Bipolar disorder

| Bipolar disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Bipolar affective disorder (BPAD), stress[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, personality disorders, schizophrenia, substance use disorder[4] |

| Treatment | Psychotherapy, medications[4] |

| Medication | Lithium, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants[4] |

| Frequency | 1–3%[4][6] |

Bipolar disorder, previously known as manic depression, is a mental disorder characterized by periods of depression and periods of abnormally elevated mood that each last from days to weeks.[4][5] If the elevated mood is severe or associated with psychosis, it is called mania; if it is less severe and does not significantly affect functioning, it is called hypomania.[4] During mania, an individual behaves or feels abnormally energetic, happy or irritable,[4] and they often make impulsive decisions with little regard for the consequences.[5] There is usually also a reduced need for sleep during manic phases.[5] During periods of depression, the individual may experience crying and have a negative outlook on life and poor eye contact with others.[4] The risk of suicide is high; over a period of 20 years, 6% of those with bipolar disorder died by suicide, while 30–40% engaged in self-harm.[4] Other mental health issues, such as anxiety disorders and substance use disorders, are commonly associated with bipolar disorder.[4]

While the causes of this

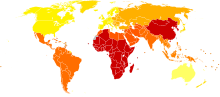

Bipolar disorder occurs in approximately 2% of the global population.

Signs and symptoms

Late adolescence and early adulthood are peak years for the onset of bipolar disorder.[21][22] The condition is characterized by intermittent episodes of mania, commonly (but not in every patient) alternating with bouts of depression, with an absence of symptoms in between.[23][24] During these episodes, people with bipolar disorder exhibit disruptions in normal mood, psychomotor activity (the level of physical activity that is influenced by mood)—e.g. constant fidgeting during mania or slowed movements during depression—circadian rhythm and cognition. Mania can present with varying levels of mood disturbance, ranging from euphoria, which is associated with "classic mania", to dysphoria and irritability.[25] Psychotic symptoms such as delusions or hallucinations may occur in both manic and depressive episodes; their content and nature are consistent with the person's prevailing mood.[4] In some people with bipolar disorder, depressive symptoms predominate, and the episodes of mania are always the more subdued hypomania type.[24]

According to the DSM-5 criteria, mania is distinguished from hypomania by the duration: hypomania is present if elevated mood symptoms persist for at least four consecutive days, while mania is present if such symptoms persist for more than a week. Unlike mania, hypomania is not always associated with impaired functioning.[12] The biological mechanisms responsible for switching from a manic or hypomanic episode to a depressive episode, or vice versa, remain poorly understood.[26]

Manic episodes

Also known as a manic episode, mania is a distinct period of at least one week of elevated or irritable mood, which can range from euphoria to

In severe manic episodes, a person can experience psychotic symptoms, where thought content is affected along with mood.[29] They may feel unstoppable, persecuted, or as if they have a special relationship with God, a great mission to accomplish, or other grandiose or delusional ideas.[31][32] This may lead to violent behavior and, sometimes, hospitalization in an inpatient psychiatric hospital.[28][29] The severity of manic symptoms can be measured by rating scales such as the Young Mania Rating Scale, though questions remain about the reliability of these scales.[33]

The onset of a manic or depressive episode is often foreshadowed by sleep disturbance.[34] Manic individuals often have a history of substance use disorder developed over years as a form of "self-medication".[35]

Hypomanic episodes

Hypomania may feel good to some individuals who experience it, though most people who experience hypomania state that the stress of the experience is very painful.[29] People with bipolar disorder who experience hypomania tend to forget the effects of their actions on those around them. Even when family and friends recognize mood swings, the individual will often deny that anything is wrong.[38] If not accompanied by depressive episodes, hypomanic episodes are often not deemed problematic unless the mood changes are uncontrollable or volatile.[36] Most commonly, symptoms continue for time periods from a few weeks to a few months.[39]

Depressive episodes

Symptoms of the depressive phase of bipolar disorder include persistent feelings of sadness, irritability or anger, loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities, excessive or inappropriate guilt, hopelessness, sleeping too much or not enough, changes in appetite and/or weight, fatigue, problems concentrating, self-loathing or feelings of worthlessness, and thoughts of death or suicide.[40] Although the DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing unipolar and bipolar episodes are the same, some clinical features are more common in the latter, including increased sleep, sudden onset and resolution of symptoms, significant weight gain or loss, and severe episodes after childbirth.[12]

The earlier the age of onset, the more likely the first few episodes are to be depressive.

Mixed affective episodes

In bipolar disorder, a

Problematic digital media use

In November 2018, Cyberpsychology published a systematic review and meta-analysis of 5 studies that found evidence for a relationship between problematic smartphone use and impulsivity traits.[44] In October 2020, the Journal of Behavioral Addictions published a systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 studies with 33,650 post-secondary student subjects that found that a weak-to-moderate positive association between mobile phone addiction and impulsivity.[45]

In April 2021, a meta-analysis of 3 studies comprising 9,142 subjects was presented at the International Conference on Big Data and Informatization Education that found that problematic internet use is a risk factor for bipolar disorder.[46] In December 2023, the Journal of Psychiatric Research published a meta-analysis of 24 studies with 18,859 subjects with a mean age of 18.4 years that found significant associations between problematic internet use and impulsivity.[47]Comorbid conditions

People with bipolar disorder often have other co-existing psychiatric conditions such as

Substance use disorder is a common comorbidity in bipolar disorder; the subject has been widely reviewed.[48][needs update][49]

Causes

The causes of bipolar disorder likely vary between individuals and the exact mechanism underlying the disorder remains unclear.

