Bufotenin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | N,N-Dimethyl-5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-Hydroxy-dimethyltryptamine; Bufotenine; Cebilcin |

| Routes of administration | Oral, intravenous |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 146 to 147 °C (295 to 297 °F) |

| Boiling point | 320 °C (608 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

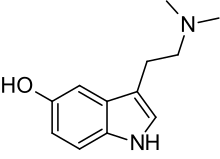

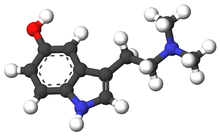

Bufotenin (5-HO-DMT, bufotenine) is a

The name bufotenin originates from the toad genus

Nomenclature

Bufotenin (bufotenine) is also known by the chemical names 5-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (5-HO-DMT), N,N-dimethyl-5-hydroxytryptamine, dimethyl serotonin, and mappine.[2]

History

Bufotenin was isolated from toad skin, and named by the Austrian chemist Handovsky at the

Sources

Toads

Bufotenin is found in the skin and eggs of several species of toads belonging to the genus

The toad was "recurrently depicted in

In addition to bufotenin, Bufo secretions also contain digoxin-like cardiac glycosides, and ingestion of these toxins can be fatal. Ingestion of Bufo toad poison and eggs by humans has resulted in several reported cases of poisoning,[7][8][9] some of which resulted in death. A court case in Spain, involving a physician who dosed people with smoked Mexican Toad poison, one of his customers died after inhaling three doses, instead of the usual of only one, had images of intoxicated with this smoke suffering obvious hypocalcemic hand muscular spasms.[9][10][11]

Reports in the mid-1990s indicated that bufotenin-containing toad secretions had appeared as a

Bufotenin is also present in the skin secretion of three arboreal hylid frogs of the genus

Anadenanthera seeds

Bufotenin is a constituent of the

Other sources

Bufotenin has been identified as a component in the latex of the takini (Brosimum acutifolium) tree, which is used as a psychedelic by South American shamans,[22] and in the seeds of Mucuna pruriens. [23] Bufotenin has also been identified in Amanita citrina, A. porphyria, and A. tomentella. [24] [25]

Pharmacology

Uptake and elimination

In rats,

Lethal dose

The acute toxicity (LD50) of bufotenin in rodents has been estimated at 200 to 300 mg/kg. Death occurs by respiratory arrest.[19] In April 2017, a South Korean man died of bufotenin poisoning after consuming toads that had been mistaken for edible Asian bullfrogs,[27] while in Dec. 2019, five Taiwanese men became ill and one man died after eating Central Formosa toads that they mistook for frogs.[28]

Effects in humans

Fabing & Hawkins (1955)

In 1955, Fabing and Hawkins administered bufotenin intravenously at doses of up to 16 mg to prison inmates at Ohio State Penitentiary.[29] A toxic effect causing purpling of the face was seen in these tests.

A subject given 1 mg reported "a tight feeling in the chest" and prickling "as if he had been jabbed by needles." This was accompanied by a "fleeting sensation of pain in both thighs and a mild nausea."[29]

Another subject given 2 mg reported "tightness in his throat." He had tightness in the stomach, tingling in pretibial areas, and developed a purplish hue in the face indicating blood circulation problems. He vomited after 3 minutes.[29]

Another subject given 4 mg complained of "chest oppression" and that "a load is pressing down from above and my body feels heavy." The subject also reported "numbness of the entire body" and "a pleasant Martini feeling-my body is taking charge of my mind." The subject reported he saw red spots passing before his eyes and red-purple spots on the floor, and the floor seemed very close to his face. Within 2 minutes these visual effects were gone, and replaced by a yellow haze, as if he were looking through a lens filter.[29]

Fabing and Hawkins commented that bufotenin's psychedelic effects were "reminiscent of LSD and mescaline but develop and disappear more quickly, indicating rapid central action and rapid degradation of the drug".[citation needed]

Isbell (1956)

In 1956,

Turner & Merlis (1959)

Turner and Merlis (1959)[30] experimented with intravenous administration of bufotenin (as the water-soluble creatinine sulfate salt) to schizophrenics at a New York state hospital. They reported that when one subject received 10 mg during a 50-second interval, "the peripheral nervous system effects were extreme: at 17 seconds, flushing of the face, at 22 seconds, maximal inhalation, followed by maximal hyperventilation for about 2 minutes, during which the patient was unresponsive to stimuli; her face was plum-colored." Finally, Turner and Merlis reported:

on one occasion, which essentially terminated our study, a patient who received 40 mg intramuscularly, suddenly developed an extremely

auricular fibrillation . . . extreme cyanosisdeveloped. Massage over the heart was vigorously executed and the pulse returned to normal . . . shortly thereafter the patient, still cyanotic, sat up saying: "Take that away. I don't like them."

After pushing doses to the morally admissible limit without producing visuals, Turner and Merlis conservatively concluded: "We must reject bufotenine . . . as capable of producing the acute phase of Cohoba intoxication."[3]

McLeod and Sitaram (1985)

A 1985 study by McLeod and Sitaram in humans reported that bufotenin administered intranasally at a dose of 1–16 mg had no effect, other than intense local irritation. When given intravenously at low doses (2–4 mg), bufotenin oxalate caused anxiety but no other effects; however, a dose of 8 mg resulted in profound emotional and perceptual changes, involving extreme anxiety, a sense of imminent death, and visual disturbance associated with color reversal and distortion, and intense flushing of the cheeks and forehead.[31]

Ott (2001)

In 2001, ethnobotanist

Ott reported "visionary effects" of intranasal bufotenin and that the "visionary threshold dose" by this route was 40 mg, with smaller doses eliciting perceptibly psychoactive effects. He reported that "intranasal bufotenine is throughout quite physically relaxing; in no case was there facial rubescence, nor any discomfort nor disesteeming side effects".At 100 mg, effects began within 5 minutes, peaked at 35–40 minutes, and lasted up to 90 minutes. Higher doses produced effects that were described as psychedelic, such as "swirling, colored patterns typical of tryptamines, tending toward the arabesque". Free base bufotenin taken sublingually was found to be identical to intranasal use. The potency, duration, and psychedelic action was the same. Ott found vaporized free base bufotenin active from 2–8 mg with 8 mg producing "ring-like, swirling, colored patterns with eyes closed". He noted that the visual effects of insufflated bufotenin were verified by one colleague, and those of vaporized bufotenin by several volunteers.

