Black-and-white colobus

| Black-and-white colobus[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

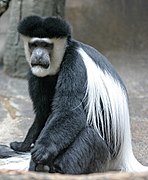

| Mantled guereza (Colobus guereza) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Cercopithecidae |

| Subfamily: | Colobinae |

| Tribe: | Colobini |

| Genus: | Colobus Illiger, 1811 |

| Type species | |

Simia polycomos

, 1780) | |

| Species | |

| |

Black-and-white colobuses (or colobi) are

Etymology

The word "colobus" comes from

Taxonomy

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angola colobus | C. angolensis P. L. Sclater, 1860 Six subspecies

|

Central Africa

|

Size: 49–68 cm (19–27 in) long, plus 70–83 cm (28–33 in) tail[5] Habitat: Forest[6] Diet: Leaves, as well as stems, bark, flowers, buds, shoots, fruits, and insects[5] |

VU

|

| Black colobus | C. satanas Waterhouse, 1838 Two subspecies

|

Western Africa

|

Size: 50–70 cm (20–28 in) long, plus 62–88 cm (24–35 in) tail[7] Habitat: Forest[8] Diet: Nuts and seeds, as well as unripe fruit and leaves[7] |

VU

|

| King colobus | C. polykomos (Zimmermann, 1780) |

Western Africa

|

Size: 45–72 cm (18–28 in) long, plus 52–100 cm (20–39 in) tail[9] Habitat: Forest and savanna[10] Diet: Leaves, as well as fruit and flowers[9] |

EN

|

| Mantled guereza | C. guereza Rüppell, 1835 Seven subspecies

|

Central Africa

|

Size: 45–72 cm (18–28 in) long, plus 52–100 cm (20–39 in) tail[11] Habitat: Forest[12] Diet: Leaves, as well as fruit, buds, and blossoms[11] |

LC

|

| Ursine colobus | C. vellerosus (I. Geoffroy, 1834) |

Western Africa

|

Size: 60–67 cm (24–26 in) long, plus 73–93 cm (29–37 in) tail[13] Habitat: Forest[14] Diet: Leaves and seeds, as well as fruit, insects, and clay[15] |

CR

|

Fossil species

Behaviour and ecology

Colobus habitats include primary and secondary forests, riverine forests, and wooded grasslands; they are found more in higher-density logged forests than in other primary forests. Their ruminant-like digestive systems have enabled them to occupy niches that are inaccessible to other primates: they are herbivorous, eating leaves, fruit, flowers, lichen, herbaceous vegetation and bark. Colobuses are important for seed dispersal through their sloppy eating habits, as well as through their digestive systems.

Leaf toughness influences colobus foraging efficiency. Tougher leaves correlate negatively with ingestion rate (g/min) as they are costly in terms of mastication, but positively with investment (chews/g).[16] Individuals spend approximately 150 minutes actively feeding each day.[16] In a montane habitat colobus are known to utilise lichen as a fallback food during periods of low food availability.[17]

Social patterns and morphology

Colobuses live in territorial groups that vary in both size (3-15 individuals) and structure.[2][18][19] It was originally believed that the structure of these groups consisted of one male and about 8 female members.[20] However, more recent observations have shown variation in structure and the number of males within groups, with one species forming multi-male, multifemale groups in a multilevel society, and in some populations supergroups form exceeding 500 individuals.[18][19] There appears to be a dominant male, whilst there is no clear dominance among female members.[2] Relationships among females are considered to be resident-egalitarian, as there is low competition and aggression between them within their own groups. Juveniles are treated as a lower-rank (in regards to authority) than subadults and likewise when comparing subadults to adults.[3] Colobuses do not display any type of seasonal breeding patterns.[21]

As suggested by their name, adult colobi have black fur with white features. White fur surrounds their facial region and a "U" shape of long white fur runs along the sides of their body. Newborn colobi are completely white with a pink face. Cases of allomothering are documented, which means members of the troop other than the infant's biological mother care for it. Possible explanations to this are, increasing inclusive fitness or maternal practice which will benefit future offspring.[22]

Social behaviours

Many members participate in a greeting ritual when they are reunited with familiar individuals, an act of reaffirming.

Conservation

They are prey for many forest predators, and are threatened by hunting for the bushmeat trade, logging, and habitat destruction.

Individuals are more vigilant (conspecific threat) in low canopy, they also spend less time scanning when they are around familiar group members as opposed to unfamiliar.[23] There are no clear difference in vigilance between male and females. However, there is a positive correlation between mean monthly vigilance and encounter rates.[23] Male vigilance generally increases during mating.[24]

References

- ^ OCLC 62265494.

- ^ S2CID 24835234.

- ^ S2CID 25163826.

- ^ PMID 9651650.

- ^ a b Thompson, Brandon (2002). "Colobus angolensis". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ .

- ^ a b Lane, Whitney (2011). "Colobus satanas". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ .

- ^ a b Landes, Devon (2000). "Colobus polykomos". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ .

- ^ a b Kim, Kenneth (2002). "Colobus guereza". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ .

- ^ Kingdon 2015, p. 114

- ^ .

- ^ Walker, Shannon (2009). "Colobus vellerosus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ PMID 27346431.

- S2CID 212731904.

- ^ S2CID 214808996.

- ^ PMID 31618212.

- ISSN 0005-7959.

- S2CID 31872244.

- S2CID 14120148.

- ^ S2CID 205329258.

- S2CID 53202789.

Sources

- Kingdon, Jonathan (2015). The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals (Second ed.). ISBN 978-1-4729-2531-2.