The cause of bipolar disorders overlaps with major depressive disorder. When defining concordance as the co-twins having either bipolar disorder or major depression, then the concordance rate rises to 67% in identical twins and 19% in fraternal twins.[53] The relatively low concordance between fraternal twins brought up together suggests that shared family environmental effects are limited, although the ability to detect them has been limited by small sample sizes.[51]

Genetic

Although the first

Due to the inconsistent findings in a

Bipolar disorder is associated with reduced expression of specific DNA repair enzymes and increased levels of oxidative DNA damages.[63]

Environmental

Neurological

Less commonly, bipolar disorder or a bipolar-like disorder may occur as a result of or in association with a neurological condition or injury including stroke, traumatic brain injury, HIV infection, multiple sclerosis, porphyria, and rarely temporal lobe epilepsy.[70]

Proposed mechanisms

The precise mechanisms that cause bipolar disorder are not well understood. Bipolar disorder is thought to be associated with abnormalities in the structure and function of certain brain areas responsible for cognitive tasks and the processing of emotions.[23] A neurologic model for bipolar disorder proposes that the emotional circuitry of the brain can be divided into two main parts.[23] The ventral system (regulates emotional perception) includes brain structures such as the amygdala, insula, ventral striatum, ventral anterior cingulate cortex, and the prefrontal cortex.[23] The dorsal system (responsible for emotional regulation) includes the hippocampus, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, and other parts of the prefrontal cortex.[23] The model hypothesizes that bipolar disorder may occur when the ventral system is overactivated and the dorsal system is underactivated.[23] Other models suggest the ability to regulate emotions is disrupted in people with bipolar disorder and that dysfunction of the ventricular prefrontal cortex is crucial to this disruption.[23]

Functional MRI findings suggest that the ventricular prefrontal cortex regulates the limbic system, especially the amygdala.[75] In people with bipolar disorder, decreased ventricular prefrontal cortex activity allows for the dysregulated activity of the amygdala, which likely contributes to labile mood and poor emotional regulation.[75] Consistent with this, pharmacological treatment of mania returns ventricular prefrontal cortex activity to the levels in non-manic people, suggesting that ventricular prefrontal cortex activity is an indicator of mood state. However, while pharmacological treatment of mania reduces amygdala hyperactivity, it remains more active than the amygdala of those without bipolar disorder, suggesting amygdala activity may be a marker of the disorder rather than the current mood state.[76] Manic and depressive episodes tend to be characterized by dysfunction in different regions of the ventricular prefrontal cortex. Manic episodes appear to be associated with decreased activation of the right ventricular prefrontal cortex whereas depressive episodes are associated with decreased activation of the left ventricular prefrontal cortex.[75] These disruptions often occur during development linked with synaptic pruning dysfunction.[77]

People with bipolar disorder who are in a

Neuroscientists have proposed additional models to try to explain the cause of bipolar disorder. One proposed model for bipolar disorder suggests that hypersensitivity of reward circuits consisting of

Dopamine, a neurotransmitter responsible for mood cycling, has increased transmission during the manic phase.[26][84] The dopamine hypothesis states that the increase in dopamine results in secondary homeostatic downregulation of key system elements and receptors such as lower sensitivity of dopaminergic receptors. This results in decreased dopamine transmission characteristic of the depressive phase.[26] The depressive phase ends with homeostatic upregulation potentially restarting the cycle over again.[85] Glutamate is significantly increased within the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during the manic phase of bipolar disorder, and returns to normal levels once the phase is over.[86]

Medications used to treat bipolar may exert their effect by modulating intracellular signaling, such as through depleting myo-

Decreased levels of

Diagnosis

Bipolar disorder is commonly diagnosed during adolescence or early adulthood, but onset can occur throughout life.[5][92] Its diagnosis is based on the self-reported experiences of the individual, abnormal behavior reported by family members, friends or co-workers, observable signs of illness as assessed by a clinician, and ideally a medical work-up to rule out other causes. Caregiver-scored rating scales, specifically from the mother, have shown to be more accurate than teacher and youth-scored reports in identifying youths with bipolar disorder.[93] Assessment is usually done on an outpatient basis; admission to an inpatient facility is considered if there is a risk to oneself or others.

