Biomineralization

| Part of a series related to |

| Biomineralization |

|---|

|

Biomineralization: Complete conversion of organic substances to inorganic derivatives by living organisms, especially micro-organisms.[1]

Biomineralization, also written biomineralisation, is the process by which living

Organisms have been producing mineralized skeletons for the past 550 million years. Calcium carbonates and calcium phosphates are usually crystalline, but silica organisms (sponges, diatoms...) are always non-crystalline minerals. Other examples include copper, iron, and gold deposits involving bacteria. Biologically formed minerals often have special uses such as magnetic sensors in magnetotactic bacteria (Fe3O4), gravity-sensing devices (CaCO3, CaSO4, BaSO4) and iron storage and mobilization (Fe2O3•H2O in the protein ferritin).

In terms of taxonomic distribution, the most common biominerals are the

Types

Mineralization can be subdivided into different categories depending on the following: the organisms or processes that create chemical conditions necessary for mineral formation, the origin of the substrate at the site of mineral precipitation, and the degree of control that the substrate has on crystal morphology, composition, and growth.[8] These subcategories include biomineralization, organomineralization, and inorganic mineralization, which can be subdivided further. However, the usage of these terms varies widely in the scientific literature because there are no standardized definitions. The following definitions are based largely on a paper written by Dupraz et al. (2009),[8] which provided a framework for differentiating these terms.

Biomineralization

Biomineralization, biologically controlled mineralization, occurs when crystal morphology, growth, composition, and location are completely controlled by the cellular processes of a specific organism. Examples include the shells of invertebrates, such as molluscs and brachiopods. Additionally, the mineralization of collagen provides crucial compressive strength for the bones, cartilage, and teeth of vertebrates.[9]

Organomineralization

This type of mineralization includes both biologically induced mineralization and biologically influenced mineralization.

- Biologically induced mineralization occurs when the metabolic activity of microbes (e.g. bacteria) produces chemical conditions favorable for mineral formation. The substrate for mineral growth is the organic matrix, secreted by the microbial community, and affects crystal morphology and composition. Examples of this type of mineralization include calcareous or siliceous stromatolites and other microbial mats. A more specific type of biologically induced mineralization, remote calcification or remote mineralization, takes place when calcifying microbes occupy a shell-secreting organism and alter the chemical environment surrounding the area of shell formation. The result is mineral formation not strongly controlled by the cellular processes of the animal host (i.e., remote mineralization); this may lead to unusual crystal morphologies.[10]

- Biologically influenced mineralization takes place when chemical conditions surrounding the site of mineral formation are influenced by abiotic processes (e.g., evaporation or degassing). However, the organic matrix (secreted by microorganisms) is responsible for crystal morphology and composition. Examples include micro- to nanometer-scale crystals of various morphologies.[11][12]

Biological mineralization can also take place as a result of fossilization. See also calcification.

Biological roles

Among animals, biominerals composed of

-

Many protists, like this coccolithophore, have protective mineralised shells

-

Foramsfrom a beach

-

Many invertebrate animals have external exoskeletons or shells, which achieve rigidity by a variety of mineralisations

-

Vertebrate animals have internalhydroxylapatite

If present on a supracellular scale, biominerals are usually deposited by a dedicated organ, which is often defined very early in embryological development. This organ will contain an organic matrix that facilitates and directs the deposition of crystals.

In molluscs

The mollusc shell is a biogenic composite material that has been the subject of much interest in materials science because of its unusual properties and its model character for biomineralization. Molluscan shells consist of 95–99% calcium carbonate by weight, while an organic component makes up the remaining 1–5%. The resulting composite has a fracture toughness ≈3000 times greater than that of the crystals themselves.[15] In the biomineralization of the mollusc shell, specialized proteins are responsible for directing crystal nucleation, phase, morphology, and growths dynamics and ultimately give the shell its remarkable mechanical strength. The application of biomimetic principles elucidated from mollusc shell assembly and structure may help in fabricating new composite materials with enhanced optical, electronic, or structural properties.[citation needed]

