Bengali Muslims

বাঙালি মুসলমান | |

|---|---|

South Asian Muslims |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Bengalis |

|---|

|

Bengali Muslims (Bengali: বাঙালি মুসলমান; pronounced [baŋali musɔlman])[15][16] are adherents of Islam who ethnically, linguistically and genealogically identify as Bengalis. Comprising about two-thirds of the global Bengali population, they are the second-largest ethnic group among Muslims after Arabs.[17][18] Bengali Muslims make up the majority of Bangladesh's citizens, and are the largest minority in the Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura and Assam.[19]

They speak or identify the

The Bengal region was a supreme power of the medieval Islamic East.[20] European traders identified the Bengal Sultanate as "the richest country to trade with".[21] Bengal viceroy Muhammad Azam Shah assumed the imperial throne. Mughal Bengal became increasingly independent under the Nawabs of Bengal in the 18th century.[22]

The Bengali Muslim population emerged as a synthesis of Islamic and Bengali cultures. After the Partition of India in 1947, they comprised the demographic majority of Pakistan until the independence of East Pakistan (historic East Bengal) as Bangladesh in 1971.

Identity

A

The majority of Bengali Muslims are

History

Pre-Islamic history

Rice-cultivating communities existed in Bengal since the second millennium BCE. The region was home to a large agriculturalist population, marginally influenced by

Early explorers

The spread of Islam in the Indian subcontinent can be a contested issue.[29] Historical evidences suggest the early Muslim traders and merchants visited Bengal while traversing the Silk Road in the first millennium. One of the earliest mosques in South Asia is under excavation in northern Bangladesh, indicating the presence of Muslims in the area around the lifetime of Muhammad.[30] Starting in the 9th century, Muslim merchants increased trade with Bengali seaports.[31] Islam first appeared in Bengal during Pala rule, as a result of increased trade between Bengal and the Arab Abbasid Caliphate.[32] Coins of the Abbasid Caliphate have been discovered in many parts of the region.[33] The people of Samatata, in southeastern Bengal, during the 10th-century were of various religious backgrounds. During this time, Arab geographer Al-Masudi, who authored The Meadows of Gold, travelled to the region and noticed a Muslim community of inhabitants.[34]

In addition to trade, Islam was also being introduced to the people of Bengal through the migration of Sufi missionaries prior to conquest. The earliest known Sufi missionaries were Syed Shah Surkhul Antia and his students, most notably Shah Sultan Rumi, in the 11th century. Rumi settled in present-day Netrokona, Mymensingh where he influenced the local ruler and population to embrace Islam.

Early Islamic kingdoms

While Bengal was under the

Sultanate of Bengal

The establishment of a single united

The Bengal Sultanate was a melting pot of Muslim political, mercantile and military elites. During the 14th century, Islamic kingdoms stretched from

The Bengal Sultanate was ruled by five dynastic periods, with each period have a particular ethnic identity. The Ilyas Shahi dynasty was of

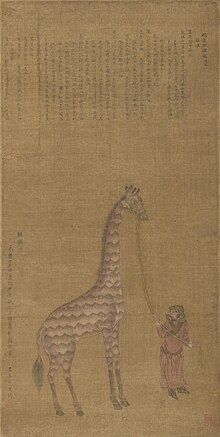

During the independent sultanate period, Bengal forged strong diplomatic relations with empires outside the subcontinent. The most notable of these relationships was with

Conquests and vassal states

Soon after its creation, the Bengal Sultanate sent the first Muslim army into Nepal. Its forces reached as far as Varanasi while pursuing a retreating Delhi Sultan.[51][52]

The Bengal Sultanate also counted Tripura as a vassal state. Bengal restored the throne of Tripura by helping