The most widely used criteria for diagnosing bipolar disorder are from the

Several

Differential diagnosis

Bipolar disorder is classified by the

Although there are no biological tests that are diagnostic of bipolar disorder,

Bipolar spectrum

Bipolar spectrum disorders include: bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, cyclothymic disorder and cases where subthreshold symptoms are found to cause clinically significant impairment or distress.[5][92][95] These disorders involve major depressive episodes that alternate with manic or hypomanic episodes, or with mixed episodes that feature symptoms of both mood states.[5] The concept of the bipolar spectrum is similar to that of Emil Kraepelin's original concept of manic depressive illness.[105] Bipolar II disorder was established as a diagnosis in 1994 within DSM IV; though debate continues over whether it is a distinct entity, part of a spectrum, or exists at all.[106]

Criteria and subtypes

The DSM and the ICD characterize bipolar disorder as a spectrum of disorders occurring on a continuum. The DSM-5 and ICD-11 lists three specific subtypes:[5][95]

- Bipolar I disorder: At least one manic episode is necessary to make the diagnosis;[109] depressive episodes are common in the vast majority of cases with bipolar disorder I, but are unnecessary for the diagnosis.[27] Specifiers such as "mild, moderate, moderate-severe, severe" and "with psychotic features" should be added as applicable to indicate the presentation and course of the disorder.[5]

- Bipolar II disorder: No manic episodes and one or more hypomanic episodes and one or more major depressive episodes.[109] Hypomanic episodes do not go to the full extremes of mania (i.e., do not usually cause severe social or occupational impairment, and are without psychosis), and this can make bipolar II more difficult to diagnose, since the hypomanic episodes may simply appear as periods of successful high productivity and are reported less frequently than a distressing, crippling depression.

- Cyclothymia: A history of hypomanic episodes with periods of depression that do not meet criteria for major depressive episodes.[10]

When relevant, specifiers for peripartum onset and with rapid cycling should be used with any subtype. Individuals who have subthreshold symptoms that cause clinically significant distress or impairment, but do not meet full criteria for one of the three subtypes may be diagnosed with other specified or unspecified bipolar disorder. Other specified bipolar disorder is used when a clinician chooses to explain why the full criteria were not met (e.g., hypomania without a prior major depressive episode).[5] If the condition is thought to have a non-psychiatric medical cause, the diagnosis of bipolar and related disorder due to another medical condition is made, while substance/medication-induced bipolar and related disorder is used if a medication is thought to have triggered the condition.[110]

Rapid cycling

Most people who meet criteria for bipolar disorder experience a number of episodes, on average 0.4 to 0.7 per year, lasting three to six months.[111] Rapid cycling, however, is a course specifier that may be applied to any bipolar subtype. It is defined as having four or more mood disturbance episodes within a one-year span. Rapid cycling is usually temporary but is common amongst people with bipolar disorder and affects 25.8–45.3% of them at some point in their life.[40][112] These episodes are separated from each other by a remission (partial or full) for at least two months or a switch in mood polarity (i.e., from a depressive episode to a manic episode or vice versa).[27] The definition of rapid cycling most frequently cited in the literature (including the DSM-V and ICD-11) is that of Dunner and Fieve: at least four major depressive, manic, hypomanic or mixed episodes during a 12-month period.[113] The literature examining the pharmacological treatment of rapid cycling is sparse and there is no clear consensus with respect to its optimal pharmacological management.[114] People with the rapid cycling or ultradian subtypes of bipolar disorder tend to be more difficult to treat and less responsive to medications than other people with bipolar disorder.[115]

Coexisting psychiatric conditions

The diagnosis of bipolar disorder can be complicated by coexisting (comorbid) psychiatric conditions including obsessive–compulsive disorder, substance-use disorder, eating disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, social phobia, premenstrual syndrome (including premenstrual dysphoric disorder), or panic disorder.[35][40][54][116] A thorough longitudinal analysis of symptoms and episodes, assisted if possible by discussions with friends and family members, is crucial to establishing a treatment plan where these comorbidities exist.[117] Children of parents with bipolar disorder more frequently have other mental health problems.[needs update][118]

Children

In the 1920s, Kraepelin noted that manic episodes are rare before puberty.

Adults

Bipolar on average, starts during adulthood. Bipolar 1, on average, starts at the age of 18 years old, and Bipolar 2 starts at age 22 years old on average. However, most delay seeking treatment for an average of 8 years after symptoms start. Bipolar is often misdiagnosed with other psychiatric disorders. There is no definitive association between race, ethnicity, or Socioeconomic status (SES).[124] Adults with Bipolar report having a lower quality of life, even outside of a manic or depressive episode. Bipolar can put strain on marriage and other relationships, having a job, and everyday functioning. Bipolar is associated with having higher rates of unemployment. Most have trouble keeping a job, leading to trouble with healthcare access, leading to more decline in their mental health due to not receiving treatment such as medicine and therapy.[125]

Elderly

Bipolar disorder is uncommon in older patients, with a measured lifetime prevalence of 1% in over 60s and a 12-month prevalence of 0.1–0.5% in people over 65. Despite this, it is overrepresented in psychiatric admissions, making up 4–8% of inpatient admission to aged care psychiatry units, and the incidence of mood disorders is increasing overall with the aging population. Depressive episodes more commonly present with sleep disturbance, fatigue, hopelessness about the future, slowed thinking, and poor concentration and memory; the last three symptoms are seen in what is known as pseudodementia. Clinical features also differ between those with late-onset bipolar disorder and those who developed it early in life; the former group present with milder manic episodes, more prominent cognitive changes and have a background of worse psychosocial functioning, while the latter present more commonly with mixed affective episodes,[126] and have a stronger family history of illness.[127] Older people with bipolar disorder experience cognitive changes, particularly in executive functions such as abstract thinking and switching cognitive sets, as well as concentrating for long periods and decision-making.[126]

