Black Army of Hungary

| Black Army | |

|---|---|

János Corvinus, son of King Matthias, into Vienna. In the Philostratus Chronicle, the apparent black colour of the flag used to be white (argent), but the argent paint oxidized. The reconstruction preserves the original colour. | |

| Mascot(s) | Raven |

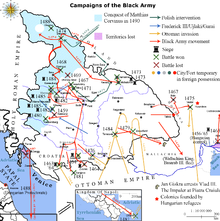

| Engagements | Holy Roman Empire, Bohemia, Poland, Serbia, Bosnia, Moldavia, Wallachia, Italy |

| Commanders | |

| King | Matthias Corvinus |

| Notable commanders | Pál Kinizsi, Balázs Magyar, Imre Zápolya, John Giskra, John Haugwitz, František Hag, Vuk Grgurević, Đorđe Branković |

The Black Army (Hungarian: Fekete sereg, pronounced [ˈfɛkɛtɛ ˈʃɛrɛɡ], Latin: Legio Nigra), also called the Black Legion/Regiment – were the military forces serving under the reign of King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary. The ancestor and core of this early standing mercenary army appeared in the era of his father John Hunyadi in the early 1440s. The idea of the professional standing mercenary army came from Matthias' juvenile readings about the life of Julius Caesar.[2]

Hungary's Black Army traditionally encompasses the years from 1458 to 1494.

Matthias recognized the importance and key role of early

In the beginning, the core of the army consisted of 6,000–8,000 mercenaries. and, from 1480, Hungarians.

The Black Army was not the only large standing mercenary army of Matthias Corvinus. The border castles of the north, west and east were guarded mostly by the retinues of the local nobility, financed by the nobles' own revenues; however the Ottoman frontier zone of southern Hungary had a large professional standing army which was paid by the king. Unlike the soldiers of the Black Army, these large mercenary garrisons were trained for castle defence. No other contemporary European realm would have been able to maintain two large parallel permanent forces for so long.[12]

The death of Matthias Corvinus meant the end of the Black Army. The noble estate of the parliament succeeded in reducing the tax burden by 70–80 percent, at the expense of the country's ability to defend itself,

Etymology

Several theories exist about the army's name. The first recorded accounts using "black" description appear in written memoranda immediately after Corvinus' death, when the rest of the army was pillaging Hungarian, and later Austrian, villages when they were receiving no pay. One idea is that they adopted the adjective from a captain, "Black" John Haugwitz, whose nickname already earned him enough recognition to be identified with the army as a whole.[7]

Reforms of the draft of traditional feudal and levy armies

In the first years of Matthias' rule, the structure of enlisting troops was built on the legacy of his ancestor

In case of emergency, a last chance existed for the actual king in power to mobilize the population suddenly. Every noble, no matter his social class, had to participate in person with his weaponry and all of his personal guards made available. These were the estate armies.

In the laws of 1459 of Szeged, he restored the basis of 20 serfs to induct an archer (this time it was based on the number of persons). The barons' militia portalis no longer counted in the local noble's banner but into the army of the country (led by a captain appointed by the king) and could have been sent abroad as well. He also increased the insurrectio's time of service from 15 days to three months.[17]

From mercenaries to regularly paid soldiers

Though these efforts were sound, the way they were carried out was not in any way supervised. In 1458, Matthias borrowed as many as 500 heavy cavalry from the Bohemian king,

Funding

After Matthias's income increased periodically, simultaneously, the number of mercenaries increased as well. Historical records vary when it comes to numbers, mainly because it changed from battle to battle and most soldiers were only employed for the duration of combat or a longer conflict.[citation needed] Reckoning the nobility's banners, the mercenaries, the soldiers of conquered Moravia and Silesia, and the troops of allied Moldavia and Wallachia, the King could have gathered an army of 90,000 men.[citation needed] The nobility's participation in the battlefield was ignored by the time their support could have been redeemed in gold later on. The cities were also relieved of paying war levies if they supplied the craftsmanship and weapon production to equip the military.[citation needed]

