Baryte

| Baryte (barite) | ||

|---|---|---|

Specific gravity 4.3–5 | | |

| Density | 4.48 g/cm3[2] | |

| Optical properties | biaxial positive | |

| Refractive index | nα = 1.634–1.637 nβ = 1.636–1.638 nγ = 1.646–1.648 | |

| Birefringence | 0.012 | |

| Fusibility | 4, yellowish green barium flame | |

| Diagnostic features | white color, high specific gravity, characteristic cleavage and crystals | |

| Solubility | low | |

| References | [3][4][5][6] | |

Baryte, barite or barytes (/ˈbæraɪt, ˈbɛər-/[7] or /bəˈraɪtiːz/[8]) is a mineral consisting of barium sulfate (BaSO4).[3] Baryte is generally white or colorless, and is the main source of the element barium. The baryte group consists of baryte, celestine (strontium sulfate), anglesite (lead sulfate), and anhydrite (calcium sulfate). Baryte and celestine form a solid solution (Ba,Sr)SO4.[2]

Names and history

The radiating form, sometimes referred to as Bologna Stone,

The American Petroleum Institute specification API 13/ISO 13500, which governs baryte for drilling purposes, does not refer to any specific mineral, but rather a material that meets that specification.[13] In practice, however, this is usually the mineral baryte.[14]

The term "primary barytes" refers to the first marketable product, which includes crude baryte (run of mine) and the products of simple

Name

The name baryte is derived from the

Other names have been used for baryte, including barytine,[18] barytite,[18] barytes,[19] heavy spar,[3] tiff,[4] and blanc fixe.[20]

Mineral associations and locations

Baryte occurs in many depositional environments, and is deposited through many processes including biogenic, hydrothermal, and evaporation, among others.[2] Baryte commonly occurs in lead-zinc veins in limestones, in hot spring deposits, and with hematite ore. It is often associated with the minerals anglesite and celestine. It has also been identified in meteorites.[21]

Baryte has been found at locations in Australia, Brazil, Nigeria, Canada, Chile, China, India, Pakistan, Germany, Greece, Guatemala, Iran, Ireland (where it was mined on

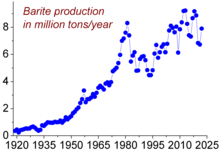

The global production of baryte in 2019 was estimated to be around 9.5 million metric tons, down from 9.8 million metric tons in 2012.[25] The major barytes producers (in thousand tonnes, data for 2017) are as follows: China (3,600), India (1,600), Morocco (1,000), Mexico (400), United States (330), Iran (280), Turkey (250), Russia (210), Kazakhstan (160), Thailand (130) and Laos (120).[26]

The main users of barytes in 2017 were (in million tonnes) US (2.35), China (1.60), Middle East (1.55), the European Union and Norway (0.60), Russia and CIS (0.5), South America (0.35), Africa (0.25), and Canada (0.20). 70% of barytes was destined for oil and gas well drilling muds. 15% for barium chemicals, 14% for filler applications in automotive, construction, and paint industries, and 1% other applications.[26]

Natural baryte formed under

Information about the mineral resource base of baryte ores is presented in some scientific articles.[29]

Uses

In oil and gas drilling

Worldwide, 69–77% of baryte is used as a weighting agent for

In oxygen and sulfur isotopic analysis

In the deep ocean, away from continental sources of sediment,

The variations in

Geochronological dating

Dating the baryte in hydrothermal vents has been one of the major methods to know the ages of hydrothermal vents.[31][32][33][34][35] Common methods to date hydrothermal baryte include radiometric dating[31][32] and electron spin resonance dating.[33][34][35]

Other uses

Baryte is used in added-value applications which include filler in paint and plastics, sound reduction in engine compartments, coat of automobile finishes for smoothness and corrosion resistance, friction products for automobiles and trucks,

Historically, baryte was used for the production of

Although baryte contains the toxic alkaline earth metal barium, it is not detrimental for human health, animals, plants and the environment because barium sulfate is extremely insoluble in water.

It is also sometimes used as a gemstone.[36]

See also

- Hokutolite

- Rose rock

References

- S2CID 235729616.

- ^ ISBN 0-939950-52-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dana, James Dwight; Ford, William Ebenezer (1915). Dana's Manual of Mineralogy for the Student of Elementary Mineralogy, the Mining Engineer, the Geologist, the Prospector, the Collector, Etc (13 ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 299–300.

- ^ a b Barite at Mindat

- ^ Webmineral data for barite

- ^ Baryte, Handbook of Mineralogy

- ^ "baryte". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on March 8, 2020.

- ^ "barytes". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary.

- ISBN 0922152349.

- ^ History of the Bologna stone Archived 2006-12-02 at the Wayback Machine

- S2CID 97905966.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33438-2.

- ^ "ISO 13500:2008 Petroleum and natural gas industries — Drilling fluid materials — Specifications and tests". ISO. 2008. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ISBN 9780195106916.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under Public domain. Text taken from Barite Statistics and Information, National Minerals Information Center, U.S. Geological Survey.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under Public domain. Text taken from Barite Statistics and Information, National Minerals Information Center, U.S. Geological Survey.

- ^ a b c M. Michael Miller Barite, 2009 Minerals Yearbook

- ^ "Barite: The mineral Barite information and pictures". www.minerals.net. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- ^ S2CID 40823176.

- ^ "Monograph on Barytes". Indian Bureau of Mines. 1995. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ^ "Definition of blanc fixe". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- .

- ^ Ben Bulben. Mhti.com. Retrieved on 2011-05-05.

- .

- ^ Muirshiel Mine. Clyde Muirshiel Regional Park. Scotland.

- ^ "Production of barite worldwide 2019". Statista. Retrieved 2020-08-30.

- ^ a b "The Barytes Association, Barytes Statistics". Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2015-05-11.

- S2CID 129874363.

- .

- ISSN 2500-0632.

- PMID 10097047.

- ^ a b Grasty, Robert L.; Smith, Charles; Franklin, James M.; Jonasson, Ian R. (1988-09-01). "Radioactive orphans in barite-rich chimneys, Axial Caldera, Juan De Fuca Ridge". The Canadian Mineralogist. 26 (3): 627–636.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 129020357.

- ^ ISBN 978-4-431-54864-5

- ^ S2CID 248614826.

- ISBN 1847734847

Further reading

- Johnson, Craig A.; Piatak, Nadine M.; Miller, M. Michael; Schulz, Klaus J.; DeYoung, John H.; Seal, Robert R.; Bradley, Dwight C. (2017). "Barite (Barium). Chapter D of: Critical Mineral Resources of the United States—Economic and Environmental Geology and Prospects for Future Supply. Professional Paper 1802–D". U.S. Geological Survey Professional Papers. doi:10.3133/pp1802D.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Barite (PDF). United States Geological Survey.

This article incorporates public domain material from Barite (PDF). United States Geological Survey.