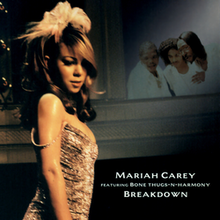

Breakdown (Mariah Carey song)

| "Breakdown" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Mariah Carey featuring Bone Thugs-n-Harmony | ||||

| from the album Butterfly | ||||

| A-side | "My All" | |||

| Released | January 1998 | |||

| Recorded | 1997 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Composer(s) | ||||

| Lyricist(s) |

| |||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| Mariah Carey singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Bone Thugs-n-Harmony singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Breakdown" on YouTube | ||||

"Breakdown" is a song recorded by American singer

Critics judged "Breakdown" in relation to Carey's previous work and considered the collaboration with Bone-Thugs-n-Harmony successful. Some perceived it to be about the recent separation from her husband

Carey directed the music video with previous collaborator Diane Martel. It presents her in various roles at a casino such as a showgirl and cabaret performer; the latter received comparisons to Liza Minnelli. "Breakdown" received heavy rotation on the television channels BET and MTV and was issued as a video single. Clips accompanied Carey's live performances of the song during the 1998 Butterfly World Tour. Retrospectively, "Breakdown" is regarded as a turning point in Carey's musical direction toward hip hop and as one of the best songs of her career.

Background

In the early 1990s, American singer

Experiencing creative freedom,

Composition

Situated among ballads (e.g. "

Columbia chartered a plane to

"Breakdown" concerns concealing heartbreak after a romantic relationship ended due to rejection.[30][31][32] Some of Carey's lyrics, such as "Well I guess I'm trying to be nonchalant about it / And I'm going to extremes to prove I'm fine without you", are directed at the former partner.[33] Others posit questions about how to move on: "So what do you do when / Somebody you're so devoted to / Suddenly just stops loving you?"[34] The lyrics have a dark tone,[35] and chirping birds in the background elicit an optimistic aura.[31] Some critics thought the song detailed the end of Carey's marriage with Mottola.[d] Others felt the perceived references were not as clear.[38][39] Carey told The Boston Globe it is a representation of her admiration for Bone-Thugs-n-Harmony's rapping style.[24]

The

Release

"Breakdown" is the sixth track on Butterfly, which Sony Music issued on September 10, 1997.[51] Upon the album's release, American newspaper critics deemed "Breakdown" a potentially successful single.[e] R&B radio stations in the country began playing it in late 1997 amid a lukewarm response to the album's second single, "Butterfly".[f] After "Breakdown" received over 600 spins without promotion,[59] Columbia released the song to American rhythmic contemporary radio stations in January 1998.[22][57] It was the third single from Butterfly, following "Honey" and "Butterfly".[55]

After "Breakdown" failed to garner crossover success on contemporary hit radio, Columbia did not release it for sale in the United States.[57] At the time, Billboard Hot 100 chart rules stipulated that songs required retail releases to appear and that airplay from R&B radio stations was not a factor.[60] During an interview in late 1998, Carey said Columbia had a peculiar pattern of not releasing her heavily R&B material as commercial singles since her 1990 debut: "I'll always be upset 'Breakdown' never got its shot."[61]

Columbia released "Breakdown" in the United States as a

Critical reception

Critics evaluated the effectiveness of "Breakdown" as a departure from Carey's previous work. Billy Tyus described it as innovative in the Herald & Review,[72] and Daily Herald writer Mark Guarino considered the lyrics surprisingly serious.[73] Paul Willistein of The Morning Call and author Chris Nickson believed "Breakdown" demonstrated artistic freedom successfully.[74][75] Carey's restrained vocals made the song as high-quality as her traditional ballads according to Vulture's Lindsey Weber.[76] In contrast, several critics thought the composition lacked cohesiveness.[h] Writing in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Dave Tianen said Carey's "vocals get smothered beneath a rancid glop of synths, samples, raps and choruses".[80] Nicole M. Campbell of The Santa Clarita Valley Signal credited these sentiments to the number of producers, which she considered excessive.[81]

The song received comparisons to others in its genre. According to

Critics praised the pairing of Carey and Bone Thugs-n-Harmony.[k] Slant Magazine's Sal Cinquemani thought Carey wholly embraced her collaborators' appearance on the track.[48] According to Sonia Murray of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, she adopted their cadence without losing authenticity.[90] For New York Daily News writer Jim Farber, "instead of just co-opting their sound, her sweet tones give Bone Thugs' sound a new fluidity."[41] In contrast, The Scotsman's Sarah Dempster considered the collaboration confounding.[91] Richard Harrington of The Washington Post thought Bone Thugs-n-Harmony overshadowed Carey;[39] J. D. Considine of The Baltimore Sun said she adopted their style so effectively that the group's presence was almost unnecessary.[36]

Commercial performance

"Breakdown" experienced success on American

After the double A-side release with "My All", "Breakdown" debuted and peaked at number four on the

The song's performance varied in other countries. "Breakdown" peaked at number four on the

Music video

Carey and

The "Breakdown" music video was issued in late 1997.

