Celtic Britons

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2021) |

The Britons (

The earliest written evidence for the Britons is from

Following the

Name

In Celtic studies, 'Britons' refers to native speakers of the Brittonic languages in the ancient and medieval periods, "from the first evidence of such speech in the pre-Roman Iron Age, until the central Middle Ages".[2]

The earliest known reference to the habitants of Britain was by Pytheas, a Greek geographer who made a voyage of exploration around the British Isles between 330 and 320 BC. Although none of his own writings remain, writers during the following centuries made much reference to them. The ancient Greeks called the people of Britain the Pretanoí or Bretanoí.[2] Pliny's Natural History (77 AD) says the older name for the island was Albion,[2] and Avienius calls it insula Albionum, "island of the Albions".[7][8] The name could have reached Pytheas from the Gauls.[8] The Latin name for the Britons was Britanni.[2][9]

The

The medieval Welsh form of Latin Britanni was Brython (singular and plural).

In the

From the early 16th century, and especially after the Acts of Union 1707, the terms British and Briton could be applied to all inhabitants of the Kingdom of Great Britain, including the English, Scottish, and some Irish, or the subjects of the British Empire generally.[13]

Language

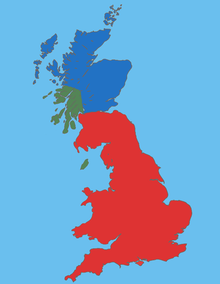

The Britons spoke an Insular Celtic language known as Common Brittonic. Brittonic was spoken throughout the island of Britain (in modern terms, England, Wales, and Scotland).[2][14] According to early medieval historical tradition, such as The Dream of Macsen Wledig, the post-Roman Celtic speakers of Armorica were colonists from Britain, resulting in the Breton language, a language related to Welsh and identical to Cornish in the early period, and is still used today. Thus, the area today is called Brittany (Br. Breizh, Fr. Bretagne, derived from Britannia).

Common Brittonic developed from the Insular branch of the

Tribal groups

Celtic Britain was made up of many territories controlled by

, is cognate with Pritenī.The following is a list of the major Brittonic tribes, in both the Latin and Brittonic languages, as well as their capitals during the Roman period.

Art

The

The carnyx, a trumpet with an animal-headed bell, was used by Celtic Britons during war and ceremony.[16][17]

History

Origins

There are competing hypotheses for when Celtic peoples, and the Celtic languages, first arrived in Britain, none of which have gained consensus. The traditional view during most of the twentieth century was that Celtic culture grew out of the central European Hallstatt culture, from which the Celts and their languages reached Britain in the second half of the first millennium BC.[18][19] More recently, John Koch and Barry Cunliffe have challenged that with their 'Celtic from the West' theory, which has the Celtic languages developing as a maritime trade language in the Atlantic Bronze Age cultural zone before it spread eastward.[20] Alternatively, Patrick Sims-Williams criticizes both of these hypotheses to propose 'Celtic from the Centre', which suggests Celtic originated in Gaul and spread during the first millennium BC, reaching Britain towards the end of this period.[21]

In 2021, a major archaeogenetics study uncovered a migration into southern Britain during the Bronze Age, over a 500-year period from 1,300 BC to 800 BC.[22] The migrants were "genetically most similar to ancient individuals from France" and had higher levels of Early European Farmers ancestry.[22] From 1000 to 875 BC, their genetic marker swiftly spread through southern Britain,[23] making up around half the ancestry of subsequent Iron Age people in this area, but not in northern Britain.[22] The "evidence suggests that rather than a violent invasion or a single migratory event, the genetic structure of the population changed through sustained contacts between mainland Britain and Europe over several centuries, such as the movement of traders, intermarriage, and small-scale movements of family groups".[23] The authors describe this as a "plausible vector for the spread of early Celtic languages into Britain".[22] There was much less migration into Britain during the subsequent Iron Age, so it is more likely that Celtic reached Britain before then.[22] Barry Cunliffe suggests that a branch of Celtic was already being spoken in Britain and that the Bronze Age migration introduced the Brittonic branch.[24]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was originally compiled by the orders of King Alfred the Great in approximately 890, starts with this sentence: "The island Britain is 800 miles long and 200 miles broad. And there are in the island five nations; English, Welsh (or British), Scottish, Pictish, and Latin. The first inhabitants were the Britons, who came from Armenia, and first peopled Britain southward" ("Armenia" is possibly a mistaken transcription of Armorica, an area in northwestern Gaul including modern Brittany).[25]

