Benign tumor

| Benign tumor | |

|---|---|

| Other names | non-cancerous tumor |

intradermal nevus, 10x-cropped | |

| Specialty | Oncology, Pathology |

A benign tumor is a mass of

Some forms of benign tumors may be harmful to health. Benign tumor growth causes a

The word "benign" means "favourable, kind, fortunate, salutary, propitious".[1] However, a benign tumour is not benign in the usual sense; the name merely specifies that it is not "malignant", i.e. cancerous. While benign tumours usually do not pose a serious health risk, they can be harmful or fatal.[2] Many types of benign tumors have the potential to become cancerous (malignant) through a process known as tumor progression. For this reason and other possible harms, some benign tumors are removed by surgery. When removed, benign tumors usually do not return. Exceptions to this rule may indicate malignant transformation.

Signs and symptoms

Benign tumors are very diverse; they may be asymptomatic or may cause specific symptoms, depending on their anatomic location and tissue type. They grow outward, producing large, rounded masses which can cause what is known as a "mass effect". This growth can cause compression of local tissues or organs, leading to many effects, such as blockage of ducts, reduced blood flow (

Causes

PTEN hamartoma syndrome

PTEN hamartoma syndrome encompasses

Familial adenomatous polyposis

Tuberous sclerosis complex

Von Hippel–Lindau disease

Bone tumors

Benign tumors of bone can be similar macroscopically and require a combination of a clinical history with cytogenetic, molecular, and radiologic tests for diagnosis.[23] Three common forms of benign bone tumors with are giant cell tumor of bone, osteochondroma, and enchondroma; other forms of benign bone tumors exist but may be less prevalent.

Giant cell tumors

Giant cell tumors of bone frequently occur in long bone epiphyses of the appendicular skeleton or the sacrum of the axial skeleton. Local growth can cause destruction of neighboring cortical bone and soft tissue, leading to pain and limiting range of motion. The characteristic radiologic finding of giant cell tumors of bone is a lytic lesion that does not have marginal sclerosis of bone. On histology, giant cells of fused osteoclasts are seen as a response to neoplastic mononucleated cells. Notably, giant cells are not unique among benign bone tumors to giant cell tumors of bone. Molecular characteristics of the neoplastic cells causing giant cell tumors of bone indicate an origin of pluripotent mesenchymal stem cells that adopt preosteoblastic markers. Cytogenetic causes of giant cell tumors of bone involve telomeres. Treatment involves surgical curettage with adjuvant bisphosphonates.

Osteochondroma

Osteochondromas form cartilage-capped projections of bone. Structures such as the marrow cavity and cortical bone of the osteochondroma are contiguous to those of the originating bone. Sites of origin often involve metaphyses of long bones. While many osteochondromas occur spontaneously, there are cases in which several osteochondromas can occur in the same individual; these may be linked to a genetic condition known as hereditary multiple osteochondromas. Osteochondroma appears on X-ray as a projecting mass that often points away from joints.[23] These tumors stop growing with the closure of the parental bone's growth plates. Failure to stop growth can be indicative of transformation to malignant chondrosarcoma. Treatment is not indicated unless symptomatic. In that case, surgical excision is often curative.

Enchondroma

Enchondromas are benign tumors of hyaline cartilage. Within a bone, enchondromas are often found in metaphyses. They can be found in many types of bone, including small bones, long bones, and the axial skeleton. X-ray of enchondromas shows well-defined borders and a stippled appearance.[23] Presentation of multiple enchondromas is consistent with multiple enchondromatosis (Ollier Disease). Treatment of enchondromas involves surgical curettage and grafting.

Benign soft tissue tumors

Lipomas

Lipomas are benign, subcutaneous tumors of fat cells (adipocytes). They are usually painless, slow-growing, and mobile masses that can occur anywhere in the body where there are fat cells, but are typically found on the trunk and upper extremities.[24]

[25] Although lipomas can develop at any age, they more commonly appear between the ages of 40 and 60.[24] Lipomas affect about 1% of the population, with no documented sex bias, and about 1 in every 1000 people will have a lipoma within their lifetime.[25][26] The cause of lipomas is not well defined. Genetic or inherited causes of lipomas play a role in around 2-3% of patients.[25] In individuals with inherited familial syndromes such as Proteus syndrome or Familial multiple lipomatosis, it is common to see multiple lipomas across the body.[25] These syndromes are also associated with specific symptoms and sub-populations. Mutations in chromosome 12 have been identified in around 65% of lipoma cases.[25] Lipomas have also been shown to be increased in those with obesity, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus.[25]

Lipomas are usually diagnosed clinically, although imaging (ultrasound, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging) may be utilized to assist with the diagnosis of lipomas in atypical locations.[24] The main treatment for lipomas is surgical excision, after which the tumor is examined with histopathology to confirm the diagnosis.[24] The prognosis for benign lipomas is excellent and recurrence after excision is rare, but may occur if the removal was incomplete.[25]