Maritime trade

Bengali ships dominated the

The Chinese Muslim envoy

Mughal period

The

The process of Islamization of eastern Bengal, now Bangladesh, is not fully understood due to limited documentation from the 1200s to 1600s, the period during which Islamization is believed to have occurred.[70] There are numerous theories about how Islam spread in region; however, the overwhelming evidence is strongly suggestive of a gradual transition of the local population from Buddhism, Hinduism and other indigenous religions to Islam starting in the thirteenth century facilitated by Sufi missionaries (such as Shah Jalal in Sylhet for example) and later by Mughal agricultural reforms centered around Sufi missions [71]

The factors facilitating conversion to Islam from Buddhism, Hinduism and indigenous religions, again is not fully understood. Lack of primary sources from that era have resulted in various hypotheses.

Centuries prior to the advent of Islam into the region, Bengal was a major center of Buddhism on the Indian Subcontinent.

A few centuries later the

This made East Bengal a thriving melting pot with strong trade and cultural networks. It was the most prosperous part of the subcontinent.[78][80] East Bengal became the center of the Muslim population in the eastern subcontinent and corresponds to modern-day Bangladesh.[79]

Ancestry

According to the 1881 Census of Bengal, Muslims constituted a bare majority of the population of Bengal proper (50.2 percent compared with the Hindus at 48.5 percent). However, in the eastern part of Bengal, Muslims were thick on the ground. The proportions of Muslims in Rajshahi, Dhaka and Chittagong divisions were 63.2, 63.6 and 67.9 percent respectively. The debate draws on the writings of some late nineteenth-century authors, but in its current form was initially formulated in 1963 by M.A. Rahim. Rahim suggested that a significant proportion of Bengal's Muslims were not Hindu converts but were descendants of 'aristocratic' immigrants from various parts of the Muslim world. Specifically, he estimated that in 1770, of about 10.6 million Muslims in Bengal, 3.3 million (about 30 percent) had 'foreign blood'.

British colonial period

The Bengal region was

After 1870, Muslims began a seeking British-style education in increasingly larger numbers. Under the leadership of

Eastern Bengal and Assam (1905-1912)

A precursor to the modern state of Bangladesh was the province of

During the short lifespan of the province, school enrollment increased by 20%. New subjects were introduced into the college curriculum, including Persian, Sanskrit, mathematics, history and algebra. All towns became connected by an inter-district road network. The population of the capital city Dacca rose by 21% between 1906 and 1911.[91]

1947 Partition and Bangladesh

An important moment in the history of Bengali self-determination was the Lahore Resolution in 1940, which was promoted by politician A. K. Fazlul Huq. The resolution initially called for the creation of a sovereign state in the "Eastern Zone" of British India.[92] However, its text was later changed by the top leadership of the Muslim League. The Prime Minister of Bengal Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy proposed an independent, undivided, sovereign "Free State of Bengal" in 1947.[93] Despite calls from liberal Bengali Muslim League leaders for an independent United Bengal, the British government moved forward with the Partition of Bengal in 1947. The Radcliffe Line made East Bengal a part of the Dominion of Pakistan. It was later renamed as East Pakistan, with Dhaka as its capital.

The

Sir

Bangladesh was founded as a secular Muslim majority nation.

Science and technology

Historical Islamic kingdoms that existed in Bengal employed several clever technologies in numerous areas such as architecture, agriculture, civil engineering, water management, etc. The creation of canals and reservoirs was a common practice for the sultanate. New methods of irrigation were pioneered by the Sufis. Bengali mosque architecture featured terracotta, stone, wood and bamboo, with curved roofs, corner towers and multiple domes. During the Bengal Sultanate, a distinct regional style flourished which featured no minarets, but had richly designed mihrabs and minbars as niches.[100]

Islamic Bengal had a long history of textile weaving, including export of muslin during the 17th and 18th centuries. Today, the weaving of Jamdani is classified by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage.[101][102]

Modern science was begun in Bengal during the period of British colonial rule. Railways were introduced in 1862, making Bengal one of the earliest regions in the world to have a rail network.

