Brewing

Brewing is the production of

The basic ingredients of beer are water and a

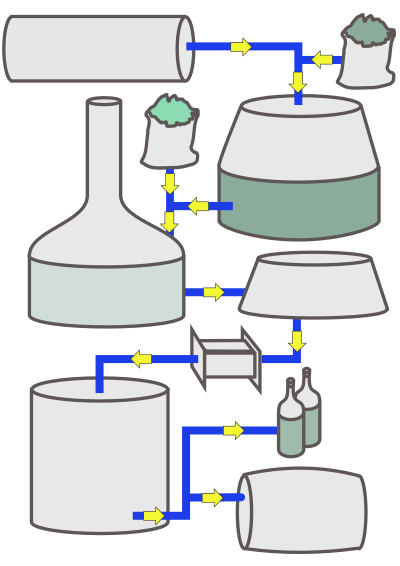

Steps in the brewing process include malting, milling, mashing, lautering, boiling, fermenting, conditioning, filtering, and packaging. There are three main fermentation methods: warm, cool and spontaneous. Fermentation may take place in an open or closed fermenting vessel; a secondary fermentation may also occur in the cask or bottle. There are several additional brewing methods, such as Burtonisation, double dropping, and Yorkshire Square, as well as post-fermentation treatment such as filtering, and barrel-ageing.

History

Brewing has taken place since around the 6th millennium BC, and archaeological evidence suggests emerging civilizations including China,[4] ancient Egypt, and Mesopotamia brewed beer. Descriptions of various beer recipes can be found in cuneiform (the oldest known writing) from ancient Mesopotamia.[3][11][12] In Mesopotamia the brewer's craft was the only profession which derived social sanction and divine protection from female deities/goddesses, specifically: Ninkasi, who covered the production of beer, Siris, who was used in a metonymic way to refer to beer, and Siduri, who covered the enjoyment of beer.[5] In pre-industrial times, and in developing countries, women are frequently the main brewers.[13][14]

As almost any cereal containing certain sugars can undergo

Ale produced before the

Ingredients

The basic ingredients of beer are water; a starch source, such as

- Water

Beer is composed mostly of water. Regions have water with different mineral components; as a result, different regions were originally better suited to making certain types of beer, thus giving them a regional character.

- Starch source

The starch source in a beer provides the fermentable material and is a key determinant of the strength and flavour of the beer. The most common starch source used in beer is malted grain. Grain is malted by soaking it in water, allowing it to begin germination, and then drying the partially germinated grain in a kiln. Malting grain produces enzymes that will allow conversion from starches in the grain into fermentable sugars during the mash process.[28] Different roasting times and temperatures are used to produce different colours of malt from the same grain. Darker malts will produce darker beers.[29]

Nearly all beer includes barley malt as the majority of the starch. This is because of its fibrous husk, which is important not only in the sparging stage of brewing (in which water is washed over the mashed barley grains to form the wort) but also as a rich source of amylase, a digestive enzyme that facilitates conversion of starch into sugars. Other malted and unmalted grains (including wheat, rice, oats, and rye, and, less frequently, maize (corn) and sorghum) may be used. In recent years, a few brewers have produced gluten-free beer made with sorghum with no barley malt for people who cannot digest gluten-containing grains like wheat, barley, and rye.[30]

- Hops

Hops are the female flower clusters or seed cones of the hop vine

Hops contain several characteristics that brewers desire in beer: they contribute a bitterness that balances the sweetness of the malt; they provide floral, citrus, and herbal aromas and flavours; they have an

- Yeast

Yeast is the microorganism that is responsible for fermentation in beer. Yeast metabolises the sugars extracted from grains, which produces alcohol and carbon dioxide, and thereby turns wort into beer. In addition to fermenting the beer, yeast influences the character and flavour.[45] The dominant types of yeast used to make beer are Saccharomyces cerevisiae, known as ale yeast, and Saccharomyces pastorianus, known as lager yeast; Brettanomyces ferments lambics,[46] and Torulaspora delbrueckii ferments Bavarian weissbier.[47] Before the role of yeast in fermentation was understood, fermentation involved wild or airborne yeasts, and a few styles such as lambics still use this method today. Emil Christian Hansen, a Danish biochemist employed by the Carlsberg Laboratory, developed pure yeast cultures which were introduced into the Carlsberg brewery in 1883,[48] and pure yeast strains are now the main fermenting source used worldwide.[49]

