Bulgarians

българи bŭlgari | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| c. 9 million[1][2]

Torlak speakers in Serbia. | |

^ a: The 2011 census figure was 5,664,624.[46] The question on ethnicity was voluntary and 10% of the population did not declare any ethnicity,[47] thus the figure is considered an underestimation. Ethnic Bulgarians are estimated at around 6 million, 85% of the population.[48] ^ b: Estimates[49][50] of the number of Pomaks whom most scholars categorize as Bulgarians[51][52] ^ c: According to the 2002 census there were 1,417 Bulgarians in North Macedonia.[53] Between 2003 and 2017, according to the data provided by Bulgarian authorities some 87,483[54]-200,000[55] permanent residents of North Macedonia declared Bulgarian origin in their applications for Bulgarian citizenship, of which 67,355 requests were granted. A minor part of them are among the total of 2,934 North Macedonia-born residents, who are residing in Bulgaria by 2016.[56] ^ d: by citizenship excluding dual citizens ^ e: by single ethnic group per person ^ f: by foreign-born ^ h: by heritage ^ n: by legal nationality ^ m: by nationality, naturalisation and descendant background |

Bulgarians (

Etymology

Bulgarians derive their ethnonym from the Bulgars. Their name is not completely understood and difficult to trace back earlier than the 4th century AD,

Citizenship

According to art. 25(1) of

Ethnogenesis

Bulgarians are descended from peoples of vastly different origins and numbers, and are thus the result of a "melting pot" effect. The main ethnic elements which blended in to produce the modern Bulgarian ethnicity are:

- Early Slavs – an Indo-European group of tribes that migrated from Eastern Europe into the Balkans in the 6th–7th century CE and imposed their language and culture on the local Thracian, Roman and Greek communities. Approx. 40% of Bulgarian autosomal make-up comes from a northeastern European population that admixed with the native population in 400–1000 CE;[68][71]

- Bulgars – a semi-nomadic tribal federation from Central Asia that settled in the northeast of the Balkans in 7th century CE, federated with the local Slavic and Slavicized population, organised the early medieval Bulgarian statehood and bequeathed their ethnonym to the modern Bulgarian ethnicity, while eventually assimilating into the Slavic population.[72][73] Approximately 2.3% of Bulgarian genes originate in Central Asia, corresponding to Asian tribes such as the Bulgars, with admixture peaking in the 9th century CE;[74]

The indigenous Thracians left a cultural and genetic legacy.

The early Slavs emerged from their original homeland in the early 6th century, and spread to most of the eastern

The Bulgars are first mentioned in the 4th century in the vicinity of the

In the 670s, some Bulgar tribes, the Danube Bulgars led by

During the Early Byzantine Era, the Roman provincials in Scythia Minor and Moesia Secunda were already engaged in economic and social exchange with the 'barbarians' north of the Danube. This might have facilitated their eventual Slavonization,[104] although the majority of the population appears to have been withdrawn to the hinterland of Constantinople or Asia Minor prior to any permanent Slavic and Bulgar settlement south of the Danube.[105] The major port towns in Pontic Bulgaria remained Byzantine Greek in their outlook. The large scale population transfers and territorial expansions during the 8th and 9th century, additionally increased the number of the Slavs and Byzantine Christians within the state, making the Bulgars quite obviously a minority.[106] The establishment of a new state molded the various Slav, Bulgar and earlier or later populations into the "Bulgarian people" of the First Bulgarian Empire[73][107][108] speaking a South Slavic language.[109] In different periods to the ethnogenesis of the local population contributed also different Indo-European and Turkic people, who settled or lived on the Balkans.