King Matthias increased the serfs' taxes; he switched the basis of taxing from the portae[clarification needed] to the households, and occasionally, they collected the royal dues twice a year during wartime. Counting the vassals' tribute, the western contributions, the local nobility's war payment, the tithes, and the urban taxes, Matthias's annual income reached 650,000 florins; for comparison, the Ottoman Empire had 1,800,000 per year.[19] In contrast to popular belief, historians have speculated for decades that the actual sum altogether could circle around 800,000 florins in a good year at the peak of Matthias's reign, but never surpassed the financial threshold of one million florins, a previously commonly accepted number.[20] In 1467, Matthias Corvinus reformed the coin system for easier accumulation of taxes and manageable disbursements and introduced an improved dinar, which had a finer silver content (500‰) and weighed half a gram. He also re-established its ratio, where one florin of gold equaled 100 dinars of silver, which was so stable that it remained in place until the mid-16th century.[21]

The army was divided into three parts: the cavalry, paid three florins per horse; the

Improving the river fleet

The river fleet (

Branches, tactics, equipment

Tactics

... we regard the armored heavy infantry as a wall, who never give up their place, even if they are slaughtered to the last one of them, on the very spot they are standing. Light soldiers perform breakouts depending on the occasion, and when they are already tired or sense severe danger, they return behind the armoured soldiers, organizing their lines and collecting power, and stay there until, on occasion, they may break forth again. In the end, all of the infantry and shooters are surrounded by armoured and shielded soldiers, just as those were standing behind a rampart. Since, the greater pavieses, put next to each other in a circle, show the picture of a fortress, and are similar to a wall, in the protection whereof the infantry and all the ones standing in the middle, fight like from behind tower-walls or rampart, and they occasionally break out of there.

— Matthias Corvinus, in a letter to his father-in-law King Ferdinand I of Naples in the 1480s.[27]

Heavy cavalry

At the height of the century, heavy cavalry was already at its peak, although it showed signs of declining tendencies. The striking power and the ability to charge without backup made it capable of forcing a decisive outcome in most battles. Although it was rarely deployed on their own, if it was, it would take square formations. Such turning points occurred at the Battle of Breadfield (1479). Usually, it made up one-sixth of the army and, with mercenary knights, was in the majority. Its armament was well prepared and of high quality except for the noble banners. This stands for proprietary arms, not the ones provided by the king.

Weaponry

- Lances: the lance was the principal assault weapon of the tilting heavy cavalry. They were up to four metres long, ranging from the classical lance type with a lengthened spearhead (often decorated with animal tails, flags or other ornaments) to the short conical spearheaded, one designed for piercing heavy armour. A buckler-like vamplate protected the hand and arm. Its stability was increased with a fastening hook (lance-arret) on the side of the horseman's cuirass.

- bastard swords also came into use. As a companion weapon, daggers of saw-toothed and flame-form type were applied (both with ring-guard) and a misericordia.

- Apart from these, they carried auxiliary weapons, such as Gothic maces, flanged maces, axes, crossbows (balistrero ad cavallo) and short shields similar in design to the pavise (petit pavois) for defense.[30]

Light cavalry

The traditional hussars were introduced by Matthias; henceforth, the light cavalry is called huszár, a name derived from the word húsz ("twenty" in English), which refers to the drafting scheme where for every twenty serfs a noble owned, he had to equip a mounted soldier. After the Diet of Temesvár (Timişoara) of 1397, the light cavalry was institutionalized as an army division. According to Antonio Bonfini, this lightly armed cavalry (expeditissimus equitatus) was not allowed to be part of the regular army when the order of the battle was formed, but was placed outside it in quite separate groups and used to destroy, burn, kill and instil fear in the civilian population, while they rode ahead of the regular army.[31] They assembled from the militia portalis, a significant number of them insurrectios, the Moldavians and Transylvanians with the first having serfs with lesser accoutrement and the latter generally regarded as good horse archers. They were divided into groups of 25 (turma) led by a captain (capitaneus gentium levis armature). Their field of operation was scouting, securing, prowling, cutting enemy supply lines, and disarraying them in battle. They also served as an additional maneuverable flank (for swooping advance attacks) to strong centers of heavy cavalry. The medieval Hungarian written sources spoke disparagingly and contemptuously of the light cavalry and the hussars in general, and during battles the texts praised only the virtues, endurance, courage, training and achievements of the knights. During the Middle Ages, Hungarian soldiers of noble origin served exclusively as heavy armoured cavalry.[32]

Weaponry

Helmet, mail shirt, sabre, targe, spear and, in some cases, axes (including throwing axes).