In the second half of the 20th century, the Bengali Muslim American Fazlur Rahman Khan became one of the most important structural engineers in the world, helping design the world's tallest buildings.[105] Another Bengali Muslim German-American, Jawed Karim, was the co-founder of YouTube.[106]

In 2016, the modernist Bait-ur-Rouf Mosque, inspired by the Bengal Sultanate-style of buildings, won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture.[107]

Demographics

Bengali Muslims constitute the world's second-largest Muslim ethnicity (after the Arab world) and the largest Muslim community in South Asia.

A large Bengali Muslim diaspora is found in the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, which are home to several million expatriate workers from South Asia. A more well-established diaspora also resides in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Pakistan. The first Bengali Muslim settlers in the United States were ship jumpers who settled in Harlem, New York and Baltimore, Maryland in the 1920s and 1930s.[118]

Culture

Surnames

Surnames in Bengali Muslim society reflect the region's cosmopolitan history. They are mainly of

Art

Zainul Abedin, who's better known as Shilpacharya (Master of Art) was a prominent painter. His famine sketches of the 1940s are his most remarkable works of all time.

The unique trend of

The

The weaving industry of Bengal has prospered with the help of the Muslims natives. The Bengali origin Jamdani is believed to be a fusion of the ancient cloth-making techniques of Bengal with the muslins produced by Bengali Muslims since the 14th century. Jamdani is the most expensive product of traditional Bengali looms since it requires the most lengthy and dedicated work. The traditional art of weaving jamdani was declared a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2013[121][122][123] and Bangladesh received geographical indication (GI) status for Jamdani Sari in 2016.

Sheikh Zainuddin was a prominent Bengali Muslim artist in the 18th century during the colonial period. His works were inspired by the style of Mughal courts.[124]

Architecture

An indigenous style of Islamic architecture flourished in Bengal during the medieval Sultanate period.

The

Sufism

Syncretism

As part of the conversion process, a syncretic version of mystical Sufi Islam was historically prevalent in medieval and early modern Bengal. The Islamic concept of tawhid was diluted into the veneration of Hindu folk deities, who were now regarded as pirs.[127] Folk deities such as Shitala (goddess of smallpox) and Oladevi (goddess of cholera) were worshipped as pirs among certain sections of Muslim society.[23]

Language

Bengali Muslims maintain their indigenous language with its native

Bengali evolved as the most easterly branch of the Indo-European languages.[citation needed] The Bengal Sultanate promoted the literary development of Bengali over Sanskrit, apparently to solidify their political legitimacy among the local populace. Bengali was the primary vernacular language of the Sultanate.[129] Bengali borrowed a considerable amount of vocabulary from Arabic and Persian. Under the Mughal Empire, considerable autonomy was enjoyed in the Bengali literary sphere.[130][131] The Bengali Language Movement of 1952 was a key part of East Pakistan's nationalist movement. It is commemorated annually by UNESCO as International Mother Language Day on 21 February.

Literature

While proto-Bengali emerged during the pre-Islamic period, the Bengali literary tradition crystallised during the Islamic period. As Persian and Arabic were prestige languages, they significantly influenced

Bengal was also a major center of Persian literature. Several newspapers and thousands of books, documents and manuscripts were published in Persian for 600 years. The Persian poet Hafez dedicated an ode to the literature of Bengal while corresponding with Sultan Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah.[136]

The first Bengali Muslim novelist was

Literary societies

- Kendriyo Muslim Sahitya Sangsad[139]

- Muslim Sahitya-Samaj[140]

- Bangiya Mussalman Sahitya Samiti[141]

- Bangiya Sahitya Bisayini Mussalman Samiti[142]

- Mohammedan Literary Society[143]

- Purba Pakistan Sahitya Sangsad[144]

- Pakistan Sahitya Sangsad, 1952[145]

- Uttar Banga Sahitya Sammilani[146]

- Rangapur Sahitya Parisad[147]