- Clarifying agent

Some brewers add one or more clarifying agents to beer, which typically precipitate (collect as a solid) out of the beer along with protein solids and are found only in trace amounts in the finished product. This process makes the beer appear bright and clean, rather than the cloudy appearance of ethnic and older styles of beer such as wheat beers.[50]

Examples of clarifying agents include isinglass, obtained from swim bladders of fish; Irish moss, a seaweed; kappa carrageenan, from the seaweed kappaphycus; polyclar (a commercial brand of clarifier); and gelatin.[51] If a beer is marked "suitable for Vegans", it was generally clarified either with seaweed or with artificial agents,[52] although the "Fast Cask" method invented by Marston's in 2009 may provide another method.[53]

Brewing process

There are several steps in the brewing process, which may include malting, mashing, lautering, boiling, fermenting, conditioning, filtering, and packaging.[54] The brewing equipment needed to make beer has grown more sophisticated over time, and now covers most aspects of the brewing process.[55][56]

Malting is the process where barley grain is made ready for brewing.[57] Malting is broken down into three steps in order to help to release the starches in the barley.[58] First, during steeping, the grain is added to a vat with water and allowed to soak for approximately 40 hours.[59] During germination, the grain is spread out on the floor of the germination room for around 5 days.[59] The final part of malting is kilning when the malt goes through a very high temperature drying in a kiln; with gradual temperature increase over several hours.[60] When kilning is complete, the grains are now termed malt, and they will be milled or crushed to break apart the kernels and expose the cotyledon, which contains the majority of the carbohydrates and sugars; this makes it easier to extract the sugars during mashing.[61]

The wort is moved into a large tank known as a "copper" or

After the whirlpool, the wort is drawn away from the compacted hop trub, and rapidly cooled via a

Mashing

Mashing is the process of combining a mix of milled grain (typically

Mashing usually takes 1 to 2 hours, and during this time the various temperature rests activate different enzymes depending upon the type of malt being used, its modification level, and the intention of the brewer. The activity of these enzymes convert the starches of the grains to

Lautering

Lautering is the separation of the wort (the liquid containing the sugar extracted during mashing) from the grains.[78] This is done either in a mash tun outfitted with a false bottom, in a lauter tun, or in a mash filter. Most separation processes have two stages: first wort run-off, during which the extract is separated in an undiluted state from the spent grains, and sparging, in which extract which remains with the grains is rinsed off with hot water. The lauter tun is a tank with holes in the bottom small enough to hold back the large bits of grist and hulls (the ground or milled cereal).[79] The bed of grist that settles on it is the actual filter. Some lauter tuns have provision for rotating rakes or knives to cut into the bed of grist to maintain good flow. The knives can be turned so they push the grain, a feature used to drive the spent grain out of the vessel.[80] The mash filter is a plate-and-frame filter. The empty frames contain the mash, including the spent grains, and have a capacity of around one hectoliter. The plates contain a support structure for the filter cloth. The plates, frames, and filter cloths are arranged in a carrier frame like so: frame, cloth, plate, cloth, with plates at each end of the structure. Newer mash filters have bladders that can press the liquid out of the grains between spargings. The grain does not act like a filtration medium in a mash filter.[81]

Boiling

After mashing, the beer wort is boiled with hops (and other flavourings if used) in a large tank known as a "copper" or brew kettle – though historically the mash vessel was used and is still in some small breweries.[82] The boiling process is where chemical reactions take place,[64] including sterilization of the wort to remove unwanted bacteria, releasing of hop flavours, bitterness and aroma compounds through isomerization, stopping of enzymatic processes, precipitation of proteins, and concentration of the wort.[83][84] Finally, the vapours produced during the boil volatilise off-flavours, including dimethyl sulfide precursors.[84] The boil is conducted so that it is even and intense – a continuous "rolling boil".[84] The boil on average lasts between 45 and 90 minutes, depending on its intensity, the hop addition schedule, and volume of water the brewer expects to evaporate.[85] At the end of the boil, solid particles in the hopped wort are separated out, usually in a vessel called a "whirlpool".[65]

Brew kettle or copper

Copper is the traditional material for the boiling vessel for two main reasons: firstly because copper transfers heat quickly and evenly; secondly because the bubbles produced during boiling, which could act as an insulator against the heat, do not cling to the surface of copper, so the wort is heated in a consistent manner.[86] The simplest boil kettles are direct-fired, with a burner underneath. These can produce a vigorous and favourable boil, but are also apt to scorch the wort where the flame touches the kettle, causing caramelisation and making cleanup difficult. Most breweries use a steam-fired kettle, which uses steam jackets in the kettle to boil the wort.[84] Breweries usually have a boiling unit either inside or outside of the kettle, usually a tall, thin cylinder with vertical tubes, called a calandria, through which wort is pumped.[87]

