Biogeochemical cycle

| Part of a series on |

| Biogeochemical cycles |

|---|

|

A biogeochemical cycle, or more generally a cycle of matter,

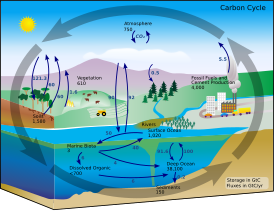

For example, in the carbon cycle, atmospheric

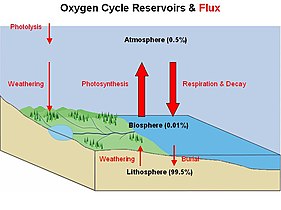

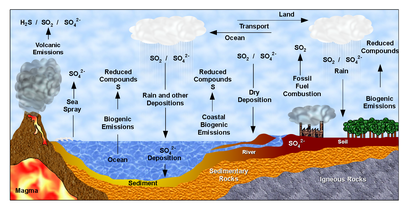

There are biogeochemical cycles for many other elements, such as for oxygen, hydrogen, phosphorus, calcium, iron, sulfur, mercury and selenium. There are also cycles for molecules, such as water and silica. In addition there are macroscopic cycles such as the rock cycle, and human-induced cycles for synthetic compounds such as for polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). In some cycles there are geological reservoirs where substances can remain or be sequestered for long periods of time.

Biogeochemical cycles involve the interaction of biological, geological, and chemical processes. Biological processes include the influence of

Overview

Energy flows directionally through ecosystems, entering as sunlight (or inorganic molecules for

The six aforementioned elements are used by organisms in a variety of ways. Hydrogen and oxygen are found in water and

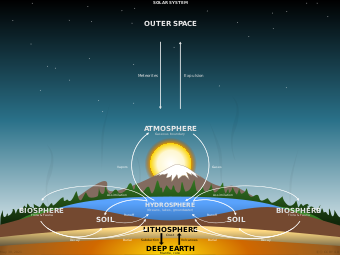

Ecological systems (ecosystems) have many biogeochemical cycles operating as a part of the system, for example, the water cycle, the carbon cycle, the nitrogen cycle, etc. All chemical elements occurring in organisms are part of biogeochemical cycles. In addition to being a part of living organisms, these chemical elements also cycle through abiotic factors of ecosystems such as water (hydrosphere), land (lithosphere), and/or the air (atmosphere).[5]

The living factors of the planet can be referred to collectively as the biosphere. All the nutrients — such as carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur — used in ecosystems by living organisms are a part of a closed system; therefore, these chemicals are recycled instead of being lost and replenished constantly such as in an open system.[5]

The major parts of the biosphere are connected by the flow of chemical elements and compounds in biogeochemical cycles. In many of these cycles, the

The flow of energy in an ecosystem is an open system; the Sun constantly gives the planet energy in the form of light while it is eventually used and lost in the form of heat throughout the trophic levels of a food web. Carbon is used to make carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, the major sources of food energy. These compounds are oxidized to release carbon dioxide, which can be captured by plants to make organic compounds. The chemical reaction is powered by the light energy of sunshine.

Sunlight is required to combine carbon with hydrogen and oxygen into an energy source, but ecosystems in the

-

Examples of major biogeochemical processes

-

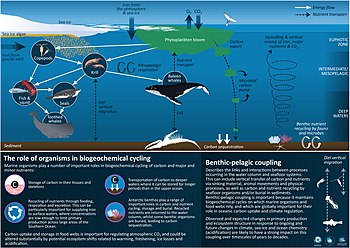

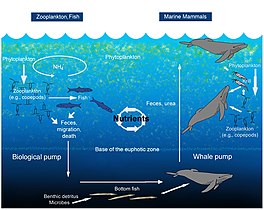

The oceanicwhale pump showing how whales cycle nutrients through the ocean water column

-

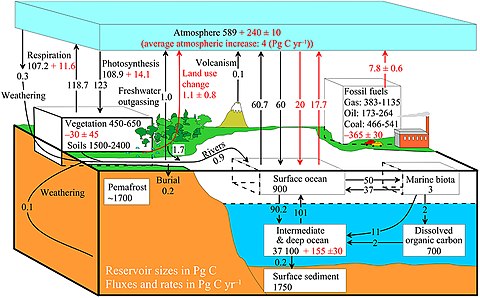

The implications of shifts in theglobal carbon cycle due to human activity are concerning scientists.[6]

Although the Earth constantly receives energy from the Sun, its chemical composition is essentially fixed, as the additional matter is only occasionally added by meteorites. Because this chemical composition is not replenished like energy, all processes that depend on these chemicals must be recycled. These cycles include both the living biosphere and the nonliving lithosphere, atmosphere, and hydrosphere.

