Brown thrasher

| Brown thrasher | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult in New York, U.S. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Mimidae |

| Genus: | Toxostoma |

| Species: | T. rufum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Toxostoma rufum | |

| |

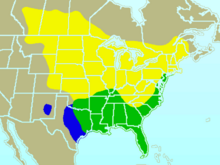

| Range of T. rufum Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range

| |

| Synonyms | |

The brown thrasher (Toxostoma rufum), sometimes erroneously called the brown thrush or fox-coloured thrush, is a

As a member of the genus Toxostoma, the bird is relatively large-sized among the other thrashers. It has brown upper parts with a white under part with dark streaks. Because of this, it is often confused with the smaller wood thrush (Hylocichla mustelina), among other species. The brown thrasher is noted for having over 1000 song types, and the largest song repertoire of birds.[3] However, each note is usually repeated in two or three phrases.

The brown thrasher is an omnivore, with its diet ranging from insects to fruits and nuts. The usual nesting areas are shrubs, small trees, or at times on ground level. Brown thrashers are generally inconspicuous but territorial birds, especially when defending their nests, and will attack species as large as humans.[4]

Taxonomy and naming

The brown thrasher was originally described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae as Turdus rufus.[5] The genus name Toxostoma comes from the Ancient Greek toxon, "bow" or "arch" and stoma, "mouth". The specific rufum is Latin for "red", but covers a wider range of hues than the English term.[6]

Although not in the thrush family, this bird is sometimes erroneously called the brown thrush.[7] The name misconception could be because the word thrasher is believed to derive from the word thrush.[8][9] The naturalist Mark Catesby called it the fox-coloured thrush.[10]

Genetic studies have found that the brown thrasher is most closely related to the long-billed and Cozumel thrashers (T. longirostre & guttatum), within the genus Toxostoma.[11][12]

Description

The brown thrasher is bright reddish-brown above with thin, dark streaks on its buffy underparts.[13] It has a whitish-colored chest with distinguished teardrop-shaped markings on its chest. Its long, rufous tail is rounded with paler corners, and eyes are a brilliant yellow. Its bill is brownish, long, and curves downward. Both male and females are similar in appearance.[14] The juvenile appearance of the brown thrasher from the adult is not remarkably different, except for plumage texture, indiscreet upper part markings, and the irises having an olive color.[10]

The brown thrasher is a fairly large passerine, although it is generally moderate in size for a thrasher, being distinctly larger than the

The lifespan of the brown thrasher varies on a year-to-year basis, as the rate of survival the first year is 35%, 50% in between the second and third year, and 75% between the third and fourth year.[14] Disease and exposure to cold weather are among contributing factors for the limits of the lifespan. However, the longest lived thrasher in the wild is 12 years, and relatively the same for ones in captivity.[14]

Similar species

The similar-looking long-billed thrasher has a significantly smaller range.[18] It has a gray head and neck, and has a longer bill than the brown thrasher.[10] The brown thrasher's appearance is also strikingly similar to the wood thrush, the bird that it is usually mistaken for.[10] However, the wood thrush has dark spots on its under parts rather than the brown thrashers' streaks, has dark eyes, shorter tail, a shorter, straighter bill (with the head generally more typical of a thrush) and is a smaller bird.[10][19]

Distribution and habitat

The brown thrasher resides in various habitats. It prefers to live in woodland edges, thickets and dense brush,[20] often searching for food in dry leaves on the ground.[21] It can also inhabit areas that are agricultural and near suburban areas, but is less likely to live near housing than other bird species.[10][14] The brown thrasher often vies for habitat and potential nesting grounds with other birds, which is usually initiated by the males.[14]

The brown thrasher is a strong, but partial migrant, as the bird is a year-round resident in the

Behavior

The brown thrasher has been observed either solo or in pairs. The brown thrasher is usually an elusive bird, and maintains its evasiveness with low-level flying.[30][31] When it feels bothered, it usually hides into thickets and gives cackling calls.[31] Thrashers spend most of their time on ground level or near it. When seen, it is commonly the males that are singing from unadorned branches.[32] The brown thrasher has been noted for having an aggressive behavior,[33] and is a staunch defender of its nest.[14] However, the name does not come from attacking perceived threats, but is believed to have come from the thrashing sound the bird makes when digging through ground debris.[14][34] It is also thought that the name comes from the thrashing sound that is made while it is smashing large insects to kill and eventually eat.[35]

Feeding

This bird is

The brown thrasher utilizes its vision while scouring for food. It usually forages for food under leaves, brushes, and soil debris on the ground using its bill.

