Bisphosphonate

Bisphosphonates are a class of drugs that prevent the loss of bone density, used to treat osteoporosis and similar diseases. They are the most commonly prescribed drugs used to treat osteoporosis.[1] They are called bisphosphonates because they have two phosphonate (PO(OH)

2) groups. They are thus also called diphosphonates (bis- or di- + phosphonate).

Evidence shows that they reduce the risk of fracture in post-menopausal women with osteoporosis.[2][3][4][5][6]

The uses of bisphosphonates include the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis,

Medical uses

Bisphosphonates are used to treat osteoporosis,

In osteoporosis and Paget's, the most popular first-line bisphosphonate drugs are

Post-menopausal osteoporosis

Bisphosphonates are recommended as a first line treatments for post-menopausal osteoporosis.[5][10][11][12]

Long-term treatment with bisphosphonates produces anti-fracture and bone mineral density effects that persist for 3–5 years after an initial 3–5 years of treatment.[2] The bisphosphonate alendronate reduces the risk of hip, vertebral, and wrist fractures by 35-39%; zoledronate reduces the risk of hip fractures by 38% and of vertebral fractures by 62%.[3][4] Risedronate has also been shown to reduce the risk of hip fractures.[5][6]

After five years of medications by mouth or three years of intravenous medication among those at low risk, bisphosphonate treatment can be stopped.[13] In those at higher risk ten years of medication by mouth or six years of intravenous treatment may be used.[13]

Cancer

Bisphosphonates reduce the risk of fracture and bone pain[14] in people with breast,[15] lung,[16] and other metastatic cancers as well as in people with multiple myeloma.[17] In breast cancer there is mixed evidence regarding whether bisphosphonates improve survival.[15][18][19][20] A 2017 Cochrane review found that for people with early breast cancer, bisphosphonate treatment may reduce the risk of the cancer spreading to the person's bone, however, for people who had advanced breast cancer bisphosphonate treatment did not appear to reduce the risk of the cancer spreading to the bone.[15] Side effects associated with bisphosphonate treatment for people with breast cancer are mild and rare.[15]

Bisphosphonates can also reduce mortality in those with multiple myeloma and prostate cancer.[20]

Other

Evidence suggests that the use of bisphosphonates would be useful in the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome, a neuro-immune problem with high MPQ scores, low treatment efficacy and symptoms which can include regional osteoporosis. In 2009 bisphosphonates were "among the only class of medications that has survived placebo-controlled studies showing statistically significant improvement (in CRPS) with therapy."[21]

Bisphosphonates have been used to reduce fracture rates in children with the disease osteogenesis imperfecta[22] and to treat otosclerosis[23] by minimizing bone loss.

Other bisphosphonates, including

Adverse effects

Common

Oral bisphosphonates can cause upset

Bisphosphonates, when administered intravenously for the treatment of cancer, have been associated with

A number of cases of severe bone, joint, or musculoskeletal pain have been reported, prompting labeling changes.[25]

Some studies have identified bisphosphonate use as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation (AF), though meta-analysis of them finds conflicting reports. As of 2008[update], the US Food and Drug Administration did not recommend any alteration in prescribing of bisphosphonates based on AF concerns.[26] More recent meta-analyses have found strong correlations between bisphosphonate use and development of AF, especially when administered intravenously,[27] but that a significantly increased risk of AF that required hospitalization did not have an attendant increased risk of stroke or cardiovascular mortality.[28]

Long-term risks

In large studies, women taking bisphosphonates for osteoporosis have had unusual fractures ("bisphosphonate fractures") in the

Three meta analyses have evaluated whether bisphosphonate use is associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer. Two studies concluded that there was no evidence of increased risk.[32][33][34]

Chemistry and classes

All bisphosphonate drugs share a common phosphorus-carbon-phosphorus "backbone":

The two PO

3 (

The long side-chain (R2 in the diagram) determines the chemical properties, the mode of action and the strength of bisphosphonate drugs. The short side-chain (R1), often called the 'hook', mainly influences chemical properties and pharmacokinetics.

See nitrogenous and non-nitrogenous sections in Mechanism of action below.

Pharmacokinetics

Of the bisphosphonate that is resorbed (from oral preparation) or infused (for

Mechanism of action

Bisphosphonates are structurally similar to pyrophosphate, but with a central carbon that can have up to two substituents (R1 and R2) instead of an oxygen atom. Because a bisphosphonate group mimics the structure of pyrophosphate, it can inhibit activation of enzymes that utilize pyrophosphate.

The specificity of bisphosphonate-based drugs comes from the two phosphonate groups (and possibly a hydroxyl at R1) that work together to coordinate calcium ions. Bisphosphonate molecules preferentially bind to calcium ions. The largest store of calcium in the human body is in bones, so bisphosphonates accumulate to a high concentration only in bones.