Bulgarian ethnogenetic conception

The Bulgarians are usually regarded as part of the

Genetic origins

According to a triple analysis –

Bulgarians, like most Europeans, largely descend from three distinct lineages:

History

| Part of a series on |

| Bulgarians Българи |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| By country |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Other |

The First Bulgarian Empire was founded in 681. After the adoption of

In 1018, Bulgaria lost its independence and remained a Byzantine subject until 1185, when the

Some Bulgarians supported the Russian Army when they crossed the Danube in the middle of the 18th century. Russia worked to convince them to settle in areas recently conquered by it, especially in Bessarabia. As a consequence, many Bulgarian refugees settled there, and later they formed two military regiments, as part of the Russian military colonization of the area in 1759–1763.[142]

Bulgarian national movement

During the

It was not until the 1850s when the Bulgarians initiated a purposeful struggle against the

Eastern Rumelia was annexed to Bulgaria in 1885 through bloodless revolution. During the early 1890s, two pro-Bulgarian revolutionary organizations were founded: the

In the early 20th century the control over Macedonia became a key point of contention between Bulgaria, Greece, and

Demographics

Most Bulgarians live in

Associated ethnic groups

Bulgarians are considered most closely related to the

Culture

Language

Bulgarians speak a

Bulgarian demonstrates some linguistic developments that set it apart from other Slavic languages shared with

The Bulgarian language is spoken by the majority of the Bulgarian diaspora, but less so by the descendants of earlier emigrants to the U.S., Canada, Argentina and Brazil.

Bulgarian linguists consider the officialized Macedonian language (since 1944) to be a local codified variation of Bulgarian, just as most ethnographers and linguists until the early 20th century considered the local Slavic speech in the Macedonian region as Bulgarian dialects.[citation needed] The president of Bulgaria, Zhelyu Zhelev, declined to recognize Macedonian as a separate language when North Macedonia became a new independent state. The Bulgarian language is written in the Cyrillic script.

Cyrillic alphabet

In the first half of the 10th century, the

Name system

There are several different layers of Bulgarian names. The vast majority of them have either Christian (names like Lazar,

Most Bulgarian male surnames have an -ov

Other common Bulgarian male surnames have the -ev surname suffix (Cyrillic: -ев), for example Stoev, Ganchev, Peev, and so on. The female surname in this case would have the -eva surname suffix (Cyrillic: -ева), for example: Galina Stoeva. The last name of the entire family then would have the plural form of -evi (Cyrillic: -еви), for example: the Stoevi family (Стоеви).

Another typical Bulgarian surname suffix, though less common, is -ski. This surname ending also gets an –a when the bearer of the name is female (Smirnenski becomes Smirnenska). The plural form of the surname suffix -ski is still -ski, e.g. the Smirnenski family (Смирненски).

The ending –in (female -ina) also appears rarely. It used to be given to the child of an unmarried woman (for example the son of Kuna will get the surname Kunin and the son of Gana – Ganin). The surname suffix -ich can be found only occasionally, primarily among the Roman Catholic Bulgarians. The surname ending –ich does not get an additional –a if the bearer of the name is female.

Religion

Most Bulgarians are at least nominally members of the

Despite the position of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church as a unifying symbol for all Bulgarians, small groups of Bulgarians have converted to other faiths through the course of time. During Ottoman rule, a substantial number of Bulgarians converted to Islam, forming the community of the

Art and science

Boris Christoff, Nicolai Ghiaurov, Raina Kabaivanska and Ghena Dimitrova made a precious contribution to opera singing with Ghiaurov and Christoff being two of the greatest bassos in the post-war period. Similarly, Anna-Maria Ravnopolska-Dean is one of the best-known harpists today. Bulgarians have made valuable contributions to world culture in modern times as well.

Bulgarians in the diaspora have also been active. American scientists and inventors of Bulgarian descent include

Cuisine

Famous for its rich salads required at every meal, Bulgarian cuisine is also noted for the diversity and quality of

Most Bulgarian dishes are oven baked, steamed, or in the form of stew. Deep-frying is not very typical, but grilling—especially different kinds of meats—is very common. Pork meat is the most common meat in the Bulgarian cuisine. Oriental dishes do exist in Bulgarian cuisine with most common being

Folk beliefs and customs

Bulgarians may celebrate Saint Theodore's Day with horse racings. At Christmas Eve a Pogača with fortunes is cooked, which are afterwards put under the pillow. At Easter the first egg is painted red and is kept for a whole year. On the Baptism of Jesus a competition to catch the cross in the river is held and is believed the sky is "opened" and any wish will be fulfilled.