The most described arrangement in mollusc shells is the nacre, known in large shells such as Pinna or the pearl oyster (Pinctada). Not only does the structure of the layers differ, but so do their mineralogy and chemical composition. Both contain organic components (proteins, sugars, and lipids), and the organic components are characteristic of the layer and of the species.[4] The structures and arrangements of mollusc shells are diverse, but they share some features: the main part of the shell is crystalline calcium carbonate (aragonite, calcite), though some amorphous calcium carbonate occurs as well; and although they react as crystals, they never show angles and facets.[16]

In fungi

(b) Fungi as heterotrophs, recycle organic matter

(c) CO2 produced by heterotrophic fungal respiration can dissolve into H2O and depending on the physicochemical conditions precipitate as CaCO3 leading to the formation of a secondary mineral.

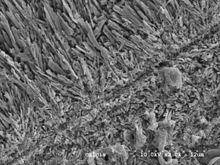

Fungi are a diverse group of organisms that belong to the eukaryotic domain. Studies of their significant roles in geological processes, "geomycology", have shown that fungi are involved with biomineralization, biodegradation, and metal-fungal interactions.[18]

In studying fungi's roles in biomineralization, it has been found that fungi deposit minerals with the help of an organic matrix, such as a protein, that provides a nucleation site for the growth of biominerals.

In addition to precipitating carbonate minerals, fungi can also precipitate

Though minerals can be produced by fungi, they can also be degraded, mainly by oxalic acid–producing strains of fungi.[21] Oxalic acid production is increased in the presence of glucose for three organic acid producing fungi: Aspergillus niger, Serpula himantioides, and Trametes versicolor.[21] These fungi have been found to corrode apatite and galena minerals.[21] Degradation of minerals by fungi is carried out through a process known as neogenesis.[22] The order of most to least oxalic acid secreted by the fungi studied are Aspergillus niger, followed by Serpula himantioides, and finally Trametes versicolor.[21]

In bacteria

It is less clear what purpose biominerals serve in bacteria. One hypothesis is that cells create them to avoid entombment by their own metabolic byproducts. Iron oxide particles may also enhance their metabolism.[23]

Other roles

Biomineralization plays significant global roles

Composition

Most biominerals can be grouped by chemical composition into one of three distinct mineral classes: silicates, carbonates, or phosphates.[25]

Silicates

Silicates (glass) are common in marine biominerals, where diatoms and radiolaria form frustules from hydrated amorphous silica (opal).[27]

Carbonates

The major carbonate in biominerals is CaCO3. The most common polymorphs in biomineralization are calcite (e.g. foraminifera, coccolithophores) and aragonite (e.g. corals), although metastable vaterite and amorphous calcium carbonate can also be important, either structurally[28][29] or as intermediate phases in biomineralization.[30][31] Some biominerals include a mixture of these phases in distinct, organised structural components (e.g. bivalve shells). Carbonates are particularly prevalent in marine environments, but also present in freshwater and terrestrial organisms.[32]

Phosphates

The most common biogenic phosphate is

The clubbing appendages of the

| Composition | Example organisms |

|---|---|

| Calcium carbonate (calcite or aragonite) |

|

Silica /glass/opal)

(silicate |

|

| Apatite (phosphate minerals) |

|

Other minerals

Beyond these main three categories, there are a number of less common types of biominerals, usually resulting from a need for specific physical properties or the organism inhabiting an unusual environment. For example, teeth that are primarily used for scraping hard substrates may be reinforced with particularly tough minerals, such as the iron minerals magnetite in chitons[39] or goethite in limpets.[40] Gastropod molluscs living close to hydrothermal vents reinforce their carbonate shells with the iron-sulphur minerals pyrite and greigite.[41] Magnetotactic bacteria also employ magnetic iron minerals magnetite and greigite to produce magnetosomes to aid orientation and distribution in the sediments.