Whirlpool

At the end of the boil, solid particles in the hopped wort are separated out, usually in a vessel called a "whirlpool" or "settling tank".[65][88] The whirlpool was devised by Henry Ranulph Hudston while working for the Molson Brewery in 1960 to utilise the so-called tea leaf paradox to force the denser solids known as "trub" (coagulated proteins, vegetable matter from hops) into a cone in the centre of the whirlpool tank.[89][90][91] Whirlpool systems vary: smaller breweries tend to use the brew kettle, larger breweries use a separate tank,[88] and design will differ, with tank floors either flat, sloped, conical or with a cup in the centre.[92] The principle in all is that by swirling the wort the centripetal force will push the trub into a cone at the centre of the bottom of the tank, where it can be easily removed.[88]

Hopback

A hopback is a traditional additional chamber that acts as a sieve or filter by using whole hops to clear debris (or "trub") from the unfermented (or "green") wort,[93] as the whirlpool does, and also to increase hop aroma in the finished beer.[94][95] It is a chamber between the brewing kettle and wort chiller. Hops are added to the chamber, the hot wort from the kettle is run through it, and then immediately cooled in the wort chiller before entering the fermentation chamber. Hopbacks utilizing a sealed chamber facilitate maximum retention of volatile hop aroma compounds that would normally be driven off when the hops contact the hot wort.[96] While a hopback has a similar filtering effect as a whirlpool, it operates differently: a whirlpool uses centrifugal forces, a hopback uses a layer of whole hops to act as a filter bed. Furthermore, while a whirlpool is useful only for the removal of pelleted hops (as flowers do not tend to separate as easily), in general hopbacks are used only for the removal of whole flower hops (as the particles left by pellets tend to make it through the hopback).[97] The hopback has mainly been substituted in modern breweries by the whirlpool.[98]

Wort cooling

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2019) |

After the whirlpool, the wort must be brought down to fermentation temperatures 20–26 °C (68–79 °F)

While boiling, it is useful to recover some of the energy used to boil the wort. On its way out of the brewery, the steam created during the boil is passed over a coil through which unheated water flows. By adjusting the rate of flow, the output temperature of the water can be controlled. This is also often done using a plate heat exchanger. The water is then stored for later use in the next mash, in equipment cleaning, or wherever necessary.[99] Another common method of energy recovery takes place during the wort cooling. When cold water is used to cool the wort in a heat exchanger, the water is significantly warmed. In an efficient brewery, cold water is passed through the heat exchanger at a rate set to maximize the water's temperature upon exiting. This now-hot water is then stored in a hot water tank.[99]

Fermenting

Most breweries today use cylindroconical vessels, or CCVs, which have a conical bottom and a cylindrical top. The cone's angle is typically around 60°, an angle that will allow the yeast to flow towards the cone's apex, but is not so steep as to take up too much vertical space. CCVs can handle both fermenting and conditioning in the same tank. At the end of fermentation, the yeast and other solids which have fallen to the cone's apex can be simply flushed out of a port at the apex. Open fermentation vessels are also used, often for show in brewpubs, and in Europe in wheat beer fermentation. These vessels have no tops, which makes harvesting top-fermenting yeasts very easy. The open tops of the vessels make the risk of infection greater, but with proper cleaning procedures and careful protocol about who enters fermentation chambers, the risk can be well controlled. Fermentation tanks are typically made of stainless steel. If they are simple cylindrical tanks with beveled ends, they are arranged vertically, as opposed to conditioning tanks which are usually laid out horizontally. Only a very few breweries still use wooden vats for fermentation as wood is difficult to keep clean and infection-free and must be repitched more or less yearly.[100][101][102]

Fermentation methods

There are three main fermentation methods,

Brewing yeasts are traditionally classed as "top-cropping" (or "top-fermenting") and "bottom-cropping" (or "bottom-fermenting"); the yeasts classed as top-fermenting are generally used in warm fermentations, where they ferment quickly, and the yeasts classed as bottom-fermenting are used in cooler fermentations where they ferment more slowly.[104] Yeast were termed top or bottom cropping, because the yeast was collected from the top or bottom of the fermenting wort to be reused for the next brew.[105] This terminology is somewhat inappropriate in the modern era; after the widespread application of brewing mycology it was discovered that the two separate collecting methods involved two different yeast species that favoured different temperature regimes, namely Saccharomyces cerevisiae in top-cropping at warmer temperatures and Saccharomyces pastorianus in bottom-cropping at cooler temperatures.[106] As brewing methods changed in the 20th century, cylindro-conical fermenting vessels became the norm and the collection of yeast for both Saccharomyces species is done from the bottom of the fermenter. Thus the method of collection no longer implies a species association. There are a few remaining breweries who collect yeast in the top-cropping method, such as Samuel Smiths brewery in Yorkshire, Marstons in Staffordshire and several German hefeweizen producers.[105]