Bulgarians as well as

Bulgarian mythology and fairy tales are mainly about forest figures, such as the dragon zmey, the nymphs samovili (samodivi), the witch veshtitsa. They are usually harmful and devastating, but can also help the people. The samovili are said to live in beeches and sycamores the, which are therefore considered holy and not permitted burning.

Despite eastern Ottoman influence is obvious in areas such as cuisine and music, Bulgarian folk beliefs and mythology seem to lack analogies with

Folk dress and music

Bulgarian folk costumes feature long white robes, usually with red embrdoiery and ornaments derived from the Slavic Rachenik. The costume is considered to be mainly derived from the dress of the

Folk songs are most often about the nymphs from Bulgarian and

Valya Balkanska is a folk singer thanks to whom the Bulgarian speech in her song "Izlel ye Delyo Haydutin" will be played in the Outer space for at least 60,000 years more as part of the Voyager Golden Record selection of music included in the two Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977.

Sport

As for most European peoples,

In the beginning of the 20th century Bulgaria was famous for two of the best wrestlers in the world –

Symbols

The national symbols of the Bulgarians are the

The national flag of Bulgaria is a rectangle with three colours: white, green, and red, positioned horizontally top to bottom. The colour fields are of same form and equal size. It is generally known that the white represents – the sky, the green – the forest and nature and the red – the blood of the people, referencing the strong bond of the nation through all the wars and revolutions that have shaken the country in the past. The Coat of arms of Bulgaria is a state symbol of the sovereignty and independence of the Bulgarian people and state. It represents a crowned rampant golden lion on a dark red background with the shape of a shield. Above the shield there is a crown modeled after the crowns of the emperors of the Second Bulgarian Empire, with five crosses and an additional cross on top. Two crowned rampant golden lions hold the shield from both sides, facing it. They stand upon two crossed oak branches with acorns, which symbolize the power and the longevity of the Bulgarian state. Under the shield, there is a white band lined with the three national colours. The band is placed across the ends of the branches and the phrase "Unity Makes Strength" is inscribed on it.

Both the Bulgarian flag and the Coat of Arms are also used as symbols of various Bulgarian organisations, political parties and institutions.

The horse of the

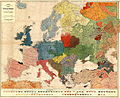

Maps

-

Map of A. Scobel, Andrees Allgemeiner Handatlas, 1908

-

Distribution of the Balkan peoples in 1911, Encyclopædia Britannica

-

Ethnic groups in the Balkans and Asia Minor byWilliam R. Shepherd, 1911

-

Distribution of European peoples in 1914 according to L. Ravenstein

-

Swiss ethnographic map of Europe published in 1918 by Juozas Gabrys

-

Distribution of Bulgarians in Odesa Oblast, Ukraine according to the 2001 census

-

Distribution of Bulgarians by first language in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Ukraine according to the 2001 census

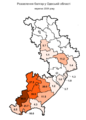

-

Distribution of predominant ethnic groups in Bulgaria according to the 2011 census

-

Distribution of Bulgarians in Romania according to the 2002 census

-

Distribution of Bulgarians in Moldova according to the 2004 census

Historiography

With the formation of the Bulgarian ethnicity in the mid-10th century,[187][188] the Byzantines usually called the Bulgarians Moesi, and their lands, Moesia.[189]

See also

References

- ISBN 9781317464006. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ ISBN 9781598843033. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ Етнокултурни характеристики на населението към 7 септември 2021 година, НСИ.

- ^ "Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit – Ausländische Bevölkerung, Ergebnisse des Ausländerzentralregisters (2020)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ^ "Ukrainian 2001 census". ukrcensus.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- ^ "Bulgarians in Ukraine". Bulgarian Parliament (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "Идва ли краят на изнасянето от България?". 24chasa.bg (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "TablaPx". Ine.es. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ISBN 9783865965202. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ISBN 9781452276267. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "Population of the UK by country of birth and nationality – Office for National Statistics". Ons.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 26 December 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "National Bureau of Statistics // Population Census 2004". Statistica.md. 30 September 2009. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ De acordo com dados do Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), cerca de 62.000 brasileiros declararam possuir ascendência búlgara no ano de 2006, o que faz com que o país abrigue a nona maior colônia búlgara do mundo.

