Bird's invasion of Kentucky

| Bird's invasion of Kentucky | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

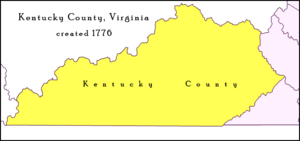

An illustration of Kentucky County, Virginia | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Shawnee |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Blue Jacket |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

150 regulars and militia 1,000 Indians | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 killed 1 wounded |

20 killed 450–350 captured | ||||||

Bird's invasion of Kentucky was one phase of an extensive planned series of operations planned by the British in 1780 during the American Revolutionary War, whereby the entire West, from Quebec to the Gulf of Mexico, was to be swept clear of both Spanish and American forces. While Bird's campaign met with limited success, raiding two fortified settlements, it failed in its primary objective. Other British operations that were part of the plan also failed.

Background

British authorities, during the spring of 1780, prepared to carry out a comprehensive plan for the recapture of the

No part of the plan proved successful. Campbell was preoccupied with the threat posed by

Invasion

From

Working its way without opposition along the Licking River, the vanguard of Bird's force reached Ruddle's Station, surrounding it on the night of June 21. Bird himself arrived the next day with the main body of his force, and cannon fire quickly breached the wooden walls of the station. Isaac Ruddle insisted on having the people under his protection treated as British captives, under the protection of the small British contingent. The Indians ignored this, and rushed into the fort to plunder and pillage. According to Bird "they rushed in, tore the poor children from their mothers' breasts, killed and wounded many."[2] After the Indians had divided the prisoners and loot to their satisfaction, they wanted to continue on to the next station. Bird successfully got them to agree that prisoners taken in the future would be turned over to them at British discretion.

Martin's Station, not far from Ruddle's was similarly surprised, and surrendered. The settlers at Martin's Station could hear the gunfire at Ruddell's Fort and were not surprised when the British appeared. They stayed with the walls of the station as their best protection, though they were compelled to surrender.[3] The Indians honored the bargain with Bird, and the prisoners were given over to the British soldiers. A war party of approximately sixty men split off from the larger campaign in order to attack Grant's Station (approximately 5 miles northeast of Bryan's). Although forty men were dispatched from Bryan's Station to provide relief, Grant's was burned, and two men and a woman were killed.[4]

While the Indians next wanted to attack Lexington, the largest settlement in the area, Bird ordered the expedition to end, citing depletion of provisions and reduced waterflow on the Licking River for the transport of the field cannons.

The expedition then retraced its steps. After crossing the Ohio, Indians who lived in the area (Delaware, Shawnee, and Miami) began leaving the expedition, taking their booty and prisoners with them. When Bird reached Fort Detroit on August 4, the force still held 300 prisoners taken from the two stations, including many slaves who were separated from their owners and kept as spoils of war by the raid's commanders.[5]

Aftermath

The fear Bird's campaign instilled led many settlers to abandon their lands and flee to the east. Clark, who wanted instead to recruit settlers for campaigns against the Indian settlements north of the Ohio that were home to some of the expedition's participants, closed the only road out of Kentucky to the east in order to gain additional recruits and weapons.

See also

- List of battles fought in Kentucky

- American Revolutionary War § Stalemate in the North. Places ' Siege of Fort Vincennes ' in overall sequence and strategic context.

References

- ^ Mahan, Russell, "The Kentucky Kidnappings and Death March: The Revolutionary War at Ruddell's Fort and Martin's Station," West Haven Utah: Historical Enterprises, 2020, pp. 37–47.

- ^ Banta, p. 157

- ^ Mahan, Russell, "The Kentucky Kidnappings and Death March: The Revolutionary War at Ruddell's Fort and Martin's Station," West Haven Utah: Historical Enterprises, 2020, pp. 69–78.

- ^ “Grant's Fort,” The Kentucky Encyclopedia (ed. John E. Kleber; Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1992), 383.

- ^ Banta, p. 158

Sources

- Adams, James Truslow. Dictionary of American History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1940

- Harrison, Lowell. A new history of Kentucky

- Banta, R. E. The Ohio

- Quaife, Milo M. (January 1927). "When Detroit Invaded Kentucky". Filson Club History Quarterly. 1 (2). Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- Mahan, Russell, "The Kentucky Kidnappings and Death March: The Revolutionary War at Ruddell's Fort and Martin's Station," West Haven Utah: Historical Enterprises, 2020.

External links

- "Ruddles & Martins Station Historical Association",

- J. Winston Coleman Jr., "The British Invasion of Kentucky," 1951.

- "The King's, or 8th Regiment – Detroit Garrison" Archived May 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, reenactment group