Banate of Bosnia

| Banate of Bosnia Boszniai Bánság ( Serbo-Croatian) Banovina Bosna | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banate of the Kingdom of Hungary | |||||||||

| 1154–1377 | |||||||||

King of Bosnia | 1377 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

| History of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

|---|

|

|

|

The Banate of Bosnia (

Historical background

In 1136, Béla II of Hungary invaded upper Bosnia for the first time and created the title "Ban of Bosnia", initially only as an honorary title for his grown son Ladislaus II of Hungary. During the 12th century, rulers within the Banate of Bosnia acted increasingly autonomously from Hungary and/or Byzantium. In reality, outside powers had little control of the mountainous and somewhat peripheral regions which made up Bosnian Banate.[6]

History

Early history and Kulin

In the time of emperor Manuel I Komnenos death (1180), Bosnia was governed by Ban Kulin who managed to free it from Byzantine influence through the alliance to Hungarian king Béla III, and with help of Serbian ruler Stefan Nemanja and his brother Miroslav of Hum, with whom he successfully waged a war in 1183 against the Byzantines. Kulin secured peace, although it continued as a nominal vassal to Hungarian king.[14] but there is no evidence that Hungarians occupied areas of central Bosnia.[13]

The Pope emissaries of that time reached to Kulin directly and referred to him as "lord of Bosnia".[14] Kulin was often referred as "veliki ban bosanski" (Great Bosnian Ban) by contemporaries, and by his successor Matej Ninoslav.[14] He had a powerful effect on the development of early Bosnian history, under whose rule an age of peace and prosperity existed.[15]

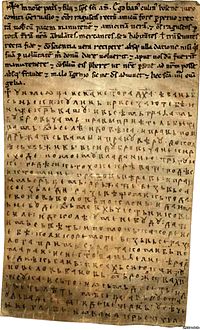

In 1189, Ban Kulin issued the first written Bosnian document, now known as the

Heresy and Bilino Polje abjuration

In 1203, Serbian Grand Prince

The Bosnian Church forcibly replaced Kulinić with a nobleman called

Bosnian Crusade

The

It was also a response due to the very bad relations between Bosnia and Serbia,[

The remainder of his reign, Ban Ninoslav Matej dealt with inner matters in Bosnia. His death after 1249, possibly in 1250, brought some conflicts over the throne; as the Bosnian Church desired someone from their own sphere of interest, and the Hungarians side desired someone that they could easily control. Eventually, King Bela IV conquered and pacified Bosnia and succeed in putting Ninoslav 's Catholic cousin Prijezda as the Bosnian Ban. Ban Prijezda ruthlessly persecuted the Bosnian Church. In 1254 the Croatian Ban shortly conquered

Another Hungarian campaign was launched against Bosnia in 1253, but there was no evidence that they reached the Bosnian Banate. However, Hungary did control northern regions of Usora and Soli through their vassal rulers. Bosnian banate continued to exist as de facto independent entity even after Ninoslav.[23]

Kotromanić dynasty

Prijezda I's realm (founder of

Hungarians reasserted their authority over territories as Soli, Usora, Vrbas, Sana in the early 13th century. Territory that Ban Prijezda, a loyal Hungarian vassal, controlled was possibly in northern parts of today's Bosnia between rivers Drina and Bosna. Banate of Bosnia to the south remained independent, but we do not know its rulers, successors of ban Ninoslav.[25]

He was inherited by

Restoration and Expansion

During the end of the 13th and about the first quarter of the 14th century, till the

Stephen II was the

By 1326 Ban Stephen II attacked Serbia in a military alliance with the

In 1329, Ban Stephen II Kotromanić pushed another military attempt into Serbia, assaulting Lord Vitomir of Trebinje and Konavle, but the main portion of his force was defeated by the Young King Dušan who commanded the forces of King Stefan Dečanski at Priboj. The Ban's horse was killed in the battle, and he would have lost his life if his vassal Vuk had not given him his own horse. By doing so, Vuk sacrificed his own life, and was killed by the Serbian troops in open battle. Thus the Ban managed to add Nevesinje and Zagorje to his realm.[citation needed]