- Sabres (szablya): one type followed the tradition of southern European longswords (S-shaped crossguard), while gradually transforming into an Eastern-style blended (Turkish) sabre. The other type was the so-called huszarszablya (hussarsabre), a 40 mm wide multi-layered sabre stuck with 3–6 rivets.

- Bows: the traditional Magyar composite bow and, due to heavy Eastern influence, the more powerful Turkish-Tatar bow came into play.

- Axes: throwing axes could also have had some role in light cavalry tactics. It was made from one piece of metal, with a short engraved haft. If the arc of the blade is almost flat or slightly curved, it is called the "Hungarian-type axe". A subsidiary to the aforementioned beaked pickaxe was also favoured: it had a beak-like, protruding edge, resulting in a stronger piercing effect.[30]

Infantry

Infantry was less important but formed a stable basis in the integrity of an army. They were organized from mixed ethnicities and were composed of heavy infantry, shielded soldiers, light infantry and fusiliers. Their characteristics include the combination of plate and mail armour and the use of the pavises (these painted willow-wood large shields were often ornamented and covered with leather and linen). The latter served multiple purposes: to hold off enemy attacks, to cover ranged infantry shooting from behind (fusiliers engage first, the archers fire constantly), and moveable hussite-style

In 1481, the Black Army's infantry was described as follows:

The third form of the army is the infantry, which divides into various orders: the common infantry, the armoured infantry, and the shield bearers. ... The armored infantry and shield bearers cannot carry their armor and shields without pages and servants, and since it is necessary to provide them with pages, each of them requires one page per armor and shield and double bounty. Then there are the handgunners ... These are very practical, set behind the shield-bearers at the start of the battle, before the armies engage, and in defense. Nearly all of the infantry and arbusiers are surrounded by armored soldiers and shield-bearers, as if they were standing behind a bastion. The large shields set together in a circle present the appearance of a fort and similar to a wall in whose defense the infantry and all those among them fight almost as if from behind bastion walls or ramparts and at the given moment break out from it.

— Matthias Corvinus's letter to Gabriele Rangoni,Bishop of Eger[36]

Weaponry

- Melee weapons: Friulian spears, and halberdswere all adapted depending on the social class and nationality of the infantrymen. The 15th-century type of halberd was a transition that mixed an axe blade with an awl-pike, sometimes affixed with a "beak" that was used to pull a knight off his horse and to increase its piercing impact. They were covered with metal langlets on the side to prevent being cut in two.

- Archery: The most valuable archers were the crossbowmen. Their number in Matthias' service reached 4,000 in the 1470s. They used sabres as a secondary weapon (which was unusual for infantry in those ages). Their primary advantage was the ability to shoot heavy armour, while the disadvantages were that they required defense to protect them while moving slowly in a standing position.

- Arquebusiers: These gunpowder troops charged in the early stages of battle. Their aiming ability, price and the danger of primitive hand cannons (self-exploding) prevented them from being highly effective, especially against smaller groups of people or hand-to-hand combat. A distinctive Hungarian feature was that they did not use a fork to stabilize their guns but put it on top of the pavese instead (or in some cases, on the parapet of a wagon). Two types were simultaneously brought to practice, the schioppi (handgun) in the beginning, and later the arquebus à croc (not to be confused with cannons). Three classes of handguns were distinguished: the "bearded" light guns; forked guns; the first primitive muskets (iron tube compounded with wooden grip to be pushed against the shoulder). Their calibers varied from 16 to 24 mm.[30]

- Arsenal

-

Bastard sword

-

Blended crossguarded sword

-

Pavise and halberds

-

Crossbow and accessories

Mutinies

The disadvantage of having periodically or occasionally paid recruits was that if their money had not arrived on time, they simply left the battlefield, or – in a worse scenario – they revolted, as happened in several instances. Since they were the same skilled men-at-arms led by the same leaders previously fighting under the Hungarian flag, they were as difficult to eliminate as the Black Army was to its enemies.[citation needed] However, they could be outnumbered, since it was always a flank or division which quit the campaign. An easier solution was to have the captain accept some lands and castles to be mortgaged in return of service (in one occasion the forts of Ricsó (Hričovský hrad) and Nagybiccse (Bytča) to František Hag).[citation needed] An example of mass desertion occurred in 1481 when a group of 300 horsemen joined the opposing Holy Roman forces.[citation needed] One of these recorded insurrections was conducted by Jan Švehla, who accompanied Corvinus to Slavonia in 1465 to beat the Ottomans; but when they were approaching Zagreb, Švehla asked for royal permission to officially quit the offensive with his mercenaries due to financial difficulty.[citation needed] His request was denied, and as a consequence, he and two of his vice-captains left the royal banner along with their regiments.[citation needed]

