Biscay

Biscay

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Historical Territory of Biscay1 | ||

|

Juntas Generales de Vizcaya 51 | | |

| Website | Diputación Foral de Vizcaya | |

Biscay (/ˈbɪskeɪ, ˈbɪski/ BISK-ay, BISK-ee;[1][2] Basque: Bizkaia [bis̻kai.a]; Spanish: Vizcaya [biθˈkaʝa]) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country, heir of the ancient Lordship of Biscay, lying on the south shore of the eponymous bay. The capital and largest city is Bilbao.

Biscay is one of the most renowned and prosperous provinces of

Etymology

It is accepted in linguistics (Koldo Mitxelena, etc.) that Bizkaia is a cognate of bizkar (cf. Biscarrosse in Aquitaine), with both place-name variants well attested in the whole Basque Country and out[3] meaning 'low ridge' or 'prominence' (Iheldo bizchaya attested in 1141 for the Monte Igueldo in San Sebastián).[4]

Names

Bizkaia

Bizkaia is the official name, and it is used on official documents. It is also the name most used by the media in Spanish in the

Bizkaia is the only official name in Spanish or Basque approved for the historical territory by the

Vizcaya

Vizcaya is the name in the

History

Biscay has been inhabited since the Middle

Biscay was identified in records of the Middle Ages, as a dependency of the Kingdom of Pamplona (11th century) that became autonomous and finally a part of the Crown of Castile. The first mention of the name Biscay was recorded in a donation act to the monastery of Bickaga, located on the ria of Mundaka. According to Anton Erkoreka,[5] the Vikings had a commercial base there from which they were expelled by 825. The ria of Mundaka is the easiest route to the river Ebro and at the end of it, the Mediterranean Sea and trade.

In the

Paleolithic

Middle Paleolithic

The first evidence of human dwellings (Neanderthal people) in Biscay happens in this period of prehistory. Mousterian artifacts have been found in three sites in Biscay: Benta Laperra (Karrantza), Kurtzia (Getxo) and Murua (Durangoaldea).

Late Paleolithic

- Chatelperronian culture (normally associated with Neanderthals as well) can be found in Santimamiñecave (Kortezubi).

The most important settlements by modern humans (

- Aurignacian culture: Benta Laperra, Kurztia, and Lumentxa (Lekeitio)

- Gravettian culture: Santimamiñe, Bolinkoba (Durangoaldea) and Atxurra (Markina)

- Solutrean culture: Santimamiñe and Bolinkoba

- Magdalenian culture: Santimamiñe and Lumentxa

Epi-paleolithic

This period (also called Mesolithic sometimes) is dominated in Biscay by the Azilian culture. Tools become smaller and more refined and, while hunting remains, fishing and seafood gathering become more important; there is evidence of consumption of wild fruits as well. Santimamiñe is one of the most important sites of this period. Others are Arenaza, Atxeta (not far from Santimamiñe), Lumentxa and nearby Urtiaga and Santa Catalina, together with Bolinkoba and neighbour Silibranka.

Neolithic

While the first evidences of Neolithic contact in the Basque Country can be dated to the 4th millennium BCE, it was not until the beginning of the 3rd that the area accepted, gradually and without radical changes, the advances of agricultural cultivation and domestication of sheep. Biscay was not particularly affected by this change and only three sites can be mentioned for this period: Arenaza, Santimamiñe and Kobeaga (Ea) and the advances adopted seem limited initially to sheep, domestic goats and very scarce pottery.

Together with Neolithic technologies, Megalithism also arrives. It will be the most common form of burial (simple dolmen) until c. 1500 BCE.

Chalcolithic and Bronze Age

While open-air settlement started to become common as the population grew, they still used caves and natural shelters in Biscay in the

Pottery types shows great continuity (not decorated) until the

The sites of this period now cover all the territory of Biscay, many being open air settlements, but the most important caves of the Paleolithic are still in use as well.

Iron Age

Few sites have been identified for this period. Caves are abandoned for the most part but they still reveal some remains. The main caves of prehistory (Arenaza, Santimamiñe, Lumentxa) were still inhabited.

Roman period

Roman geographers identified two tribes in the territory now known as Biscay: the

There is no indication to resistance to Roman occupation in all the Basque area (excepting

In the late Roman period, together with the rest of the Basque Country, Biscay seems to have revolted against Roman domination and the growing society organized by feudalism.