Prevention

Attempts at prevention of bipolar disorder have focused on stress (such as childhood adversity or highly conflictual families) which, although not a diagnostically specific causal agent for bipolar, does place genetically and biologically vulnerable individuals at risk for a more severe course of illness.[128] Longitudinal studies have indicated that full-blown manic stages are often preceded by a variety of prodromal clinical features, providing support for the occurrence of an at-risk state of the disorder when an early intervention might prevent its further development and/or improve its outcome.[129][130]

Management

The aim of management is to treat acute episodes safely with medication and work with the patient in long-term maintenance to prevent further episodes and optimise function using a combination of

Psychosocial

Medication

Medications are often prescribed to help improve symptoms of bipolar disorder. Medications approved for treating bipolar disorder including mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, and antidepressants. Sometimes a combination of medications may also be suggested.[12] The choice of medications may differ depending on the bipolar disorder episode type or if the person is experiencing unipolar or bipolar depression.[12][138] Other factors to consider when deciding on an appropriate treatment approach includes if the person has any comorbidities, their response to previous therapies, adverse effects, and the desire of the person to be treated.[12]

Mood stabilizers

Lithium and the

Mood stabilizers are used for long-term maintenance but have not demonstrated the ability to quickly treat acute bipolar depression.[115]

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotic medications are effective for short-term treatment of bipolar manic episodes and appear to be superior to lithium and anticonvulsants for this purpose.[65] Atypical antipsychotics are also indicated for bipolar depression refractory to treatment with mood stabilizers.[115] Olanzapine is effective in preventing relapses, although the supporting evidence is weaker than the evidence for lithium.[148] A 2006 review found that haloperidol was an effective treatment for acute mania, limited data supported no difference in overall efficacy between haloperidol, olanzapine or risperidone, and that it could be less effective than aripiprazole.[149]

Antidepressants

Combined treatment approaches

Antipsychotics and mood stabilizers used together are quicker and more effective at treating mania than either class of drug used alone. Some analyses indicate antipsychotics alone are also more effective at treating acute mania.[12] A first-line treatment for depression in bipolar disorder is a combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine.[138]

Other drugs

Short courses of

Children

Treating bipolar disorder in children involves medication and psychotherapy.[121] The literature and research on the effects of psychosocial therapy on bipolar spectrum disorders are scarce, making it difficult to determine the efficacy of various therapies.[155] Mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics are commonly prescribed.[121] Among the former, lithium is the only compound approved by the FDA for children.[119] Psychological treatment combines normally education on the disease, group therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy.[121] Long-term medication is often needed.[121]

Resistance to treatment

The occurrence of poor response to treatment in has given support to the concept of resistance to treatment in bipolar disorder.[156][157] Guidelines to the definition of such treatment resistance and evidence-based options for its management were reviewed in 2020.[158]

Management of obesity

A large proportion (approximately 68%) of people who seek treatment for bipolar disorder are obese or overweight and managing obesity is important for reducing the risk of other health conditions that are associated with obesity.[159] Management approaches include non-pharmacological, pharmacological, and surgical. Examples of non-pharmacological include dietary interventions, exercise, behavioral therapies, or combined approaches. Pharmacological approaches include weight-loss medications or changing medications already being prescribed.[160] Some people with bipolar disorder who have obesity may also be eligible for bariatric surgery.[159] The effectiveness of these various approaches to improving or managing obesity in people with bipolar disorder is not clear.[159]

Prognosis

A lifelong condition with periods of partial or full recovery in between recurrent episodes of relapse,

Compliance with medications is one of the most significant factors that can decrease the rate and severity of relapse and have a positive impact on overall prognosis.[164] However, the types of medications used in treating BD commonly cause side effects[165] and more than 75% of individuals with BD inconsistently take their medications for various reasons.[164] Of the various types of the disorder, rapid cycling (four or more episodes in one year) is associated with the worst prognosis due to higher rates of self-harm and suicide.[40] Individuals diagnosed with bipolar who have a family history of bipolar disorder are at a greater risk for more frequent manic/hypomanic episodes.[166] Early onset and psychotic features are also associated with worse outcomes,[167][168] as well as subtypes that are nonresponsive to lithium.[163]

Early recognition and intervention also improve prognosis as the symptoms in earlier stages are less severe and more responsive to treatment.[163] Onset after adolescence is connected to better prognoses for both genders, and being male is a protective factor against higher levels of depression. For women, better social functioning before developing bipolar disorder and being a parent are protective towards suicide attempts.[166]

Functioning

Changes in cognitive processes and abilities are seen in mood disorders, with those of bipolar disorder being greater than those in major depressive disorder.[169] These include reduced attentional and executive capabilities and impaired memory.[170] People with bipolar disorder often experience a decline in cognitive functioning during (or possibly before) their first episode, after which a certain degree of cognitive dysfunction typically becomes permanent, with more severe impairment during acute phases and moderate impairment during periods of remission. As a result, two-thirds of people with BD continue to experience impaired psychosocial functioning in between episodes even when their mood symptoms are in full remission. A similar pattern is seen in both BD-I and BD-II, but people with BD-II experience a lesser degree of impairment.[165]

When bipolar disorder occurs in children, it severely and adversely affects their psychosocial development.[122] Children and adolescents with bipolar disorder have higher rates of significant difficulties with substance use disorders, psychosis, academic difficulties, behavioral problems, social difficulties, and legal problems.[122] Cognitive deficits typically increase over the course of the illness. Higher degrees of impairment correlate with the number of previous manic episodes and hospitalizations, and with the presence of psychotic symptoms.[171] Early intervention can slow the progression of cognitive impairment, while treatment at later stages can help reduce distress and negative consequences related to cognitive dysfunction.[163]