Breeding

Brown thrashers are typically monogamous birds, but mate-switching does occur, at times during the same season.[36][50] Their breeding season varies by region. In the southeastern United States, the breeding months begin in February and March, while May and June see the commencement of breeding in the northern portion of their breeding range. When males enter the breeding grounds, their territory can range from 2 to 10 acres (0.81 to 4.05 ha).[50][51] Around this time of the year the males are usually at their most active, singing loudly to attract potential mates, and are found on top of perches.[36][52] The courting ritual involves the exchanging of probable nesting material. Males will sing gentler as they sight a female, and this enacts the female to grab a twig or leaf and present it to the male, with flapping wings and chirping sounds. The males might also present a gift in response and approach the female.[53][54] Both sexes will take part in nest building once mates find each other, and will mate after the nest is completed.[14]

The female lays 3 to 5

Vocal development

The male brown thrasher may have the largest song repertoire of any North American bird, which has been documented as at least over 1,100 songs.

In the birds' youth, alarm noises are the sounds made.

Predation and threats

Although this bird is widespread and still common, it has declined in numbers in some areas due to loss of suitable

The brown thrasher methods of defending itself include using its bill, which can inflict significant damage to species smaller than it, along with wing-flapping and vocal expressions.[75]

State bird

The brown thrasher is the

References

- . Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ Barrows, W.B. (1912). "Brown Thrasher" in Michigan bird life. Michigan Agricultural College. Lansing, Michigan, p. 661.

- ISBN 978-0-521-41799-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-873403-95-2.

- ^ Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Tomus I. Editio Decima, Reformata (in Latin). Vol. 1. Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 169.

- ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ "Mimic Thrush". Columbia Encyclopedia (sixth edition). 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7614-7775-4.

- ^ Schaars, H. W. "The Origin of the Common Names of Wisconsin Birds" (PDF). The Passenger Pigeon. 13 (1): 15–18. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-873403-95-2.

- JSTOR 4089682.

- PMID 21867766.

- ISBN 978-0-7566-5868-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Gray, Philip (2007). "Toxostoma rufum". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-679-45122-8.

- ^ "Taxostoma rufum". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ a b Bent, Arthur Cleveland (1948). Life histories of North American nuthatches, wrens, thrashers and their allies (PDF). Smithsonian Institution United States National Museum Bulletin. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. pp. 374–375.

- ^ "Brown Thrasher". The University of Georgia: Museum of Natural History. Georgia Museum of Natural History. 2008. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ISBN 978-1582380919.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-9696134-0-4.

- ^ "Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission: A collaborative study of Florida's birdlife" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-520-23593-9.

- ^ "Passeriformes: Incertae Sedis – Mimidae. Schiffornis turdinus (Wied). Thrush-like Schiffornis" (PDF). AOU Checklist of North American Birds. American Ornithologists' Union. 1998. p. 416. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-18. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- ^ doi:10.2173/bna.557

- S2CID 86276981.

- S2CID 84426970.

- S2CID 85425945.

- ISBN 978-0-395-79514-9.

- ^ "Brown Thrasher in Dorset: a species new to Britain and Ireland" (PDF). britishbirds.co.uk. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-873403-95-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-1426207204.

- ISBN 978-1-873403-95-2.

- ^ Partin H. (1977). Breeding Biology and Behavior of the Brown Thrasher, (Toxostoma rufum) (PDF). Ph.D. Thesis, The Ohio State University, United States (Thesis). Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-89577-351-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7614-7285-8.

- ^ a b c "Gray Catbird, Northern Mockingbird and Brown Thrasher" (PDF). Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ^ a b Beal, F. E. L.; W. L. McAtee; E. R. Kalmbach (1916). Common birds of southeastern United States in relation to agriculture. U.S. Dep. Agric. Farmer's Bull. 755. USDA. p. 11.

- ^ a b Graber R. R.; Graber J. W.; Kirk E. L. (1970). "Illinois birds: Mimidae". Ill. Nat. Hist. Surv. Biol. Notes. 68: 3–38.

