Bone Sharps, Cowboys, and Thunder Lizards

LC Class | QE707.C63 O88 2005 | |

Bone Sharps, Cowboys, and Thunder Lizards: A Tale of Edward Drinker Cope, Othniel Charles Marsh, and the Gilded Age of Paleontology is a 2005

Ottaviani grew interested in the time period after reading a book about the Bone Wars. Finding Cope and Marsh unlikeable and the historical account dry, he decided to fictionalize events to service a better story. Ottaviani placed the artist Charles R. Knight into the narrative as a relatable character for audiences. The novel was the first work of historical fiction Ottaviani had written; previously he had taken no creative license with the characters depicted. Upon release, the novel generally received praise from critics for its exceptional historical content, and was used in schools as an educational tool.

Plot summary

Some time later, bone hunter John Bell Hatcher has taken to gambling, as Marsh is not providing him with enough funds. Marsh lobbies the Bureau of Indian Affairs on behalf of Red Cloud, but also visits with the USGS, insinuating that he would be a better leader than Cope. After learning about Sam Smith's attempted sabotage of Cope and once again receiving no payment from Marsh, Hatcher leaves his employ. Marsh, now representing the survey, heads west with wealthy businessmen, scoffing at the financial misfortunes of Cope, whose investments have failed.

Cope travels with Knight to Europe; Knight with the intention of visiting Parisian zoos, Cope with the intent of selling off much of his bone collection. Cope has spent much of his money buying The American Naturalist, a paper in which he plans to attack Marsh. Hatcher arrives in New York to talk about the find Laelaps; in his speech, he hints at the folly of Marsh's elitism and Cope's collecting obsession. Marsh learns that his USGS expense tab (to which he had been charging drinks) has been withdrawn, his publication has been suspended, and the fossils he found as part of the USGS are to be returned to the Survey. His colleagues now shun him, the Bone Wars feud having alienated them. He is forced to go to Barnum to try to obtain a loan.

Osborn and Knight arrive at Cope's residence to find the paleontologist has died of illness. The funeral is attended only by the two friends and a few

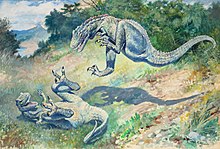

Years later Knight and his wife are taking their granddaughter Rhoda to the American Museum of Natural History. Knight is visiting the new mammoth specimens: the girl, however, is eager to see more of her grandfather's paintings. Meanwhile, the staff are sorting Marsh's long-neglected collection of fossils. Two of the workers discover Knight's Leaping Laelaps has been accidentally left in the storeroom. The painting is taken back downstairs while the workmen leave Cope's and Marsh's bones behind.

Development

Jim Ottaviani published his first graphic novel in 1997,[2] and conceived the idea for Bone Sharps while working his day job as a librarian at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Ottaviani's job included purchasing books for engineering topics, but a new book about the Bone Wars caught his eye. He bought the book himself and found himself fascinated by the rivalry between Cope and Marsh.[3][4] He described his process as spending time doing research, before turning an outline and timeline into a structured story.[5] Using the book as a starting point, Ottaviani read the accounts and biographies of Cope and Marsh as well as other period sources. During the course of his research Ottaviani found the then-unpublished autobiography of Charles Knight. The book inspired him to make the book into a work of historical fiction, something Ottaviani had not done in previous non-fiction books and comics on scientific figures. "I found the whole 'war' aspect [of the Bone Wars] over-hyped," Ottaviani recalled. "These guys never came to blows, or even did anything that went very far beyond questionable ethics."[4] In comparison to his previous works, Ottaviani called the scientists "the bad guys".[6]

While the majority of Bone Sharps is true and all of it is based on history, Ottaviani took liberties throughout to better serve the story.[4] In real life, Knight did not meet Cope until only a few years before Cope's death; In addition, Knight's autobiography states that it was reporter William Hosea Ballou who introduced the two, not Osborn.[4][7] There is also no evidence Marsh and Knight ever met. On Knight's role in the story, Ottaviani wrote:

As I was reading about Cope and Marsh, I ran across Knight as something of a bit player in their lives. As I got further into the Cope and Marsh story, and I liked the two less and less as people—which is different from liking them as characters, of course—I wanted to have a character in the book for the readers to root for, and neither of the scientists could fill that role. When I found out that Knight had met Cope just before Cope died, I became convinced that he was the character I needed.[8]

