Banksia verticillata

| Granite banksia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Proteaceae |

| Genus: | Banksia |

| Species: | B. verticillata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Banksia verticillata | |

| |

| Distribution of B. verticillata in Western Australia. | |

Banksia verticillata, commonly known as granite banksia or Albany banksia, is a species of

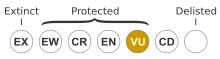

A declared vulnerable species, it occurs in two disjunct populations on granite outcrops along the south coast of Western Australia, with the main population near Albany and a smaller population near Walpole, and is threatened by dieback (Phytophthora cinnamomi) and aerial canker (Zythiostroma). B. verticillata is killed by bushfire and new plants regenerate from seed afterwards. Populations take over a decade to produce seed and fire intervals of greater than twenty years are needed to allow the canopy seed bank to accumulate.

Description

Banksia verticillata grows as a spreading, bushy shrub with many branches up to 3 m (10 ft) high, but can reach 5 m (16 ft) high in sheltered locations.

Taxonomy

Discovery and naming

The earliest known botanical collection of B. verticillata was made by Scottish surgeon and naturalist

The next known collection was in December 1801, during the visit of

Brown formally described and named the species in his 1810

No

Infrageneric placement

In

For many years there was confusion between B. verticillata and B. littoralis (swamp banksia). Until 1984, the latter was circumscribed as encompassing what is now Banksia seminuda (river banksia), which has whorled leaves like B. verticillata. Thus it was easy to perceive B. verticillata as falling within the range of variation of this broadly defined species. The confusion was largely cleared up once B. seminuda was recognised as a distinct taxon.[24]

Alex George published a new taxonomic arrangement of Banksia in his landmark 1981 monograph The genus Banksia L.f. (Proteaceae). Endlicher's Eubanksia became B. subg. Banksia, and was divided into three sections, one of which was Oncostylis. Oncostylis was further divided into four series, with B. verticillata placed in series Spicigerae because its inflorescences are cylindrical.[4]

In 1996,

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

This clade became the basis of Thiele and Ladiges'

- Banksia

- B. subg. Banksia

- B. sect. Banksia (9 series, 50 species, 9 subspecies, 3 varieties)

- B. sect. Coccinea(1 species)

- B. sect. Oncostylis

- B. ser. Spicigerae (7 species, 2 subspecies, 4 varieties)

- B. spinulosa (4 varieties)

- B. ericifolia (2 subspecies)

- B. verticillata

- B. seminuda

- B. littoralis

- B. occidentalis

- B. brownii

- B. ser. Tricuspidae(1 species)

- B. ser. Dryandroideae (1 species)

- B. ser. Abietinae (13 species, 2 subspecies, 9 varieties)

- B. ser. Spicigerae (7 species, 2 subspecies, 4 varieties)

- B. subg. Isostylis (3 species)

- B. subg. Banksia

More recent molecular research by Austin Mast and colleagues provide further support of B. verticillata's placement among its nearest relatives, but these do not appear to be closely related to the remaining members of B. ser. Spicigerae, but rather occur in a clade that is sister (next closest relative) to B. nutans:[26]

(B. seminuda is omitted because it was not sampled in the study, not because it occurs elsewhere in the cladogram.)

Distribution and habitat

Banksia verticillata is found in scattered populations in two disjunct segments: one clustered around

Ecology

The New Holland honeyeater (Phylidonyris novaehollandiae) is a major visitor and pollinator of Banksia verticillata. These birds can travel 15 m (50 ft) between inflorescences in a feeding session, and preferentially choose flower spikes with partly opened flowers. Other honeyeater species observed, the white-cheeked honeyeater (Phylidonyris nigra) and western spinebill (Acanthorhynchus superciliosus), visit this species to a much lesser extent.[2] The brown honeyeater (Lichmera indistincta) has also been recorded as a visitor.[28] Small mammals are not major pollinators, although bush rats (Rattus fuscipes) and house mice (Mus musculus) have been recorded. Honey bees (Apis mellifera) visit flower spikes but are not effective pollinators.[2][5]

