Bohemian Reformation

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

The Bohemian Reformation (also known as the Czech Reformation[1] or Hussite Reformation), preceding the Reformation of the 16th century, was a Christian movement in the late medieval and early modern Kingdom and Crown of Bohemia (mostly what is now present-day Czech Republic, Silesia, and Lusatia) striving for a reform of the Catholic Church. Lasting for more than 200 years, it had a significant impact on the historical development of Central Europe and is considered one of the most important religious, social, intellectual and political movements of the early modern period. The Bohemian Reformation produced the first national church separate from Roman authority in the history of Western Christianity, the first apocalyptic religious movement of the early modern period, and the first pacifist Protestant church.[1]

The Bohemian Reformation included several theological strains that developed over time. or Calixtines.

Together with the

The Bohemian Reformation remained distinct from the German and

History

Origins

The Bohemian Reformation started in

Apart from the university theologians there were also reform preachers, such as

The complete translation of the Bible into Czech in the mid-14th century also contributed to the origin of the Bohemian Reformation. After French and Italian, Czech became the third modern European language in which the whole Bible was translated.[13]

Jan Hus

The best-known representative of the Bohemian Reformation is

When Hus, as a result of an interdict, left Prague for the country, he realized what a gulf there was between university education and theological speculation on one hand, and the life of uneducated country priests and the laymen entrusted to their care on the other.[6] Therefore, he started to write many texts in Czech, such as basics of the Christian faith or preachings, intended mainly for the priests whose knowledge of Latin was poor.[14]

Before Hus left Prague, he decided to take a step which gave a new dimension to his endeavors. He no longer put his trust in an indecisive King, a hostile Pope or an ineffective Council. On 18 October 1412, he appealed to Jesus Christ as the supreme judge. By appealing directly to the highest Christian authority, Christ himself, he bypassed the laws and structures of the medieval Church.

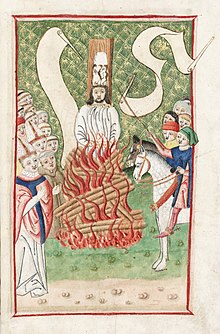

The execution of Jan Hus at the Council of Constance in 1415 led only to a radicalization of Hus's followers.[9] In 1414, Jacob of Mies first served the holy communion under both kinds to laymen (which was forbidden by the Fourth Council of the Lateran in 1215) by the approval of Hus who already dwelt in Constance. Communion under both kinds represented by chalice became the main symbol of the Bohemian Reformation. Up to the present time the chalice is a symbol of non-Catholic Christians in the Czech Republic.[citation needed]

Hussites

After Jan Hus was burnt at the stake, the Bohemian Reformation started to oppose the Council of Constance and later the Pope, and became a distinctive religious movement with its own symbols (chalice), rituals (

Because of the political situation the Hussites were not only a religious group but became also a political and military faction.[16] The ideological and political program shared by the Hussites at the beginning of the Hussite Wars was contained in the Four Articles of Prague, which can be summarized as:

- Freedom to preach the Word of God.

- Freedom of the communion of the chalice (under both kinds also to laity).

- Exclusion of the clergy from large temporal possessions or civil authority.

- Strict repression and punishment of a mortal sin, whether in clergy or in laity.[17]

In the summer of 1419, tens of thousands of people gathered for a massive outdoor religious service on a hill christened Mount Tabor, where the town Tábor was founded. The so-called Taborites practiced a form of communal economy that has been of great interest to Marxist historians.[1]

After the

Bohemian Utraquist Church

The Utraquist Church of Bohemia was an autonomous ecclesial body which emerged in Bohemia and Moravia, that viewed itself as a part of the one, holy,

The church was largely Czech-speaking, although it included some German-speaking parish communities as well. With the emergence of the Protestant Reformation the Utraquist Church found it necessary to define its identity not only in relation to Rome, but also to the reformed churches. During the entire sixteenth century Bohemia and Moravia enjoyed a considerable religious tolerance that was not limited by the principle

The main expression of its confessional distinctiveness was a reformed liturgy that combined Latin and Czech, and practiced communion under both kinds for the laity of all ages, including little children as well as infants. Jan Hus was considered a saint and venerated as a martyr in the cause of a renewal of Christ's Church. However better knowledge of Utraquist theology belongs among the major desiderata of historical scholarship.[19]

Czech (Bohemian, Moravian) Brethren

The

The Unity of the Brethren executed the first Czech Bible translation from the original languages. This work was initiated by Brethren's bishop