For both types, yeast is fully distributed through the beer while it is fermenting, and both equally flocculate (clump together and precipitate to the bottom of the vessel) when fermentation is finished. By no means do all top-cropping yeasts demonstrate this behaviour, but it features strongly in many English yeasts that may also exhibit chain forming (the failure of budded cells to break from the mother cell), which is in the technical sense different from true flocculation. The most common top-cropping brewer's yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is the same species as the common baking yeast. However, baking and brewing yeasts typically belong to different strains, cultivated to favour different characteristics: baking yeast strains are more aggressive, in order to carbonate dough in the shortest amount of time; brewing yeast strains act slower, but tend to tolerate higher alcohol concentrations (normally 12–15% abv is the maximum, though under special treatment some ethanol-tolerant strains can be coaxed up to around 20%).[107] Modern quantitative genomics has revealed the complexity of Saccharomyces species to the extent that yeasts involved in beer and wine production commonly involve hybrids of so-called pure species. As such, the yeasts involved in what has been typically called top-cropping or top-fermenting ale may be both Saccharomyces cerevisiae and complex hybrids of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces kudriavzevii. Three notable ales, Chimay, Orval and Westmalle, are fermented with these hybrid strains, which are identical to wine yeasts from Switzerland.[108]

Warm fermentation

In general, yeasts such as

Cool fermentation

When a beer has been brewed using a cool fermentation of around 10 °C (50 °F), compared to typical warm fermentation temperatures of 18 °C (64 °F),[114][115] then stored (or lagered) for typically several weeks (or months) at temperatures close to freezing point, it is termed a "lager".[116] During the lagering or storage phase several flavour components developed during fermentation dissipate, resulting in a "cleaner" flavour.[117][118] Though it is the slow, cool fermentation and cold conditioning (or lagering) that defines the character of lager,[119] the main technical difference is with the yeast generally used, which is Saccharomyces pastorianus.[120] Technical differences include the ability of lager yeast to metabolize melibiose,[121] and the tendency to settle at the bottom of the fermenter (though ale yeasts can also become bottom settling by selection);[121] though these technical differences are not considered by scientists to be influential in the character or flavour of the finished beer, brewers feel otherwise - sometimes cultivating their own yeast strains which may suit their brewing equipment or for a particular purpose, such as brewing beers with a high abv.[122][123][124][125]

Brewers in Bavaria had for centuries been selecting cold-fermenting yeasts by storing ("lagern") their beers in cold alpine caves. The process of natural selection meant that the wild yeasts that were most cold tolerant would be the ones that would remain actively fermenting in the beer that was stored in the caves. A sample of these Bavarian yeasts was sent from the Spaten brewery in Munich to the Carlsberg brewery in Copenhagen in 1845 who began brewing with it. In 1883 Emile Hansen completed a study on pure yeast culture isolation and the pure strain obtained from Spaten went into industrial production in 1884 as Carlsberg yeast No 1. Another specialized pure yeast production plant was installed at the Heineken Brewery in Rotterdam the following year and together they began the supply of pure cultured yeast to brewers across Europe.[126][127] This yeast strain was originally classified as Saccharomyces carlsbergensis, a now defunct species name which has been superseded by the currently accepted taxonomic classification Saccharomyces pastorianus.[128]

Spontaneous fermentation

Lambic beers are historically brewed in Brussels and the nearby Pajottenland region of Belgium without any yeast inoculation.[129][130] The wort is cooled in open vats (called "coolships"), where the yeasts and microbiota present in the brewery (such as Brettanomyces)[131] are allowed to settle to create a spontaneous fermentation,[132] and are then conditioned or matured in oak barrels for typically one to three years.[133]

Conditioning

After an initial or primary fermentation, beer is conditioned, matured or aged,[134] in one of several ways,[135] which can take from 2 to 4 weeks, several months, or several years, depending on the brewer's intention for the beer. The beer is usually transferred into a second container, so that it is no longer exposed to the dead yeast and other debris (also known as "trub") that have settled to the bottom of the primary fermenter. This prevents the formation of unwanted flavours and harmful compounds such as acetaldehyde.[136]

