Buddhism and Jainism

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

Buddhism and Jainism are two

History

Jainism is an ancient religion whose own historiography centres on its 24 guides or

Buddhist scriptures record that during Prince Siddhartha's ascetic life (before attaining enlightenment) he undertook many fasts, penances and austerities, the descriptions of which are elsewhere found only in the Jain tradition[

Thus far, Sāriputta, did I go in my penance? I went without clothes. I licked the food from my hands. I took no food that was brought or meant especially for me. I accepted no invitation to a meal.

The Jain text of

-

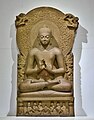

JainKushana, Mathura

-

Buddha,Kushana, Mathura

-

Sahastrakoot (1008) Jinalaya, Bhadrakali in Itury

-

Multiple depictions of Buddha on a wall at Ajanta Caves

Jainism in Buddhist Texts

Pāli Canon

The

The five vows (non-violence,

Buddhist writings reflect that Jains had followers by the time the Buddha lived. Suggesting close correlations between the teachings of the Jains and the Buddha, the Majjhima Nikaya relates dialogues between the Buddha and several members of the "Nirgrantha community".[citation needed]

Indian Buddhist tradition categorized all non-Buddhist schools of thought as pāsaṇḍa "heresy" (pasanda means to throw a noose or pasha—stemming from the doctrine that schools labelled as Pasanda foster views perceived as wrong because they are seen as having a tendency towards binding and ensnaring rather than freeing the mind). The difference between the schools of thought are outlined.

Divyavadana

The ancient text Divyavadana (Ashokavadana is one of its sections) mention that in one instance, a non-Buddhist in Pundravardhana drew a picture showing the Buddha bowing at the feet of Mahavira. On complaint from a Buddhist devotee, Ashoka, the Maurya Emperor, issued an order to arrest him, and subsequently, another order to kill all the Ājīvikas in Pundravardhana. Around 18,000 Ājīvikas were executed as a result of this order.[18] Sometime later, another ascetic in Pataliputra drew a similar picture. Ashoka burnt him and his entire family alive in their house.[19] He also announced an award of one dinara (silver coin) to anyone who brought him the head of a Jain. According to Ashokavadana, as a result of this order, his own brother, Vitashoka, was mistaken for a heretic and killed by a cowherd. Their ministers advised that "this is an example of the suffering that is being inflicted even on those who are free from desire" and that he "should guarantee the security of all beings". After this, Ashoka stopped giving orders for executions.[18]

According to K. T. S. Sarao and Benimadhab Barua, stories of persecutions of rival sects by Ashoka appear to be a clear fabrication arising out of sectarian propaganda.[19][20][21]

Buddhist Texts in Jain Libraries

According to Padmanabh Jaini, Vasudhara Dharani, a Buddhist work was among the Jainas of Gujarat in 1960s, and a manuscript was copied in 1638 CE.[22] The Dharani was recited by non-Jain Brahmin priests in private Jain homes.

-

Buddha with Mucalinda Naga, Sri Lanka

-

Parshvanatha with Dharanendra

The shared terms include

Similarities

-

Jain Stupa, Kankali Tila

-

Buddhist stupa worship, Sanchi

-

Mahaveer - Nagamalai Puthukottai, Tamil Nadu, ardha-padmasana

-

Tirthankara Sravanabelgola, Kayotsarga sana

-

Buddha - Kushan Period, standing

In

Karakandu, a

The

Jain and Buddhist iconography can be similar. In north India, the sitting Jain and Buddhist images are in padmasana, whereas in South India both Jain and Buddhist images are in ardha-padmasana (also termed virasana in Sri Lanka). However the Jain images are always samadhi mudra, whereas the Buddha images can also be in bhumi-sparsha, dharam-chakra-pravartana and other mudras. The standing Jain images are always in khadgasana or kayotsarga asana.

Differences

-

TheravadaBuddhist monk, Thailand

-

Digambara Jain monk, India

Jainism has refined the non-violence (Ahimsa) doctrine to an extraordinary degree where it is an integral part of the Jain culture.