Throughout his reign in the fourteenth century, Stephen ruled the lands from

In 1346 Zadar finally returned to Venice, and the Hungarian King, seeing that he had lost the war, made peace in 1348. Ban of Croatia

Tvrtko I reign

Tvrtko, however, was only about fifteen years old at the time,

At the start of his personal rule the young Ban somehow considerably increased his power. The anarchy escalated, and in February the following year, the magnates revolted against Tvrtko and dethroned him.[36][40] He was replaced by his younger brother Vuk,[40][36] Tvrtko and Jelena took refuge at the Hungarian royal court, where they were welcomed by Tvrtko's former enemy and overlord, King Louis.[36] Tvrtko returned to Bosnia in March and reestablished control over a part of the country by the end of the month, including the areas of Donji Kraji, Rama (where he then resided), Hum, and Usora.[41][42]

Throughout the following year, Tvrtko forced Vuk southwards, eventually compelling him to flee to Ragusa. Sanko, Vuk's last supporter, submitted to Tvrtko in late summer and was allowed to retain his holdings.[36][43] Ragusan officials made an effort to procure peace between the feuding brothers,[43] and in 1368, Vuk asked Pope Urban V to intervene with King Louis I on his behalf.[36][43] Those efforts were futile; but by 1374, Tvrtko had reconciled with Vuk on very generous terms.[43]

The death of

By the mid-14th century, Bosnian banate reached its peak under young ban Tvrtko Kotromanić who came into power in 1353, and had himself crowned on 26 October 1377.[44]

Economy

The second

The export of metal ores and metalwork (mainly silver, copper and lead) formed the backbone of the Bosnian economy, as these goods along others like wax, silver, gold, honey and rawhide were transported over the Dinaric Alps to the seashore by Via Narenta, where they were bought chiefly by the Republics of Ragusa and Venice.[47] Access to Via Narenta was crucial for Bosnian economy, which was possible only after ban Stephen II managed to take control of the trading route during his conquests of Hum. The main trading centres were Fojnica and Podvisoki.

Religion

Christian missions emanating from

While Bosnia remained at least nominally Catholic in the

List of rulers

- Ladislaus II of Hungary (1137—1159)

- Ban Borić (1154—1164)

- Ban Kulin (1180—1204)

- Stephen Kulinić (1204—1232)

- Matej Ninoslav (1232—1250)

- Prijezda I(1250—1287)

- Prijezda II(1287—1290)

- Stjepan I Kotromanić(1287—1314), together with Prijezda II 1287—1290, as a vassal ban 1290—1314

- Mladen I Šubić of Bribir (1299—1304)

- Mladen II Šubić of Bribir(1304—1322)

- Stjepan II Kotromanić(1314—1353), as vassal ban 1314—1322, independently 1322—1353

- Tvrtko I Kotromanić(1353—1366)

- Vuk Kotromanić (1366—1367)

- Tvrtko I Kotromanić(1367—1377)

References

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 44, 148.

- ^ Paul Mojzes. Religion and the war in Bosnia. Oxford University Press, 2000, p 22; "Medieval Bosnia was founded as an independent state by Ban Kulin (1180-1204).".

- ^ a b Vego 1982, p. 104.

- ISBN 978-0-691-00175-3.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 433–434.

- ^ a b c d Fine 1994, p. 14.

- ISBN 9788639901042.

- ISBN 978-9958-9844-0-2.

- ^ Mladen ANČIĆ, 1997, Putanja klatna. Ugarsko-hrvatsko kraljestvo i Bosna u XIV. stoljeću. Zavod za povijesne znanosti Hrvatske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti u Zadru. https://www.bib.irb.hr/40904#page=55

- ^ Goldstein, Ivo. (1997), Bizantska vlast u Dalmaciji od 1165. do 1180. godine, http://darhiv.ffzg.unizg.hr/id/eprint/6319/#page=18

