Benzodiazepine use disorder

| Benzodiazepine use disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Benzodiazepine drug misuse |

Addiction Medicine, Psychiatry | |

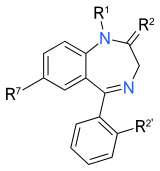

| Benzodiazepines |

|---|

|

Benzodiazepine use disorder (BUD), also called misuse or abuse,

In tests in pentobarbital-trained rhesus monkeys benzodiazepines produced effects similar to barbiturates.[5] In a 1991 study, triazolam had the highest self-administration rate in cocaine trained baboons, among the five benzodiazepines examined: alprazolam, bromazepam, chlordiazepoxide, lorazepam, triazolam.[6] A 1985 study found that triazolam and temazepam maintained higher rates of self-injection in both human and animal subjects compared to a variety of other benzodiazepines (others examined: diazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, flurazepam, alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, nitrazepam, flunitrazepam, bromazepam, and clorazepate).[7] A 1991 study indicated that diazepam, in particular, had a greater abuse liability among people who were drug abusers than did many of the other benzodiazepines. Some of the available data also suggested that lorazepam and alprazolam are more diazepam-like in having relatively high abuse liability, while oxazepam, halazepam, and possibly chlordiazepoxide, are relatively low in this regard.[8] A 1991–1993 British study found that the hypnotics flurazepam and temazepam were more toxic than average benzodiazepines in overdose.[9] A 1995 study found that temazepam is more rapidly absorbed and oxazepam is more slowly absorbed than most other benzodiazepines.[10] Benzodiazepines have been abused both orally and intravenously. Different benzodiazepines have different abuse potential; the more rapid the increase in the plasma level following ingestion, the greater the intoxicating effect and the more open to abuse the drug becomes. The speed of onset of action of a particular benzodiazepine correlates well with the 'popularity' of that drug for abuse. The two most common reasons for preference were that a benzodiazepine was 'strong' and that it gave a good 'high'.[11]

According to Dr. Chris Ford, former clinical director of Substance Misuse Management in General Practice, among

Signs and symptoms

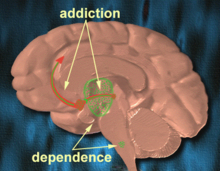

Sedative-hypnotics such as alcohol, benzodiazepines, and the barbiturates are known for the severe physical dependence that they are capable of inducing which can result in severe withdrawal effects.[13] This severe neuroadaptation is even more profound in high dose drug users and misusers. A high degree of tolerance often occurs in chronic benzodiazepine abusers due to the typically high doses they consume which can lead to a severe benzodiazepine dependence. The benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome seen in chronic high dose benzodiazepine abusers is similar to that seen in therapeutic low dose users but of a more severe nature. Extreme antisocial behaviors in obtaining continued supplies and severe drug-seeking behavior when withdrawals occur. The severity of the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome has been described by one benzodiazepine drug misuser who stated that:[14]

I'd rather withdraw off heroin any day. If I was withdrawing from benzos you could offer me a gram of heroin or just 20mg of diazepam and I'd take the diazepam every time – I've never been so frightened in my life.

Those who use benzodiazepines intermittently are less likely to develop a dependence and withdrawal symptoms upon dose reduction or cessation of benzodiazepines than those who use benzodiazepines on a daily basis.[14]

Misuse of benzodiazepines is widespread amongst drug misusers; however, many of these people will not require withdrawal management as their use is often restricted to binges or occasional misuse. Benzodiazepine dependence when it occurs requires withdrawal treatment. There is little evidence of benefit from long-term substitution therapy of benzodiazepines, and conversely, there is growing evidence of the harm of

Tolerance leads to a reduction in GABA receptors and function; when benzodiazepines are reduced or stopped this leads to an unmasking of these compensatory changes in the nervous system with the appearance of physical and mental withdrawal effects such as anxiety, insomnia, autonomic hyperactivity and possibly seizures.[18]

Common withdrawal symptoms

Include the following:[14]

- Depression

- Shaking

- Feeling unreal

- Appetite loss

- Muscle twitching

- Severe and debilitating insomnia

- Memory loss

- Motor impairment

- Nausea

- Muscle pains

- Dizziness

- Apparent movement of still objects

- Feeling faint

- Noise sensitivity

- Light sensitivity

- Peculiar taste

- Pins and needles

- Touch sensitivity

- Sore eyes

- Hallucinations

- Smell sensitivity

All sedative-hypnotics, e.g. alcohol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines and

Background

Benzodiazepines are a commonly abused class of drugs, although there is debate as to whether certain benzodiazepines have higher abuse potential than others.[19] In animal and human studies the abuse potential of benzodiazepines is classed as moderate in comparison to other drugs of abuse.[20] Benzodiazepines are commonly abused by