Bisphosphonates, when attached to bone tissue, are released by osteoclasts, the bone cells that break down bone tissue. Bisphosphonate molecules then attach to and enter osteoclasts where they disrupt intracellular enzymatic functions needed for bone resorption.[36]

There are two classes of bisphosphonate compounds: non-nitrogenous (no nitrogen in R2) and nitrogenous (R2 contains nitrogen). The two types of bisphosphonates work differently in inhibiting osteoclasts.

| Class | Name | R1 | R2 | Relative potency (vs Etidronate=1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Etidronate (Didronel) | OH | CH3 | 1 | |

Clodronate (Bonefos, Loron)

|

Cl | Cl | 10 | |

Tiludronate (Skelid)

|

H | p-Chlorophenylthio | 10 | |

Pamidronate (APD, Aredia)

|

OH | (CH2)2NH2 | 100 | |

Neridronate (Nerixia[a] )

|

OH | (CH2)5NH2 | 100 | |

Olpadronate

|

OH | (CH2)2N(CH3)2 | 500 | |

Alendronate (Fosamax)

|

OH | (CH2)3NH2 | 500 | |

Ibandronate (Boniva - US, Bonviva - Asia)

|

OH | (CH2)2N(CH3)(CH2)4CH3 | 1000 | |

Risedronate (Actonel)

|

OH | 3-Pyridylmethyl | 2000 | |

Zoledronate (Zometa, Aclasta)

|

OH | 1H-imidazol-1-ylmethyl | 10000 |

Non-nitrogenous

The non-nitrogenous bisphosphonates (diphosphonates) are metabolised in the cell to compounds that replace the terminal pyrophosphate moiety of ATP, forming a non-functional molecule that competes with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in the cellular energy metabolism. The osteoclast initiates apoptosis and dies, leading to an overall decrease in the breakdown of bone. This type of bisphosphonate has overall more negative effects than the nitrogen containing group, and is prescribed far less often.[37]

Nitrogenous

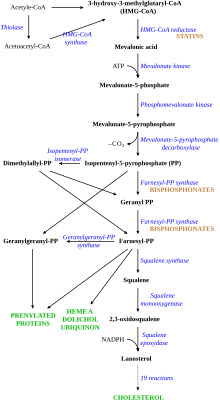

Nitrogenous bisphosphonates act on bone metabolism by binding and blocking the enzyme

Bisphosphonates that contain isoprene chains at the R1 or R2 position can impart specificity for inhibition of GGPS1.[39]

Disruption of the HMG CoA-reductase pathway at the level of FPPS prevents the formation of two metabolites (farnesol and geranylgeraniol) that are essential for connecting some small proteins to the cell membrane. This phenomenon is known as prenylation, and is important for proper sub-cellular protein trafficking (see "lipid-anchored protein" for the principles of this phenomenon).[40]

While inhibition of protein prenylation may affect many proteins found in an

proteins has been speculated to underlie the effects of bisphosphonates. These proteins can affect both osteoclastogenesis, cell survival, and cytoskeletal dynamics. In particular, the cytoskeleton is vital for maintaining the "ruffled border" that is required for contact between a resorbing osteoclast and a bone surface.History

Bisphosphonates were developed in the 19th century but were first investigated in the 1960s for use in disorders of bone metabolism. Their non-medical use was to soften water in irrigation systems used in orange groves. The initial rationale for their use in humans was their potential in preventing the dissolution of

Notes

References

- ^ National Osteoporosis Society. "Drug Treatment". U.K. National Osteoporosis Society. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ PMID 24120384.

- ^ S2CID 20163452.

- ^ PMID 24278999.

- ^ PMID 21224201.

- ^ PMID 23079689.

- PMID 19118304.

- ^ "Strontium ranelate: cardiovascular risk—restricted indication and new monitoring requirements Article date: March 2014". MHRA.

- PMID 27706804.

- S2CID 7980731.

- PMID 23944732.

- PMID 23810490.

- ^ PMID 26350171.

- PMID 23279447.

- ^ PMID 29082518.

- PMID 22956190.

- PMID 29253322.

- PMID 23990894.

- PMID 23452992.

- ^ PMID 26617219.

- PMID 18486850.

- S2CID 205834462.

- PMID 19205157.

- S2CID 53091343.

- PMID 15710802.

- Food and Drug Administration (United States). October 2008. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- PMID 24837258.

- PMID 23722644.

- ^ PMID 20335574.

- PMID 18354114.

- .

- S2CID 5271005.

- S2CID 12625687.

- PMID 23155320.

- ^ "Bisphosphonates". courses.washington.edu. Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- PMID 18325866.

- PMID 9286751.

- PMID 14623056.

- S2CID 27913789.

- S2CID 20316713.

- PMID 17409043.

- PMID 11879557.