- ^ "bTV – estimate for Bulgarians in Brazil" (in Bulgarian). btv.bg. Archived from the original on 11 October 2010.

- ^ a b c "World Migration". International Organization for Migration. 15 January 2015. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ a b "3 млн. българи са напуснали страната за последните 23 години". bTV, quote of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria – Bulgarians in Argentina". Mfa.bg (in Bulgarian). Retrieved 29 April 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Италианските българи". 24 Chasa (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on 6 February 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ "Statistiche demografiche ISTAT". demo.istat.it. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ "Bevolking; geslacht, leeftijd, generatie en migratieachtergrond, 1 januari" (in Dutch). Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). 22 July 2021. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". Statistics Canada. 8 May 2013. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "International Migration Outlook 2016 – OECD READ edition". OECD iLibrary. Archived from the original on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ "Министерство на външните работи". Archived from the original on 23 July 2010.

- ISBN 9783865965202. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ STATISTIK AUSTRIA. "Bevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeit und Geburtsland". Statistik.at. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ "Russia 2010 census" (XLS). Gks.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 30 April 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ "Cypriot 2011 census". Cystat.gov.cy. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ^ "Serbian 2022 census". Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Archived from the original on 8 June 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Foreigners by category of residence, sex, and citizenship as of 31 December 2016". Czech Statistical Office. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ^ "Population by country of origin". statbank.dk. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ^ "Utrikes födda efter födelseland, kön och år". Scb.se. Statistiska Centralbyrån. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ "Many new Syrian immigrants". Ssb.no. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ statistique, Office fédéral de la. "Population". Bfs.admin.ch (in French). Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ "National Institute of Statistics of Portugal – Foreigners in 2013" (PDF). Sefstat.sef.pt (in Portuguese). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ^ "Bulgaria's State Agency for Bulgarians Abroad – Study about the number of Bulgarian immigrants as of 03.2011". Aba.government.bg (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on 11 January 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "Romanian 2011 census" (PDF). Edrc.ro (in Romanian). Archived from the original (XLS) on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ^ "Australian 2011 census" (PDF). Abs.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Bespyatov, Tim. "Ethnic composition of Kazakhstan 2023 (based on 2021 census)". Pop-stat.

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria – Bulgarians in South Africa". Mfa.bg (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ISBN 978-963-235-542-9. Archived(PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ "Väestö 31.12. Muuttujina Maakunta, Kieli, Ikä, Sukupuoli, Vuosi ja Tiedot". Archived from the original on 7 April 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ "SODB2021 - Obyvatelia - Základné výsledky". www.scitanie.sk. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "SODB2021 - Obyvatelia - Základné výsledky". www.scitanie.sk. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ ISBN 9780203403747. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Bulgarian 2011 census" (PDF) (in Bulgarian). nsi.bg. p. 25. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ "EPC 2014". Epc2014.princeton.edu. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ Свободно време (27 July 2011). "Експерти по демография оспориха преброяването | Dnes.bg Новини". Dnes.bg. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-55671-159-6. Archivedfrom the original on 29 November 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ^ "Türkiye'deki Kürtlerin sayısı!" (in Turkish). 6 June 2008. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ISBN 9780739107577.

Most scholars categorize Pomaks as "Slav Bulgarians...

- ISBN 9780946690718. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

...'Pomaks', are a religious minority. They are Slav Bulgarians who speak Bulgarian...

- ^ "Republic of North Macedonia - State Statistical Office". 3 July 2010. Archived from the original on 3 July 2010.

- ^ "Новите българи". Capital.bg (in Bulgarian). 21 April 2017. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "Јончев: Над 200.000 Македонци чекаат бугарски пасоши". МКД.мк (in Macedonian). Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Perspectives migrations internationales 2016 et Eurostat.