Worship of chickens and hares

Unlike most other cultures, the Britons considered the consumption of chickens and hares to be taboo, because they considered these animals to be sacred.[26][27][28] Archaeological evidence suggests that the Britons buried the bodies of dead chickens in a ritual manner, and Julius Caesar once wrote in Commentarii de Bello Gallico "The Britons consider it contrary to divine law to eat the hare, the chicken or the goose. They raise these, however, for their own amusement or pleasure".[27] The Britons started eating chickens and hares when the Roman Empire conquered Britain. After the Romans lost control of Britain in AD 410, the chicken population in Britain dramatically declined, and the Britons may have begun worshiping chickens again.[26]

Roman conquest

In 43 AD, the Roman Empire invaded Britain. The British tribes opposed the Roman legions for many decades, but by 84 AD the Romans had decisively conquered southern Britain and had pushed into Brittonic areas of what would later become northern England and southern Scotland. During the same period,

Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain

Thirty years or so after the time of the Roman departure, the Germanic-speaking Anglo-Saxons began a migration to the south-eastern coast of Britain, where they began to establish their own kingdoms, and the Gaelic-speaking Scots migrated from Dál nAraidi (modern Northern Ireland) to the west coast of Scotland and the Isle of Man.[30][31]

At the same time, Britons established themselves in what is now called

Many of the old Brittonic kingdoms began to disappear in the centuries after the Anglo-Saxon and Scottish Gaelic invasions; Parts of the regions of modern East Anglia, East Midlands, North East England, Argyll, and South East England were the first to fall to the Germanic and Gaelic Scots invasions.

The kingdom of Ceint (modern Kent) fell in 456 AD. Linnuis (which stood astride modern Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire) was subsumed as early as 500 AD and became the English Kingdom of Lindsey.

Yr Hen Ogledd (the Old North)

Some Brittonic kingdoms were able to successfully resist these incursions:

The

The

), had also all fallen by the beginning of the 11th century AD or shortly after.The Brythonic languages in these areas were eventually replaced by the Old English of the Anglo-Saxons, and Scottish Gaelic, although this was likely a gradual process in many areas.

Similarly, the Brittonic colony of Britonia in northwestern Spain appears to have disappeared soon after 900 AD.

The kingdom of

Wales, Cornwall and Brittany

The Britons also retained control of Wales and Kernow (encompassing Cornwall, parts of Devon including Dartmoor, and the Isles of Scilly) until the mid 11th century AD when Cornwall was effectively annexed by the English, with the Isles of Scilly following a few years later, although at times Cornish lords appear to have retained sporadic control into the early part of the 12th century AD.

Wales remained free from Anglo-Saxon, Gaelic Scots and Viking control, and was divided among varying Brittonic kingdoms, the foremost being

However, by the early 1100s, the Anglo-Saxons and Gaels had become the dominant cultural force in most of the formerly Brittonic ruled territory in Britain, and the language and culture of the native Britons was thereafter gradually replaced in those regions,[40] remaining only in Wales, Cornwall, the Isles of Scilly and Brittany, and for a time in parts of Cumbria, Strathclyde, and eastern Galloway.

Cornwall (Kernow, Dumnonia) had certainly been largely absorbed by England by the 1050s to early 1100s, although it retained a distinct Brittonic culture and language.[41] Britonia in Spanish Galicia seems to have disappeared by 900 AD.

Wales and Brittany remained independent for a considerable time, however, with Brittany united with

Wales, Cornwall, Brittany and the Isles of Scilly continued to retain a distinct Brittonic culture, identity and language, which they have maintained to the present day. The Welsh and Breton languages remain widely spoken, and the Cornish language, once close to extinction, has experienced a revival since the 20th century. The vast majority of place names and names of geographical features in Wales, Cornwall, the Isles of Scilly and Brittany are Brittonic, and Brittonic family and personal names remain common.

During the 19th century, many Welsh farmers migrated to Patagonia in Argentina, forming a community called Y Wladfa, which today consists of over 1,500 Welsh speakers.

In addition, a Brittonic legacy remains in England, Scotland and Galicia in Spain,.

Genetics

Schiffels et al. (2016) examined the remains of three Iron Age Britons buried ca. 100 BC.

Martiano et al. (2016) examined the remains of a female Iron Age Briton buried at

See also

- Albion

- Bretons

- British Latin

- Celtic nations

- Celtic language decline in England

- Cornish people

- Cumbric

- English people

- Fortriu

- Genetic history of the British Isles

- Gododdin

- History of the British Isles

- Kingdom of Cat

- Kingdom of Ce

- Kingdom of Strathclyde

- List of Celtic tribes

- Scottish people

- Welsh people

- Yr Hen Ogledd

References

- ^ Graham Webster. (1996). "The Celtic Britons under Rome". In Green, Miranda (ed.). The Celtic World. Routledge. p. 623.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Koch, John (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 291–292.

