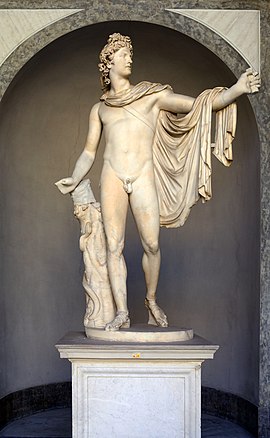

Apollo Belvedere

| Apollo Belvedere | |

|---|---|

| |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Artist | After Leochares |

| Year | c. AD 120–140 |

| Type | White marble |

| Dimensions | 224 cm (88 in) |

| Location | Vatican Museums, Vatican City |

| 41°54′23″N 12°27′16″E / 41.906389°N 12.454444°E | |

The Apollo Belvedere (also called the Belvedere Apollo, Apollo of the Belvedere, or Pythian Apollo)[1] is a celebrated marble sculpture from classical antiquity.

The work has been dated to mid-way through the 2nd century A.D. and is considered to be a Roman copy of an original bronze statue created between 330 and 320 B.C. by the Greek sculptor

From the mid-18th century it was considered the greatest ancient sculpture by ardent neoclassicists, and for centuries it epitomized the ideals of aesthetic perfection for Europeans and westernized parts of the world.

Description

The Greek god Apollo is depicted as a standing archer having just shot an arrow. Although there is no agreement as to the precise narrative detail being depicted, the conventional view has been that he has just slain the serpent Python, the chthonic serpent guarding Delphi—making the sculpture a Pythian Apollo. Alternatively, it may be the slaying of the giant Tityos, who threatened his mother Leto, or the episode of the Niobids.

The large white marble sculpture is 2.24 m (7.3 feet) high. Its complex

The lower part of the right arm and the left hand were missing when discovered and were restored by Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli (1507–1563), a sculptor and pupil of Michelangelo.

Modern reception

Renaissance

Before its installation in the Cortile delle Statue of the Belvedere palace in the

Once it was installed in the Cortile, however, it immediately became famous in artistic circles and a demand for copies of it arose. The Mantuan sculptor

In addition to Dürer, several major artists during the late Renaissance sketched the Apollo, including

18th century

The Apollo became one of the world's most celebrated art works when in 1755 it was championed by the German

19th century

The neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova adapted the work's fluency to his marble Perseus (Vatican Museums) in 1801.

The

Finally, starting something of a trend among some later commentators, the art critic

20th century

The critical reputation of the Apollo continued to decline in the 20th century, to the point of complete neglect. In 1969, a summary of its reception up to that point was provided by the

Influence

- Dürer, Albrecht, Adam and Eve (1504 engraving)

- Copies of the Apollo Belvedere appear as cultural props in Joshua Reynolds's Commodore Augustus Keppel (1752-3, oil on canvas) and Jane Fleming, later Countess of Harrington (1778–79, oil on canvas).

- Canova, Antonio, Perseus (1801, Vatican Museums, 180x, Metropolitan Museum of Art)

- In Byron describes how the statue requites humanity's debt to Prometheus: "And if it be Prometheus stole from Heaven / The fire which we endure, it was repaid / By him to whom the energy was given / Which this poetic marble hath array'd / With an eternal glory—which, if made / By human hands, is not of human thought; / And Time himself hath hallowed it, nor laid / One ringlet in the dust—nor hath it caught / A tinge of years, but breathes the flame with which 'twas wrought." (IV, CLXIII, 161–163; 1459–67).

- Boston Athenaeum, later Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

- Apollo tended by the Nymphs of Thetis

- The head of the Apollo Belvedere is featured prominently in The Song of Love, a 1914 painting by Giorgio de Chirico

- The Sower by Jean-François Millet (1850) is influenced by the Apollo Belvedere in the treatment and pose of the figure in the piece. The pose of the figure is linked to the sculpture as Millet was attempting to heroise the peasant that he was depicting.