Ottaviani's interest in Knight eventually led to his company G.T. Labs publishing Knight's autobiography, with notes by Ottaviani and forewords by Ray Bradbury and Ray Harryhausen.[8] Other character relationships were fictionalized as well: editor James Gordon Bennet, Jr. never lobbied with Cope, and never exposed Marsh's will. Cope's bones also never made it to New York.[9] Some conversations, due to their private nature, were fictionalized; Ottaviani makes up Marsh's lobby to Congress and what happened during his meeting with President Grant, and P.T. Barnum never told off Marsh the way he did in the novel.[10] Ottaviani wove the story Marsh tells about the Mastodon from several different versions of the legend.[11] A key plot point is fabricated for the purposes of dramatic irony: in the book, Marsh has his agent Sam Smith leave a Camarasaurus skull for Cope to find and mistakenly put on the wrong dinosaur. Instead, Hatcher finds it; Smith tries to keep an unwitting Marsh from getting it, but due to Marsh's obnoxious manner he lets him after all. As a result, Marsh mistakenly classifies the (non-existent) Brontosaurus. Ottaviani wholly invented this scene, as "The literary tradition of hoisting someone up by his own petard was too good to pass up."[1]

While Ottaviani was putting his ideas together, he met

Reception

The book was generally well-received upon release. Comic book letterer Todd Klein recommended the book to his readers, stating that the novel was able to convey the depths of Cope and Marsh's rivalry and "we can only wonder how much more could have been accomplished if [Cope and Marsh] had only been willing to team up instead".[12] Klein's complaints focused on stiff art and the difficulty in telling some characters apart, but said these shortcomings did not affect the flow and reading.[12] Johanna Carlson of Comics Worth Reading found Bone Sharps's central message, "the question of whether promotion is a necessary evil (to gather funds through attention) or a base desire of those with the wrong motivations", still relevant to today's society; Carlson lauded the flow of the novel and some of the intricate details in the story and setting.[13] Other reviewers praised Ottaviani's inclusion of notable historical figures,[8] the educational yet entertaining feel of the work,[14] and expressive artwork.[15]

In addition to minor issues with the art, Entertainment Weekly's Tom Russo felt that more fiction could have been used in the mostly non-fiction writing.[16] In contrast, Peter Guitérrez felt that given Ottaviani's liberties with conversations the book veered too far into fiction at points; the book's inclusion of an "exhaustive" appendix to separate reality from creative liberties was welcomed.[17] Kirkus Reviews recommended the book to adults and children interested in scholarly dinosaur information.[18]

Due to the historical background of the book, Bone Sharps was used in schools, as part of a study testing the effects of using comic books to educate young children.[19] Author and professor Karen Gavigan recommended the book and Ottaviani's other work as a way to make the lives of famous scientists more accessible and offering chances for critical thinking.[20] Ottaviani followed Bone Sharps with other lightly-fictionalized historical stories, including Levitation: Physics and Psychology in the Service of Deception and Wire Mothers: Harry Harlow and the Science of Love.[21]

References

- ^ ISBN 9780966010664.

- ISSN 1542-4715.

- ^ a b c Wolk, Douglass (October 11, 2005). "Dinosaurs and Cowboys". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ The Comics Reporter. Archivedfrom the original on July 19, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2007.

- ^ Rode, Mike (September 30, 2011). "Meet a Visiting Cartoonist: A Chat with Jim Ottaviani". Washington City Paper. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- ^ Fox, Carol (October 1, 2005). "Cowboys, Dinosaurs, Heisenberg and Bohr". Sequential Tart. Archived from the original on July 15, 2007. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ISBN 9780966010688.

- ^ a b c Mondor, Colleen (January 1, 2006). "Comic Books and Thunder Lizards". Book Slut. Archived from the original on April 22, 2015. Retrieved January 20, 2008.

- ISBN 9780618082407.

- ISBN 9780517707609.

- ISBN 9780815606390.

- ^ a b Klein, Todd (August 15, 2007). "And Then I Read: Bone Sharps, Cowboys And Thunder Lizards". Klein Letters. Archived from the original on September 21, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ^ Carlson, Johanna (March 25, 2006). "Bone Sharps, Cowboys, and Thunder Lizards". Comics Worth Reading. Archived from the original on April 2, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ^ Agamemnon, Bob (May 8, 2005). "Sunday Slugfest: Previews". Comics Bulletin. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved February 1, 2008.

- ^ Staff. "Fiction Book Review: Bone Sharps, Cowboys, and Thunder Lizards". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- ^ Russo, Tom (October 14, 2005). "Book Review: Bone Sharps, Cowboys, and Thunder Lizards". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 12, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ISSN 0362-8930.

- ISSN 1948-7428.

- National Public Radio. Archivedfrom the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved February 1, 2008.

- ISSN 1481-1782.

- ^ Jordan, Justin (May 24, 2007). "Science of the Unscientific with Jim Ottaviani | CBR". Comic Book Resources. Valnet. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

External links

- Bone Sharps, Cowboys, and Thunder Lizards Preview at G.T. Labs