Ott concluded that free base bufotenin taken intranasally and sublingually produced effects similar to those of

Association with schizophrenia and other mental disorders

A study conducted in the late 1960s reported the detection of bufotenin in the urine of schizophrenic subjects;[33] however, subsequent research failed to confirm these findings until 2010.[34][35][36][37][38]

Studies have detected endogenous bufotenin in urine specimens from individuals with other psychiatric disorders,[39] such as infant autistic patients.[40] Another study indicated that paranoid violent offenders or those who committed violent behaviour towards family members have higher bufotenin levels in their urine than other violent offenders.[41]

A 2010 study utilized a mass spectrometry approach to detect levels of bufotenin in the urine of individuals with severe autism spectrum disorder (ASD), schizophrenia, and asymptomatic subjects. Their results indicate significantly higher levels of bufotenin in the urine of the ASD and schizophrenic groups when compared to asymptomatic individuals.[38]

Legal status

Australia

Bufotenin is classified as a Schedule I controlled substance according to the Criminal Code Regulations of the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia.[42] It is also listed as a Schedule 9 substance under the Poisons Standard (October 2015).[43] A schedule 9 drug is outlined in the Poisons Act 1964 as "Substances which may be abused or misused, the manufacture, possession, sale or use of which should be prohibited by law except when required for medical or scientific research, or for analytical, teaching or training purposes with approval of the CEO."[44]

Under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1981 6.0 grams (0.21 oz) is determined to be enough for court of trial and 2.0 grams (0.071 oz) is considered intent to sell and supply.[45]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, bufotenin is a Class A drug under the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act.

United States

Bufotenin (DEA Drug Code 7403) is regulated as a Schedule I drug by the Drug Enforcement Administration at the federal level in the United States and is therefore illegal to buy, possess, and sell.[46]

Sweden

Sweden's public health agency suggested classifying Bufotenin as a hazardous substance, on May 15, 2019.[47]

See also

- 5-HO-DiPT

- Hamilton's Pharmacopeia

- List of entheogens

- O-Acetylbufotenine

- Tryptamines

- Cane toad

- Colorado River toad

- Anadenanthera colubrina

- Anadenanthera peregrina

References

- ^ Bufo Alvarius. AmphibiaWeb. Accessed on May 6, 2007.

- ^ "DEA Drug Scheduling". U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Archived from the original on 2008-10-20. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ PMID 392119.

- .

- ^ S2CID 162875250.

- S2CID 143698915.

- PMID 3702971.

- ^ Ragonesi DL (1990). "The boy who was all hopped up". Contemporary Pediatrics. 7: 91–4.

- ^ PMID 8915235.

- PMID 12639891.

- ISBN 978-1-84103-006-7.

- ^ Rodrigues, R.J. Aphrodisiacs through the Ages: The Discrepancy Between Lovers' Aspirations and Their Desires. ehealthstrategies.com

- PMID 7476839.

- ^ The Dog Who Loved to Suck on Toads. NPR. Accessed on May 6, 2007.

- Psychoactive toad: Cultural references

- ^ Most, A. "Bufo avlarius: The Psychedelic Toad of the Sonoran Desert". erowid.org. Retrieved 2007-08-12.

- ^ How 'bout them toad suckers? Ain't they clods? Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Smoky Mountain News. Accessed on May 6, 2007

- PMID 16054186.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7890-2642-2.

- ^ S2CID 13153575.

- PMID 31061128.

- PMID 16455218.

- ^ Chamakura RP (1994). "Bufotenine—a hallucinogen in ancient snuff powders of South America and a drug of abuse on the streets of New York City". Forensic Sci Rev. 6 (1): 2–18.

- ]

- ISBN 978-0849301940.

- S2CID 23801665.

- ^ "South Korean man dies after eating toads". BBC. 21 April 2017.

- ^ "Taiwanese dies from eating toads, 5 injured". Taiwan News. 17 December 2019. Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- ^ PMID 13324106.

- PMID 13605329.

- S2CID 9578617.

- S2CID 5877023.

- S2CID 4192320.

- PMID 5860629.

- PMID 10350367.

- S2CID 20830063.

- PMID 1058643.

- ^ PMID 20150873.

- PMID 8747157.

- PMID 7749594.

- S2CID 33258299.

- ^ Criminal Code Regulation 2005 (SL2005-2) (rtf), Australian Capital Territory, May 1, 2005, retrieved 2007-08-12

- ^ Poisons Standard October 2015 https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2015L01534

- ^ Poisons Act 1964 Archived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine. slp.wa.gov.au

- ^ Misuse of Drugs Act 1981 (2015) Archived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine. slp.wa.gov.au

- ^ §1308.11 Schedule I. Archived 2009-08-27 at the Wayback Machine deadiversion.usdoj.gov

- ^ "Folkhälsomyndigheten föreslår att 20 ämnen klassas som narkotika eller hälsofarlig vara" (in Swedish). Folkhälsomyndigheten. 15 May 2019. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2019.