- Kräusening

Kräusening (pronounced KROY-zen-ing[137]) is a conditioning method in which fermenting wort is added to the finished beer.[138] The active yeast will restart fermentation in the finished beer, and so introduce fresh carbon dioxide; the conditioning tank will be then sealed so that the carbon dioxide is dissolved into the beer producing a lively "condition" or level of carbonation.[138] The kräusening method may also be used to condition bottled beer.[138]

- Lagering

Lagers are stored at cellar temperature or below for 1–6 months while still on the yeast.[139] The process of storing, or conditioning, or maturing, or aging a beer at a low temperature for a long period is called "lagering", and while it is associated with lagers, the process may also be done with ales, with the same result – that of cleaning up various chemicals, acids and compounds.[140]

- Secondary fermentation

During secondary fermentation, most of the remaining yeast will settle to the bottom of the second fermenter, yielding a less hazy product.[141]

- Bottle fermentation

Some beers undergo an additional fermentation in the bottle giving natural carbonation.[142] This may be a second and/or third fermentation. They are bottled with a viable yeast population in suspension. If there is no residual fermentable sugar left, sugar or wort or both may be added in a process known as priming. The resulting fermentation generates CO2 that is trapped in the bottle, remaining in solution and providing natural carbonation. Bottle-conditioned beers may be either filled unfiltered direct from the fermentation or conditioning tank, or filtered and then reseeded with yeast.[143]

- Cask conditioning

Cask ale (or cask-conditioned beer) is

- Barrel-ageing

Barrel-ageing (

Filtering

Filtering stabilises the flavour of beer, holding it at a point acceptable to the brewer, and preventing further development from the yeast, which under poor conditions can release negative components and flavours.

There are several forms of filters; they may be in the form of sheets or "candles", or they may be a fine powder such as diatomaceous earth (also called kieselguhr),[152] which is added to the beer to form a filtration bed which allows liquid to pass, but holds onto suspended particles such as yeast.[153] Filters range from rough filters that remove much of the yeast and any solids (e.g., hops, grain particles) left in the beer,[154] to filters tight enough to strain colour and body from the beer.[citation needed] Filtration ratings are divided into rough, fine, and sterile.[citation needed] Rough filtration leaves some cloudiness in the beer, but it is noticeably clearer than unfiltered beer.[citation needed] Fine filtration removes almost all cloudiness.[citation needed] Sterile filtration removes almost all microorganisms.[citation needed]

- Sheet (pad) filters

These filters use sheets that allow only particles smaller than a given size to pass through. The sheets are placed into a filtering frame, sanitized (with boiling water, for example) and then used to filter the beer. The sheets can be flushed if the filter becomes blocked. The sheets are usually disposable and are replaced between filtration sessions. Often the sheets contain powdered filtration media to aid in filtration.

Pre-made filters have two sides. One with loose holes, and the other with tight holes. Flow goes from the side with loose holes to the side with the tight holes, with the intent that large particles get stuck in the large holes while leaving enough room around the particles and filter medium for smaller particles to go through and get stuck in tighter holes.

Sheets are sold in nominal ratings, and typically 90% of particles larger than the nominal rating are caught by the sheet.

- Kieselguhr filters

Filters that use a powder medium are considerably more complicated to operate, but can filter much more beer before regeneration. Common media include diatomaceous earth and perlite.

By-products

Brewing by-products are "spent grain" and the sediment (or "dregs") from the filtration process which may be dried and resold as "brewers dried yeast" for poultry feed,[155] or made into yeast extract which is used in brands such as Vegemite and Marmite.[156] The process of turning the yeast sediment into edible yeast extract was discovered by German scientist Justus von Liebig.[157]

Brewing industry

The brewing industry is a global business, consisting of several dominant

Brewing at home is subject to regulation and prohibition in many countries. Restrictions on homebrewing were lifted in the UK in 1963,[171] Australia followed suit in 1972,[172] and the US in 1978, though individual states were allowed to pass their own laws limiting production.[173]

References

- ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 23 December 2019.

- ISBN 9781118598122. Archivedfrom the original on 21 May 2016.

- ^ OCLC 71834130.

- ^ PMID 15590771.

- ^ a b Louis F Hartman & A. L. Oppenheim (December 1950). "On Beer and Brewing Techniques in Ancient Mesopotamia". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 10 (Supplement).