- JSTOR 4154409.

- ISBN 978-1-56037-241-7.

- ^ a b Cornell Lab of Ornithology. "The Project FeederWatch Top 20 feeder birds in the Southeast" (PDF). Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- JSTOR 1367503.

- ^ Bent, A. C. (1948). "Life histories of North American nuthatches, wrens, thrashers, and their allies". U.S. Natl. Mus. Bull. p. 195.

- ISBN 978-0-7614-7775-4.

- ^ Engels, W. (1940). "Structural adaptations in thrashers (Mimidae: genus Toxostoma) with comments on interspecific relations". Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. 42: 341–400.

- S2CID 85187112.

- ISBN 978-0486234977.

- ^ Hilton, B. Jr. (1992). "Tool-making and tool-using by a Brown Thrasher (Toxostoma rufum)". Chat. 56: 4–5.

- ^ Howard, R. R.; Brodie, E. D. Jr. (1970). "A mimetic relationship in salamanders: Notophthalmus viridescens and Pseudotriton ruber". Am. Zool. 10: 475.

- ^ ISBN 978-0811728218.

- ISBN 978-0-8117-2680-1.

- JSTOR 4085282.

- ISBN 978-0-292-77119-2.

- ISBN 978-0-87745-561-5.

- ISBN 978-1-58465-749-1.

- ISBN 978-1-58465-749-1.

- ^ "Species: Brown Thrasher Toxostoma rufum". Vancouver Avian Research Centre. Vancouver Avian Research Centre. 2012. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-618-40568-8.

- ISBN 978-0-19-530901-0.

- ^ "All About Birds". Cornell University. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "Thrasher". TropicalBirds.com. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "Brown Thrasher". Outdoor Alabama. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-19-530901-0.

- JSTOR 4081470.

- ISBN 978-0811729635.

- ISBN 978-0-618-23648-0.

- ^ "Brown Thrasher (Toxostoma rufum) – Michigan Bird Atlas" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "New Jersey Endangered and Threatened Species Field Guide". Archived from the original on 2014-05-08. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ "BROWN THRASHER (Toxostoma rufum): Guidance for Conservation" (PDF). audubon.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ BirdLife International (2012). "LC: Brown Thrasher Toxostoma rufum". IUCN Red List for birds. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ S2CID 84032938.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8117-2680-1.

- ISBN 978-1-81174-522-9.

- ISBN 978-1-81174-522-9.

- ^ a b "Facts about Brown Thrasher: Encyclopedia of Life". Archived from the original on 2011-10-16. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ^ Cavitt, J. F. (1998). The role of food supply and nest predation in limiting reproductive success of Brown Thrashers (Toxostoma rufum): effects of predator removal, food supplements and predation risk. Phd Thesis. Kansas State Univ. Manhattan.

- ^ Toland, B. (1985). "Food habits and hunting success of Cooper's Hawks in Missouri". Journal of Field Ornithology. 56 (4 (Autumn)): 419–422.

- ^ Curnutt, J. (2007). Conservation Assessment for Northern Goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) Linnaeus in the Western Great Lakes. USDA Forest Service. 105 pp.

- ^ Burns, F. L. (1911). "A monograph of the Broad-winged Hawk (Buteo platypterus)". The Wilson Bulletin. 23 (3–4): 143–320.

- JSTOR 4088628.

- ^ Ward, F. P., & Laybourne, R. C. (1985). A difference in prey selection by adult and immature peregrine falcons during autumn migration. Conservation studies on raptors. Page Brothers, Norwich, England, pp. 303–309.

- from the original on September 24, 2017.

- ^ Murphy, R. K. (1997). Importance of prairie wetlands and avian prey to breeding Great Horned Owls (Bubo virginianus) in northwestern North Dakota. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station, pp. 286–298.

- ^ JSTOR 1363563.

- ISBN 978-0-7614-1862-7.

External links

- Brown Thrasher (BirdHouses101.com)

- Photo and links to additional pages at GeorgiaInfo

- Reproduction of Audubon's description

- "Brown Thrasher media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Stamps[usurped] at bird-stamps.org

- Brown Thrasher Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Brown Thrasher Bird Sound at Florida Museum of Natural History

- Brown Thrasher photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)