Legacy

Critics judge "Breakdown" as a turning point in Carey's musical direction toward hip hop.

Retrospectively, Carey and her fans consider "Breakdown" one of the best songs in her catalog.

| Publication | List | Year | Rank | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Billboard | 100 Greatest Mariah Carey Songs | 2020 | 18 | [47] |

| Butterfly Tracklist Ranked | 2022 | 5 | [19] | |

| Mariah Carey's 56 Best Collaborations with Rappers | 2019 | 6 | [129] | |

Cleveland.com

|

All 76 Mariah Carey Singles Ranked | 2020 | 11 | [88] |

Complex

|

Stevie J's 10 Greatest Music Contributions | 2014 | Placed | [130] |

| Dazed | Mariah Carey's 10 Greatest Hip Hop Collaborations | 2015 | Placed | [131] |

| Revolt | Stevie J's 11 Most Classic Beats | 2019 | 3 | [132] |

| Vibe | Butterfly Tracklist Ranked | 2017 | 2 | [40] |

| Vulture | Mariah Carey's 25 Best Singles | 2014 | 11 | [76] |

Credits and personnel

- Mariah Carey – background vocals, composer, lyrics, producer, vocals

- Dana Jon Chappelle – engineering

- Sean "Puffy" Combs– producer

- Ian Dalsemer – assistant engineering

- Anthony Henderson – background vocals, lyrics, vocals

- Steven Jordan – composer, keyboards, keyboard and drum programming, producer

- Tony Maserati – mixing

- Herb Powers Jr. – mastering

- Charles Scruggs – background vocals, lyrics, vocals[23]

Charts and certifications

|

|

Notes

- ^ According to Norman Abjorensen, "middle of the road" is a radio format focusing on songs that are "generally strongly melodic and often features vocal harmony technique and light orchestral arrangements".[1]

- ^ Their separation occurred in late 1996,[5] and was disclosed publicly on May 30, 1997.[6]

- ^ Daddy's House was a recording studio owned by Sean Combs[28]

- ^ Such as J. D. Considine of The Baltimore Sun,[36] Michael Corcoran of the Austin American-Statesman,[35] and David Thigpen of Time[37]

- ^ Such as those from USA Today,[52] The Philadelphia Inquirer,[53] and the Springfield News-Leader[54]

- radio programmer told Billboard that they added "Breakdown" to their playlist instead of "Butterfly" to avoid playing multiple slow songs in a row.[58]

- ^ For comparison, when "Breakdown" debuted on the Hot R&B Singles chart dated May 9, 1998, none of the other ninety-nine songs on the chart had as many formats available.[63]

- ^ Such as Gary Graff of the San Francisco Chronicle,[77] Chuck Campbell of the Knoxville News Sentinel,[78] and Dave Ferman of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram[79]

- ^ Ferman felt that unlike R&B collaborations before the 1990s, in which "individual styles and good material blended to produce something that neither artist could have managed alone," the new "sound is an often unsatisfying fusion of slow to medium beats, with traces of '70s funk and a more streetwise sensibility than much ultra-successful '80s urban music had".[82]

- ^ Such as Jon O'Brien and Christine Werthman of Billboard[19][47]

- ^ The release was credited to "My All"/"Breakdown" by the next week[98]

- ^ "Butterfly" peaked at number fifteen[66]

- ^ "The Roof (Back in Time)" was chosen as the third single from Butterfly in the United Kingdom in lieu of "Breakdown", but its release was ultimately cancelled. "My All" was issued independently of "Breakdown".[103]

- ^ Such as writers for NPR,[118] Slant Magazine,[119] and Vibe[40]

- ^ Such as those from Billboard,[47] Cleveland.com,[88] and Vulture[76]

References

- ^ Abjorensen 2017, p. 337

- ^ Nickson 1998, p. 3

- ^ Shapiro 2001, p. 92

- ^ Nickson 1998, p. 146

- ^ Shapiro 2001, p. 98

- ^ Reilly, Patrick M. (June 2, 1997). "Sony Official, Mariah Carey Disclose Plans to Separate". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 13, 2022.

- ^ Nickson 1998, pp. 24, 26

- ^ Shapiro 2001, p. 109

- ^ Frank, Alex (November 28, 2018). "Forever Mariah: An Interview with an Icon". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on November 7, 2023.