Middle Ages

In the Early

In 905, Leonese chronicles define for the first time the

In the conflicts that the newly sovereign

The title to the lordship was inherited by Iñigo López's descendants until, by inheritance, in 1370 it passed to John I of Castile. It became one of the titles of the king of Castile. Since then it remained connected to the crown, first to that of Castile and then, from Charles I, to that of Spain, as ruler of the Crown of Castile. It was conditioned on the lord swearing to defend and maintain the fuero (Biscayan laws, derived from Navarrese and Basque customary rights), which affirmed that the possessors of the sovereignty of the lordship were the Biscayans and that, at least in theory, they could refute the lord.

The lords and later the kings, came to swear the Statutes to the oak of Gernika, where the assembly of the Lordship sits.

Modern age

In the

In 1628, the separate territory of

The coastal towns had a sizable fleet of their own, mostly dedicated to fishing and trade. Along with other Basque towns of Gipuzkoa and Labourd, they were largely responsible for the partial extinction of North Atlantic right whales in the Bay of Biscay and of the first unstable settlement by Europeans in Newfoundland. They signed separate treaties with other powers, particularly England.[citation needed]

After the

Many of the towns though, notably Bilbao, were aligned with the Liberal government of

In the 1850s extensive prime quality iron resources were discovered in Biscay. This brought much foreign investment mainly from England and France. Development of these resources led to greater industrialization, which made Biscay one of Spain's richest provinces. Together with the

20th century

During the Second Spanish Republic, the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) governed the province. When the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, Biscay supported the Republican side against Francisco Franco's army and ideology. Soon after, the Republic acknowledged a statute of autonomy for the Basque Country. Due to fascist control of large parts of it, the first short-lived Basque Autonomous Community had power only over Biscay and a few nearby villages.

As the fascist army advanced westward from Navarre, defenses were planned and erected around Bilbao, called the Iron Belt. But the engineer in charge,

Under the dictatorship of Franco, Biscay and Gipuzkoa (exclusively) were declared "traitor provinces" because of their opposition and stripped of any sort of self-rule. Only after Franco's death in 1975 was democracy restored in Spain. The 1978 constitution accepted the particular Basque laws (fueros) and in 1979 the Statute of Guernica was approved whereupon Biscay, Araba and Gipuzkoa formed the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country with its own parliament. During this recent democratic period, Basque Nationalist Party candidates have consistently won elections in Biscay. Recently the foral law was amended to extend it to the towns and the city of Urduina, which had previously always used the general Spanish Civil law.

Geography

Biscay is bordered by the community of

Climate

The climate is oceanic, with high precipitation all year round and moderate temperatures, which allow the lush vegetation to grow. Temperatures are more extreme in the higher lands of inner Biscay, where snow is more common during winter. The average high temperatures in main city Bilbao is between 13 °C (55 °F) in January and 26 °C (79 °F) in August.[7]

Features

The main geographical features of the province are:

- The southern high , 1331 m).

- The middle section which is occupied by the main river's valleys: Kadagua. Kadagua runs west to east from Ordunte, Nervion south to north from Orduña and Ibaizabal east to west from Urkiola. The Arratia river runs northwards from Gorbea and joins Ibaizabal. Each valley is separated by mountains like Ganekogorta (998 m). Other mountains, like Oiz, separate the main valleys from the northern valleys. The northern rivers are Artibai, Lea, Oka and Butron.

- The coast: the main features are the Urdaibai). The coast is usually high, with cliffs and small inlets and coves.

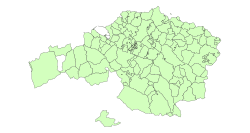

Administrative divisions

Historical

Historically, Biscay was divided into merindades (called eskualdeak in Basque), which were two, the Constituent ones and the ones incorporated later.

The constituent ones were (the number indicates their position on the map):

Incorporated later:

- Durango

- Enkarterri

- Orozko

- Orduña

- Some other independent cities and towns.

Modern

Currently, Biscay is divided into seven comarcas or regions, each one with its own capital city, subdivisions and municipalities.

