Bible translations in the Middle Ages

Terminology

- Vernacular: the native language of a community, such as Middle English; tending to be non-literate, evolving, borrowing and part of a dialect continuum, perhaps without a sophisticated vocabulary for abstract ideas.

- trade languages, such as koine Greek, but prone to being superseded as economic patterns change. When a text is available in the lingua franca there may be little demand for or benefit from a vernacular translation.

- Official language: the language used in or by officialdom, such as Roman era Latin; tending to change slowly over time and with a large abstract vocabulary. When a text is available in the official language, there may be little patronage available to fund the translation and expensive production of a vernacular translation.

- Sacred language: a language used for sacred purposes, not in common use, and tending to be quite stable over centuries or millennia.

In the modern core Anglosphere nations, English is typically the vernacular, the official language, and a lingua franca, though (especially for Protestants) there is no sacred language. Sacred languages may start as vernaculars, then go through various levels of solidification. Biblical translations into vernacular languages often rely on previous translations in the same language or language group.

Classical and Late Antiquity translations

By the end of late antiquity the Bible was available and used in all the major written languages then spoken by Christians.

Greek texts and versions

The books of the Bible were not originally written in

The whole Christian Bible, including the

Other early versions

The Bible was translated into various languages in

At the end of this period (c700s),

Vetus Latina, or the Old Latin

The earliest Latin translations are collectively known as the Vetus Latina. These Old Latin translations date from at least the early fourth century, and exhibit a great number of minor variations. Usage of the Vetus Latina as the backbone of the church and liturgy continued well into the Twelfth Century. Perhaps the most complete, and certainly the largest surviving example is Codex Gigas, which can be seen in its entirety online.[5] Housed in the National Library of Sweden, the massive Bible opens with the Five Books of Moses and ends with Third Book of Kings.

Latin Vulgate

In the late fourth century, Jerome re-translated the Hebrew and Greek texts into the normal vernacular Latin of his day, in a version known as the Vulgate (Biblia vulgata) (meaning "common version", in the sense of "popular").

The Old Testament books are Jerome's translation from the Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek. The New Testament books are rescensions of Vetus Latina versions: the Gospels by Jerome with reference to some Greek and Aramaic versions, and the other parts perhaps by a Rufinas.

When Jerome's revision was read aloud in the churches in North Africa, riots and protests erupted since the new readings differed in phraseology from the more familiar reading in the Vetus Latina.

Jerome's translation gradually replaced most of the older Latin texts, and also gradually ceased to be a vernacular version as the Latin language developed and divided. The earliest surviving complete manuscript of the entire Latin Bible is the

Psalms

The Psalms had multiple translations in Latin made for chanting, and for different

It also has been common to create metrical semi-paraphrases of Psalms, to suit songs and metrical recitation, in cultures where this was prized, such as Middle English,[6] and in Protestant hymnody where the words could be sung over any popular tune of the same metre. Restrictions on unauthorized new Bible translations do not see to have applied to the Psalms.

As well as translations that attempt more satisfactory lyrical use, there are translations that do not attempt any poetic facade, such as Richard Rolle's Middle English Prose Psalter (c. 1348) [7]

In English, the Psalms in the Book of Common Prayer come from the Coverdale Bible not the King James Version Bible.

Early medieval vernacular translations

During the

Meanwhile, Latin was evolving into new distinct regional forms, the early versions of the Romance languages, for which new translations eventually became necessary. However, the Vulgate remained the authoritative text, used universally in the West for scholarship and the liturgy, matching its continued use for other purposes such as religious literature and most secular books and documents.

In the early Middle Ages, anyone who could read at all could often read Latin, even in

The history of ad hoc translations of scripture readings at Mass has not been well studied. In the early Middle Ages, as the Romance languages progressively diverged from Latin, lectors would read the Latin using the conventions of the local dialect. The acts of Saint Gall contain a reference to the use of a vernacular interpreter in Mass as early as the seventh century, and the 813 Council of Tours acknowledged the need for translation and encouraged such.[11] The prône portion of Pre-Tridentine Latin Mass would include such translations by the priest as needed during the vernacular homily.