B. verticillata is significantly threatened by at least three microorganisms. Several populations have reduced or vanished from dieback (Phytophthora cinnamomi), such as those at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and Gull Rock National Park. The honey fungus Armillaria luteobubalina has killed plants in Torndirrup National Park, and aerial canker (Zythiostroma) has decimated populations at Waychinicup National Park east of Albany.[2]

B. verticillata plants are generally killed by fire and regenerate from seed. A

Conservation

Banksia verticillata has been declared vulnerable under the federal

Cultivation

Banksia verticillata is seldom seen in

References

- ^ a b Banksia verticillata — Granite Banksia, Albany Banksia, River Banksia, Species Profile and Threats Database, Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australia.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kelly, Anne E.; Coates, David (1995). Population dynamics, reproductive biology and conservation of Banksia brownii and Banksia verticillata. ANCA ESP Project No. 352. Como, Western Australia: Department of Environment and Conservation, Government of Western Australia.

- ^ Atkins, K. J. (1998). Conservation Statements for threatened flora within the regional forest agreement region for Western Australia. Como, Western Australia: Department of Environment and Conservation, Government of Western Australia. pp. 1–95.

- ^ ISBN 0-643-06454-0.

- ^ a b Rees, R.G.; Collins, B.G. (1994). Reproductive biology and pollen vectors of the rare and endangered Banksia verticillata R.Br. pp. 1–35. School of Environmental Biology. Curtin University of Technology, Perth.

- ^ ISBN 1-920843-20-5.

- ISBN 1-4446-8481-7.

The individual here given, remarkable for its verticillate entire leaves, of a pure white on the under side, was discovered by Mr Menzies in New Holland, and brought by him to our gardens in 1794.

- ^ "Banksia verticillata". Robert Brown's Australian Botanical Specimens, 1801–1805 at the BM. Western Australian Herbarium, Department of Environment and Conservation, Government of Western Australia. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- .

- ISBN 0-642-56817-0.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link - )

- ISBN 0-85091-346-2.

- S2CID 140671788.

- ^ .

- ^ ISSN 0085-4417.

- ISBN 978-1-876473-58-7.

- ^ "Banksia verticillata R.Br". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government.

- ^ Kuntze, Otto (1891). Revisio generum plantarum. Vol. 2. Leipzig: Arthur Felix. pp. 581–582.

- JSTOR 4107078.

- JSTOR 4111642.

- ^ Endlicher, Stephan (1847). "Pars II. CXIII". Genera Plantarum Secundum Ordines Naturales Disposita: Supplement IV (in Latin). pp. 88–89. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- Prodromus systematis naturalis regni vegetabilis. Vol. 14. Paris: Sumptibus Sociorum Treuttel et Wurtz.

- ^ Bentham, George (1870). "Banksia". Flora Australiensis. Vol. 5. London: L. Reeve & Co. pp. 541–62.

- ISBN 0-85179-864-0.

- ^ .

- PMID 21665734.

- ISBN 0-644-07124-9. pp. 240–41

- ISBN 0-643-05006-X.

- ISBN 0-949324-66-3.

- Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions.

- ^ a b "Approved Conservation Advice for Banksia verticillata (Granite Banksia)" (PDF). Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts website. Canberra, ACT: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Australian Government. 26 March 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ISSN 0815-4465.

- S2CID 7742365.

- doi:10.1071/BT01018.

- ISBN 0-85091-143-5.

- ISSN 0728-2893.

- ISBN 0-643-09298-6.

External links

- "Banksia verticillata R.Br". Flora of Australia Online. Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australian Government.

- "Banksia verticillata R.Br". Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions.

- "Banksia verticillata R.Br". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI), IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government.

- Banksia verticillata — Granite Banksia, Albany Banksia, River Banksia, Species Profile and Threats Database, Department of the Environment and Heritage, Australia.