The Brethren introduced the sacred song in the vernacular language as a basic element of the church service. Although the Unity of the Brethren was just a small religious group, its contribution for the development of the Czech monophonic sacred song is indisputable. Their first hymnal (in Czech) was printed in 1501 as the first printed hymnal in the whole Christian world (containing 89 hymns without tunes). During the 16th and early 17th century, the Unity became the foremost producer of hymns in Czech lands. The Unity printed some eleven different hymnals (in 28 publications) in Czech, German, and Polish, most including tunes as well as words. The first German-language Unity hymnal edited in 1531 by Michael Weisse had 157 hymns with tunes. In 1541 Jan Roh edited a new Czech hymnal containing 482 hymns with tunes, and in 1544, he issued a new revised edition of the German hymnal of 1531. Unity's best known Czech-language hymnbooks were printed in Ivančice (1561) and Szamotuły (1564) under the supervision of Jan Blahoslav.[21] The hymnal of 1561 contained 735 hymn texts and over 450 melodies. That makes the importance of hymn singing in the Unity very clear.[22] The Bohemian Brethren later also used the Genevan Psalter translated into Czech by Jiří Strejc in 1587.

Apart from Jan Blahoslav, other famous theologians of the Unity were

References

- ^ a b c Atwood, Craig D. "Czech Reformation and Hussite Revolution". www.oxfordbibliographies.com. Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Kruh českých duchovních tradic". veritas.evangnet.cz (in Czech). VERITAS – historická společnost pro aktualizaci odkazu české reformace. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ Soukup, Miroslav (2005). "Cesta k české reformaci" (PDF) (in Czech). Ústí nad Labem. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ "Turistická cesta valdenské a české reformace" (PDF) (in Czech). Veritas. 2005. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ^ Morée, Peter C. A. (2011). "Česká reformace u nás v cizině". www.christnet.eu (in Czech). Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ ISBN 978-80-200-1879-3.

- ISBN 978-3-05-009343-7.

- ISBN 978-80-7321-651-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-80-200-1879-3.

- ISBN 978-80-257-0186-7.

- ISBN 978-80-200-1879-3.

- ISBN 978-80-87057-11-7.

- ISBN 80-86196-33-X.

- ISBN 978-80-257-0875-0.

- ^ "Magistri Ioannis Hus appelatio ad supremum iudicem". etfuk.sweb.cz. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- ^ Cf. Williamson, Allen. "Joan of Arc Letter of March 23, 1430". Joan of Arc Archive. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ Gillett, E. H. (1864). The life and times of John Huss: or, The Bohemian reformation of the fifteenth century. Band 2. Boston: Gould and Lincoln. p. 437. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-7393-3. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-80-86675-11-4. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ David, Zdeněk V. (2007). "Utraquism's Liberal Ecclesiology". Bohemian Reformation and Religious Practice. 6: 165.

- ^ Settari, Olga (1994). "The Czech sacred song from the period of the Reformation" (PDF). Sborník prací filozofické fakulty brněnské univerzity. Studia minora facultatis philosophicae universitatis Brunensis. H 29.

- ISBN 9781580462600.

Bibliography

- Betts, R. R. (April 1947). "The place of the Czech reform movement in the history of Europe". The Slavonic and East European Review. 25 (65).

- Brown, M. T. (2013). John Blahoslav – Sixteenth-Century Moravian Reformer Transforming the Czech Nation by the Word of God. Bonn: Verlag für Kultur und Wissenschaft. ISBN 978-3-86269-063-3.

- David, Zdeněk V. (2003). Finding the middle way : the Utraquists' liberal challenge to Rome and Luther. Baltimore (Md.): the J. Hopkins university press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7382-9.

- Fudge, Thomas A. (1998). The magnificent ride : the first reformation in Hussite Bohemia. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-85928-372-1.

- Fudge, Thomas A. (2010). Jan Hus Religious Reform and Social Revolution in Bohemia. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. ISBN 978-0-85771-855-6.

- Fudge, Thomas A. (2016). Jerome of Prague and the Foundations of the Hussite Movement. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190631550.

- Gillett, E. H. (1863). The life and times of John Huss: or, The Bohemian reformation of the fifteenth century. Volume 1. Boston: Gould and Lincoln.

- Gillett, E. H. (1864). The life and times of John Huss: or, The Bohemian reformation of the fifteenth century. Volume 2. Boston: Gould and Lincoln. ISBN 9781407753232.

- Grant, Jeanne (2014). For the Common Good : The Bohemian Land Law and the Beginning of the Hussite Revolution. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004283268.

- Haberkern, Phillip N. (2016). Patron Saint and Prophet: Jan Hus in the Bohemian and German Reformations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190613976.

- Kaminsky, Howard (2004). A history of the Hussite revolution. Eugene, Or.: Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59244-631-5.

- McBride, Stephen Turnbull ; illustrated by Angus (2004). The Hussite Wars 1419–36. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84176-665-2. Archived from the original on 2016-04-24. Retrieved 2015-01-26.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - Zeman, J. K. (1973). "The Rise of Religious Liberty in the Czech Reformation". Central European History. 6 (2): 128–147. S2CID 145651918.