- ^ a b alabev.com Archived 23 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Ingredients of Beer. Retrieved 29 September 2008

- ^ a b Michael Jackson (1 October 1997). "A good beer is a thorny problem down Mexico way". BeerHunter.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ ISBN 0-9675212-0-3. Retrieved 29 September 2008

- ^ ISBN 9780199912100. Archivedfrom the original on 26 December 2019.

- ^ "World's oldest beer receipt? – Free Online Library". thefreelibrary.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- from the original on 5 December 2007. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Thomas W. Young. "Beer - Alcoholic Beverage". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2007. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-292-72104-3. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ Ray Anderson (2005). "The Transformation of Brewing: An Overview of Three Centuries of Science and Practice". Brewery History. 121. Brewery History Society: 5–24. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0507-102. Archived from the originalon 16 October 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- ^ Horst Dornbusch (27 August 2006). "Beer: The Midwife of Civilization". Assyrian International News Agency. Archived from the original on 27 March 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- ^ Roger Protz (2004). "The Complete Guide to World Beer". Archived from the original on 25 April 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

When people of the ancient world realised they could make bread and beer from grain, they stopped roaming and settled down to cultivate cereals in recognisable communities.

- University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Archivedfrom the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ^ [1] Archived 12 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine Prehistoric brewing: the true story, 22 October 2001, Archaeo News. Retrieved 13 September 2008

- ^ [2] Archived 9 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine Dreher Breweries, Beer-history

- ISBN 978-0-7553-1165-1.

- ^ a b "Industry Browser — Consumer Non-Cyclical — Beverages (Alcoholic) – Company List". Yahoo! Finance. Archived from the original on 2 October 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ^ "Beer: Global Industry Guide". Research and Markets. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ISBN 9781118052440. Archivedfrom the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Geology and Beer". Geotimes. August 2004. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ^ "Water For Brewing". Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ [3] Archived 19 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine Michael Jackson, BeerHunter, 19 October 1991, Brewing a good glass of water. Retrieved 13 September 2008

- ^ Wikisource 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Brewing/Chemistry. Retrieved 29 September 2008

- ^ Farm-direct Archived 14 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine Oz, Barley Malt, 6 February 2002. Retrieved 29 September 2008

- ^ Carolyn Smagalski (2006). "CAMRA & The First International Gluten Free Beer Festival". Carolyn Smagalski, Bella Online. Archived from the original on 2 October 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ "University of Minnesota Libraries: The Transfer of Knowledge. Hops-Humulus lupulus". Lib.umn.edu. 13 May 2008. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ISBN 9780470943540. Archivedfrom the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ISBN 978-0812203745. Archivedfrom the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-7553-1165-1.

- ISBN 9780854046300. Archivedfrom the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ISBN 9781603583640. Archivedfrom the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ "Heatherale.co.uk". Fraoch.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "La Brasserie Lancelot est située au coeur de la Bretagne, dans des bâtiments rénovés de l'ancienne mine d'Or du Roc St-André, construits au XIXe siècle sur des vestiges néolithiques". Brasserie-lancelot.com. Archived from the original on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ISBN 9789380578019. Archivedfrom the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ISBN 9781579580780.

- ISBN 9781118598122. Archivedfrom the original on 3 June 2016.

- ISBN 9781107605954. Archivedfrom the original on 1 May 2016.

- ^ Blanco Carlos A.; Rojas Antonio; Caballero Pedro A.; Ronda Felicidad; Gomez Manuel; Caballero. "A better control of beer properties by predicting acidity of hop iso-α-acids". Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- ISBN 978-0-471-12350-7.

- ^ S. Ostergaard; L. Olsson; J. Nielsen. "Metabolic Engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000 64". pp. 34–50. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ Ian Spencer Hornsey (25 November 1999). Brewing. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 221–222.

- ^ Web.mst.edu Archived 9 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine David Horwitz, Torulaspora delbrueckii. Retrieved 30 September 2008

- ISBN 9780854046300. Archivedfrom the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ISBN 9780306472749. Archivedfrom the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ "Michael Jackson's Beer Hunter – A pint of cloudy, please". Beerhunter.com. Archived from the original on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ EFSA Archived 3 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies, 23 August 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2008

- ^ Food.gov.uk Archived 2 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine Draft Guidance on the Use of the Terms 'Vegetarian' and 'Vegan' in Food Labelling: Consultation Responses pp71, 5 October 2005. Retrieved 29 September 2008

- ^ Roger Protz (15 March 2010). "Fast Cask". Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ISBN 9780849398490. Archivedfrom the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ISBN 9781118120309.

- ISBN 9780849390357.

- ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ISBN 9781442204119. Archivedfrom the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ISBN 9780306472749. Archivedfrom the original on 25 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Ale University – Brewing Process". Merchant du Vin. 2009. Archived from the original on 3 November 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ^ John Palmer. "Single Temperature Infusion". How to Brew. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-9675212-3-7.

- ^ a b c "History of Beer". Foster's Group. July 2005. Archived from the original on 16 February 2006.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85404-630-0.

- ISBN 9780199742707.

- ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ISBN 9780306472749. Archivedfrom the original on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ISBN 9781616084639. Archivedfrom the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ISBN 9780313380488. Archivedfrom the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ The Saturday Magazine (September 1835). "The Useful Arts No. X". The Saturday Magazine: 120. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-8493-8980-1.

- ISBN 978-1-57958-078-0.

- ^ a b "Abdijbieren. Geestrijk erfgoed" by Jef Van den Steen

- ^ "Bier brouwen". 19 April 2008. Archived from the original on 19 April 2008. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ "What is mashing?". Realbeer.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ISBN 3-921690-49-8.

- ISBN 978-0-8138-1942-6.

- ^ "Lauter Tun Use in Brewing Beer". beer-brewing.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2010. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-9675212-3-7.

- ^ "Mash Filter Use in Brewing Beer". beer-brewing.com. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ISBN 978-0812203745. Archivedfrom the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ISBN 9780801895692. Archivedfrom the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ISBN 9780387330105. Archivedfrom the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ISBN 9780306472749. Archivedfrom the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 2 May 2016.

- ^ ISBN 9780199912100. Archivedfrom the original on 27 May 2016.

- ^ W. Reed (1969). "The Whirlpool". International Brewers' Journal. 105 (2): 41.

- ^ Darrell Little (20 March 2013). "Teacups, Albert Einstein, and Henry Hudston". mooseheadbeeracademy.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ISBN 9780199756360. Archivedfrom the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ISBN 9780834216846. Archivedfrom the original on 6 May 2016.

- ISBN 9781741968132. Archivedfrom the original on 19 December 2019.

- ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 4 June 2016.

- ISBN 9781849736022. Archivedfrom the original on 9 May 2016.

- ISBN 9780719030321. Archivedfrom the original on 17 June 2016.

- ISBN 9780834216846. Archivedfrom the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ISBN 9780199912100. Archivedfrom the original on 14 May 2016.

- ^ ISBN 3-921690-49-8.

- ^ ISBN 9780199912100.

- ^ ISBN 9781118598122. Archivedfrom the original on 8 May 2016.

- ^ ISBN 9781118685341. Archivedfrom the original on 28 May 2016.

- ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 2 December 2019.

- ISBN 9780824726577. Archivedfrom the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ a b Tom Colicchio (2011). The Oxford Companion to Beer. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Emil Christian Hansen (1896). Practical studies in fermentation: being contributions to the life history of micro-organisms. E. & FN Spon. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ISBN 9780199912100. Archivedfrom the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ González, Sara S., Eladio Barrio, and Amparo Querol. "Molecular characterization of new natural hybrids of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and S. kudriavzevii in brewing". Applied and Environmental Microbiology 74.8 (2008): 2314–2320.

- ISBN 0-306-47706-8.

- ISBN 0-937381-84-5

- ISBN 0-306-47706-8.

- ISBN 978-0-632-05987-4.

- ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ISBN 9781938469060. Archivedfrom the original on 22 December 2019.

- ISBN 9781938469251.

- ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ISBN 9780080453828. Archivedfrom the original on 21 December 2019.

- ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ISBN 9781938469237. Archivedfrom the original on 22 December 2019.

- ISBN 9780080920498.

- ^ ISBN 9781845698485. Archivedfrom the original on 23 December 2019.

- ^ Briggs, Dennis Edward; et al. (2004). Brewing: science and practice. Elsevier. p. 123.

- ISBN 9780470174487. Archivedfrom the original on 22 December 2019.

- ^ Dan Rose. "Harveys let us in on some brewing secrets". businessinbrighton.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 28 December 2019.

- ^ Meussdoerffer, Franz G. "A comprehensive history of beer brewing". Handbook of brewing: processes, technology, markets (2009): 1–42.

- ^ Boulton, Christopher, and David Quain. Brewing yeast and fermentation. John Wiley & Sons, 2008.

- ISBN 9783319179155. Archivedfrom the original on 21 December 2019.

- ISBN 9780199912100. Archivedfrom the original on 16 May 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ISBN 9780062042835. Archivedfrom the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ Verachtert H, Iserentant D (1995). "Properties of Belgian acid beers and their microflora. 1. The production of gueuze and related refreshing acid beers". Cerevesia. 20 (1): 37–42.

- ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 24 December 2019.

- PMID 24748344.

- ISBN 9780824726577. Archivedfrom the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ISBN 9780854045686. Archivedfrom the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ISBN 9780824726577. Archivedfrom the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ "Definition of KRAUSEN". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ISBN 0-8493-2547-1p. 5.

- ISBN 9780195367133. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ISBN 9780824726577. Archivedfrom the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ISBN 9781118598122. Archivedfrom the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ISBN 9781118598122. Archivedfrom the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ISBN 9780854045686. Archivedfrom the original on 11 June 2016.

- ISBN 9781118598122. Archivedfrom the original on 14 May 2016.

- ISBN 9780330536806. Archivedfrom the original on 23 July 2016.

- ^ "CAMRA looks to the future as its members call for positive change". CAMRA - Campaign for Real Ale. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "Craft Beer and Brewing. Single Barrel, Double Barrel? No Barrel!". Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-306-47706-5.

- ISBN 9780195367133. Archivedfrom the original on 22 December 2019.

- ^ Edward Ralph Moritz; George Harris Morris (1891). The Science of Brewing. E. & F. N. Spon. p. 405.

- ^ "Kieselguhr". sciencedirect.com.

- ISBN 9781946204776.

- ISBN 9781420015171.

- ISBN 9781845934286. Archivedfrom the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ISBN 9780199756360. Archivedfrom the original on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ISBN 9780313354755. Archivedfrom the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ISBN 9781439815212. Archivedfrom the original on 26 December 2019.

- PMID 18581454.

- ^ .

- ^ a b Heuzé V., Tran G., Sauvant D., Lebas F., 2016. Brewers grains. Feedipedia, a programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. https://www.feedipedia.org/node/74 Archived 24 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine Last updated on 17 June 2016, 16:10

- ISBN 978-1-58008-759-9.

- ISBN 9789401717502. Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2018.

- ISBN 9789812837554. Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2018.

- ^ "Storm Brewing – a Canadian brewery that grows shiitake mushrooms on spent grain". Stormbrewing.ca. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ^ Ferraz et al., Spent brewery grains for improvement of thermal insulation of ceramic bricks. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering. DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0000729

- ^ "Market Segments: Microbrewery". Brewers Association. 2012. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "Beer: Global Industry Guide". Research and Markets. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ^ "Brewer to snap up Miller for $5.6B". CNN. 30 May 2002. Archived from the original on 7 December 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- ^ "InBev Completes Acquisition of Anheuser-Busch" (PDF) (Press release). AB-InBev. 18 November 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "New Statesman – What's your poison?". newstatesman.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ "Adelaide Times Online". Archived from the original on 20 August 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

- ISBN 0-06-053105-3

- Sources

- Bamforth, Charles; Food, Fermentation and Micro-organisms, ISBN 0-632-05987-7

- Bamforth, Charles; Beer: Tap into the Art and Science of Brewing, Oxford University Press, 2009

- Boulton, Christopher; Encyclopaedia of Brewing, ISBN 978-1-4051-6744-4

- Briggs, Dennis E., et al.; Malting and Brewing Science, ISBN 0-8342-1684-1

- Ensminger, Audrey; Foods & Nutrition Encyclopedia, ISBN 0-8493-8980-1

- Esslinger, Hans Michael; Handbook of Brewing: Processes, Technology, Markets, ISBN 3-527-31674-4

- Hornsey, Ian Spencer; Brewing, ISBN 0-85404-568-6

- Hui, Yiu H.; Food Biotechnology, ISBN 0-471-18570-1

- Hui, Yiu H., and Smith, J. Scott; Food Processing: Principles and Applications, ISBN 978-0-8138-1942-6

- Andrew G.H. Lea, John Raymond Piggott, John R. Piggott ; Fermented Beverage Production, ISBN 0-306-47706-8

- McFarland, Ben; World's Best Beers, ISBN 978-1-4027-6694-7

- Oliver, Garrett (ed); The Oxford Companion to Beer, Oxford University Press, 2011

- Priest, Fergus G.; Handbook of Brewing, ISBN 0-8247-2657-X

- Rabin, Dan; Forget, Carl (1998). The Dictionary of Beer and Brewing (Print). Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn/ISBN 978-1-57958-078-0.

- Stevens, Roger, et al.; Brewing: Science and Practice, ISBN 0-8493-2547-1

- Unger, Richard W.; Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, ISBN 0-8122-3795-1