Literary magazines

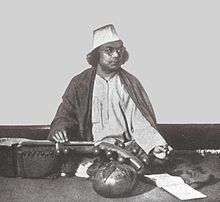

Music

A notable feature of Bengali Muslim music is the syncretic

In the field of modern music Runa Laila became widely acclaimed for her musical talents across South Asia.[150]

Cuisine

The Mughal influence in Bengali Cuisine led to a increase in the use of milk and sugar in sweet dishes like

Festivals

Bishwa Ijtema

The

Leadership

There is no single governing body for the Bengali Muslim community, nor a single authority with responsibility for religious doctrine. However, the semi-autonomous

The clergy of the Bengali Muslim

Notable individuals

See also

Other Bengali religious groups

References

- ISBN 978-1-84774-052-6.

Bengali-speaking Muslims as a group consists of around 200 million people.

- ^ "Religions in Bangladesh | PEW-GRF". Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ a b

- Ghosal, Jayanta (19 April 2021). "Decoding the Muslim vote in West Bengal". India Today. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- "West Bengal Population 2021". Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- hajarduar (22 October 2013). "The curious case of the Surjapuri people". আলাল ও দুলাল | Alal O Dulal. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ a b

- PTI (10 February 2020). "Assam plans survey to identify indigenous Muslim population". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- Hazarika, Myithili (12 February 2020). "BJP wants to segregate Assamese Muslims from Bangladeshi Muslims, but some ask how". ThePrint. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "'Not cows to be milked' — Muslims in Bengal, Kerala, Assam are now assertive, want recognition". ThePrint. 7 April 2021. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Bhattacharya, Abhik (26 October 2022). "Museum To Display 'Miya' Culture In Assam Sealed, CM Says Only 'Lungi' Belongs To Them". Outlook.

- ^ "Explained: Why religious fault lines are emerging in Tripura". scroll.in. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ "Stateless and helpless: The plight of ethnic Bengalis in Pakistan". Al Jazeera. 29 September 2021. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

Ethnic Bengalis in Pakistan – an estimated two million – are the most discriminated ethnic community

- ^ Chaudhury, Dipanjan Roy. "Bengali-speaking Muslims languish in Pakistan". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

There are around three million Bengalis in Pakistan

- ^ "Microsoft Word — Cover_Kapiszewski.doc" (PDF). United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ "Labor Migration in the United Arab Emirates: Challenges and Responses". Migration Information Source. 18 September 2013. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ^ CT0341_2011 Census – Religion by ethnic group by main language – England and Wales ONS.

- ^ Snoj, Jure (18 December 2013). "Population of Qatar by nationality". Bqdoha.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ "Oman lifts bar on recruitment of Bangladeshi workers". News.webindia123.com. 10 December 2007. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Sarkar, Benoy Kumar (April 1941). "Bengali Culture as a System of Mutual Acculturations". Calcutta Review. Vol. LXXIX, no. 1. p. 10. [Mussalman also used in this work.]

- ^ Choudhury, A. K. (1984). The Independence of East Bengal: A Historical Process. A.K. Choudhury. [Mussalman also used in this work.]

- ISBN 978-1-4008-3138-8.

- ISBN 978-0822353188. Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ a b Andre, Aletta; Kumar, Abhimanyu (23 December 2016). "Protest poetry: Assam's Bengali Muslims take a stand". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ ISBN 9781317587460. Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ISBN 978-81-8069-149-2.

Bengal [...] was rich in the production and export of grain, salt, fruit, liquors and wines, precious metals, and ornaments besides the output of its handlooms in silk and cotton. Europe referred to Bengal as the richest country to trade with.

- ISBN 9789325993969– via Google Books.

- ^ ISBN 9780520205079. Archivedfrom the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 21 July 2016 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 9840690248. Archived(PDF) from the original on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ a b Mukhapadhay, Keshab (13 May 2005). "An interview with prof. Ahmed sharif". News from Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation". Pewforum.org. 9 August 2012. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ISBN 9780520205079. Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ "Bengali language". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ISBN 9789383419647. Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Ancient mosque unearthed in Bangladesh". Al Jazeera. 18 August 2012. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- OL 30677644M. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ISBN 978-81-7141-682-0.