Despite the overly ambitious goals that are frequently part of manic episodes, symptoms of mania undermine the ability to achieve these goals and often interfere with an individual's social and occupational functioning. One-third of people with BD remain unemployed for one year following a hospitalization for mania.[172] Depressive symptoms during and between episodes, which occur much more frequently for most people than hypomanic or manic symptoms over the course of illness, are associated with lower functional recovery in between episodes, including unemployment or underemployment for both BD-I and BD-II.[5][173] However, the course of illness (duration, age of onset, number of hospitalizations, and the presence or not of rapid cycling) and cognitive performance are the best predictors of employment outcomes in individuals with bipolar disorder, followed by symptoms of depression and years of education.[173]

Recovery and recurrence

A naturalistic study in 2003 by Tohen and coworkers from the first admission for mania or mixed episode (representing the hospitalized and therefore most severe cases) found that 50% achieved syndromal recovery (no longer meeting criteria for the diagnosis) within six weeks and 98% within two years. Within two years, 72% achieved symptomatic recovery (no symptoms at all) and 43% achieved functional recovery (regaining of prior occupational and residential status). However, 40% went on to experience a new episode of mania or depression within 2 years of syndromal recovery, and 19% switched phases without recovery.[174]

Symptoms preceding a relapse (

Suicide

Bipolar disorder can cause suicidal ideation that leads to suicide attempts. Individuals whose bipolar disorder begins with a depressive or mixed affective episode seem to have a poorer prognosis and an increased risk of suicide.[99] One out of two people with bipolar disorder attempt suicide at least once during their lifetime and many attempts are successfully completed.[54] The annual average suicide rate is 0.4%-1.4%, which is 30 to 60 times greater than that of the general population.[16] The number of deaths from suicide in bipolar disorder is between 18 and 25 times higher than would be expected in similarly aged people without bipolar disorder.[177] The lifetime risk of suicide is much higher in those with bipolar disorder, with an estimated 34% of people attempting suicide and 15–20% dying by suicide.[16]

Risk factors for suicide attempts and death from suicide in people with bipolar disorder include older age, prior suicide attempts, a depressive or mixed index episode (first episode), a manic index episode with psychotic symptoms, hopelessness or psychomotor agitation present during the episodes, co-existing anxiety disorder, a first degree relative with a mood disorder or suicide, interpersonal conflicts, occupational problems, bereavement or social isolation.[18]

Epidemiology

Bipolar disorder is the sixth leading cause of disability worldwide and has a lifetime prevalence of about 1 to 3% in the general population.

There are conceptual and methodological limitations and variations in the findings. Prevalence studies of bipolar disorder are typically carried out by lay interviewers who follow fully structured/fixed interview schemes; responses to single items from such interviews may have limited validity. In addition, diagnoses (and therefore estimates of prevalence) vary depending on whether a categorical or

The incidence of bipolar disorder is similar in men and women

History

In the early 1800s, French psychiatrist Jean-Étienne Dominique Esquirol's lypemania, one of his affective monomanias, was the first elaboration on what was to become modern depression.[188] The basis of the current conceptualization of bipolar illness can be traced back to the 1850s. In 1850, Jean-Pierre Falret described "circular insanity" (la folie circulaire, French pronunciation: [la fɔli siʁ.ky.lɛʁ]); the lecture was summarized in 1851 in the Gazette des hôpitaux ("Hospital Gazette").[2] Three years later, in 1854, Jules-Gabriel-François Baillarger (1809–1890) described to the French Imperial Académie Nationale de Médecine a biphasic mental illness causing recurrent oscillations between mania and melancholia, which he termed la folie à double forme (French pronunciation: [la fɔli a dubl fɔʀm], "madness in double form").[2][189] Baillarger's original paper, "De la folie à double forme", appeared in the medical journal Annales médico-psychologiques (Medico-psychological annals) in 1854.[2]

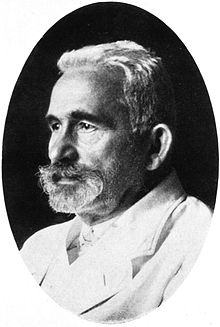

These concepts were developed by the German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926), who, using Kahlbaum's concept of cyclothymia,[190] categorized and studied the natural course of untreated bipolar patients. He coined the term manic depressive psychosis, after noting that periods of acute illness, manic or depressive, were generally punctuated by relatively symptom-free intervals where the patient was able to function normally.[191]

The term "manic–depressive reaction" appeared in the first version of the DSM in 1952, influenced by the legacy of Adolf Meyer.[192] Subtyping into "unipolar" depressive disorders and bipolar disorders has its origin in Karl Kleist's concept – since 1911 – of unipolar and bipolar affective disorders, which was used by Karl Leonhard in 1957 to differentiate between unipolar and bipolar disorder in depression.[193] These subtypes have been regarded as separate conditions since publication of the DSM-III. The subtypes bipolar II and rapid cycling have been included since the DSM-IV, based on work from the 1970s by David Dunner, Elliot Gershon, Frederick Goodwin, Ronald Fieve, and Joseph Fleiss.[194][195][196]