These are:

- Greater Bilbao, usually divided into subregions:

- Mungialdea

- Enkarterri

- Busturialdea

- Durangaldea

- Lea-Artibai

- Arratia-Nerbioi

Demographics

According to the 2010

A 2021 survey found that 30.6% of the population spoke the Basque language.[8]

| Demographic evolution of Biscay and percentage of the national total[9][10] | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1857 | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | |||||||||||||

| Population | 160,579 | 311,361 | 349,923 | 409,550 | 485,205 | 511,135 | 569,188 | ||||||||||||

| Percentage | 1.04% | 1.67% | 1.75% | 1.91% | 2.05% | 1.96% | 2.02% | ||||||||||||

| 1960 | 1970 | 1981 | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | |||||||||||||

| Population | 754,383 | 1,043,310 | 1,181,401 | 1,156,245 | 1,140,026 | 1,132,616 | 1,139,863 | ||||||||||||

| Percentage | 2.47% | 3.07% | 3.13% | 2.93% | 2.87% | 2.75% | 2.55% | ||||||||||||

| Most populated municipalities (2021) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | Municipality | Inhabitants | |||||

| 1st | Bilbao | 346,405 | |||||

| 2nd | Barakaldo | 100,907 | |||||

| 3rd | Getxo | 77,139 | |||||

| 4th | Santurtzi | 46,085 | |||||

| 5th | Portugalete | 45,285 | |||||

| 6th | Basauri | 40,535 | |||||

| 7th | Leioa | 32,188 | |||||

| 8th | Durango |

29,935 | |||||

| 9th | Galdakao | 29,404 | |||||

| 10th | Sestao | 27,342 | |||||

| 11th | Erandio | 24,489 | |||||

| 12th | Amorebieta-Etxano | 19,576 | |||||

| 13th | Mungia | 17,701 | |||||

| 14th | Gernika-Lumo |

17,093 | |||||

| 15th | Bermeo | 16,784 | |||||

Government and foral institutions

The government and foral institutions of Biscay, as a historical territory of the

Juntas Generales

The

After the 2015 elections, the configuration of the Juntas is the following:[11]

| Elecciones a las Juntas Generales 2015 | ||||

| Party | Apoderados | |||

| Basque Nationalist Party | 23 | |||

Bildu

|

11 | |||

| Socialist Party of the Basque Country–Basque Country Left | 7 | |||

| Podemos | 6 | |||

| People's Party | 4 | |||

Foral Diputation

The Foral Diputation has an executive function and regulatory authority in Biscay. The Foral Diputation is configured by a General Deputy, who currently is Unai Rementeria[12] (PNV) and who is chosen by the Juntas Generales and by the rest of deputies.

Transportation

Roads

Biscay is connected to the rest of provinces by two main highways, the

As well, many secondary roads connect Bilbao with the different towns located in the province.

Air

Biscay's main and only airport is Bilbao Airport, which is the most important hub in northern Spain, and the number of passengers using the new terminal continues to rise. It is located in the municipalities of Loiu and Sondika.

Commuter rail

Biscay has different

Long distance railways

community.The

.Metro

Tourism

Biscay's capital city, Bilbao, is famous for the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and for its estuary.

Monuments and places of general interest

- Casa de Juntas (House of the Juntas) and the Gernika.

- Casa de Juntas (House of the Juntas) of Avellanada, in the Enkarterri region.

- Pozalagua Cave in Karrantza near Balmaseda

- Vizcaya Bridge, linking the towns of Portugalete and Getxo

- Santimamiñe and the Oma forest

- Euskalduna Conference Centre and Concert Hall in Bilbao.

- Gaztelugatxe

- Urdaibaibiosphere reserve

- Urkiola Natural Park

-

Guggenheim Museum and the Estuary of Bilbao

-

Gaztelugatxe islet

-

Casa de Juntas of Avellanada

-

Urdaibai

See also

Notes and references

- ^ "Biscay". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ "Vizcaya". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ISBN 84-7148-008-5.

- ^ "Toponimia: Bizkaia", Noticias de Gipuzkoa, pp. "Ortzadar", 08, 2010-05-08, retrieved 2010-05-08

- ^ Anton Erkoreka, Los Vikingos en Euskal Herria, Bilbao, 1995

- ^ "Euskalherria.com - GARA - Paperezkoa:20060616 - los textos hallados en Iruña-Veleia están escritos "inequívocamente" en euskara". Archived from the original on 2007-01-06. Retrieved 2006-10-06.

- ^ "Standard climate values for Bilbao". Aemet.es. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ "The Basque Language Gains Speakers, but No Surge in Usage – Basque Tribune".

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spain).

- ^ euskadi.net Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "M24: Hauteskundeak" (in Basque). naiz.info. 24 May 2015.

- ^ "Ahaldun Nagusia - Bizkaia.eus". web.bizkaia.eus (in Basque). Retrieved 2018-08-21.

External links

- Official website

- Señores de Vizcaya: list of all claimed Lords of Biscay and interesting historical maps.