Benzodiazepine abuse increases risk-taking behaviors such as unprotected sex and sharing of needles amongst intravenous abusers of benzodiazepines. Abuse is also associated with blackouts, memory loss, aggression, violence, and chaotic behavior associated with paranoia. There is little support for long-term maintenance of benzodiazepine abusers and thus a withdrawal regime is indicated when benzodiazepine abuse becomes a dependence. The main source of illicit benzodiazepines are diverted benzodiazepines obtained originally on prescription; other sources include thefts from pharmacies and pharmaceutical warehouses. Benzodiazepine abuse is steadily increasing and is now a major public health problem. Benzodiazepine abuse is mostly limited to individuals who abuse other drugs, i.e. poly-drug abusers. Most prescribed users do not abuse their medication, however, some high dose prescribed users do become involved with the illicit drug scene. Abuse of benzodiazepines occurs in a wide age range of people and includes teenagers and the old. The abuse potential or drug-liking effects appears to be dose related, with low doses of benzodiazepines having limited drug liking effects but higher doses increasing the abuse potential/drug-liking properties.[22]

Complications of benzodiazepine abuse include drug-related deaths due to overdose especially in combination with other depressant drugs such as

Use is widespread among amphetamine users, with those that use amphetamines and benzodiazepines having greater levels of mental health problems and social deterioration. Benzodiazepine injectors are almost four times more likely to inject using a shared needle than non-benzodiazepine-using injectors. It has been concluded in various studies that benzodiazepine use causes greater levels of risk and psycho-social dysfunction among drug misusers.[24] Poly-drug users who also use benzodiazepines appear to engage in more frequent high-risk behaviors. Polydrug use involving benzodiazepines and alcohol can result in blackouts, increased risk-taking behaviour, and in severe cases seizures and overdose.[25] Those who use stimulant and depressant drugs are more likely to report adverse reactions from stimulant use, more likely to be injecting stimulants and more likely to have been treated for a drug problem than those using stimulant but not depressant drugs.[26]

Risk factors

Individuals with a substance abuse history are at an increased risk of misusing benzodiazepines.[27]

Several (primary research) studies, even into the last decade, claimed that individuals with a history of familial abuse of alcohol or who are siblings or children of alcoholics appeared to respond differently to benzodiazepines than so called genetically healthy persons, with males experiencing increased euphoric effects and females having exaggerated responses to the adverse effects of benzodiazepines.[28][29][30][31]

Whilst all benzodiazepines have abuse potential, certain characteristics increase the potential of particular benzodiazepines for abuse. Worldwide, diazepam is the benzodiazepine most frequently encountered by customs and law enforcement. Diazepam is available for very cheap in every country. These characteristics are chiefly practical ones—most especially, availability (often based on popular perception of 'dangerous' versus 'none dangerous' drugs) through prescribing physicians or illicit distributors. Pharmacological and pharmacokinetic factors are also crucial in determining abuse potentials. A short

| Drug Name | Common Brand Names* | Onset of action | Duration of action (h)** | Elimination Half-Life (h ) [active metabolite] |

Approximate Equivalent Dose (PO)*** |

| Alprazolam | Xanax, Xanor, Tafil, Alprox, Niravam, Ksalol, Solanax | Intermediate | 3–5 | 11-13 [10–20 hours] | 0.5 mg |

| Chlordiazepoxide | Librium, Tropium, Risolid, Klopoxid | Intermediate | 4-6 | 5–30 hours [36–200 hours] | 25 mg |

| Clonazepam | Klonopin, Klonapin, Rivotril, Iktorivil | Intermediate | 10–12 | 18–50 hours | 0.5 mg |

| Clorazepate | Tranxene | Intermediate | 6-8 | [36–100 hours] | 15 mg |

| Diazepam | Valium, Apzepam, Stesolid, Vival, Apozepam, Hexalid, Valaxona | Fast | 1–6 | 20–100 hours [36–200] | 10 mg |

| Etizolam**** | Etivan | Fast | 5-7 | 6-8 h | 1 mg |

| Estazolam | ProSom | Slow | 2–6 | 10–24 h | 2 mg |

| Flunitrazepam | Rohypnol, Fluscand, Flunipam, Ronal | Fast | 6–8 | 18–26 hours [36–200 hours] | 1 mg |

| Flurazepam | Dalmadorm, Dalmane | Fast | 7–10 | 20 mg | |

| Lorazepam | Ativan, Temesta, Lorabenz, Tavor | Intermediate | 2–6 | 10–20 hours | 1 mg |

| Midazolam | Dormicum, Versed, Hypnovel, Flormidal | Fast | 0.5–1 | 3 hours (1.8–6 hours) | 10 mg |