- OL 30677644M. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ Al-Masudi, trans. Barbier de Meynard and Pavet de Courteille (1962). "1:155". In Pellat, Charles (ed.). Les Prairies d'or [Murūj al-dhahab] (in French). Paris: Société asiatique.

- OL 30677644M. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ Qurashi, Ishfaq (2012). "বুরহান উদ্দিন ও নূরউদ্দিন প্রসঙ্গ" [Burhan Uddin and Nooruddin]. শাহজালাল(রঃ) এবং শাহদাউদ কুরায়শী(রঃ) [Shah Jalal and Shah Dawud Qurayshi] (in Bengali).

- OL 30677644M. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- 'Abd al-Haqq al-Dehlawi. Akhbarul Akhyar.

- OL 30677644M. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ Hanif, N (2000). Biographical Encyclopaedia of Sufis: South Asia. Prabhat Kumar Sharma, for Sarup & Sons. p. 35.

- ^ "What is more significant, a contemporary Chinese traveler reported that although Persian was understood by some in the court, the language in universal use there was Bengali. This points to the waning, although certainly not yet the disappearance, of the sort of foreign mentality that the Muslim ruling class in Bengal had exhibited since its arrival over two centuries earlier. It also points to the survival, and now the triumph, of local Bengali culture at the highest level of official society." (Eaton 1993:60)

- ^ Rabbani, AKM Golam (7 November 2017). "Politics and Literary Activities in the Bengali Language during the Independent Sultanate of Bengal". Dhaka University Journal of Linguistics. 1 (1): 151–166. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017 – via www.banglajol.info.

- ISBN 978-0-520-24385-9. Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "Mint Towns". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ISBN 978-1-84511-381-0.

- ^ "Royalty, aesthetics and the story of mosques". The Daily Star. 17 May 2008. Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "African rulers of India: That part of our history we choose to forget". The Indian Express. 23 January 2022. Archived from the original on 28 July 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "The forgotten history of the African slaves who were brought to the Deccan and rose to great power". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ "Iliyas Shah". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ Tabori, Paul (1957). "Bridge, Bastion, or Gate". Bengali Literary Review. 3–5: 9–20.

- ^ ISBN 9788171021185. Archivedfrom the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9..

- ISBN 978-93-80607-20-7. Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

The Sri Rajmala indicates that the periodic invasions of Tripura by the Bengal sultans were part of the same strategy [to control the sub-Himalayan routes from the south-eastern delta]. Mines of coarse gold were found in Tripura.

- ISBN 978-1-84511-381-0.

[Husayn Shah] reduced the kingdoms of ... Tripura in the east to vassalage.

- ISBN 978-1-84511-381-0. [Ilyas Shah] extended his domain in every direction by defeating the local Hindu rajas (kings)—in the south to Jajnagar (Orissa).

- ISBN 978-1-139-50257-3.

- ISBN 978-1-84511-381-0. Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

[Husayn Shah pushed] its western frontier past Bihar up to Saran in Jaunpur ... when Sultan Husayn Shah Sharqi of Jaunpur fled to Bengal after being defeated in battle by Sultan Sikandar Lodhi of Delhi, the latter attacked Bengal in pursuit of the Jaunpur ruler. Unable to make any gains, Sikandar Lodhi returned home after concluding a peace treaty with the Bengal sultan.