-

Limpets have carbonate shells and teeth reinforced with goethite

-

Acantharianradiolarians have celestine crystal shells

-

Celestine crystals, the heaviest mineral in the oceans

Diversity

In nature, there is a wide array of biominerals, ranging from iron oxide to strontium sulfate,

Broadly, biomineralized structures evolve and diversify when the energetic cost of biomineral production is less than the expense of producing an equivalent organic structure.[57][58][59] The energetic costs of forming a silica structure from silicic acid are much less than forming the same volume from an organic structure (≈20-fold less than lignin or 10-fold less than polysaccharides like cellulose).[60] Based on a structural model of biogenic silica,[61] Lobel et al. (1996) identified by biochemical modeling a low-energy reaction pathway for nucleation and growth of silica.[62] The combination of organic and inorganic components within biomineralized structures often results in enhanced properties compared to exclusively organic or inorganic materials. With respect to biogenic silica, this can result in the production of much stronger structures, such as siliceous diatom frustules having the highest strength per unit density of any known biological material,[63][64] or sponge spicules being many times more flexible than an equivalent structure made of pure silica.[65][66] As a result, biogenic silica structures are used for support,[67] feeding,[68] predation defense [69][70][71] and environmental protection as a component of cyst walls.[53] Biogenic silica also has useful optical properties for light transmission and modulation in organisms as diverse as plants,[72] diatoms,[73][74][75] sponges,[76] and molluscs.[77] There is also evidence that silicification is used as a detoxification response in snails [78] and plants,[79] biosilica has even been suggested to play a role as a pH buffer for the enzymatic activity of carbonic anhydrase, aiding the acquisition of inorganic carbon for photosynthesis.[80][56]

-

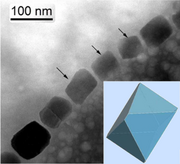

Diversity of biomineralization across the eukaryotes [56]The phylogeny shown in this diagram is based on Adl et al. (2012),[81] with major eukaryotic supergroups named in boxes. Letters next to taxon names denote the presence of biomineralization, with circled letters indicating the prominent and widespread use of that biomineral. S, silica; C, calcium carbonate; P, calcium phosphate; I, iron (magnetite/goethite); X, calcium oxalate; SO4, sulfates (calcium/barium/strontium), ? denotes uncertainty in the report.[82][83][25][50][47][84]

There are questions which have yet to be resolved, such as why some organisms biomineralize while others do not, and why is there such a diversity of biominerals besides silicon when silicon is so abundant, comprising 28% of the Earth's crust.[56] The answer to these questions lies in the evolutionary interplay between biomineralization and geochemistry, and in the competitive interactions that have arisen from these dynamics. Fundamentally whether an organism produces silica or not involves evolutionary trade-offs and competition between silicifiers themselves, and non-silicifying organisms (both those which use other biominerals, and non-mineralizing groups). Mathematical models and controlled experiments of resource competition in phytoplankton have demonstrated the rise to dominance of different algal species based on nutrient backgrounds in defined media. These have been part of fundamental studies in ecology.[85][86] However, the vast diversity of organisms that thrive in a complex array of biotic and abiotic interactions in oceanic ecosystems are a challenge to such minimal models and experimental designs, whose parameterization and possible combinations, respectively, limit the interpretations that can be built on them.[56]

Evolution

The first evidence of biomineralization dates to some 750 million years ago,

Biomineralization evolved multiple times, independently,

The homology of biomineralization pathways is underlined by a remarkable experiment whereby the nacreous layer of a molluscan shell was implanted into a human tooth, and rather than experiencing an immune response, the molluscan nacre was incorporated into the host bone matrix. This points to the exaptation of an original biomineralization pathway. The biomineralisation capacity of brachiopods and molluscs has also been demonstrated to be homologous, building on a conserved set of genes.[103] This indicates that biomineralisation is likely ancestral to all lophotrochozoans.