Following their breakaway, George of Poděbrady secretly supported their invasion into the

Matthias condemned him to be hanged along with the remaining few hundred prisoners. This was a rather violent act regarding the campaigns of King Matthias Corvinus. On the very next day, 31 January 1467, witnessing the executions, the garrison asked for mercy, and it was granted; and after taking Kosztolány, he also offered František Hag – officer member of the resistance group – captainship in the Black Army, since he found him skilled enough. In another case in 1474, František Hag revolted due to lack of pay, but the conflict ended without violence, and he remained Matthias' subject until his death.[16][38][full citation needed][39]

Dissolution

Before his death on 6 April 1490, King Matthias asked his captains and barons to pledge an oath to his son

Maximilian immediately attacked the conquered territories in Austria in 1490. The Black Army fortified itself in the occupied forts on the western border. Most of them were captured by trickery, bribery, or citizen revolt in a few weeks without any major battles. The trenchline along the river Enns, which was built by mercenary captain Wilhelm Tettauer, resisted quite successfully for a month. Due to lack of payment, some of the Black Army mercenaries, mostly Czechs, switched sides and joined the Holy Roman army of 20,000 men in invading Hungary. They advanced into the heart of Hungary and captured the city of Székesfehérvár, which he sacked, as well as the tomb of King Matthias, which was kept there. His Landsknechts were still unsatisfied with the plunder and refused to go for taking Buda. He returned to the Empire in late December but left garrisons of a few hundred soldiers in those Hungarian cities and castles he occupied.[41]

The National Council of the barons decided to recover the lost cities, especially Székesfehérvár. The Black Army was put in reserve at Eger, but their payment of 46,000 forints was late again, so they robbed the neighboring monasteries, churches, peasants and fiefdoms. After their dues were paid, appointed captain Steven Báthory gathered an army of 40,000 soldiers and began the siege in June 1491, which lasted for a month. More minor cities were recaptured, and without further support from the German nobility, Maximilian agreed to negotiate, and in the end, he signed the Peace of Pressburg in 1491, which included ceding the Silesian lands to him.[41] John Haugwitz never recognized this treaty and held their possessions in Silesia afterwards.[42]

Meanwhile, the disappointed John Albert gathered an army at the eastern border of Hungary and attacked the vicinity of Kassa (Košice) and Tokaj, also in 1490. John Corvinus accepted Vladislaus as his feudal lord and helped him in his coronation (he personally handed the crown to him). Vladislaus married the widowed Queen Beatrice in order to acquire her assets of 500,000 forints. This would have allowed him to cover the expenses of the Black Army stationed in Moravia and upper Silesia and the cost of transporting them home to Upper Hungary to defend it from the Polish army of John Albert.[41] John Filipec, on behalf of the new king, helped to convince Silesian Black Army leader John Haugwitz to return to duty in exchange for 100,000 forints. The Hungarian–Czech army of 18,000 met the Polish troops in December 1491 in the Battle of Eperjes (Prešov), which was a decisive victory for the Black Army.[42] John Albert withdrew to Poland and renounced his claim to the throne.

The Black Army was sent to the south region to fight the Ottoman invasions. While waiting for their wages, they sought plunder in the nearby villages. The National Council ordered Paul Kinizsi to stop the plundering at all costs. He arrived in Szegednic-Halászfalu in late August 1492, where he dispersed the Black Army led by Haugwitz. Of the 8,000 members, 2,000 were able to escape to western

Battles and respective captains of the Black Army

| List of battles and respective captains of the Black Army | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Key

|

Notes

- ^ Žebrák (Hungarian: Zsebrák) is a distinctive historical and military term deriving from the same Czech word meaning beggar. It refers to Czech booty-hunters ravaging the northern regions of Hungary in the 15th century (but would submit themselves to any service for proper pay).[37]

- ^ a b Matthias I was proclaimed king by the Estates, but he had to wage war against Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor who claimed the throne for himself.[64] Several magnates, such as the Újlaki family, the Garai family and the Szentgyörgy family, supported the emperor's claim and proclaimed him king against King Matthias; the emperor rewarded the brothers Sigismund and John of Szentgyörgy and Bazin with the hereditary noble title "count of the Holy Roman Empire" in 1459 and they thus were entitled to use red sealing wax.[64][65] Although the Counts Szentgyörgyi commenced using their title in their deeds, in the Kingdom of Hungary, public law did not distinguish them from other nobles. The tide turned when they were pleased by Matthias' promises, changed their affiliation and joined forces with him. The second battle thus was successful in defending the Hungarian crown and the integrity of the nobility. The precise location of the battle is unknown since the historical records only guess where it could have situated.