- ^ "Kamata-Kamatapura". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Choudhury, Achyut Charan (1917). Srihattar Itibritta: Uttarrangsho শ্রীহট্রের ইতিবৃত্ত: উত্তরাংশ (in Bengali). Calcutta: Katha. p. 484 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Bangladesh Itihas Samiti, Sylhet: History and Heritage, (1999), p. 715

- ^ Sayed Mahmudul Hasan (1987). Muslim monuments of Bangladesh. Islamic Foundation Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Population Census of Bangladesh, 1974: District census report. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics Division, Ministry of Planning, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh. 1979. Archived from the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2006). The Delhi Sultanate, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, pp.215-20

- ISBN 978-0-521-22692-9.

- ISBN 978-93-80607-20-7. Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

some of them [items exported from Bengal to China] were probably re-exports. The Bengal ports possibly functioned as entrepots in Western routes in the trade with China.

- ^ Shoaib Daniyal. "Bengali New Year: how Akbar invented the modern Bengali calendar". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Chattopadhyay, Bhaskar (1988). Culture of Bengal: Through the Ages: Some Aspects. University of Burdwan. pp. 210–215.

- S2CID 55737704.

- ^ a b "The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760". publishing.cdlib.org. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d Rahman, Mahmadur (2019). The Dawn of Islam in Eastern Bengal. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 8–10. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019.

- ^ OCLC 133102415.

- ^ Harper, Francesca (12 May 2015). "The 1,000-year-old manuscript and the stories it tells". University of Cambridge. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ "Monumental Absence: The Destruction of Ancient Buddhist Sites". The Caravan. 9 July 2018. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4008-3138-8.

- ^ Alam, Muhammad Nur. "Agrarian Relations in Bengal: Ancient to British Period" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 October 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ a b Khandker, Hissam (31 July 2015). "Which India is claiming to have been colonised?". The Daily Star (Op-ed). Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ ISBN 9780520205079. Archivedfrom the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ISBN 9788131732021. Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- S2CID 144040355.

- ^ a b "Bengali Muslims and their identity: From fusion to confusion". The Daily Star. 5 April 2021. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- SBN 19-562203-0.

- (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2006). The Delhi Sultanate, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, pp.209–11

- ^ Taher, MA (2012). "Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ a b Khan, Muin-ud-Din Ahmed (2012). "Faraizi Movement". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8.

- ^ Kabir, Nurul (1 September 2013). "Colonialism, politics of language and partition of Bengal PART XV". New Age. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ "Eastern Bengal and Assam". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "Do we know anything about Lahore Resolution?". Al Arabiya. 24 March 2009. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ "Why did British prime minister Attlee think Bengal was going to be an independent country in 1947?". scroll.in. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-275-96832-8. Archivedfrom the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Harun-or-Rashid (2012). "Bangladesh Awami League". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-275-96832-8. Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-429-98176-0.

- ISBN 978-0-521-71377-1. Archivedfrom the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ "Bangladesh" (PDF). U.S. State Department. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-84511-381-0.

- ^ Muslin, Encyclopaedia Britannica, archived from the original on 4 May 2015, retrieved 2 June 2022

- ISBN 978-1-60901-535-0, archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2023, retrieved 21 December 2020

- ^ "History". Bangladesh Railway. Archived from the original on 15 November 2007. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "About BUET". BUET. Archived from the original on 29 September 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ^ a b "Fazlur R. Khan (American engineer)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ "Surprise! There's a third YouTube co-founder". USA Today. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ "China, Denmark projects among architecture award winners". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ "Understanding the Bengal Muslims Interpretative Essays Hardcover". Irfi.org. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ "Muslim Population by Country 2021". Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "Bengal beats India in Muslim growth rate". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ "Assamese Muslims plan 'mini NRC'". The Hindu. 10 April 2021. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2012. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- ^ "Muslim majority districts in Assam up". The Times of India. 26 August 2015. Archived from the original on 4 January 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ "Assam Muslim growth is higher in districts away from border". The Indian Express. 31 August 2015. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ "Census 2011 data rekindles 'demographic invasion' fear in Assam". Hindustan Times. 26 August 2015. Archived from the original on 4 January 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ "Tripura: Anti-Muslim violence flares up in Indian state". BBC News. 28 October 2021. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ISBN 9780313357244.