Mechanism

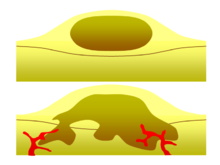

Benign vs malignant

One of the most important factors in classifying a tumor as benign or malignant is its invasive potential. If a tumor lacks the ability to invade adjacent tissues or spread to distant sites by metastasizing then it is benign, whereas invasive or metastatic tumors are malignant.[3] For this reason, benign tumors are not classed as cancer.[27] Benign tumors will grow in a contained area usually encapsulated in a fibrous connective tissue capsule. The growth rates of benign and malignant tumors also differ; benign tumors generally grow more slowly than malignant tumors. Although benign tumors pose a lower health risk than malignant tumors, they both can be life-threatening in certain situations. There are many general characteristics which apply to either benign or malignant tumors, but sometimes one type may show characteristics of the other. For example, benign tumors are mostly well differentiated and malignant tumors are often undifferentiated. However, undifferentiated benign tumors and differentiated malignant tumors can occur.[28][29] Although benign tumors generally grow slowly, cases of fast-growing benign tumors have also been documented.[30] Some malignant tumors are mostly non-metastatic such as in the case of basal-cell carcinoma.[31] CT and chest radiography can be a useful diagnostic exam in visualizing a benign tumor and differentiating it from a malignant tumor. The smaller the tumor on a radiograph the more likely it is to be benign as 80% of lung nodules less than 2 cm in diameter are benign. Most benign nodules are smoothed radiopaque densities with clear margins but these are not exclusive signs of benign tumors.[32]

Multistage carcinogenesis

Tumors are formed by

Diagnosis

Classification

| Cell origin | Cell type | Tumor |

|---|---|---|

Endodermal

|

Biliary tree |

Cholangioma |

Colon |

Colonic polyp | |

Glandular |

Adenoma | |

| Papilloma | ||

| Cystadenoma | ||

| Liver | Liver cell adenoma | |

| Placental | Hydatiform mole

| |

Renal |

Renal tubular adenoma

| |

Squamous |

Squamous cell papilloma | |

| Stomach | Gastric polyp | |

Mesenchymal

|

Blood vessel | Hemangioma, Cardiac myxoma |

| Bone | Osteoma | |

| Cartilage | Chondroma | |

| Fat tissue | Lipoma | |

Fibrous tissue |

Fibroma | |

| Lymphatic vessel | Lymphangioma | |

| Smooth muscle | Leiomyoma | |

Striated muscle |

Rhabdomyoma | |

Ectodermal

|

Glia | Astrocytoma, Schwannoma |

| Melanocytes | Nevus | |

| Meninges | Meningioma | |

Nerve cells |

Ganglioneuroma | |

| Reference[35] | ||

Benign

Exceptions to the nomenclature rules exist for historical reasons; malignant examples include

Benign tumors do not encompass all benign growths. Skin tags, vocal chord polyps, and hyperplastic polyps of the colon are often referred to as benign, but they are overgrowths of normal tissue rather than neoplasms.[36]

Treatment

Benign tumors typically need no treatment unless if they cause problems such as seizures, discomfort or cosmetic concerns.

References

- ^ "Benign". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Rao AK (February 2021). "Overview of Heart Tumors - Treatment of noncancerous (benign) heart tumors". MSD Manual Consumer Version.

Children with this type of [inoperable, benign] tumor usually die of an abnormal heart rhythm at an early age.

- ^ ISBN 0-443-10101-9.

- S2CID 19272145.

- PMID 16253900.

- ISBN 92-832-2416-7.

- PMID 11588539.

- S2CID 20915929.

- ^ Zuber M, Harder F (2001). Benign tumors of the colon and rectum. Munich: Zuckschwerdt: Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented.

- PMID 31216739.

- ^ PMID 19668082.

- PMID 15121767.

- PMID 11073535.

- S2CID 13417857.

- PMID 18781191.

- S2CID 31873101.

- S2CID 8516051.

- S2CID 8743.

- ^ S2CID 205344131.

- S2CID 3579356.

- S2CID 41992893.

- PMID 15579030.

- ^ PMID 21675379.

- ^ PMID 30244263.

- ^ PMID 29939683, retrieved 2022-09-19

- PMID 29493968, retrieved 2022-09-19

- ISBN 0-7613-2833-5.

- PMID 10366409.

- PMID 23106056.

- PMID 5681331.

- ISBN 978-1605479682.

- PMID 10682770.

- PMID 1911211.

- PMID 8354184.

- ISBN 978-0-7637-6357-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-9516-6.

- ISBN 0-7216-7335-X.

- ^ a b Zuber M, Harder F (2001). Benign tumors of the colon and rectum. Munich: Zuckschwerdt: Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented.

- PMID 23462704.

- S2CID 28106960.

- PMID 12613727.

- PMID 18395671.