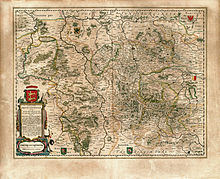

Principality of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

Principality of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel Fürstentum Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (German) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1269–1815 | |||||||||||

Saxon Circle (Lower Saxon Circle from 1512) | 1500 | ||||||||||

• Regained Calenberg and Göttingen | 1584 | ||||||||||

• Occupied Grubenhagen | 1596–1617 | ||||||||||

• Wolfenbüttel line extinct; Calenberg and Göttingen to House of Hanover | 1635 | ||||||||||

• Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern split off | 1667–1735 | ||||||||||

• Annexed to the Kingdom of Westphalia (Napoleonic Wars) | 1807–1813 | ||||||||||

• Formally re-established as the Duchy of Brunswick | 1815 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Principality of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (German: Fürstentum Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel) was a subdivision of the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg, whose history was characterised by numerous divisions and reunifications.[citation needed] It had an area of 3,828 square kilometres in the mid 17th century.[1] Various dynastic lines of the House of Welf ruled Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel until the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. As a result of the Congress of Vienna, its successor state, the Duchy of Brunswick, was created in 1815.

History

Middle Ages

After

The area of Brunswick(-Wolfenbüttel) was further subdivided in the succeeding decades. For example, the lines of Grubenhagen and Göttingen were split for a while. In a similar way, in 1432 the estates between the Deister hills and the Leine river, that had been gained in the meantime from the Middle House of Brunswick, split away to form the Principality of Calenberg. There were further reunifications and divisions.

In the meanwhile the dukes became weary of the constant disputes with the citizens of the town of Brunswick and, in 1432, moved their

Following the twelfth division of the duchy in 1495, whereby the Principality of Brunswick-Calenberg-Göttingen was re-divided into its component territories, Duke

Early modern times

The reigns of dukes

In 1500 Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel became part of the Lower Saxon Circle within the Holy Roman Empire.

From 1519 to 1523 the principality went to war with the

In the

In 1571 the castle and village of

In 1635 Duke

In 1735 when the dynastic line died out another collateral line emerged: the Brunswick-Bevern line founded in 1666.

In 1753–1754 the residence of the dukes of Wolfenbüttel returned to Brunswick, to the newly built Brunswick Palace.

The town thus lost the independence it had enjoyed since the 15th century. In the process, the duke followed the trend and did not interfere with anything, including work on the new castle, begun in 1718 by Hermann Korb on the Grauer Hof which was still not finished. The effect on Wolfenbüttel was catastrophic, as can be seen from the timber-framed houses built later on. 4,000 townsfolk followed the ducal family and Wolfenbüttel's population sank from 12,000 to 7,000. Only the archives, the ecclesiastical office and the library remained as a link to earlier times. From Brunswick there were jibes that Wolfenbüttel had deteriorated into a "widows' residence" (Witwensitz).

The extensive gardens in front of the three town gates (the Herzogtor, Harztor and Augusttor) were leased to the former gardeners as an emphyteusis. As a consequence jam factories were established which were characteristic of Wolfenbüttel until the 20th century. In front of the Herzogtor, the number of gardens grew, until they eventually reached the Lechlum Wood (Lechlumer Holz). Its southern edge was graced by the little Lustschloss of Antoinettenruh, built in 1733 instead of a garden house, a work by the master builder, Hermann Korb, who was so important to Wolfenbüttel. Wolfenbüttel became a town of schools. In 1753 the teachers' training college was founded, which began in the orphanage and later moved to the building of the present-day Harztorwall School.

Politically Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel was one of

During Charles I's era, there were great achievements in the cultural and scientific fields: the theatre was promoted and education encouraged. In 1753 the ducal art and natural history collection—forerunner of the Natural History Museum—was founded. These substantial collections had been amassed by the Brunswick dukes. This enterprise was supported by

In August 1784

The secret mission was disguised as a family visit at the time of the Autumn Fair. court life determined the timing of the stay in the Residenz castle on Bohlweg.

Napoleonic era and transfer to the Duchy of Brunswick

As a result of the

After the end of Napoleonic rule the state was re-established under the name of the Duchy of Brunswick.

Collateral line in Bevern

The Principality of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel-Bevern emerged from an inheritance dispute between

Economic and social history

The role of farmers

According to Bornstedt

With the Brunswick redemption law (Ablösungsordnung) of 20 December 1834 by the state's legal successor, the Duchy of Brunswick, the dependence of the farmers was abolished. Farmers could now purchase the land freehold and the money required could be loaned from the ducal lending office. At the end of the 19th century Flurbereinigung or land consolidation took place.

See also

- List of the rulers of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

- List of rulers of the House of Welf

References

- ISBN 1135370532.

- OCLC 180492556

- ^ Bornstedt, Wilhelm (ed), Aus der Geschichte von Rautheim an der Wabe, pp. 28 ff.

Sources

- Wilhelm Havemann: Geschichte der Lande Braunschweig und Lüneburg. 3 vols. Repr. Hirschheydt, Hannover 1974–75, ISBN 3-7777-0843-7 (Original ed: Verlag der Dietrich'schen Buchhandlung, Göttingen 1853–1857, online at Google Books) (in German)

- Hans Patze (et al.): Geschichte Niedersachsens. 7 vols. Hahnsche Buchhandlung, Hannover 1977- (Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Niedersachsen und Bremen, 36) (in German) (Publisher's summary)

- Gudrun Pischke: Die Landesteilungen der Welfen im Mittelalter. Lax, Hildesheim 1987, ISBN 3-7848-3654-2(in German)

External links

- The House of Welf

- Karte von Niedersachsen am Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts

- Zur Rolle der Bauern im Duchy of BS-WF auf der Cremlingen.de

- Castle of the House of Welf at Wolfenbüttel