- Based upon the aforementioned, the causes of retreat might be (any or multiple):

- Famine caused by siege

- Casimir's disappointment with his former Hungarian allies and frustration that the project became more difficult to carry out

- Agreement of military matters with Matthias on diplomatic grounds (status quo)

- Mediation of the pope and his calling for peace

- Casimir's fear of being captured and Matthias' fear of triggering a possible "official" war with Casimir IV (reason for letting them retreat)

- Intrigue of the nobilityto both sides

- ^ On 7 February 1474, Mihaloğlu Ali Bey's unexpected attack took the town by storm. Ahead of his 7,000 horsemen, he broke through its wooden fences and pillaged the town, burned the houses and took the population as prisoners. Their goal was to rob the treasury of the episcopate, but were resisted by the refugees and clergy in the bishop's castle (at the time the bishop's rank was absent, and no records mention the identity of a possible captain). The town fell but the castle stood, forcing the Turks to give up the fight after one day of siege. While retreating, they devastated the surrounding areas.[84]

- Chynadiyovo surrendered without resistance. The remaining stronghold of Árva had been fortified and Komorovszki defended it himself. The standoff resulted in Matthias' offer of 8,000 gold florins in exchange for the castles, which Komorovszki accepted. He even agreed to let his mercenaries join the Black Army.[87]

- Neumarkt in Steiermark, which was still in the hands of the Holy Roman Emperor. The inhabitants sought protection against the Ottomans and so let Haugwitz's army into the city, successfully repelling the siege. After the relief of the beleaguerment, the Hungarians continued to hold the city until the death of Matthias in 1490[89]

Name variations

| Hungarian (surname, given name) | English (given name, surname) | Ethnolect (given name, surname) |

|---|---|---|

| Hunyadi Mátyás (Mátyás király) | Mat(t)hias Rex, Mat(t)hias Corvin, Mat(t)hias Corvinus, Mat(t)hias Hunyadi, Mat(t)hias Korwin | Czech: Matyáš Korvín, Croatian: Matijaš Korvin, German: Matthias Corvinus, Medieval Latin: Mattias Corvinus, Polish: Maciej Korwin, Romanian: Matia/Matei/Mateiaş Corvin, Serbian: Матија Корвин/Matija Korvin, Slovak: Matej Korvín, Slovene: Matija Korvin, Russian: Матьяш Корвин/Matyash Corvin |

| Magyar Balázs | Balázs/Balazs Magyar, Blaž the Magyar | Croatian:Blaž Mađar, Slovak: Blažej Maďar, Spanish:Blas Magyar, German:Blasius Magyar, Italian:Biagio Magiaro |

| Kinizsi Pál | Paul/Pál Kinizsi | Romanian:Pavel Chinezul, Slovak: Pavol Kiniži, Spanish:Pablo Kinizsi |

| (S)Zápolya(i) Imre, S)Zapolya(i) Imre, Szipolyai Imre | Emeric Zapolya, Emeric Zapolyai, Emeric Szapolya, Emeric Szapolyai, Emrich of Zapolya | Polish: Emeryk Zápolya, Slovak: Imrich Zápoľský, Spanish: Emérico Szapolyai (de Szepes), German: Stefan von Zips |

| Gis(z)kra János | John Giskra, John Jiskra | Czech: Jan Jiskra z Brandýsa, German: Johann Giskra von Brandeis, Italian:Giovanni Gressa, Slovak: Ján Jiskra z Brandýsa |

| Löbl Menyhért | Melchior Löbel, Melchior Loebel, Melchior Löbl, Melchior Loebl | German: Melchior Löbel |

| Haugwitz János | John Haugwitz | German: Johann Haugwitz, Czech: Hanuš Haugvic z Biskupic |