| Nitrazepam | Mogadon, Nitrosun, Epam, Alodorm, Insomin | Fast | 4-8 | 16–38 hours | 10 mg |

| Oxazepam | Seresta, Serax, Serenid, Serepax, Sobril, Oxascand, Alopam, Oxabenz, Oxapax | Slow | 4–6 | 4–15 hours | 30 mg |

| Prazepam | Lysanxia, Centrax | Intermediate | 6-9 | 36–200 hours | 20 mg |

| Quazepam | Doral | Slow | 6 | 39–120 hours | 20 mg |

| Temazepam | Restoril, Normison, Euhypnos, Tenox | Fast | 1-4 | 4–11 hours | 20 mg |

| Triazolam | Halcion, Rilamir | Fast | 0.5–1 | 2 hours | 0.25 mg |

*Not all trade names are listed. Click on the drug name to see a more comprehensive list.

**The duration of apparent action is usually considerably less than the half-life. With most benzodiazepines, noticeable effects usually wear off within a few hours. Nevertheless, as long as the drug is present it will exert subtle effects within the body. These effects may become apparent during continued use or may appear as withdrawal symptoms when dosage is reduced or the drug is stopped.[citation needed]

***Equivalent doses are based on clinical experience but may vary between individuals.[34]

****Etizolam is not a true benzodiazepine but has similar chemistry, effects, and abuse potential.

Epidemiology

Little attention has focused on the degree that benzodiazepines are abused as a primary drug of choice, but they are frequently abused alongside other drugs of abuse, especially alcohol, stimulants and opiates.[16] The benzodiazepine most commonly abused can vary from country to country and depends on factors including local popularity as well as which benzodiazepines are available. Nitrazepam for example is commonly abused in Nepal and the United Kingdom,[35][36] whereas in the United States of America where nitrazepam is not available on prescription other benzodiazepines are more commonly abused.[8] In the United Kingdom and Australia there have been epidemics of temazepam abuse. Particular problems with abuse of temazepam are often related to gel capsules being melted and injected and drug-related deaths.[37][38][39] Injecting most benzodiazepines is dangerous because of their relative insolubility in water (with the exception of midazolam), leading to potentially serious adverse health consequences for users.[40][41]

Benzodiazepines are a commonly misused class of drug. A study in Sweden found that benzodiazepines are the most common drug class of forged prescriptions in Sweden.[42] Concentrations of benzodiazepines detected in impaired motor vehicle drivers often exceeding therapeutic doses have been reported in Sweden and in Northern Ireland.[43][44] One of the hallmarks of problematic benzodiazepine drug misuse is escalation of dose. Most licit prescribed users of benzodiazepines do not escalate their dose of benzodiazepines.[45]

Society and culture

Problem benzodiazepine use can be associated with various

Benzodiazepines are also sometimes used for drug facilitated sexual assaults and robbery, however, alcohol remains the most common drug involved in drug facilitated assaults. The muscle relaxant, disinhibiting and amnesia producing effects of benzodiazepines are the pharmacological properties which make these drugs effective in drug-facilitated crimes.[47][48] Serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer admitted to using triazolam (Halcion), and occasionally temazepam (Restoril), in order to sedate his victims prior to murdering them.[49]

In a 2017 publication, an analysis of the blood samples of 22 victims of drug-facilitated robberies in Bangladesh revealed that criminals use different mixtures of Benzodiazepines including Lorazepam, Midazolam, Diazepam and Nordiazepam to immobilize and then rob their victims.[50]

Drug regulation and enforcement

Europe

Oceania

Benzodiazepines are common drugs of abuse in Australia and New Zealand, particularly among those who may also be using other illicit drugs. The intravenous use of temazepam poses the greatest threat to those who misuse benzodiazepines. Simultaneous consumption of temazepam with heroin is a potential risk factor of overdose. An Australian study of non-fatal heroin overdoses noted that 26% of heroin users had consumed temazepam at the time of their overdose. This is consistent with an NSW investigation of coronial files from 1992. Temazepam was found in 26% of heroin-related deaths. Temazepam, including tablet formulations, are used intravenously. In an Australian study of 210 heroin users who used temazepam, 48% had injected it. Although abuse of benzodiazepines has decreased over the past few years, temazepam continues to be a major drug of abuse in Australia. In certain states like Victoria and Queensland, temazepam accounts for most benzodiazepine sought by forgery of prescriptions and through pharmacy burglary. Darke, Ross & Hall found that different benzodiazepines have different abuse potential. The more rapid the increase in the plasma level following ingestion, the greater the intoxicating effect and the more open to abuse the drug becomes. The speed of onset of action of a particular benzodiazepine correlates well with the 'popularity' of that drug for abuse. The two most common reasons for preference for a benzodiazepine were that it was the 'strongest' and that it gave a good 'high'.[11]

North America

The most frequently abused of the benzodiazepines in both the United States and Canada are alprazolam, clonazepam, lorazepam and diazepam.[54] In Canada, bromazepam is marketed and is a highly effective anxiolytic, muscle-relaxant, and sedative. Bromazepam has shown itself to be at least as effective as alprazolam as anxiolytic, and a superior sedative.

