Ben Linder

The article's lead section may need to be rewritten. (November 2023) |

Ben Linder | |

|---|---|

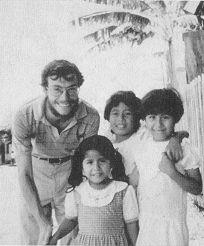

Linder with Nicaraguan children | |

| Born | July 7, 1959 |

| Died | April 28, 1987 (aged 27) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Known for | Electrification work in rural Nicaragua, murdered while working on a hydroelectric facility near El Cuá[1] |

Benjamin Ernest "Ben" Linder (July 7, 1959 – April 28, 1987), was an American engineer. While working on a small

, a loose confederation of rebel groups funded by the U.S. government.The autopsy report stated that Linder had gunshot wounds to the back of the legs (indicating he had his back to the killers) , while on the ground he suffered multiple wounds to his face ( the coroner noted: as from an ice pick) and died from a close range gunshot to the head. The other two men were also executed in the same way. It is unknown if they were similarly tortured first. There was no mention in Linder’s autopsy report of grenade fragments.

Coming at a time when U.S. support for the Contras was already highly controversial, Linder's death made front-page headlines around the world and further polarized opinion in the United States.

Biography

The

Linder felt inspired by the 1979 Sandinista revolution, and wanted to support its efforts to improve the lives of the country's poorest people. The Reagan administration, however, was determined to cripple the revolution. Beginning in 1981, the Central Intelligence Agency secretly trained, armed and supplied thousands of Contra rebels. A major element of the Contras' strategy was to launch attacks on government cooperatives, health clinics and power stations—the things that most exemplified the improvements that had been brought about by the revolution.

In 1986, Linder moved from Managua to El Cuá, a village in the Nicaraguan war zone, where he helped form a team to build a hydroelectric plant to bring electricity to the town. While living in El Cuá, he participated in vaccination campaigns, using his talents as a clown, juggler, and unicyclist to entertain the local children, for whom he expressed great affection and concern.

On 28 April 1987, Linder and two Nicaraguans were killed in a Contra ambush while traveling through the forest to scout out a construction site for a new dam for the nearby village of San José de Bocay. The autopsy showed that Linder had been wounded by a grenade, then shot at point-blank range in the head. The two Nicaraguans—Sergio Hernández and Pablo Rosales—were also killed at close range. Linder was posthumously awarded the Courage of Conscience award[2] on September 26, 1992.

Controversy

Linder's death quickly inflamed the already-polarized debate inside the United States, with opponents of U.S. policy decrying the use of taxpayers' dollars to finance the killing of an American citizen as well as thousands of Nicaraguan civilians.

The administration fought back, with

Linder's mother Elisabeth, in Nicaragua for her son's funeral, said,

My son was brutally murdered for bringing electricity to a few poor people in northern Nicaragua. He was murdered because he had a dream and because he had the courage to make that dream come true. ... Ben told me the first year that he was here, and this is a quote, "It's a wonderful feeling to work in a country where the government's first concern is for its people, for all of its people."[3]

During a Congressional hearing in May 1987, some defenders of U.S. policy in Nicaragua responded, launching personal attacks on Linder's family and other witnesses. The

The death of Linder, coming as Congressional hearings investigated the

In July 1996, American journalist

The song "

See also

- Witness for Peace

- Bill Stewart, an ABCreporter killed along with his interpreter in Managua in 1979.

- Brian Willson, an American injured by a naval munitions train while protesting US arms shipments to Central America.

Footnotes

- ^ Blood of Brothers, page 328; Kinzer

- ^ The Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience Recipients List Archived February 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gary Handschumacher, "Mourn Ben Linder, Not His Killer: Ronald Reagan's Death Squads," Counterpunch, June 16, 2004.

- ^ ABROAD AT HOME; 'The Most Cruel' By Anthony Lewis, May 15, 1987

- ^ See: Paul Berman, "In Search of Ben Linder's Killers," The New Yorker, vol. 72, no. 28 (Sept. 23, 1996), pp. 58-??.

- ^ See: Joan Kruckewitt, The Death of Ben Linder. Seven Stories Press 2001.

- ^ "Sting: Fragile CD," Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine www.sting.com/

- ^ Kunzle, David (1995). The Murals of Revolutionary Nicaragua, 1979-1992. California: University of California Press. p. 83.

Further reading

- Héctor Perla, Jr., "Heirs of Sandino: The Nicaraguan Revolution and the U.S.-Nicaragua Solidarity Movement," Latin American Perspectives, vol. 36, no. 6 (Nov. 2009), pp. 80–100. In JSTOR

External links

- Remembering Benjamin Linder by Jeffrey McCrary

- The Death of a Dreamer, from the Religious Task Force on Central America and Mexico

- Publisher's webpage for The Death of Ben Linder, by Joan Kruckewitt ISBN 1-58322-068-2

- The Death of Ben Linder (excerpt)

- Ben Linder explains the functions of the small scale hydro-electric facility in El Cuá, Nicaragua requires RealAudio

- Photo gallery of Ben Linder as a unicyclist Archived 2008-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Casa Ben Linder, is a meeting place and has served as an "incubator" for solidarity organizations in Nicaragua

- Ben Linder info at Marc Becker's website

- The Linder House Co-op at the University of Michigan.

- Film by Jason Blalock. Interviews with Ben Linder's American and Nicaraguan coworkers 20 years later

- El Payaso, obra de teatro de Emilio Rodríguez, dirigido por Georgina Escobar, presentado at Teatro Milagro, Portland Guía de estudio

- El Payaso, by Emilio Rodríguez, directed by Georgina Escobar, at Teatro Milagro, Portland. English Press Release