The most ancient example of biomineralization, dating back 2 billion years, is the deposition of

Potential applications

Most traditional approaches to the synthesis of nanoscale materials are energy inefficient, requiring stringent conditions (e.g., high temperature, pressure, or pH), and often produce toxic byproducts. Furthermore, the quantities produced are small, and the resultant material is usually irreproducible because of the difficulties in controlling agglomeration.[106] In contrast, materials produced by organisms have properties that usually surpass those of analogous synthetically manufactured materials with similar phase composition. Biological materials are assembled in aqueous environments under mild conditions by using macromolecules. Organic macromolecules collect and transport raw materials and assemble these substrates and into short- and long-range ordered composites with consistency and uniformity.[107][108]

The aim of biomimetics is to mimic the natural way of producing minerals such as apatites. Many man-made crystals require elevated temperatures and strong chemical solutions, whereas the organisms have long been able to lay down elaborate mineral structures at ambient temperatures. Often, the mineral phases are not pure but are made as composites that entail an organic part, often protein, which takes part in and controls the biomineralization. These composites are often not only as hard as the pure mineral but also tougher, as the micro-environment controls biomineralization.[107][108]

Architecture

One biological system that might be of key importance in the future development of architecture is bacterial biofilm. The term biofilm refers to complex heterogeneous structures comprising different populations of microorganisms that attach and form a community on inert (e.g. rocks, glass, plastic) or organic (e.g. skin, cuticle, mucosa) surfaces.[109]

The properties of the surface, such as charge,

-

Model for biomineralization‐mediated scaffoldingA directed growth of the calcium carbonate crystals allows mechanical support of the 3D structure. The bacterial extracellular matrix (brown) promotes the crystals' growth in specific directions.[115][114]

of bacterial biofilms

Bacterially induced calcium carbonate precipitation can be used to produce "self‐healing" concrete. Bacillus megaterium spores and suitable dried nutrients are mixed and applied to steel‐reinforced concrete. When the concrete cracks, water ingress dissolves the nutrients and the bacteria germinate triggering calcium carbonate precipitation, resealing the crack and protecting the steel reinforcement from corrosion.[116] This process can also be used to manufacture new hard materials, such as bio‐cement.[117][114]

However, the full potential of bacteria‐driven biomineralization is yet to be realized, as it is currently used as a passive filling rather than as a smart designable material. A future challenge is to develop ways to control the timing and the location of mineral formation, as well as the physical properties of the mineral itself, by environmental input. Bacillus subtilis has already been shown to respond to its environment, by changing the production of its ECM. It uses the polymers produced by single cells during biofilm formation as a physical cue to coordinate ECM production by the bacterial community.[118][119][114]

Uranium contaminants

-

Autunite crystal

Biomineralization may be used to remediate groundwater contaminated with uranium.[120] The biomineralization of uranium primarily involves the precipitation of uranium phosphate minerals associated with the release of phosphate by microorganisms. Negatively charged ligands at the surface of the cells attract the positively charged uranyl ion (UO22+). If the concentrations of phosphate and UO22+ are sufficiently high, minerals such as autunite (Ca(UO2)2(PO4)2•10-12H2O) or polycrystalline HUO2PO4 may form thus reducing the mobility of UO22+. Compared to the direct addition of inorganic phosphate to contaminated groundwater, biomineralization has the advantage that the ligands produced by microbes will target uranium compounds more specifically rather than react actively with all aqueous metals. Stimulating bacterial phosphatase activity to liberate phosphate under controlled conditions limits the rate of bacterial hydrolysis of organophosphate and the release of phosphate to the system, thus avoiding clogging of the injection location with metal phosphate minerals.[120] The high concentration of ligands near the cell surface also provides nucleation foci for precipitation, which leads to higher efficiency than chemical precipitation.[121]

Biogenic mineral controversy

The geological definition of mineral normally excludes compounds that occur only in living beings. However, some minerals are often

The International Mineralogical Association (IMA) is the generally recognized standard body for the definition and nomenclature of mineral species. As of December 2020[update], the IMA recognizes 5,650 official mineral species[122] out of 5,862 proposed or traditional ones.[123]

A topic of contention among geologists and mineralogists has been the IMA's decision to exclude biogenic crystalline substances. For example, Lowenstam (1981) stated that "organisms are capable of forming a diverse array of minerals, some of which cannot be formed inorganically in the biosphere."[124]

