Book of Numbers, pages 234–62. New York: Schocken Books, 2015.

- Jonathan Sacks. Lessons in Leadership: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible, pages 217–20. New Milford, Connecticut: Maggid Books, 2015.

- Jonathan Sacks. Essays on Ethics: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible, pages 251–55. New Milford, Connecticut: Maggid Books, 2016.

- Shai Held. The Heart of Torah, Volume 2: Essays on the Weekly Torah Portion: Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, pages 158–67. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2017.

- Steven Levy and Sarah Levy. The JPS Rashi Discussion Torah Commentary, pages 134–37. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2017.

- Jonathan Sacks. Numbers: The Wilderness Years: Covenant & Conversation: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible, pages 283–312. New Milford, Connecticut: Maggid Books, 2017.

External links

Texts

Commentaries

- Academy for Jewish Religion, California

- Academy for Jewish Religion, New York

- Aish.com

- American Jewish University—Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies

- Chabad.org

- Hadar Institute

- Jewish Theological Seminary

- MyJewishLearning.com

- Orthodox Union

- Pardes from Jerusalem

- Reconstructing Judaism

- Union for Reform Judaism

- United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism

- Yeshiva University