- ISBN 0415178940.

- ^ Forsyth, p. 9.

- ^ "The Germanic invasions of Britain". www.uni-due.de.

- ^ Scottish Archaeological Research Framework (ScARF), Highland Framework, Early Medieval (accessed May 2022).

- ISBN 0-631-22260-X.

- ^ ISBN 0-19-280202-X.

- OED s.v. "Briton." See also Online Etymology Dictionary: Briton

- )

- ^ McCone, Kim (2013). "The Celts: questions of nomenclature and identity", in Ireland and its Contacts. University of Lausanne. p.25

- ^ "brythonic | Origin and meaning of Brythonic by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ "Briton". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ While there have been attempts in the past to align the Pictish language with non-Celtic language, the current academic view is that it was Brittonic. See: Forsyth (1997) p. 37: "[T]he only acceptable conclusion is that, from the time of our earliest historical sources, there was only one language spoken in Pictland, the most northerly reflex of Brittonic."

- ^ Forsyth 2006, p. 1447; Forsyth 1997; Fraser 2009, pp. 52–53; Woolf 2007, pp. 322–340

- ISBN 019-910035-7.

- ^ Hunter, Fraser (of Museum of Scotland), Carnyx and Co- piece by Hunter on the carnyx

- OCLC 24541026.

- ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- )

- S2CID 216484936.

- ^ PMID 34937049.

- ^ a b "Ancient DNA study reveals large scale migrations into Bronze Age Britain". University of York. 22 December 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ "Ancient mass migration transformed Britons' DNA". BBC News. 22 December 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ "The Avalon Project". Yale Law School. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ a b Sullivan, Rory (10 April 2020). "Ancient Britons didn't eat hares or chickens -- they venerated them". CNN. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ a b Magazine, Smithsonian; Fox, Alex. "Hares and Chickens Were Revered as Gods—Not Food—in Ancient Britain". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico 2.4, 5.2

- ^ Pattison, John E. (2011) "Integration versus Apartheid in post-Roman Britain: a Response to Thomas et al. (2008)", Human Biology, Vol. 83: Iss. 6, Article 9. pp. 715–733.

- ^ "Kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons - Deira". www.historyfiles.co.uk.

- ^ Nennius (c. 828). History of the Britons. Chapter 6: "Cities of Britain".

- ^ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 515–516.

- ^ Bromwich, p. 157.

- ^ Chadwick, H. M.; Chadwick, N. K. (1940). The Growth of Literature. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ ISBN 0-7099-0040-6.

- ^ Broun, "Dunkeld", Broun, "National Identity", Forsyth, "Scotland to 1100", pp. 28–32, Woolf, "Constantine II"; cf. Bannerman, "Scottish Takeover", passim, representing the "traditional" view.

- ^ Charles-Edards, pp. 12, 575; Clarkson, pp. 12, 63–66, 154–158

- ^ "Germanic invaders may not have ruled by apartheid". New Scientist, 23 April 2008.

- ^ Williams, Ann and Martin, G. H. (tr.) (2002). Domesday Book: a complete translation. London: Penguin, pp. 341–357.

- ISBN 978-84-95622-58-7.

- ^ a b Schiffels et al. 2016, p. 1.

- ^ Schiffels et al. 2016, p. 3, Table 1.

- ^ Schiffels et al. 2016, p. 5.

- ^ a b Martiniano et al. 2018, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b Martiniano et al. 2018, p. 3, Table 1.

- ^ a b Martiniano et al. 2018, p. 6. "Six of the seven individuals sampled here are clearly indigenous Britons in their genomic signal. When considered together, they are similar to the earlier Iron-Age sample, whilst the modern group with which they show closest affinity are Welsh. These six are also fixed for the Y-chromosome haplotype R1b-L51, which shows a cline in modern Britain, again with maximal frequencies among western populations. Interestingly, these people do not differ significantly from modern inhabitants of the same region (Yorkshire and Humberside) suggesting major genetic change in Eastern Britain within the last millennium and a half. That this could have been, in part, due to population influx associated with the Anglo-Saxon migrations is suggested by the different genetic signal of the later Anglo-Saxon genome."

- ^ Martiniano et al. 2018, pp. 1.

- ^ Martiniano et al. 2018, pp. 1, 6.

Bibliography

- Martiniano, Rui; et al. (19 January 2016). "Genomic signals of migration and continuity in Britain before the Anglo-Saxons". PMID 26783717.

- ISBN 90-802785-5-6.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- Schiffels, Stephan; et al. (19 January 2016). "Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon genomes from East England reveal British migration history". PMID 26783965.

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2011.