Batavian Revolution

| Batavian Revolution | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Atlantic Revolutions | |||

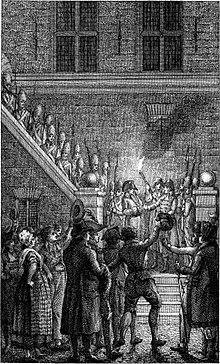

Patriot troops, 18 January 1795. | |||

| Date | 1781–1795 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by | Authoritarianism of William V | ||

| Goals |

| ||

| Resulted in | Batavian Republic established | ||

| Parties | |||

| Lead figures | |||

| History of the Netherlands |

|---|

|

|

|

The Batavian Revolution (Dutch: De Bataafse Revolutie) was a time of political, social and cultural turmoil at the end of the 18th century that marked the end of the Dutch Republic and saw the proclamation of the Batavian Republic.

The initial period, from about 1780 to 1787, is known as the

Orangists

to power with little fighting.

But after the

Napoleon Bonaparte

.

Background

By the end of the 18th century, the Netherlands found themselves in a deep economic crisis, caused by the devastating

Joan van der Capellen tot den Pol

, who were seeking to reduce the amount of power held by the stadtholder.

Thus, a division emerged between the

Guelders and Utrecht

(outside of its capital city).

In 1785, stadtholder

Duke of Brunswick crossed the border. The fortress of Vianen was deserted, and the city of Utrecht opened its gates. At the fortress of Woerden preparations for defense were made, but there was no actual resistance when the Prussians arrived. In Amsterdam several houses of patriot regents were plundered by mobs. The stadholder returned to The Hague

, and Amsterdam, the last city to hold out, surrendered on October 10.

The Patriots continued urging citizens to resist the government by distributing pamphlets, creating "Patriot Clubs" and holding public

Grand Pensionary Laurens Pieter van de Spiegel

.

Proclamation of the Republic

The restoration was temporary, however. Only two years later, the

Charles Pichegru, with a Dutch contingent under general Herman Willem Daendels, crossed the great frozen rivers that traditionally protected the Netherlands from invasion. Aided by the fact that a substantial proportion of the Dutch population looked favourably upon the French incursion, and often considered it a liberation,[5][full citation needed] the French were quickly able to break the resistance of the forces of the Stadtholder, and his Austrian and British allies. However, in many cities revolution broke out even before the French arrived and Revolutionary Committees took over the city governments, and (provisionally) the national government also. The States of Holland and West Friesland, for instance, were abolished and replaced with the Provisional Representatives of the People of Holland.[6]

Aftermath

The Batavian Revolution ended with the proclamation of the

Napoleon's brother, Louis Napoleon as King of Holland. In 1810, the area was annexed into the First French Empire. In 1813, the Netherlands regained their independence, with William's son William Frederick

as sovereign prince.

See also

References

- Schama, Simon, Patriots and Liberators: Revolution in the Netherlands 1780–1813, 1977

- De Vries, Jan and Ad van der Woude, The First Modern Economy: Success, Failure, and Perseverance of the Dutch Economy, 1500-1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997

External links

- Danielle Aucoin. The Dutch Patriot Revolution 1780 – 1787:Continuity or Change?

- The Patriots, 1787

- The Prussian Invasion of the Netherlands in 1787

Further reading

- Klein, S.R.E. (1995) Patriots Republikanisme. Politieke cultuur in Nederland (1766-1787).

- Leeb, I.L. (1973) The Ideological Origins of the Batavian Revolution.

- Verweij, G. (1996) Geschiedenis van Nederland. Levensverhaal van zijn bevolking.