Skinner (2005) views all solids as potential minerals and includes biominerals in the mineral kingdom, which are those that are created by the metabolic activities of organisms. Skinner expanded the previous definition of a mineral to classify "element or compound, amorphous or crystalline, formed through biogeochemical processes," as a mineral.[125]

Recent advances in high-resolution genetics and X-ray absorption spectroscopy are providing revelations on the biogeochemical relations between microorganisms and minerals that may shed new light on this question.[126][125] For example, the IMA-commissioned "Working Group on Environmental Mineralogy and Geochemistry " deals with minerals in the hydrosphere, atmosphere, and biosphere.[127] The group's scope includes mineral-forming microorganisms, which exist on nearly every rock, soil, and particle surface spanning the globe to depths of at least 1,600 metres below the sea floor and 70 kilometres into the stratosphere (possibly entering the mesosphere).[128][129][130]

Prior to the International Mineralogical Association's listing, over 60 biominerals had been discovered, named, and published.[134] These minerals (a sub-set tabulated in Lowenstam (1981)[124]) are considered minerals proper according to Skinner's (2005) definition.[125] These biominerals are not listed in the International Mineral Association official list of mineral names,[135] however, many of these biomineral representatives are distributed amongst the 78 mineral classes listed in the Dana classification scheme.[125]

Skinner's (2005) definition of a mineral takes this matter into account by stating that a mineral can be crystalline or amorphous.[125] Although biominerals are not the most common form of minerals,[136] they help to define the limits of what constitutes a mineral properly. Nickel's (1995) formal definition explicitly mentioned crystallinity as a key to defining a substance as a mineral.[126] A 2011 article defined icosahedrite, an aluminium-iron-copper alloy as mineral; named for its unique natural icosahedral symmetry, it is a quasicrystal. Unlike a true crystal, quasicrystals are ordered but not periodic.[137][138]

List of minerals

Examples of biogenic minerals include:[139]

- Apatite in bones and teeth.

- Aragonite, calcite, fluorite in vestibular systems (part of the inner ear) of vertebrates.

- algalaction.

- mitochondria.

- Magnetite and greigite formed by magnetotactic bacteria.

- Pyrite and marcasite in sedimentary rocks deposited by sulfate-reducing bacteria.

- Quartz formed from bacterial action on fossil fuels (gas, oil, coal).

- Goethite found as filaments in limpet teeth.

Astrobiology

It has been suggested that biominerals could be important indicators of extraterrestrial life and thus could play an important role in the search for past or present life on

On 24 January 2014, NASA reported that current studies by the

See also

- Biocrystallization

- Biofilm

- Biointerface

- Biomineralising polychaetes

- Bone mineral

- Microbiologically induced calcite precipitation

- Mineralized tissues

- Susannah M. Porter history of biomineralization

Notes

- ^ The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry defines biomineralization as "mineralization caused by cell-mediated phenomena" and notes that it "is a process generally concomitant to biodegradation".[1]

References

- ^ S2CID 98107080.

- ISBN 978-0-470-03525-2.

- ISBN 978-0-19-504977-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-87473-1.

- PMID 24116035.

- S2CID 46004807.

- PMID 10588672.

- ^ .

- PMID 26144973.

- S2CID 67846463.

- ISSN 2075-163X.

- S2CID 230631843.

- ^ PMID 16987510.

- S2CID 10214928.

- PMID 10562511.

- OCLC 77036366.

- ^ PMID 24710095..

Modified material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Modified material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - PMID 17307120.

- ^ PMID 28799032.

- ^ S2CID 9699895.

- ^ S2CID 35004304.

- .

- S2CID 41179538.

- S2CID 214154330.

- ^ Dove PM, DeYoreo JJ, Weiner S (eds.). Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. Archived from the original(PDF) on 20 June 2010.

- S2CID 312009.

- ISBN 9780122274305.

- S2CID 118355403.

- PMID 21458575.

- PMID 29097678.

- PMID 28847944.

- S2CID 42962176.

- S2CID 2222515.

- from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- PMID 27695330.

- ^ PMID 25506416.