- ^ Dizikes, Peter (7 January 2013). "The hidden history of Bengali Harlem". MIT News Office. MIT. Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ "Art and Crafts". Banglapedia.

- ^ "Gazir Pat". Banglapedia.

- ^ "jamdani". britannica.com. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "Jamdani recognised as intangible cultural heritage by Unesco". The Daily Star. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "Traditional art of Jamdani weaving". UNESCO Culture Sector. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "Zainuddin, Sheikh". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-84511-381-0.

The Sultanate mosques ... all had in common a remarkable uniformity of design ... features familiar from the Islamic architecture of the central Islamic lands and north India reappear here; others are totally new.

- ^ "Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God". Abc-Clio.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ISBN 90-04-09497-0. Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Milam, William B. (4 July 2014). "The tangled web of history". Dhaka Tribune. Archived from the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-19-564173-8. Archivedfrom the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-7486-1436-3.

- ^ "BENGAL – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ a b c "The development of Bengali literature during Muslim rule" (PDF). Blogs.edgehill.ac.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Karim, Abdul (2012). "Nur Qutb Alam". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 18 July 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Rizvi, S.N.H. (1965). "East Pakistan District Gazetteers" (PDF). Government of East Pakistan Services and General Administration Department (1): 353. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Ahmed, Wakil (2012). "Sufi Literature". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ Billah, Abu Musa Mohammad Arif (2012). "Persian". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ Huq, Khondkar Serajul (2012). "Muslim Sahitya-Samaj". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ^ "Al Mahmud turns 75". The Daily Star. 13 July 2011. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ "Kendriyo Muslim Sahitya Sangsad". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Muslim Sahitya-Samaj". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Bangiya Mussalman Sahitya Samiti". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Bangiya Sahitya Bisayini Mussalman Samiti". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Mohammedan Literary Society". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Purba Pakistan Sahitya Sangsad". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Pakistan Sahitya Sangsad, 1952". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Uttar Banga Sahitya Sammilani". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Rangapur Sahitya Parisad". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Bangiya Mussalman Sahitya Patrika". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-19-513901-3. Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ Sharma, Devesh. "Beyond borders Runa Laila". Filmfare.com. Times Internet Limited. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ https://www.tbsnews.net/features/food/mughlai-cuisine-how-16th-century-empire-food-found-its-way-our-tables-293797?amp

- ^ "Muharram". Banglapedia.

- ^ 50th "Jashne Julus" to be held in Ctg tomorrow - The Daily Star https://www.thedailystar.net/news/bangladesh/news/50th-jashne-julus-be-held-ctg-tomorrow-3138246?amp

- ^ "Shab-e-Barat and Old Dhaka foods". The Daily Star. 1 June 2015.

- ^ "The Nobel Peace Prize for 2006". Nobel Foundation. 13 October 2006. Archived from the original on 19 October 2006. Retrieved 13 October 2006.

- ^ "Listeners name 'greatest Bengali'". BBC News. 14 April 2004. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ "Altamas Kabir to become CJI on Sept 29". Hindustan Times. 4 September 2012. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

Bibliography

- Ahmed, Rafiuddin (1996). The Bengal Muslims, 1871–1906: a quest for identity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-563919-3.

- Ahmed, Rafiuddin (2001). Understanding the Bengal Muslims: interpretative essays. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-565520-9.

- Chakraborty, Ashoke Kumar (2002). Bengali Muslim literati and the development of Muslim community in Bengal. Indian Institute of Advanced Study. ISBN 9788179860120.

- Lahiri, Pradip Kumar (1991). Bengali Muslim thought, 1818–1947: its liberal and rational trends. K.P. Bagchi & Co. ISBN 978-81-7074-067-4.

- Shah, Mohammad (1996). In search of an identity: Bengali Muslims, 1880–1940. K.P. Bagchi & Co. ISBN 978-81-7074-184-8.