Bali tiger

| Bali tiger | |

|---|---|

| |

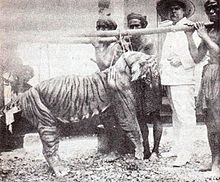

| A Bali tiger killed by M. Zanveld in the 1920s | |

Extinct (1950s)

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. tigris |

| Subspecies: | P. t. sondaica

|

| Population: | †Bali tiger |

The Bali tiger was a

It was formerly regarded as a distinct

Results of a

In Bali, the last tigers were recorded in the late 1930s. A few individuals likely survived into the 1940s and possibly 1950s. The population was hunted to

Balinese names for the tiger are harimau Bali and samong.[5]

Taxonomic history

In 1912, the German zoologist

In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the

Characteristics

The Bali tiger was described as the smallest tiger in the

Habitat and ecology

Most of the known Bali tiger zoological specimens originated in western Bali, where mangrove forests, dunes and savannah vegetation existed. The main prey of the Bali tiger was likely the Javan rusa (Rusa timorensis).[10]

Extinction

At the end of the 19th century,

A few tiger skulls, skins and bones are preserved in museums.

Cultural significance

The tiger had a well-defined position in Balinese folkloric beliefs and magic. It is mentioned in folk tales and depicted in traditional arts, as in the

Balinese people are fond of wearing tiger parts as jewelry for status or spiritual reasons, such as power and protection. Necklaces of teeth and claws or male rings cabochoned with polished tiger tooth ivory still exist in everyday use. Since the tiger has disappeared on both Bali and neighboring Java, old parts have been recycled, or leopard and sun bear body parts have been used instead.[citation needed]

See also

- Tiger populations

- Mainland Asian populations

- Sunda island populations

- Prehistoric tigers: Panthera tigris soloensis

- Panthera tigris trinilensis

- Panthera tigris acutidens

- Holocene extinction

References

- ^ a b c Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O'Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 66–68.

- ^ a b Goodrich, J.; Lynam, A.; Miquelle, D.; Wibisono, H.; Kawanishi, K.; Pattanavibool, A.; Htun, S.; Tempa, T.; Karki, J.; Jhala, Y.; Karanth, U. (2015). "Panthera tigris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T15955A50659951.

- ^ PMID 25754539.

- ISBN 978-0-8155-1133-5.

- ^ Crawfurd, J. (1820). History of The Indian Archipelago, Volume II. Edinburgh: Archibald Constable & Co.

- ^ .

- ^ Hemmer, H. (1969). "Zur Stellung des Tigers (Panthera tigris) der Insel Bali". Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 34: 216–223.

- ^ Mazak, V.; Groves, C. P.; Van Bree, P. (1978). "Skin and Skull of the Bali Tiger, and a list of preserved specimens of Panthera tigris balica (Schwarz, 1912)". Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 43 (2): 108–113.

- JSTOR 3504004.

- ^ a b c Seidensticker, J. (1986). "Large carnivores and the consequences of habitat insularization: ecology and conservation of tigers in Indonesia and Bangladesh". In S. D. Miller; D. D. Everett (eds.). Cats of the World: biology, conservation, and management. Washington DC: National Wildlife Federation. pp. 1–41.

- ^ Vojnich, G. (1913). A Kelet-Indiai Szigetcsoporton [in the East Indian Archipelago]. Budapest: Singer és Wolfner.

- ^ Buzas, B. and Farkas, B. (1997). An additional skull of the Bali tiger, Panthera tigris balica (Schwarz) in the Hungarian Natural History Museum. Miscellanea Zoologica Hungarica Volume 11: 101–105.

- ^ Covarrubias, M. (1937). Island Of Bali. New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc. p. 105.

- JSTOR 43563555.

External links

- "Tiger Bali tiger (P. t. balica)". IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group.

- "Death of the Bali Tiger". Save The Tiger Fund. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11.