Battle of the Eurymedon (190 BC)

| Battle of the Eurymedon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman–Seleucid War | |||||||

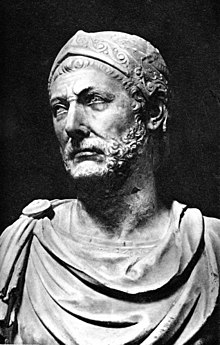

A marble bust, reputedly of Hannibal | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Rhodes | Seleucid Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Eudamus Pamphilidas Charikleitos |

Hannibal Apollonius | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 38 ships | 47 ships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 10 ships damaged |

1 ship seized 20 ships damaged | ||||||

Approximate location of the Battle of Eurymedon | |||||||

The Battle of the Eurymedon, also known as the Battle of Side took place in August 190 BC. It was fought as part of the

The battle took place off

Background

Following his return from his Bactrian (210–209 BC)

In late winter 196/195, Rome's erstwhile chief enemy, Carthaginian general Hannibal, fled from Carthage to Antiochus' court in Ephesus. Despite the emergence of pro-war party led by Scipio Africanus, the Roman Senate exercised restraint. The Seleucids expanded their holdings in Thrace from Perinthus to Maroneia at the expense of Thracian tribesmen. Negotiations between the Romans and the Seleucids resumed, coming to a standstill once again, over differences between Greek and Roman law on the status of disputed territorial possessions. In the summer of 193, a representative of the Aetolian League assured Antiochus that the Aetolians would take his side in a future war with Rome, while Antiochus gave tacit support to Hannibal's plans of launching an anti-Roman coup d'état in Carthage.[6] The Aetolians began spurring Greek states to jointly revolt under Antiochus' leadership against the Romans, hoping to provoke a war between the two parties. The Aetolians then captured the strategically important port city of Demetrias, killing the key members of the local pro-Roman faction. In September 192, Aetolian general Thoantas arrived at Antiochus' court, convincing him to openly oppose the Romans in Greece. The Seleucids selected 10,000 infantry, 500 cavalry, 6 war elephants and 300 ships to be transferred for their campaign in Greece.[7]

Prelude

The Seleucid fleet sailed via

The Romans intended to invade the Seleucid base of operations in Asia Minor which could only be done by crossing the Aegean Sea, the Hellespont being the preferable option due to logistical concerns. Antiochus saw his fleet as disposable, believing that he could still rout the Romans on land. His adversaries on the other hand, could not afford a major defeat at sea, since the manpower to commandeer a new fleet would not be available for months; all while the Roman infantry would struggle to sustain itself, while remaining grounded in mainland Greece.[11] Both sides began hastily reequipping their navies, constructing new warships and drafting seamen.[12] A Roman naval force under Gaius Livius Salinator consisting of 81 ships arrived at the Piraeus too late to impact the campaign in mainland Greece. It was therefore dispatched to the Thracian coast, where it was to unite with the navies of the Rhodians and the Attalids. The Seleucids attempted to intercept the Roman fleet before this could be achieved. In September 191, the Roman fleet defeated the Seleucids in the Battle of Corycus, enabling it to take control of several cities including Dardanus and Sestos on the Hellespont.[13]

Following the Battle of Corycus, the Roman–

Battle

In July 190, Hannibal ordered his fleet of three

Hannibal's fleet assumed battle formation first, with Hannibal leading the seaward wing while Seleucid nobleman Apollonius commanded the landward wing. Eudamus commanded the Rhodian seaward wing, Pamphilidas led the center and Charikleitos commanded the landward wing.

Aftermath

Hannibal had preserved most of his fleet, however he was in no position to unite with Polyxenidas' fleet at Ephesus since his ships required lengthy repairs.[28] Polyxenidas thus found himself isolated, as he was unable to face the Romans at sea without significant reinforcements. The Rhodians withdrew to Rhodes for repairs, leaving Charikleitos with 20 ships at Megiste.[29] In September, when Aemilius dispatched a part of his fleet to the Hellespont in order to assist the Roman army in its invasion of Asia Minor, Polyxenidas seized the opportunity to attack the Romans at sea.[28] The ensuing Battle of Myonessus resulted in a decisive Roman-Rhodian victory, which solidified Roman control over the Aegean Sea, enabling them to launch an invasion of Seleucid Asia Minor.[30] Antiochus withdrew his armies from Thrace, while simultaneously offering to cover half of the Roman war expenses and accept the demands made in Lysimachia in 196. Yet the Romans were determined to crush the Seleucids once and for all.[30] As the Roman forces reached Maroneia, Antiochus began preparing for a final decisive battle.[31]

References

- ^ Lerner 1999, pp. 45–48.

- ^ Overtoom 2020, p. 147.

- ^ Sartre 2006, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Sartre 2006, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 60–62.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, p. 64.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Graigner 2002, pp. 279–281.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Graigner 2002, pp. 37.

- ^ Graigner 2002, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, p. 74.

- ^ Graigner 2002, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Taylor 2013, p. 141.

- ^ Graigner 2002, pp. 296–297.

- ^ a b Graigner 2002, p. 297.

- ^ Taylor 2013, p. 142.

- ^ Graigner 2002, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, p. 76.

- ^ a b Graigner 2002, p. 299.

- ^ Sarikakis 1974, pp. 76–77.

- ^ a b Graigner 2002, p. 300.

- ^ Lazenby 1987, pp. 169–170.

- ^ a b Sarikakis 1974, p. 77.

- ^ Graigner 2002, pp. 300–301.

- ^ a b Sarikakis 1974, p. 78.

- ^ Graigner 2002, p. 307.

Sources

- Graigner, John (2002). The Roman War of Antiochus the Great. Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004128408.

- Lazenby, John (1987). "The Diekplous". Greece & Rome. 34 (2): 169–177. JSTOR 642944. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- Lerner, Jeffrey (1999). The Impact of Seleucid Decline on the Eastern Iranian Plateau: The Foundations of Arsacid Parthia and Graeco-Bactria. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 9783515074179.

- Overtoom, Nikolaus Leo (2020). Reign of Arrows: The Rise of the Parthian Empire in the Hellenistic Middle East. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190888329.

- Sarikakis, Theodoros (1974). "Το Βασίλειο των Σελευκιδών και η Ρώμη" [The Seleucid Kingdom and Rome]. In Christopoulos, Georgios A. & Bastias, Ioannis K. (eds.). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος Ε΄: Ελληνιστικοί Χρόνοι [History of the Greek Nation, Volume V: Hellenistic Period] (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. pp. 55–91. ISBN 978-960-213-101-5.

- Sartre, Maurice (2006). Ελληνιστική Μικρασία: Aπο το Αιγαίο ως τον Καύκασο [Hellenistic Asia Minor: From the Aegean to the Caucaus] (in Greek). Athens: Patakis Editions. ISBN 9789601617565.

- Taylor, Michael (2013). Antiochus The Great. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 9781848844636.