- ^ Nickson 1998, p. 164

- ^ Chan 2023, p. 78

- ^ Life After Death (CD liner notes). Puff Daddy Records. Arista Records. 1997. 78612 73011 2.

- ^ a b c d e Littles, Jessica (October 26, 2020). "20 Years Later: The Secret History of Mariah Carey's Butterfly Album". Essence. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022.

- ^ Nickson 1998, p. 163

- ^ Bronson 1997, p. 841

- ^ Johnson, Kevin C. (March 15, 2019). "6 Highs and 6 Lows on Mariah Carey's Roller-Coaster Career". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023.

- ^ a b Nickson 1998, p. 167

- ^ a b Goldstein, Sjarif (November 16, 2016). "Pop Queen Mariah Carey Set to Play 3 Shows in Honolulu". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e O'Brien, Jon (September 16, 2022). "Mariah Carey's Butterfly at 25: All the Tracks Ranked". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022.

- ^ Hal Leonard 1997, p. 37

- ^ "Mariah Carey: Butterfly". Sony Music Store. Archived from the original on September 5, 2002.

- ^ ProQuest 1505960992.

- ^ a b c d e Butterfly (CD liner notes). Columbia Records. 1997. CK 67835.

- ^ Newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 2860524569.

- ^ a b Weiner, Natalie (April 12, 2016). "We Belong Together: Mariah Carey's Collaborators Share Untold Stories Behind 8 Classics". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 9, 2023.

- ^ a b Murphy, Keith (November 5, 2010). "Full Clip: Bone Thugs-n-Harmony Break Down Their Entire Catalogue". Vibe. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022.

- ProQuest 220165879.

- ^ Carey, Mariah (January 24, 2017). "Mariah Carey – On the Record – Fuse" (Interview). Interviewed by Touré. Fuse. Event occurs at 8:54–9:02. Archived from the original on May 16, 2023 – via YouTube.

- ProQuest 408739343.

- ^ a b Graham, Charne (September 24, 2016). "Mariah Carey's 9 Best Break-Up Songs". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022.

- ^ Newspapers.com.

- NewspaperArchive.

- ^ a b Juzwiak, Rich (September 18, 2003). "Review: Mariah Carey, Butterfly". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022.

- ^ Newspapers.com.

- ^ Newspapers.com.

- ^ Thigpen, David (September 15, 1997). "Music: Butterflies Are Free". Time. Archived from the original on November 11, 2023.

- ^ ProQuest 188045239.

- ^ a b Harrington, Richard (September 14, 1997). "Divorce and the Divas". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Preezy (September 16, 2017). "20 Years Later: Mariah Carey's Butterfly Tracklist, Ranked". Vibe. Archived from the original on November 25, 2022.

- ^ Newspapers.com.

- ^ Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Pareles, Jon (September 21, 1997). "A New Gentleness from a Pop Diva". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022.

- ^ Weheliye 2023, p. 189

- ^ Easlea, Daryl (September 21, 2011). "Mariah Carey Butterfly Review". BBC Music. Archived from the original on September 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Macpherson, Alex (June 22, 2020). "Mariah Carey: Where to Start in Her Back Catalogue". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Werthman, Christine; et al. (October 5, 2020). "The 100 Greatest Mariah Carey Songs: Staff Picks". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Cinquemani, Sal; et al. (May 15, 2020). "Every Mariah Carey Album Ranked". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on November 8, 2023.

- ^ Weheliye 2023, p. 190

- Newspapers.com.

- Sony Music Japan. Archivedfrom the original on October 6, 2022.

- ProQuest 408699285.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Shapiro 2001, p. 156

- ^ a b c d "Mariah Carey Chart History (R&B/Hip-Hop Airplay)". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022.

- ^ Newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 1505960625.

- ^ Jones, Stephen (November 22, 1997). "Mariah Carey: Moving On from the Ballads". Music Week. p. 30.

- ProQuest 1505960408.

- ^ Smith, Danyel (November 1998). "Higher and Higher". Vibe. p. 96 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ ProQuest 1506009300.

- ^ ProQuest 1506023445.

- ^ "マイ・オール" [My All] (in Japanese). Oricon. Archived from the original on October 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Mariah Carey feat. Bone Thugs-n-Harmony – 'Breakdown'". Hung Medien. Archived from the original on November 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Mariah Carey feat. Bone Thugs-n-Harmony – 'Breakdown'". Hung Medien. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022.

- ProQuest 1506038454.

- ^ The Collection (12-inch vinyl liner notes). Ruthless Records. 1998. 492857 1.

- ^ The Remixes (CD liner notes). Columbia Records. 2003. COL 510754 2.

- ^ "'Breakdown' EP" (in Japanese). Mora. Archived from the original on November 8, 2023.