Biogeochemical cycles can be contrasted with geochemical cycles. The latter deals only with crustal and subcrustal reservoirs even though some process from both overlap.

Compartments

Atmosphere

Hydrosphere

The global ocean covers more than 70% of the Earth's surface and is remarkably heterogeneous. Marine productive areas, and

Global change is, therefore, affecting key processes including

Lithosphere

Biosphere

Microorganisms drive much of the biogeochemical cycling in the earth system.[21][22]

Reservoirs

The chemicals are sometimes held for long periods of time in one place. This place is called a reservoir, which, for example, includes such things as coal deposits that are storing carbon for a long period of time.[23] When chemicals are held for only short periods of time, they are being held in exchange pools. Examples of exchange pools include plants and animals.[23]

Plants and animals utilize carbon to produce carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, which can then be used to build their internal structures or to obtain energy. Plants and animals temporarily use carbon in their systems and then release it back into the air or surrounding medium. Generally, reservoirs are abiotic factors whereas exchange pools are biotic factors. Carbon is held for a relatively short time in plants and animals in comparison to coal deposits. The amount of time that a chemical is held in one place is called its

Box models

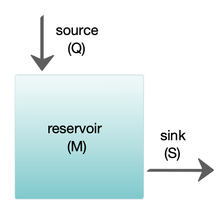

Box models are widely used to model biogeochemical systems.[24][25] Box models are simplified versions of complex systems, reducing them to boxes (or storage reservoirs) for chemical materials, linked by material fluxes (flows). Simple box models have a small number of boxes with properties, such as volume, that do not change with time. The boxes are assumed to behave as if they were mixed homogeneously.[25] These models are often used to derive analytical formulas describing the dynamics and steady-state abundance of the chemical species involved.

The diagram at the right shows a basic one-box model. The reservoir contains the amount of material M under consideration, as defined by chemical, physical or biological properties. The source Q is the flux of material into the reservoir, and the sink S is the flux of material out of the reservoir. The budget is the check and balance of the sources and sinks affecting material turnover in a reservoir. The reservoir is in a steady state if Q = S, that is, if the sources balance the sinks and there is no change over time.[25]

The residence or turnover time is the average time material spends resident in the reservoir. If the reservoir is in a steady state, this is the same as the time it takes to fill or drain the reservoir. Thus, if τ is the turnover time, then τ = M/S.[25] The equation describing the rate of change of content in a reservoir is

When two or more reservoirs are connected, the material can be regarded as cycling between the reservoirs, and there can be predictable patterns to the cyclic flow.[25] More complex multibox models are usually solved using numerical techniques.

Global biogeochemical box models usually measure:

- reservoir masses in

petagrams(Pg)- flow fluxes in petagrams per year (Pg yr−1)

The diagram on the left shows a simplified budget of ocean carbon flows. It is composed of three simple interconnected box models, one for the

The diagram on the right shows a more complex model with many interacting boxes. Reservoir masses here represents carbon stocks, measured in Pg C. Carbon exchange fluxes, measured in Pg C yr−1, occur between the atmosphere and its two major sinks, the land and the ocean. The black numbers and arrows indicate the reservoir mass and exchange fluxes estimated for the year 1750, just before the Industrial Revolution. The red arrows (and associated numbers) indicate the annual flux changes due to anthropogenic activities, averaged over the 2000–2009 time period. They represent how the carbon cycle has changed since 1750. Red numbers in the reservoirs represent the cumulative changes in anthropogenic carbon since the start of the Industrial Period, 1750–2011.[28][29][27]

Fast and slow cycles

There are fast and slow biogeochemical cycles. Fast cycle operate in the biosphere and slow cycles operate in rocks. Fast or biological cycles can complete within years, moving substances from atmosphere to biosphere, then back to the atmosphere. Slow or geological cycles can take millions of years to complete, moving substances through the Earth's crust between rocks, soil, ocean and atmosphere.[31]

As an example, the fast carbon cycle is illustrated in the diagram below on the left. This cycle involves relatively short-term

The slow cycle is illustrated in the diagram above on the right. It involves medium to long-term

Deep cycles

The terrestrial subsurface is the largest reservoir of carbon on earth, containing 14–135

Some examples

Some of the more well-known biogeochemical cycles are shown below:

Many biogeochemical cycles are currently being studied for the first time. Climate change and human impacts are drastically changing the speed, intensity, and balance of these relatively unknown cycles, which include:

- the mercury cycle,[49] and

- the human-caused cycle of PCBs.[50]

-

organisms.