- ISBN 9780313309847. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-472-08149-3. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ISBN 978-963-7326-60-8. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Gurov, Dilian (March 2007). "The Origins of the Bulgars" (PDF). p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ISBN 0-674-51173-5.

- ^ Karataty, Osman. In Search of the Lost Tribe: the Origins and Making of the Croatian Nation Archived 28 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine, p. 28.

- ^ "Народно събрание на Република България – Конституция". Parliament.bg. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "Преброяване 2021: Етнокултурна характеристика на населението" [2021 Census: Ethnocultural characteristics of the population] (PDF). National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 November 2022.

- ^ ISBN 0-89158-530-3, p. 27.

- ^ PMID 26332464.

- ^ "A detailed analysis is made of the assimilation process which took place between Slavs and Thracians. It ended in the triumph of the Slav element and in the ultimate disappearance of the Thracian ethnos...Attention is drawn to the fact that even though assimilated, the Thracian ethnicon left behind traces of its existence (in toponymy, the lexical wealth of the Bulgarian language, religious beliefs, material culture, etc.) which should be extensively studied in all their aspects in the future..." For more see: Димитър Ангелов, Образуване на българската народност, (Издателство Наука и изкуство, "Векове", София, 1971) pp. 409–410. (Summary in Englis Archived 28 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine h).

- ^ PMID 24531965.

- ^ "Companion website for "A genetic atlas of human admixture history", Hellenthal et al, Science (2014)". A genetic atlas of human admixture history. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- PMID 24531965.

- ^ "Bulgar – people". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0472081493. Archivedfrom the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ Science, 14 February 2014, Vol. 343 no. 6172, p. 751, A Genetic Atlas of Human Admixture History, Garrett Hellenthal at al.: " CIs. for the admixture time(s) overlap but predate the Mongol empire, with estimates from 440 to 1080 CE (Fig.3. Archived 27 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "The so-called Bulgar inscriptions are, with few exceptions, written in Greek rather than in Turkic runes; they mention officials with late antique titles, and use late Antique terminology and indictional dating. Contemporary Byzantine inscriptions are not obviously similar, implying that this (Bulgar) epigraphic habit was not imported from Constantinople but was a local Bulgar development, or rather, it was an indigenous 'Roman' inheritance." Nicopolis ad Istrium: Backward and Balkan, by M Whittow.

- ^ Bulgarian historical review, Publishing House of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, pp. 53

- ^ The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, 7th edition, pp. 57

- ^ Ethnic Continuity in the Carpatho-Danubian Area, Elemér Illyés

- ISBN 9781884964985.

- ^ Liviu Petculescu. "The Roman Army as a Factor of Romanisation in the North-Eastern Part of Moesia Inferior" (PDF). Pontos.dk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ISBN 9781840146172. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ISBN 9789004252585. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Sofia – 127 years capital. Sofia Municipality

- ^ Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, by Douglas Q. Adams, pp. 576

- ISBN 0-472-08149-7, p. 31

- ^ ISBN 1-4039-6417-3

- ^ Образуване на българската държава. проф. Петър Петров (Издателство Наука и изкуство, София, 1981)

- ^ "Образуване на българската народност.проф. Димитър Ангелов (Издателство Наука и изкуство, "Векове", София, 1971)". Kroraina.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Runciman, Steven. 1930. A history of the First Bulgarian Empire Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. London: G. Bell & Sons.: §I.1 Archived 28 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Vassil Karloukovski. "История на българската държава през средните векове Васил Н. Златарски (I изд. София 1918; II изд., Наука и изкуство, София 1970, под ред. на проф. Петър Хр. Петров)". Kroraina.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Rasho Rashev, Die Protobulgaren im 5.-7. Jahrhundert, Orbel, Sofia, 2005. (in Bulgarian, German summary)

- JSTOR 23658601.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Dobrev, Petar. "Езикът на Аспаруховите и Куберовите българи". 1995. (in Bulgarian)

- ^ Bakalov, Georgi. Малко известни факти от историята на древните българи. Part 1 Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine & Part 2 Archived 1 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. (in Bulgarian)

- ^ Йорданов, Стефан. Славяни, тюрки и индо-иранци в ранното средновековие: езикови проблеми на българския етногенезис. В: Българистични проучвания. 8. Актуални проблеми на българистиката и славистиката. Седма международна научна сесия. Велико Търново, 22–23 август 2001 г. Велико Търново, 2002, 275–295.