Society and culture

Cost

The United States spent approximately $202.1 billion on people diagnosed with bipolar I disorder (excluding other subtypes of bipolar disorder and undiagnosed people) in 2015.[162] One analysis estimated that the United Kingdom spent approximately £5.2 billion on the disorder in 2007.[198][199] In addition to the economic costs, bipolar disorder is a leading cause of disability and lost productivity worldwide.[20] People with bipolar disorder are generally more disabled, have a lower level of functioning, longer duration of illness, and increased rates of work absenteeism and decreased productivity when compared to people experiencing other mental health disorders.[200] The decrease in the productivity seen in those who care for people with bipolar disorder also significantly contributes to these costs.[201]

Advocacy

There are widespread issues with social stigma, stereotypes, and prejudice against individuals with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.[202] In 2000, actress Carrie Fisher went public with her bipolar disorder diagnosis.[203][204] She became one of the most well-recognized advocates for people with bipolar disorder in the public eye and fiercely advocated to eliminate the stigma surrounding mental illnesses, including bipolar disorder.[205] Stephen Fried, who has written extensively on the topic, noted that Fisher helped to draw attention to the disorder's chronicity, relapsing nature, and that bipolar disorder relapses do not indicate a lack of discipline or moral shortcomings.[205] Since being diagnosed at age 37, actor Stephen Fry has pushed to raise awareness of the condition, with his 2006 documentary Stephen Fry: The Secret Life of the Manic Depressive.[206][207] In an effort to ease the social stigma associated with bipolar disorder, the orchestra conductor Ronald Braunstein cofounded the ME/2 Orchestra with his wife Caroline Whiddon in 2011. Braunstein was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 1985 and his concerts with the ME/2 Orchestra were conceived in order to create a welcoming performance environment for his musical colleagues, while also raising public awareness about mental illness.[208][209]

Notable cases

Numerous authors have written about bipolar disorder and many successful people have openly discussed their experience with it.

Media portrayals

Several dramatic works have portrayed characters with traits suggestive of the diagnosis which have been the subject of discussion by psychiatrists and film experts alike.

In Mr. Jones (1993), (Richard Gere) swings from a manic episode into a depressive phase and back again, spending time in a psychiatric hospital and displaying many of the features of the syndrome.[215] In The Mosquito Coast (1986), Allie Fox (Harrison Ford) displays some features including recklessness, grandiosity, increased goal-directed activity and mood lability, as well as some paranoia.[216] Psychiatrists have suggested that Willy Loman, the main character in Arthur Miller's classic play Death of a Salesman, has bipolar disorder.[217]

The 2009 drama

Creativity

A link between mental illness and professional success or creativity has been suggested, including in accounts by Socrates, Seneca the Younger, and Cesare Lombroso. Despite prominence in popular culture, the link between creativity and bipolar has not been rigorously studied. This area of study also is likely affected by confirmation bias. Some evidence suggests that some heritable component of bipolar disorder overlaps with heritable components of creativity. Probands of people with bipolar disorder are more likely to be professionally successful, as well as to demonstrate temperamental traits similar to bipolar disorder. Furthermore, while studies of the frequency of bipolar disorder in creative population samples have been conflicting, full-blown bipolar disorder in creative samples is rare.[224]

Research

Research directions for bipolar disorder in children include optimizing treatments, increasing the knowledge of the genetic and neurobiological basis of the pediatric disorder and improving diagnostic criteria.[121] Some treatment research suggests that psychosocial interventions that involve the family, psychoeducation, and skills building (through therapies such as CBT, DBT, and IPSRT) can benefit in addition to pharmacotherapy.[155]

See also

- List of people with bipolar disorder

- Outline of bipolar disorder

- Bipolar I disorder

- Bipolar II disorder

- Bipolar NOS

- Cyclothymia

- Bipolar disorders research

- Borderline personality disorder

- Emotional dysregulation

- Mood (psychology)

- Mood swing

- International Society for Bipolar Disorders

Explanatory notes

Citations

- PMID 30745704.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-517668-1.

- ISBN 978-0-19-933234-2.

- ^ S2CID 22156246.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ^ PMID 24574956.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-19-068142-5.

- ^ PMID 28888714.

- ^ PMID 22459786.

- ^ NIMH (April 2016). "Bipolar Disorder". National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on July 27, 2016. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ^ S2CID 205976059.

- PMID 26979387.

Currently, medication remains the key to successful practice for most patients in the long term. ... At present the preferred strategy is for continuous rather than intermittent treatment with oral medicines to prevent new mood episodes.

- S2CID 198997808.

- ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ^ S2CID 263801832.

- S2CID 45781872.

- ^ S2CID 220309576.

- PMID 30887632.

- ^ S2CID 46097223.

- PMID 3394882.

- ^ Goodwin & Jamison 2007, p. 1945.

- ^ PMID 21320248.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-264-26850-4.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link - ^ a b Akiskal H (2017). "13.4 Mood Disorders: Clinical Features". In Sadock B, Sadock V, Ruiz P (eds.). Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry (10th ed.). New York: Wolters Kluwer.[ISBN missing]

- ^ PMID 20492846.

- ^ PMID 19358880.

- ^ PMID 21145595.

- ^ PMID 23005586.

- S2CID 144883133.