- ^ Shaffer, Claire (August 19, 2020). "Mariah Carey Announces The Rarities Collection of B-Sides, Unreleased Tracks". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 16, 2023.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Nickson 1998, p. 168

- ^ a b c Weber, Lindsey; Dobbins, Amanada (May 28, 2014). "These Are Mariah Carey's 25 Best Singles". Vulture. Archived from the original on November 8, 2023.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- Newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 260585263.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Newspapers.com.

- ^ Camp, Alexa (April 1, 2005). "Behind the Caterwaul: A Mariah Carey Retrospective". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on February 25, 2023.

- ^ Kot, Greg (September 19, 1997). "Mariah Carey – Butterfly (Columbia)". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 31, 2022.

- ^ Browne, David (September 19, 1997). "Butterfly". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022.

- ^ Myers, Owen; et al. (September 28, 2022). "The 150 Best Albums of the 1990s". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on November 27, 2023.

- ^ Sanneh, Kelefa (October 20, 2003). "Disco, Alive and Dancing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022.

- ^ Cleveland.com. Archivedfrom the original on October 27, 2022.

- ProQuest 208071682.

- Newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 326737639.

- ^ Promis, Jose F. "'My All' Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on February 24, 2023.

- ^ ProQuest 1017322012.

- ^ a b "Mariah Carey Chart History (Rhythmic Airplay)". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022.

- ProQuest 1506059406.

- ^ a b "Mariah Carey Chart History (Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs)". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 22, 2022.

- ProQuest 1506024492.

- ProQuest 1506023377.

- ^ a b "Mariah Carey Chart History (Radio Songs)". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 22, 2022.

- ^ a b "Gold & Platinum – 'Breakdown'". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on March 27, 2022.

- ^ "RIAA and GR&F Certification Audit Requirements – RIAA Digital Single Award" (PDF). Recording Industry Association of America. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Scapolo 2007

- ProQuest 2092379531.

- ^ a b "Mariah Carey Songs and Albums – Full Official Chart History". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on October 31, 2022.

- ^ a b Shapiro 2001, p. 158

- ^ S2CID 35432829.

- ^ a b c d Hapsis, Emmanuel (August 12, 2015). "All 64 Mariah Carey Music Videos, Ranked from Worst to Best". KQED. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022.

- ^ Krishnamurthy, Sowmya (May 13, 2013). "10 Mariah Carey Collabos That Will Never Get Old". Vibe. Archived from the original on November 24, 2022.

- ^ a b DeCaro, Frank (March 15, 1998). "Ever So Lively, Even If Gone". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022.

- Newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 1505992019.

- ProQuest 1506050640.

- ^ "Mariah Carey Discography". MTV. Archived from the original on October 3, 2001.

- Columbia Music Video. 1998. 38V 78446.

- ^ "Mariah Carey Around the World". MTV. Archived from the original on May 26, 2002.

- Newspapers.com.

- ^ Vineyard, Jennifer (August 7, 2006). "Mariah Carey Tour Kickoff: The Voice Outshines Costume Changes, Video Clips". MTV News. Archived from the original on December 8, 2023.

- ^ Chan, Andrew (October 6, 2020). "Mariah Carey's Rarities Illuminate Pop Music's Evolution". NPR. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022.

- ^ Juzwiak, Rich (September 18, 2003). "Review: Mariah Carey, Butterfly". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022.

- Complex. Archivedfrom the original on March 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Betancourt, Bianca (September 15, 2022). "With Butterfly, Mariah Carey Became the Blueprint". Harper's Bazaar. Archived from the original on November 6, 2022.

- ProQuest 2771598742.

- ^ Welteroth 2019, p. 200

- ^ Weheliye 2023, p. 58

- ^ Chan 2023, p. 78

- ^ Reyes, Jon (n.d.). "Mariah Carey Singles That Deserved to Be No. 1 (But Didn't Get There)". BET. slide 30. Archived from the original on November 27, 2022.

- Gold Derby. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ProQuest 227261830.

- ^ Scarano, Ross; et al. (April 25, 2019). "Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Mariah Carey, 2019 BBMA Icon". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 12, 2023.

- Complex. Archivedfrom the original on November 21, 2022.

- ^ Jones, Daisy (April 28, 2015). "Mariah Carey's Greatest Hip Hop Collabs". Dazed. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023.

- ^ Thorpe, Isha (April 10, 2019). "11 of Stevie J's Most Classic Beats". Revolt. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022.

- Top 40 Airplay Monitor. March 13, 1998. p. 20.

- ^ ProQuest 1017326989.

- ProQuest 1529171323.

- Airplay Monitor. December 25, 1998. p. 46.

Books

|

|