| Báthory István, Báthori István | Stephen V Báthory, Stephen Báthory of Ecsed | Romanian: Ștefan Báthory, German: Stephan Báthory von Ecsed, Italian: Stefano Batore, Slovak: Štefan Bátory |

| Csupor Miklós | Nicolaus Chiupor, Nicolaus Csupor | Romanian: Nicolae Ciupor |

| Jaksics Demeter | Demetrius Jaksic | Serbian: Dmitar Jakšić |

| Újlaki Miklós | Nicholaus of Ujlak, Nicholaus Iločki | Croatian: Nikola Iločki |

| Hag Ferenc | František Hag | Czech: František z Háje, German: Franz von Hag |

| Tettauer Vilmos | Wilhelm Tettauer | Czech: Vilém Tetour z Tetova |

See also

- Austrian–Hungarian War (1477–88)

- Bohemian–Hungarian War (1468–78)

- Battle of Leitzersdorf

- Growth of the Ottoman Empire

- Hussite Wars

- Siege of Hainburg

- Second siege of Hainburg

- Siege of Kaiserebersdorf

- Siege of Retz

- Siege of Vienna (1485)

- Siege of Wiener Neustadt

- Wagon fort

References

- ^ ]

- ^ Valery Rees: Hungary's Philosopher King: Matthias Corvinus 1458–90 (Published 1994) [1]

- ISBN 9780195334036. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ Anthony Tihamer Komjathy (1982). "A thousand years of the Hungarian art of war". Toronto, ON, Canada: Rakoczi Press. pp. 35–36. Archived from the original on 26 January 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Vajna-Naday, Warhistory. p. 40.

- ^ Courtlandt Canby: A History of Weaponry. Recontre and Edito Service, London. p. 62.

- ^ a b c d e István Tringli (1998). "Military History" (CD-ROM). The Hunyadis and the Jagello age (1437–1526). Budapest: Encyclopaedia Humana Association. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ISBN 9780195334036.

- ISBN 978-0-19-533403-6.

- ISBN 978-1317895701.

- ]

- ISBN 9781570037399.

- ISBN 978-1-84668-256-8.

- LCCN 90006426.

- ^ Haywood, Matthew (2002). "The Militia Portalis". Hungarian Armies 1300 to 1492. Southampton, United Kingdom: British Historical Games Society. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ ISBN 978-963-9705-43-2. Archived from the original(PDF) on 20 September 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ ASIN B001B3PZTG. Archived from the originalon 2 March 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- S2CID 259346714. Archived from the original(PDF) on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ ISBN 1-85043-977-X. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ISBN 978-963-9340-68-8.

- ^ Iliescu, Octavian (2002). "C. Transylvania (including Banat, Crişana and Maramureş)". The history of coins in Romania (ca. 1500 BC – 2000 AD). NBR Library Series. Bucharest, Romania: Editura Enciclopedică. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ Beham, Markus Peter (23 July 2009). "Braşov (Kronstadt) in the Defence against the Turks (1438–1479)" (PDF). Vienna, Austria: Kakanien revisited. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Haywood, Matthew (2002). "Wargaming and Warfare in Eastern Europe (1350 AD to 1500 AD )". Mercenary infantry of the Hunyadi era. Southampton, United Kingdom: British Historical Games Society. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). "Matthias I., Hunyadi". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 900–901.

- ^ ISBN 963-327-017-0.

- ^ ISBN 0-521-34315-1. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ "Mátyás király levelei: külügyi osztály" (PDF). mek.oszk.hu (in Hungarian). Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ISBN 978-963-351-696-6.

- ^ Master Mihály (1478). "Frescoes in the Póniky (Pónik) Roman Catholic Church, Slovakia". Archived from the original on 4 November 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ ISBN 963-7663-03-7.

- ^ Jenő Darkó (1938). A magyar huszárság eredete [On the origin of Hungarian hussars] (in Hungarian). István Tisza Scientific Society of Debreceni

- ^ Tóth, Zoltán (1934). A huszárok eredetéről (PDF) (in Hungarian).

- ^ Anonymous (1480–1488). "The Gradual of King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary". Cod. Lat. 424. Archived from the original on 4 November 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ "A Fekete Sereg előadás". aregmultajelenben.shp.hu.

- ISBN 9781570037399.