Although both Buddhists and Jain had orders of nuns, Buddhist Pali texts record the Buddha saying that a woman has the ability to obtain

Jains believe in the existence of an eternal

The Anekantavada doctrine is another key difference between Jainism and Buddhism. The Buddha taught the Middle Way, rejecting extremes of the answer "it is" or "it is not" to metaphysical questions. The Mahavira, in contrast, accepted both "it is" and "it is not", with "perhaps" qualification and with reconciliation.[36]

Jainism discourages monks and nuns from staying in one place for long, except for 4 months in the rainy season (

See also

References

Citations

- ISBN 0028657187; p. 383

- ^ ISBN 978-1-136-98588-1.

- ^ Zimmer 1953, p. 266.

- ISBN 978-1-134-90352-8. Archivedfrom the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2017., Quote: "...Buddha's teaching that beings have no soul, no abiding essence. This 'no-soul doctrine' (anatta-vada) he expounded in his second sermon."

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 30–33.

- ^

ISBN 0-86013-072-X.

- ^ Vicittasarabivamsa, U (1992). "Chapter IX: The chronicle of twenty-four Buddhas". In Ko Lay, U; Tin Lwin, U (eds.). The great chronicle of Buddhas, Volume One, Part Two (PDF) (1st ed.). Yangon, Myanmar: Ti=Ni Publishing Center. pp. 130–321. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ Law, Bimala Churn, ed. (1938). "The lineage of the Buddhas". The Minor Anthologies of the Pali Canon: Buddhavaṃsa, the lineage of the Buddhas, and Cariyā-Piṭaka or the collection of ways of conduct (1st ed.). London: Milford.

- ^ Takin, MV, ed. (1969). "The lineage of the Buddhas". The Genealogy of the Buddhas (1st ed.). Bombay: Bombay University Publications.

- ^ Jataka Archived 8 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopœdia Britannica.

- ISBN 978-81-71418664. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ISBN 0-7007-1538-X. Note: ISBN refers to the UK:Routledge (2001) reprint of original text published in 1884

- ^ Jain & Upadhye 2000, p. 58.

- ^ Collins 2000, p. 204.

- ^ ""Majjhimanikāya – Upāli Sutta" (MN 56)". Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ a b Sangave 2001, p. 21.

- ^ Zimmer 1953, p. 223.

- ^ ISBN 978-81-208-0616-0. Archivedfrom the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-152-74433-2. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-59884-078-0. Archivedfrom the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-9844043-0-8. Archivedfrom the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ Vasudhara dharani A Buddhist work in use among the Jainas of Gujarat, Padmanabh S Jaini, Mahavir Jain_Vidyalay Suvarna_Mahotsav Granth Part 1, 2002, p. 30-45.

- ^ Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism, Johannes Bronkhorst, Brill, 2011, p. 132

- ^ Zimmer 1953, p. 474.

- ^ Sangave 2001, p. 139.

- ^ Patrick Olivelle 2006, p. 396.

- ^ [Ascetic Figures Before and in Early Buddhism: The Emergence of Gautama as the Buddha, Issue 30 of Religion and reason, ISSN 0080-0848, Martin G. Wiltshire, Walter de Gruyter, 1990p. 112]

- ^ "RISHI BHASHIT AND PRINCIPLES OF JAINISM By Dr. Sagar Mal Jain". Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Winternitz 1993, pp. 408–409.

- ^ Sangave 1980, p. 260.

- ISBN 9780520068209. Archivedfrom the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- ^ Sangave 2001, p. 140.

- ISBN 978-8120801585, page 63, Quote: "The Buddhist schools reject any Ātman concept. As we have already observed, this is the basic and ineradicable distinction between Hinduism and Buddhism".

- ISBN 978-0815336112, page 33

- ^ Matilal 1998, pp. 128–135.

Sources

- Collins, Randall (2000), The sociology of philosophies: a global theory of intellectual change, ISBN 978-0674001879

- ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Matilal, Bimal Krishna (1990), Logic, Language and Reality: Indian Philosophy and Contemporary Issues, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0717-4

- Matilal, Bimal Krishna (1998), Ganeri, Jonardon; Tiwari, Heeraman (eds.), The Character of Logic in India, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-3739-1

- ISBN 978-0-19-530532-6

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001a), Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture, Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-839-2

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001), Aspects of Jaina Religion, ISBN 978-81-263-0720-3

- ISBN 978-0-317-12346-3

- Jain, Hiralal; Upadhye, Dr. Adinath Neminath (2000), Mahavira his Times and his Philosophy of Life, Bharatiya Jnanpith

- ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6.

- ISBN 978-81-208-0265-0