- PMID 21482326.

- PMID 15762854.

- PMID 20488276.

- PMID 22926687.

- ^ PMID 23457180.

- ^ PMID 24236353.

- S2CID 1880847.

- ^ "Bipolar Disorder: NIH Publication No. 95-3679". U.S. National Institutes of Health. September 1995. Archived from the original on April 29, 2008.

- ^ "Bipolar II Disorder Symptoms and Signs". Web M.D. Archived from the original on December 9, 2010. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ^ PMID 23901682.

- ^ PMID 11141528.

- PMID 18058287.

- ^ PMID 23223893.

- .

- PMID 32903205.

- ISBN 978-1-6654-3870-4.

- S2CID 264190691.

- PMID 11552957.

- S2CID 24177245.

- ^ S2CID 22983555.

- ^ PMID 17692389.

- PMID 15465978.

- PMID 12742871.

- ^ PMID 24683306.

- S2CID 33268.

- PMID 12802785.

- ^ S2CID 9502929.

- PMID 22573399.

- S2CID 9467242.

- PMID 18722519.

- S2CID 30065607.

- PMID 24718920.

- PMID 27126805.

- PMID 18332878.

- ^ PMID 23663953.

- PMID 23429820.

- PMID 38077849.

- PMID 18606036.

- PMID 25814263.

- ISBN 978-1-4377-0434-1

- S2CID 24812539.

- PMID 18762588.

- PMID 19721106.

- S2CID 2548825.

- ^ PMID 22631617.

- PMID 25482178.

- S2CID 214772559.

- PMID 21470688.

- PMID 25241675.

- PMID 21334286.

- PMID 24302944.

- ^ Brown & Basso 2004, p. 16.

- S2CID 24799032.

- PMID 23084802.

- S2CID 41155120.

- S2CID 19662149.

- S2CID 26907074.

- ISBN 978-3-642-15756-1.

- PMID 15597134.

- S2CID 6550069.

- PMID 16946919.

- ^ from the original on March 24, 2014.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-470-01795-1.

- ^ a b c "ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". World Health Organization. April 2019. p. 6A60, 6A61, 6A62. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- ^ S2CID 44868545.

- ^ S2CID 20010797.

- ^ Drs; Sartorius N, Henderson A, Strotzka H, Lipowski Z, Yu-cun S, You-xin X, et al. "The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines" (PDF). www.who.int World Health Organization. Microsoft Word. bluebook.doc. pp. 92, 97–99. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 17, 2004. Retrieved June 23, 2021 – via Microsoft Bing.

- ^ PMID 23219059.

- S2CID 32254230.

- PMID 15453104.

- S2CID 33811755.

- ISBN 978-1-107-60089-8.

- S2CID 1226279.

- ^ Korn ML. "Across the Bipolar Spectrum: From Practice to Research". Medscape. Archived from the original on December 14, 2003.

- PMID 31993793.

- ^ "Bipolar disorder". Harvard Health Publishing. November 2007. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

- OCLC 884617637.

- ^ PMID 24800202.

- PMID 25505679.

- S2CID 6629039.

- S2CID 13653149.

- PMID 18199234.

- S2CID 20001176.

- ^ PMID 26876316.

- PMID 23429819.

- ^ Sagman D, Tohen M (2009). "Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorder: The Complexity of Diagnosis and Treatment". Psychiatric Times. Archived from the original on April 28, 2009.

- PMID 11843782.

- ^ S2CID 689321.

- .

- ^ PMID 17716034.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Diler RS, Birmaher B (2019). "Chapter E2 Bipolar Disorders in Children and Adolescents". JM Rey's IACAPAP e-Textbook of Child and Adolescent Mental Health (PDF). Geneva: International Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions. pp. 1–37. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- PMID 25178749.

- PMID 20975827.

- PMID 28188565.

- ^ PMID 27601905.

- PMID 20307944.

- PMID 18606036.

- PMID 29361850.

- S2CID 201829716.

- S2CID 34615961.

- PMID 17329468.

- PMID 32762382.

- PMID 32356562.

- S2CID 201161580.

- PMID 17444074.

- PMID 16170918.

- ^ PMID 34623633.

- PMID 24167688.

- PMID 31152444.

- PMID 23814104.

- PMID 12535506.

- S2CID 105594.

- PMID 19555719.

- PMID 19118318.

- PMID 34523118.

- PMID 16437453.

- PMID 19160237.

- PMID 16856043.

- S2CID 43749362.

- ^ "Benzodiazepines for Bipolar Disorder". WebMD.com. Archived from the original on February 25, 2013. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- S2CID 252983016.

- PMID 34819636.

- PMID 34577534.

- ^ PMID 23927375.

- PMID 16432528.

- PMID 26467409.

- PMID 31802122.

- ^ PMID 32687629.

- PMID 25955325.

- ^ PMID 18425912.

- ^ PMID 28961441.

- ^ PMID 27121423.

- ^ PMID 25610528.

- ^ PMID 26628905.

- ^ PMID 26646576.

- PMID 26057335.

- S2CID 24013921.

- PMID 27685435.

- S2CID 22653449.

- PMID 26719696.

- PMID 15642648.

- ^ S2CID 207065294.

- S2CID 30881311.

- PMID 12738039.

- PMID 16125292.