- ^ Clifford Rogers, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, 2010, p. 152

- ^ Budapest, Hungary: Pallas Irodalmi és Nyomdai Rt. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ "Miért került bitófára Svehla?" [Why was Svehla sent to the gallows?]. pp. 19–24.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ISBN 0-86516-444-4. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- ISBN 963-86118-7-1. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ ISBN 963-86118-7-1. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ ISBN 963-9374-13-X. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ ELTE. Archived from the originalon 19 August 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- Budapest, Hungary: Stádium Sajtóvállalat Rt. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ Budapest, Hungary: Napkút Kiadó. Archived from the originalon 21 July 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ISBN 0-520-02392-7. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ Hermann Markgraf (1881). "Johann II., Herzog in Schlesien" [John II, Duke of Silesia]. Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie 14 (in German). Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ^ ISBN 0-87169-127-2. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- Budapest, Hungary: Országos Széchényi Könyvtár. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ ISBN 978-963-596-542-7. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ ISBN 963-506-040-8. Archived from the originalon 26 March 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ Szapolyai - Lexikon ::. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ Nagyenyed, Hungary: Fiedler Gottfried. p. 247. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ISBN 963-86118-7-1. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ISBN 963-86118-7-1. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ISBN 0-313-33538-9. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ISBN 963-86118-7-1. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-2-253-05575-4. Archived from the originalon 24 July 2010. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ Albert Weber (2021). "The 1476 campaign in Serbia and Bosnia - Vlad's sequel". Medieval Warfare. No. XI.4. pp. 35–37.

- ^ ISBN 1-144-24218-5. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Albert III.". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 497.

- ^ a b Mórocz Zsolt (30 August 2008). "Hollószárnyak a Rába fölött" [Raven wings above the Rába] (in Hungarian). Szombathely: Vas Népe Kiadói Kft. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ ISBN 963-05-2661-1.

- ISBN 963-14-0582-6.

- ISBN 0-87169-127-2. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Szentkláray Jenő (2008). "Temesvár és vidéke" [Timișoara and its surroundings]. Az Osztrák-Magyar Monarchia Irásban és Képben [The Monarchy of Austro-Hungary (presented) in text and pictures] (in Hungarian). Budapest, Hungary: Kempelen Farkas Digitális Tankönyvtár. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ISBN 0-691-01078-1. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-546-87357-3. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^ "Csehország története" [History of the Czechy]. Az Osztrák-Magyar Monarchia írásban és képben [The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in Word and Picture].

- ^ "George of Podebrady". Prague, Czech Republic: Government Information Center of the CR. 26 April 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ISBN 0-86516-444-4. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ "Spilberk Castle". Brno, Czech Republic: Muzeum města Brna. 26 April 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ISBN 978-963-389-970-0. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- ISBN 978-963-389-981-6.

- ^ ISBN 963-506-040-8. Archived from the originalon 5 June 2010. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ISBN 963-389-129-9. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ASIN B001C6WHOI.

- ^ ISBN 963-207-840-3. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f "Kezdőlap". jupiter.elte.hu. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "A jászói vár" [The fortress of Jasov] (in Hungarian). Jasov, Slovakia. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^ a b Karl Nehring (1973). "Vita del re Mattio Corvino" [Life of Matthias Corvinus] (PDF) (in Italian). Mainz, Germany: von Hase & Koehler Verlag. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ^ Delia Grigorescu (11 January 2010). "Vlad the Impaler, the second reign – Part 4". Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- Nagyvárad, Hungary: Episcopate of Várad. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ ISBN 963-86118-7-1. Archived from the originalon 5 July 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ELTE. Archived from the originalon 27 June 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ^ ISBN 963-86118-7-1. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ISBN 963-86118-7-1. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ISBN 978-963-465-183-3. Archived from the originalon 5 March 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- Neumarkt in Steiermark, Austria: Marktgemeinde Neumarkt. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ a b "Zeleny (Selene), ungarischer Hauptmann" [Zeleny (Selene), Hungarian captain]. Regesta Imperii (in German). Mainz, Austria: Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ Hoengseong, South Korea: Korean Minjok Leadership Academy. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ "Geschichte Chronik 987–2009" [History Chronicles 987–2009]. baderlach.gv.at (in German). Bad Erlach, Austria: Marktgemeinde Bad Erlach. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

External links

![]() Media related to Black Army of Hungary at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Black Army of Hungary at Wikimedia Commons