- from the original on 13 September 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- S2CID 206541609.

- ISBN 978-3-527-33882-5.

- PMID 25694539.

- ISSN 0260-1230.

- PMID 24324461.

- ^ "Weird Sea Mollusk Sports Hundreds of Eyes Made of Armor". Live Science. 19 November 2015. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ doi:10.3389/fmars.2019.00634..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - .

- S2CID 90349921.

- ^ S2CID 37809270.

- doi:10.2113/0540329.

- S2CID 83376982.

- ^ PMID 27729397.

- PMID 17306563.

- PMID 19883440.

- ^ S2CID 27698051.

- PMID 5404077.

- S2CID 84525482.

- ^ S2CID 12447257..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - ISBN 9780198508823.

- .

- S2CID 85218013.

- S2CID 86067386.

- S2CID 84200496.

- S2CID 84969529.

- S2CID 4336989.

- PMID 26858446.

- .

- PMID 26261346.

- PMID 17175169.

- S2CID 46840652.

- PMID 17081802.

- .

- .

- S2CID 16034220.

- S2CID 121002890.

- .

- PMID 26627680.

- S2CID 4426508.

- PMID 24966236.

- PMID 11891333.

- PMID 11314953.

- S2CID 206507070.

- PMID 23020233.

- PMID 27194462.

- PMID 22696477.

- PMID 16666741.

- JSTOR 1935608.

- .

- .

- S2CID 32229787.

- S2CID 13171894.

- S2CID 9515357.

- ^ doi:10.1130/G25094A.1. Archived from the original(PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- S2CID 27418253.

- S2CID 6694681.

- S2CID 45466684.

- .

- ^ S2CID 4348775.

- ^ PMID 19915030.

- PMID 11607630.

- PMID 6991017.

- PMID 6991017.

- PMID 19638240.

- S2CID 7042860.

- PMID 36123753.

- ^ Kirschvink JL, Hagadorn JW (2000). "10 A Grand Unified theory of Biomineralization.". In Bäuerlein E (ed.). The Biomineralisation of Nano- and Micro-Structures. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. pp. 139–150.

- PMID 6017357.

- ISBN 978-1-55899-181-1.

- ^ ISBN 9780470986318.

- ^ ISBN 9781782423560.

- S2CID 4430171.

- S2CID 978396.

- ^ PMID 15639628.

- PMID 25825428.

- PMID 28089324.

- ^ PMID 28815998..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - PMID 28721240..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - ISBN 9781402062506.

- ^ US 8728365, Dosier GK, "Methods for making construction material using enzyme producing bacteria", issued 2014, assigned to Biomason Inc.

- PMID 22882172.

- PMID 24296669.

- ^ .

- ISBN 978-1-55581-195-2.

- ^ Pasero M, et al. (November 2020). "The New IMA List of Minerals A Work in Progress" (PDF). The New IMA List of Minerals. IMA – CNMNC (Commission on New Minerals Nomenclature and Classification). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ "IMA Database of Mineral Properties/ RRUFF Project". Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- ^ PMID 7008198.

- ^ S2CID 232388764.

- ^ a b Nickel EH (1995). "The definition of a mineral". The Canadian Mineralogist. 33 (3): 689–90.

- ^ "Working Group on Environmental Mineralogy and Geochemistry". Commissions, working groups and committees. International Mineralogical Association. 3 August 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-139-49459-5.

- S2CID 23374807.

- PMID 19527292.

- S2CID 1235688.

- S2CID 19993145.

- S2CID 130343033.

- PMID 17800080.

- ^ "Official IMA list of mineral names" (PDF). uws.edu.au. March 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-3460-9.

- S2CID 101152220.

- ^ "Approved as new mineral" (PDF). Commission on New Minerals and Mineral Names. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2012.

- ^ Corliss WR (November–December 1989). "Biogenic Minerals". Science Frontiers. 66.

- Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group(MEPAG) - NASA. p. 72. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ PMID 24458635.