- ISBN 978-9985-9642-5-5. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

U ratu što ga je protiv cara Emanuela vodio kralj Gejza II., sudjelovao je i ban Borić (1154.-1163.), prvi poznati bosanski ban. Borićevo sudjelovanje u ratu na strani ugarsko-hrvatskog vladara svjedoči da je Bosna u to doba za-konito pripadala Ugarsko-Hrvatskom Kraljevstvu. Bizantski je pisac Cinam opisao taj rat i izričito naveo da je bosanski ban bio saveznik ugarsko-hrvat-skog vladara. Taj je rat trajao osam godina (1148.-1155.), a završio je pobjedom ugarsko-hrvatske vojske u blizini Beograda. (Ban Borić (1154-1163), the first known Bosnian ban, also participated in the war that was fought against Emperor Emanuel by king Géza II. Borić's involvement in the war on the part of the Hungarians meant that Bosnia was in vassal relation to the Hungarian ruler at the time. The Byzantine writer Cinam [John Kinnamos] described the war and explicitly stated that the Bosnian ban was an ally of its Hungarian counterpart. This war lasted eight years (1148-1155) and ended with the victory of the Hungarian-Croatian army near Belgrade.)

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 646.

- ^ a b Fine 1994, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Vego 1982, p. 105.

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 17–21.

- ^ Suarez, S.J. & Woudhuysen 2013, pp. 506–07.

- ISBN 978-0814755617.

- ^ a b Fine 1994, p. 47.

- ^ Mladen ANČIĆ, 1997, Putanja klatna. Ugarsko-hrvatsko kraljestvo i Bosna u XIV. stoljeću. Zavod za povijesne znanosti Hrvatske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti u Zadru. https://www.bib.irb.hr/40904#page=60

- ISBN 0472082604

- ISBN 0472082604

- ISBN 978-0863565038

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 148.

- ^ Ćirković 1964, p. 75.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 275, Bosnia from the 1280s to the 1320s.

- ^ Mladen ANČIĆ, 1997, Putanja klatna. Ugarsko-hrvatsko kraljestvo i Bosna u XIV. stoljeću. Zavod za povijesne znanosti Hrvatske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti Zadru.https://www.bib.irb.hr/40904#page=103

- ^ a b c Fine 1994, p. 277.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 275.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 278.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 20.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 280.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 281.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 284.

- ^ a b Ćirković 1964, p. 122.

- ^ Ćošković 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Fine 1994, p. 369.

- ^ Ćirković 1964, p. 125.

- ^ a b Ćirković 1964, p. 128.

- ^ a b c Ćirković 1964, p. 129.

- ^ a b Ćirković 1964, p. 130.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 370.

- ^ Ćirković 1964, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d Ćirković 1964, p. 132.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 81.

- ^ Franz Miklosich, Monumenta Serbica, Viennae, 1858, p. 8-9.

- ISBN 9780791456378.

- ^ Ćirković 1964, p. 141.

- ^ a b c d Fine 1991, p. 8.

- ^ a b Fine 1994, p. 17.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 18.

- ^ "Bosna Srebrena u prošlosti i sadašnjosti | FMC Svjetlo riječi". Svjetlorijeci.ba. Archived from the original on 2014-02-24. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 281, 282.

Sources

- ISBN 9782911527104.

- ISBN 9781405142915.

- Ćirković, Sima (1964). Istorija srednjovekovne bosanske države [History of the medieval Bosnian state] (in Serbo-Croatian). Srpska književna zadruga.

- Ćošković, Pejo (2009). Kotromanići (in Serbo-Croatian). Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ISBN 0472081497.

- ISBN 0472082604.

- ISBN 9788639901042.

- ISBN 9780814755204.

- Orbini, Mauro (1601). Il Regno de gli Slavi hoggi corrottamente detti Schiavoni. Pesaro: Apresso Girolamo Concordia.

- Орбин, Мавро (1968). Краљевство Словена. Београд: Српска књижевна задруга.

- Suarez, S.J., Michael F.; Woudhuysen, H.R. (2013). "The History of the Book in the Balkans". The Book: A Global History. ISBN 978-0-19-967941-6.

- ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- Vego, Marko (1982). Postanak srednjovjekovne bosanske države. Sarajevo: Svjetlost.