- The Minute Man by Daniel Chester French, 1874 at the Old North Bridge in Concord, Massachusetts[11]

- In Robert Musil's 1943 novel The Man Without Qualities, the character Ulrich comments "Who still needed the Apollo Belvedere when he had the new forms of a turbodynamo or the rhythmic movements of a steam engine's pistons before his eyes!" [12]

- In her poem "In the Days of Prismatic Color", Marianne Moore writes that "Truth is no Apollo/ Belvedere, no formal thing."[13]

- Arthur Schopenhauer in the third book of The World as Will and Representation (1859) refers to the head of the Apollo Belvedere, admiring it for the way it exhibits human superiority: "The head of the god of the Muses, with eyes far afield, stands so freely on the shoulders that it seems to be wholly delivered from the body, and no longer subjects to its cares."

- Alexander Pushkin refers to Apollo Belvedere in his 1829 poem The Poet and the Crowd ("Поэт и толпа").

- Varden, a character in Dorothy L. Sayers's The Abominable History of the Man with Copper Fingers recounts how he portrayed Apollo in a movie as "a statue that's brought to life ... You couldn't find an atom of offence from beginning to end, it was all so tasteful, though in the first part one didn't have anything to wear except a sort of scarf—taken from the classical statue, you know." One of his audience, a man with a classical education, guesses from the scarf that the actor was speaking of Apollo Belvedere.

- A bust of Apollo Belvedere is a prominent feature of Charles Bird King's 1835 still life The Vanity of the Artist's Dream, which depicts the struggle of classically trained artists to be relevant in the 19th century.

References

Citations

- ^ Réveil, Etienne Achille and Jean Duchesne (1828), Museum of Painting and Sculpture, or Collection of the Principal Pictures, Statues and Bas-Reliefs, in the Public and Private Galleries of Europe, London: Bossanage, Bartes and Lowell, Vol 11, p. 126. ("The Pythian Apollo, called the Belvedere Apollo")

- ^ "Belvedere Apollo". Vatican Museums. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 2023-08-20.

- ^ Paolo Prignani (25 June 2015). "L'Apollo del Belvedere, on CambiaVersoAnzio". cambiaversoanzio.wordpress.com (in Italian). Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ^ Roberto Weiss, The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity (Oxford University Press) 1969:103 first noted the entries in 1489 and a repetition in 1493 in the somewhat chaotic Cesena chronicle of Giuliano Fantaguzzi.

- ^ H. H. Brummer, The Statue Court in the Vatican Belvedere (Stockholm) 1970:44–71, which gives the most concise review of the statue's discovery and its history.

- ^ Weiss 1969:103.

- ^ Deborah Brown, "The Apollo Belvedere and the Garden of Giuliano della Rovere at SS. Apostoli" Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 49 (1986), pp. 235–238.

- ^ a b Barkan, Op. cit., pg 56.

- ^ Gregory Curtis, Disarmed, (New York: Knopf, 2003) pp. 57–61.

- Harper & Row, Publishers, pg 2.

- ^ Roland Wells Robbins, The Story of the Minute Man, (Stoneham, MA: George R. Barnstead & Son, 1945) pp. 13–24.

- ^ Robert Musil, The Man Without Qualities vol. 1, (New York: Vintage Books, 1995): 33.

- ^ Marianne Moore, "In the Days of Prismatic Color," The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore (New York: Penguin, 1994): 42.

Other sources

- Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, 1981. Taste and the Antique (Yale University Press) Cat. no. 8. Critical history of the Apollo Belvedere.

External links

- Entry in the Census of Antique Works of Art and Architecture Known in the Renaissance

- Image of Apollo Belvedere with a fig leaf

- The sculpture shown with and without a fig leaf

- 16th-century engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi

- "Comparing Different Artists – The Apollo Belvedere"

- See also the gold medal of the Apollo Belvedere of the Vatican Museums.

- Apollo Belvedere in the Census database

- L'Apollo del Belvedere: article in the website Cambiaversoanzio (italian)

Media related to Apollo Belvedere at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Apollo Belvedere at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Venanzo Crocetti Museum |

Landmarks of Rome Apollo Belvedere |

Succeeded by Augustus of Prima Porta |