- ^ a b Various (24 January 2014). "Special Issue - Table of Contents - Exploring Martian Habitability". Science. 343: 345–452. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Various (24 January 2014). "Special Collection - Curiosity - Exploring Martian Habitability". Science. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- S2CID 52836398.

Further reading

- doi:10.1002/anie.199201531. Archived from the original(abstract) on 17 December 2012.

- Boskey AL (2003). "Biomineralization: an overview". Connective Tissue Research. 44 (Supplement 1): 5–9. PMID 12952166.

- Cuif JP, Sorauf JE (2001). "Biomineralization and diagenesis in the Scleractinia : part I, biomineralization". Bull. Tohoku Univ. Museum. 1: 144–151.

- Dauphin Y (2002). "Structures, organo mineral compositions and diagenetic changes in biominerals". Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science. 7 (1–2): 133–138. .

- Dauphin Y (2005). King RB (ed.). Biomineralization. Vol. 1. Wiley & Sons. pp. 391–404. )

- Kupriyanova EK, Vinn O, Taylor PD, Schopf JW, Kudryavtsev AB, Bailey-Brock J (2014). "Serpulids living deep: calcareous tubeworms beyond the abyss". Deep-Sea Research Part I. 90: 91–104. . Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- Lowenstam HA (March 1981). "Minerals formed by organisms". Science. 211 (4487): 1126–1131. S2CID 31036238.

- McPhee, Joseph (2006). "The Little Workers of the Mining Industry". Science Creative Quarterly (2). Retrieved 3 November 2006.

- Schmittner KE, Giresse P (1999). "Micro-environmental controls on biomineralization: superficial processes of apatite and calcite precipitation in Quaternary soils, Roussillon, France". Sedimentology. 46 (3): 463–476. S2CID 140680495.

- Uebe R, Schüler D (2021). "The Formation of Iron Biominerals". In Kroneck PM, Sosa Torres ME (eds.). Metals, Microbes, and Minerals - The Biogeochemical Side of Life. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 159–184. ISBN 978-3-11-058977-1.

- Vinn O (2013). "Occurrence, formation and function of organic sheets in the mineral tube structures of Serpulidae (polychaeta, Annelida)". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e75330. PMID 24116035.

- Vinn O, ten Hove HA, Mutvei H (2008). "Ultrastructure and mineral composition of serpulid tubes (Polychaeta, Annelida)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 154 (4): 633–650. . Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- Weiner S, doi:10.1039/a604512j.

External links

- 'Data and literature on modern and fossil Biominerals': http://biomineralisation.blogspot.fr

- An overview of the bacteria involved in biomineralization from the Science Creative Quarterly

- Biomineralization web-book: bio-mineral.org

- Minerals and the Origins of Life (Robert Hazen, NASA) (video, 60m, April 2014).

- Special German Research Project About the Principles of Biomineralization

![Chitons have aragonite shells and aragonite-based eyes,[43] as well as teeth coated with magnetite.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/39/Chitonidae_-_Chiton_squamosus.JPG/280px-Chitonidae_-_Chiton_squamosus.JPG)

![Diversity of biomineralization across the eukaryotes [56] The phylogeny shown in this diagram is based on Adl et al. (2012),[81] with major eukaryotic supergroups named in boxes. Letters next to taxon names denote the presence of biomineralization, with circled letters indicating the prominent and widespread use of that biomineral. S, silica; C, calcium carbonate; P, calcium phosphate; I, iron (magnetite/goethite); X, calcium oxalate; SO4, sulfates (calcium/barium/strontium), ? denotes uncertainty in the report.[82][83][25][50][47][84]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0f/Diversity_of_biomineralization_across_the_eukaryotes.jpg)

![Model for biomineralization‐mediated scaffolding of bacterial biofilms A directed growth of the calcium carbonate crystals allows mechanical support of the 3D structure. The bacterial extracellular matrix (brown) promotes the crystals' growth in specific directions.[115][114]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ee/Biomineralization%E2%80%90mediated_scaffolding_of_bacterial_biofilms.jpg/576px-Biomineralization%E2%80%90mediated_scaffolding_of_bacterial_biofilms.jpg)