East and Southeast Asia

The Central Narcotics Bureau of Singapore seized 94,200 nimetazepam tablets in 2003. This is the largest nimetazepam seizure recorded since nimetazepam became a controlled drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act in 1992. In Singapore nimetazepam is a Class C controlled drug.[55]

In Hong Kong abuse of prescription medicinal preparations continued in 2006 and seizures of midazolam (120,611 tablets), nimetazepam/nitrazepam (17,457 tablets), triazolam (1,071 tablets), diazepam (48,923 tablets) and chlordiazepoxide (5,853 tablets) were made. Heroin addicts used such tablets (crushed and mixed with heroin) to prolong the effect of the narcotic and ease withdrawal symptoms.[56]

See also

- Drug abuse

- Benzodiazepine overdose

- Effects of long-term benzodiazepine use

- Drug facilitated sexual assault

References

- ^ "Benzodiazepine dependence: reduce the risk". NPS MedicineWise. Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-521-84228-0.

- ^ PMID 16336040. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- PMID 1684083.

- S2CID 24836734.

- S2CID 30449419.

- S2CID 17366074. Archived from the original(PDF) on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ S2CID 28209526.

- S2CID 46001278.

- PMID 7866122.

- ^ a b Australian Government; Medical Board (2006). "ACT MEDICAL BOARD – STANDARDS STATEMENT – PRESCRIBING OF BENZODIAZEPINES" (PDF). Australia: ACT medical board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ^ Chris Ford (2009). "What is possible with benzodiazepines". UK: Exchange Supplies, 2009 National Drug Treatment Conference. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010.

- ^ Ray Baker. "Dr Ray Baker's Article on Addiction: Benzodiazepines in Particular". Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Ashton, C. H. (2002). "BENZODIAZEPINE ABUSE". Drugs and Dependence. Harwood Academic Publishers. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- ^ National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse (2007). "Drug misuse and dependence – UK guidelines on clinical management" (PDF). United Kingdom: Department of Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8493-1690-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7817-6998-3.

- ^ PMID 10779253. Archived from the originalon 12 May 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- S2CID 23960995. Archived from the originalon 12 January 2002. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- S2CID 40680580.

- ISBN 978-0-415-27891-1.

- ISBN 978-1-58562-276-4.

- PMID 7866252.

- .

- PMID 9088780.

- Hoffmann–La Roche. "Mogadon". RxMed. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- PMID 3417618.

- PMID 8659624.

- S2CID 10076182.

- S2CID 26676149.

- ISBN 978-1-58562-276-4.

- PMID 6133535.

- ^ "benzo.org.uk : Benzodiazepine Equivalence Table". benzo.org.uk.

- PMID 9839033.

- S2CID 42665843.

- .

- ^ Ashton, H. (2002). "Benzodiazepine Abuse". Drugs and Dependence. London & New York: Harwood Academic Publishers.

- PMID 7663317.

- PMID 27298694. Archived from the originalon 23 June 2008.

- ^ "DB00404 (Alprazolam)". Canada: DrugBank. 26 August 2008.

- S2CID 19770310.

- S2CID 25511804.

- PMID 3804143.

- S2CID 43443180.

- ISBN 978-1-921185-39-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2009.)

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help - PMID 10881768.

- S2CID 28052263.

- ISBN 978-0-415-87624-7.

- ISSN 2322-2611.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ The Scottish Government (3 June 2008). "Statistical Bulletin – Drug Seizures by Scottish Police Forces, 2005/2006 and 2006/2007" (PDF). Crime and Justice Series. Scotland: scotland.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- INCB (January 1999). "Operation of the international drug control system" (PDF). incb.org. Archived from the original(PDF) on 17 November 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ Northern Ireland Government (October 2008). "Statistics from the Northern Ireland Drug Misuse Database: 1 April 2007 – 31 March 2008" (PDF). Northern Ireland: Department of Health and Social Services and Public Safety.

- United States Government; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2006). "Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2006: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Archived from the originalon 18 January 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ Central Narcotics Bureau; Singapore Government (2003). "Drug Situation Report 2003". Singapore: cnb.gov.sg. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Hong Kong Government. "Suppression of Illicit Trafficking and Manufacturing"(PDF). Hong Kong: nd.gov.hk. Retrieved 13 February 2009.