Factors promoting and inhibiting vernacular translations

Translations came relatively late in the history of many of the European vernacular languages. They were rare in peripheral areas and with languages in flux that did not have vocabularies suitable to translate biblical terms, things and phrases. According to the Cambridge History of the Bible, this was mainly because "the vernacular appeared simply and totally inadequate. Its use, it would seem, could end only in a complete enfeeblement of meaning and a general abasement of values. Not until a vernacular is seen to possess relevance and resources, and, above all, has acquired a significant cultural prestige, can we look for acceptable and successful translation."[12][13]

The cost of commissioning translations and producing such a large work in manuscript was also a factor; the three copies of the Vulgate produced in 7th century

In the 12th and 13th centuries, particular demand for vernacular translations came from groups outside the Roman Catholic Church such as the Waldensians, and Cathars. This was probably related to the increased urbanization of the 12th century, as well as increased literacy among educated urban populations.[15][16]

Innocent III

Church attitudes toward written translations varied by the translation, the date and location, but is controversial,

A well-known group of letters from

Margaret Deanesly's study of this matter in 1920 was influential in maintaining this notion for many years, but later scholars have challenged its conclusions.

While the documents are inconclusive about the fate of the specific translations in question and their users, Innocent’s general remarks suggest a rather permissive attitude toward translations and vernacular commentaries provided that they are produced and used within the scope of Christian teachings or with church oversight.

Regional bans

There is no evidence of any official decision in the Medieval era to universally disallow translations following the incident at Metz. In 1417, influential Paris theologian Jean Gerson asked the Council of Constance to ban public unauthorized reading of vernacular scriptures across the entire Church, but gained no traction at the Council.[21]: 34

However, some specific translations were condemned, and bans were imposed in some regions following assassinations or revolts.

- During the Cathars in mind as well as the Waldensians, who continued to preach using their own translations, spreading into Spain and Italy, as well as the Holy Roman Empire.

- In England in the 1400s, production of new translations of the Bible, public reading of unauthorised versions, and any texts containing Oxford Constitutions.

As Rosemarie Potz McGerr has argued, as a general pattern, bans on translation responded to the threat of strong heretical movements; in the absence of viable heresies, a variety of translations and vernacular adaptations flourished between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries with no documented institutional opposition at all.[24]

By the Council of Trent the Reformation challenged the Catholic Church, and the "rediscovery" of the Greek New Testament presented new opportunities for divergent renditions by translators, so the issue of unauthorised vernacular Bible reading came to the foreground, with cardinals from Romance-language backgrounds (i.e. France, Spain, Italy) generally believing that the vernacular was not important, while cardinals from non-Romance-language regions supporting vernacular study (the "beer-wine" split).[25]

Notable medieval vernacular Bibles by language, region and type

English

There are a number of partial

After the Norman Conquest, the Ormulum, produced by the Augustinian friar Orm of Lincolnshire around 1150, includes partial translations of the Gospels and Acts of the Apostles from Latin into the dialect of East Midland. The manuscript is written in the poetic meter iambic septenarius.

Richard Rolle of Hampole (or de Hampole) was an Oxford-educated hermit and writer of religious texts. In the early 14th century, he produced English glosses of Latin Bible text, including the Psalms. Rolle translated the Psalms into a Northern English dialect, but later copies were written in Southern English dialects. Around the same time, an anonymous author in the West Midlands region produced another gloss of the Psalms — the West Midland Psalms.

In the early years of the 14th century, a French copy of the Book of Revelation was anonymously translated into English, and there were English versions of various French paraphrases and moralized versions.

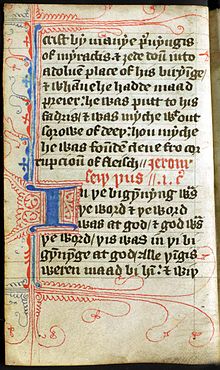

In the late 14th century, probably John Wycliffe and perhaps Nicholas Hereford produced the first complete Middle English language Bible. The Wycliffean Bibles were made in the last years of the 14th century, with two very different translations, the Early Version and the Late Version, the second more numerous than the first, both circulating widely. Other translations or revisions may have been lost: for example the Paues New Testament translation was discovered in around 1904.

Western Continental Europe

The first

French

Prior to the thirteenth century, the Narbonne school of glossators was an influential center of European Biblical translation, particularly for Jewish scholarship according to some scholars.[28] Translations of individual

Completed with prologues in 1297 by

(Castilian) Spanish

The

German

An Old High German version of the Gospel of Matthew dates from 748. In the late Middle Ages, Deanesly thought that Bible translations were easier to produce in Germany, where the decentralized nature of the Empire allowed for greater religious freedom.[36]

Altogether there were 13 known medieval German translations before the Luther Bible,[37] including in the Saxon and Lower Rhenish dialects.