-

Coal is a reservoir of carbon

Biogeochemical cycles always involve active equilibrium states: a balance in the cycling of the element between compartments. However, overall balance may involve compartments distributed on a global scale.

As biogeochemical cycles describe the movements of substances on the entire globe, the study of these is inherently multidisciplinary. The carbon cycle may be related to research in

See also

- Carbonate–silicate cycle

- Ecological recycling

- Great Acceleration

- Hydrogen cycle

- Redox gradient

References

- ^ "CK12-Foundation". flexbooks.ck12.org. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ a b Moses, M. (2012) Biogeochemical cycles Archived 2021-11-22 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopedia of Earth.

- ^ Biogeochemical Cycles Archived 2021-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, OpenStax, 9 May 2019.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Fisher M. R. (Ed.) (2019) Environmental Biology, 3.2 Biogeochemical Cycles Archived 2021-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, OpenStax.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b "Biogeochemical Cycles". The Environmental Literacy Council. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- doi:10.1186/s13021-017-0077-x..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine - hdl:11336/128446..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine - S2CID 25888475.

- ^ doi:10.3389/fmars.2019.00657..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Galton, D. (1884) 10th Meeting: report of the royal commission on metropolitan sewage Archived 2021-09-24 at the Wayback Machine. J. Soc. Arts, 33: 290.

- JSTOR 1294478.

- S2CID 5158406.

- S2CID 131163837.

- S2CID 24002134.

- ^ S2CID 206657115.

- ^ PMID 31213707.

- ^ S2CID 155102440.

- S2CID 13071345.

- S2CID 52811177.

- S2CID 6630698.

- S2CID 2844984.

- PMID 33173062..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine - ^ a b c Baedke, Steve J.; Fichter, Lynn S. "Biogeochemical Cycles: Carbon Cycle". Supplemental Lecture Notes for Geol 398. James Madison University. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- S2CID 4312683.

- ^ ISBN 9780195160826.

- ^ doi:10.1007/978-3-030-10822-9..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine - ^ S2CID 30408500..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine - S2CID 128553441.

- .

- ^ Riebeek, Holli (16 June 2011). "The Carbon Cycle". Earth Observatory. NASA. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ ISBN 9781136294822.

- ^ from the original on 2021-09-27. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- PMID 11904360.

- doi:10.3390/sci1010017..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine - from the original on 2021-11-22. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- S2CID 9491320.

- PMID 22927371.

- PMID 27190214.

- PMID 27417261.

- PMID 26180552.

- PMID 22092293.

- ^ from the original on 2021-09-27. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- PMID 20807744.

- PMID 26621749.

- S2CID 3983278.

- PMID 26500826.

- S2CID 24696869.

- PMID 27774985..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine - ^ "Mercury Cycling in the Environment". Wisconsin Water Science Center. United States Geological Survey. 10 January 2013. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ISBN 9782759200139.

- S2CID 205243485.

- .

- ^ McGuire, 1A. D.; Lukina, N. V. (2007). "Biogeochemical cycles" (PDF). In Groisman, P.; Bartalev, S. A.; NEESPI Science Plan Development Team (eds.). Northern Eurasia earth science partnership initiative (NEESPI), Science plan overview. Global Planetary Change. Vol. 56. pp. 215–234. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Distributed Active Archive Center for Biogeochemical Dynamics". daac.ornl.gov. Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

Further reading

- Schink, Bernhard; "Microbes: Masters of the Global Element Cycles" pp 33–58. "Metals, Microbes and Minerals: The Biogeochemical Side of Life", pp xiv + 341. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin. DOI 10.1515/9783110589771-002

- Butcher, Samuel S., ed. (1993). Global biogeochemical cycles. London: Academic Press. ISBN 9780080954707.

- Exley, C (15 September 2003). "A biogeochemical cycle for aluminium?". Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 97 (1): 1–7. PMID 14507454.

- Jacobson, Michael C.; Charlson, Robert J.; Rodhe, Henning; Orians, Gordon H. (2000). Earth system science from biogeochemical cycles to global change (2nd ed.). San Diego, Calif.: Academic Press. ISBN 9780080530642.

- Palmeri, Luca; Barausse, Alberto; Jorgensen, Sven Erik (2013). "12. Biogeochemical cycles". Ecological processes handbook. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781466558489.

![The implications of shifts in the global carbon cycle due to human activity are concerning scientists.[6]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/af/Global_carbon_cycle.webp/364px-Global_carbon_cycle.webp.png)

![Kerogen cycle[51][52]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/21/Organic_carbon_cycle_including_the_flow_of_kerogen.png/348px-Organic_carbon_cycle_including_the_flow_of_kerogen.png)