- ^ McIntyre RS, Soczynska JK, Konarski J (October 2006). "Bipolar Disorder: Defining Remission and Selecting Treatment". Psychiatric Times. 23 (11): 46. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- PMID 23123569.

- S2CID 3763712.

- PMID 12507745.

- PMID 17485606.

- ^ Phelps J (2006). "Bipolar Disorder: Particle or Wave? DSM Categories or Spectrum Dimensions?". Psychiatric Times. Archived from the original on December 4, 2007.

- PMID 22983943.

- PMID 21131055.

- ^ Ayuso-Mateos JL. "Global burden of bipolar disorder in the year 2000" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-306-47268-8.

- PMID 30496104.

- ^ Borch-Jacobsen M (October 2010). "Which came first, the condition or the drug?". London Review of Books. 32 (19): 31–33. Archived from the original on March 13, 2015.

at the beginning of the 19th century with Esquirol's 'affective monomanias' (notably 'lypemania', the first elaboration of what was to become our modern depression)

- PMID 15506718.

- ^ Millon 1996, p. 290.

- PMC 5166213.

- ^ Goodwin & Jamison 2007, Chapter 1.

- PMID 11869749.

- ^ Bipolar Depression: Molecular Neurobiology, Clinical Diagnosis and Pharmacotherapy Archived May 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Carlos A. Zarate Jr., Husseini K. Manji, Springer Science & Business Media, April 16, 2009

- .

- ^ David L. Dunner interviewed by Thomas A. Ban Archived May 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine for the ANCP, Waikoloa, Hawaii, December 13, 2001

- ^ "More Than a Girl Singer". cancertodaymag.org. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- S2CID 5450333.

- ^ McCrone P, Dhanasiri S, Patel A, Knapp M, Lawton-Smith S. "PAYING THE PRICE The cost of mental health care in England to 2026" (PDF). kingsfund.org. The King's Fund. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- S2CID 25742003.

- PMID 25533912.

- PMID 17391357.

- ^ Stephens S (January 1, 2015). "Our Leading Lady, Carrie Fisher". bpHope.com. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ Howard J (December 27, 2016). "Carrie Fisher was a champion for mental health, too". CNN. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c Wiler S. "Carrie Fisher was a mental health hero. Her advocacy was as important as her acting". USA Today.

- ^ "The Secret Life of the Manic Depressive". BBC. 2006. Archived from the original on November 18, 2006. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ^ Barr S (March 26, 2018). "Stephen Fry discusses mental health and battle with bipolar disorder: 'I'm not going to kid myself that it's cured'". The Independent. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ Gram D (December 27, 2013). "For this orchestra, playing music is therapeutic". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 14, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ Strasser F, Botti D (January 7, 2013). "Conductor with bipolar disorder on music and mental illness". BBC News.

- ^ Jamison 1995.

- ISBN 978-1-4000-7717-5.

- ^ Michele R. Berman, Mark S. Boguski (July 15, 2020). "Understanding Kanye West's Bipolar Disorder". Archived from the original on June 7, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- ^ Naftulin J (August 7, 2020). "Selena Gomez opened up about the challenges of being in lockdown after her bipolar diagnosis". Insider. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Newall S (August 5, 2020). "Bipolar disorder: why we need to keep talking about it after the headlines fade". Harper's Bazaar. Retrieved January 14, 2022.

- ^ Robinson 2003, pp. 78–81.

- ^ Robinson 2003, pp. 84–85.

- ^ McKinley J (February 28, 1999). "Get That Man Some Prozac; If the Dramatic Tension Is All in His Head". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Child and Adolescent Bipolar Foundation special 90210 website". CABF. 2009. Archived from the original on August 3, 2012. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- ^ "EastEnders' Stacey faces bipolar disorder". BBC Press Office. May 14, 2009. Archived from the original on May 18, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ^ Tinniswood R (May 14, 2003). "The Brookie boys who shone at soap awards show". Liverpool Echo. Mirror Group Newspapers. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- Pilot". Homeland. Season 1. Episode 1. October 2, 2011. Showtime.

- ^ "Catherine Black by Kelly Reilly". American Broadcasting Company. Archived from the original on May 23, 2014. Retrieved May 22, 2014.

- ^ "How a white rapper's sidekick became a breakout sitcom star — and TV's unlikeliest role model". Los Angeles Times. April 15, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-470-66127-7.

Cited texts

- Brown MR, Basso MR (2004). Focus on Bipolar Disorder Research. ISBN 978-1-59454-059-2.

- Goodwin FK, Jamison KR (2007). Manic–depressive illness: bipolar disorders and recurrent depression (2nd. ed.). Oxford University Press. OCLC 70929267. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- Jamison KR (1995). An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-330-34651-1.

- Millon T (1996). Disorders of Personality: DSM-IV-TM and Beyond. New York: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-01186-6.

- Robinson DJ (2003). Reel Psychiatry: Movie Portrayals of Psychiatric Conditions. Port Huron, Michigan: Rapid Psychler Press. ISBN 978-1-894328-07-4.

Further reading

- Goldstein BI, Birmaher B, Carlson GA, DelBello MP, Findling RL, Fristad M, et al. (November 2017). "The International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force report on pediatric bipolar disorder: Knowledge to date and directions for future research". Bipolar Disorders. 19 (7): 524–543. PMID 28944987.