In 1466, Johannes Mentelin published the first printed vernacular Bible, the Mentelin Bible in Middle High German. The Mentelin Bible was reprinted in the southern German region a further thirteen times by various printers until the Luther Bible. About 1475, Günther Zainer of Augsburg printed an illustrated German edition of the Bible, with a second edition in 1477. According to historian Wim François, "about seventy German vernacular Bible texts were printed between 1466 and 1522," eighteen of them being full Bibles.[21]: 37

Czech

All medieval translations of the Bible into Czech were based on the Latin Vulgate. The Psalms were translated into Czech before 1300 and the gospels followed in the first half of the 14th century. The first translation of the whole Bible into Czech was done around 1360. Until the end of the 15th century this translation was revisioned and edited three times. After 1476 the first printed Czech New Testament was published in Pilsen. In 1488 the Prague Bible was published as the oldest Czech printed Bible, thus the Czech language became the fifth language in which the entire Bible was printed (after Latin, German, Italian and Catalan).

Eastern Europe

Some fragments of the Bible were probably translated into Lithuanian when that country was converted to Christianity in the 14th century. A Hungarian Hussite Bible appeared in the mid 15th century, of which only fragments remain.[38]

László Báthory translated the Bible into Hungarian circa 1456,[39] but no contemporary copies have survived. However, the 16th century Jordánszky Codex is most likely a copy of Báthory's work in the 15th century.[40]

Other Germanic and Slavonic languages

The earliest translation into a vernacular European language other than Latin or Greek was the

The translation into

Arabic

In the 10th century, Saadia Gaon translated the Old Testament in Arabic. Ishaq ibn Balask of Cordoba translated the gospels into Arabic in 946.[41] Hafs ibn Albar made a translation of the Psalms in 889.[42]

Poetic and pictorial works

Throughout the Middle Ages, Bible stories were always known in the vernacular through prose and poetic adaptations, usually greatly shortened and freely reworked, especially to include

Historical works

Historians also used the Bible as a source and some of their works were later translated into a vernacular language: for example

Notes

- ^ Walther & Wolf, pp. 242-47

- ^ Parts of the Book of Daniel and Book of Ezra

- ^ "Bible v. Sogdian Translations". Encyclopaedia Iranica online.

- ISBN 978-90-272-8418-1.

- ^ "Devil's Bible". 1200.

- ^ "Psalter, English metrical version ('Surtees Psalter') [Middle English] - Medieval Manuscripts". medieval.bodleian.ox.ac.uk.

- ISSN 0026-7937.

- ^ For instance, see Roberts, Jane (2011). “Some Psalter Glosses in Their Immediate Context”, in Palimpsests and the Literary Imagination of Medieval England, eds. Leo Carruthers, Raeleen Chai-Elsholz, Tatjana Silec. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 61-79, which looks at three Anglo-Saxon glossed psalters and how layers of gloss and text, language and layout, speak to the meditative reader, or Marsden, Richard (2011), "The Bible in English in the Middle Ages", in The Practice of the Bible in the Middle Ages: Production, Reception and Performance in Western Christianity (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), pp. 272-295.

- ^ Deanesly, Margaret (1920) The Lollard Bible and Other Medieval Biblical Versions. Cambridge University Press, p. 19

- ^ Lampe (1975)

- ^ Gustave Masson (1866), pp. 81-83.

- ^ Lampe, G. W. H. (ed.) (1975) The Cambridge History of the Bible, vol. 2: The West from the Fathers to the Reformation, p. 366.

- early modern English, pointing out numerous neologisms.

- ISBN 0-7190-5053-7

- ^ Kienzle, Beverly Mayne (1998) "Holiness and obedience"; pp. 259-60.

- ^ Biller (1994)

- ^ Deanesly (1920), p. 34.

- ^ Boyle, Leonard E. (1985) "Innocent III and vernacular versions of Scripture"; p. 101.

- ^ Boyle, pg. 105

- ^ Boyle (1985), p. 105.

- ^ .

- ^ McGerr (1983), p. 215

- ^ Anderson, Trevor (5 June 2017). "Vernacular Scripture in the Reformation Era: Re-examining the Narrative". The Regensburg Forum. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ McGerr (1983)

- ^ Thomson, Ian (26 February 2017). "Reformation Divided: Catholics, Protestants and the Conversion of England by Eamon Duffy – review". The Observer.

- ^ Lindisfarne Gospels British Library

- ^ Thompson (2004), p. 4

- ^ Alfonso, Esperanza, editor, del Barco, Javier. et al. Translating the Hebrew Bible in Medieval Iberia: Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Hunt. 268. Netherlands, Brill, 2021. p. 5ff, p. 193, & p. 199. Google Preview ISBN 9789004461222.

- ^ Nobel (2002)

- ^ Berger (1884)

- ^ Sneddon (2002)

- ^ C. A. Robson, “Vernacular Scriputres in France” in Lampe, ‘’Cambridge History of the Bible’’ (1975)

- ^ Berger (1884), pp. 109-220

- ^ Serrano, Rafael (29 de enero de 2014). «La Biblia alfonsina». Historia de la Biblia en español. Accessed 22 June 2020.

- ISBN 8482675192, pg. 479.

- ^ Deanesly (1920), pp. 54-61.

- ^ Walther & Wolf, p. 242

- ^ "The Oldest Book of Gospels in Hungarian". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ "Magyar szentek és boldogok". katolikus.hu (in Hungarian). Archived from the original on 2008-12-16.

- ^ László Mezey (1956). "A "Báthory-biblia" körül. A mű és szerző" [Around the "Báthory Bible". The work and author]. A Magyar Tudományos Akadémia Nyelv- és Irodalomtudományi Osztályának Közleményei (in Hungarian).

191-221.1

- ^ Ann Christys, Christians in Al-Andalus, 2002, p. 155

- ^ Ann Christys, Christians in Al-Andalus, 2002, p. 155

- ^ Wilson & Wilson, especially pp. 26-30, 120

Sources

- Berger, Samuel. (1884) ‘’La Bible française au moyen âge: étude sur les plus anciennes versions de la Bible écrites en prose de langue d'oï’’l. Paris: Imprimerie nationale.

- Biller, Peter and Anne, eds. (1994). Hudson. Heresy and Literacy, 1000-1530. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Boyle, Leonard E. (1985) "Innocent III and Vernacular Versions of Scripture", in The Bible in the Medieval World: essays in memory of Beryl Smalley, ed. Katherine Walsh and Diana Wood, (Studies in Church History; Subsidia; 4.) Oxford: Published for the Ecclesiastical History Society by Blackwell

- Deanesly, Margaret (1920) The Lollard Bible and Other Medieval Biblical Versions. Cambridge: University Press

- Kienzle, Beverly Mayne (1998) "Holiness and Obedience: denouncement of twelfth-century Waldensian lay preaching", in The Devil, Heresy, and Witchcraft in the Middle Ages: Essays in Honor of Jeffrey B. Russell, ed. Alberto Ferreiro. Leiden: Brill

- Lampe, G. W. H. (1975) The Cambridge History of the Bible, vol. 2: The West from the Fathers to the Reformation. Cambridge: University Press

- Masson, Gustave (1866). “Biblical Literature in France during the Middle Ages: Peter Comestor and Guiart Desmoulins.” ‘’The Journal of Sacred Literature and Biblical Record’’ 8: 81-106.

- McGerr, Rosemarie Potz (1983). “Guyart Desmoulins, the Vernacular Master of Histories, and His ‘’Bible Historiale’’.” ‘’Viator’’ 14: 211-244.

- Nobel, Pierre (2001). “Early Biblical Translators and their Readers: the Example of the ‘’Bible d'Acre and the Bible Anglo-Normande’’.” ‘’Revue de linguistique romane ‘’66, no. 263-4 (2002): 451-472.

- Salvador, Xavier-Laurent (2007). ‘’Vérité et Écriture(s).’’ Bibliothèque de grammaire et de linguistique 25. Paris: H. Champion.

- Sneddon, Clive R. (2002). “The 'Bible Du XIIIe Siècle': Its Medieval Public in Light of its Manuscript Tradition.” ‘’Nottingham Medieval Studies’’ 46: 25-44.

- Thompson, Victoria (2004). Dying and Death in Later Anglo-Saxon England. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-070-1.

- Walther, Ingo F. and Wolf, Norbert (2005) Masterpieces of Illumination (Codices Illustres), Köln: Taschen ISBN 3-8228-4750-X

- Wilson, Adrian, and Wilson, Joyce Lancaster (1984) A Medieval Mirror: "Speculum humanae salvationis", 1324-1500 . Berkeley: University of California Press online edition Includes a full set of woodcut pictures with notes from the Speculum Humanae Salvationis in Chapter 6.