- ^ Надпис № 21 от българското златно съкровище "Наги Сент-Миклош", студия от проф. д-р Иван Калчев Добрев от Сборник с материали от Научна конференция на ВА "Г. С. Раковски". София, 2005 г.

- ISBN 9789052012971. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ Cristian Emilian Ghita, Claudia Florentina Dobre (2016). Quest for a Suitable Past: Myths and Memory in Central and Eastern Europe. p. 142.

- ISBN 9780312299132.

- ^ Komatina 2010, p. 55–82.

- ^ Steven Runciman, A history of the First Bulgarian Empire, page 28

- ISBN 978-9004125247. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Florin Curta. Horsemen in forts or peasants in villages? Remarks on the archaeology of warfare in the 6th to 7th century Balkansmore; 2013.

- ISBN 9780521291262. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "The Formation of the Bulgarian Nation, Academician Dimitŭr Simeonov Angelov, Summary, Sofia-Press, 1978". Kroraina.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ L. Ivanov. Essential History of Bulgaria in Seven Pages. Sofia, 2007.

- ISBN 9780313309847. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-472-08149-3. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ISBN 978-963-7326-60-8. Archivedfrom the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ISBN 978-3-319-45108-4.

- ^ "Differentiation in Entanglement: Debates on Antiquity, Ethnogenesis and Identity in Nineteenth-Century Bulgaria", in Klaniczay, Gábor and Werner, Michael (eds.), Multiple Antiquities – Multiple Modernities. Ancient Histories in Nineteenth Century European Cultures. Frankfurt – Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011, 213–246.

- ISBN 9639776289.

- ISBN 0230583474, p. 285.

- ISBN 1442241802, pp. 189–190.

- ISBN 9789004290365, pp 10–117.

- ISBN 9546171212, pp. 7–11.

- ^ Александър Николов, "Параисторията като феномен на прехода: преоткриването на древните българи" в "Историческият хабитус: опредметената история", 2013, съст. Ю. Тодоров и А. Лунин, стр. 24–63.

- ^ "Companion website for "A genetic atlas of human admixture history", Hellenthal et al, Science (2014)". A genetic atlas of human admixture history.

Hellenthal, Garrett; Busby, George B.J.; Band, Gavin; Wilson, James F.; Capelli, Cristian; Falush, Daniel; Myers, Simon (14 February 2014). "A Genetic Atlas of Human Admixture History".PMID 24531965.

Hellenthal, G.; Busby, G. B.; Band, G.; Wilson, J. F.; Capelli, C.; Falush, D.; Myers, S. (2014). "Supplementary Material for "A genetic atlas of human admixture history"". Science. 343 (6172): 747–751.PMID 24531965.S7.6 "East Europe": The difference between the 'East Europe I' and 'East Europe II' analyses is that the latter analysis included the Polish as a potential donor population. The Polish were included in this analysis to reflect a Slavic language speaking source group." "We speculate that the second event seen in our six Eastern Europe populations between northern European and southern European ancestral sources may correspond to the expansion of Slavic language speaking groups (commonly referred to as the Slavic expansion) across this region at a similar time, perhaps related to displacement caused by the Eurasian steppe invaders (38; 58). Under this scenario, the northerly source in the second event might represent DNA from Slavic-speaking migrants (sampled Slavic-speaking groups are excluded from being donors in the EastEurope I analysis). To test consistency with this, we repainted these populations adding the Polish as a single Slavic-speaking donor group ("East Europe II" analysis; see Note S7.6) and, in doing so, they largely replaced the original North European component (Figure S21), although we note that two nearby populations, Belarus and Lithuania, are equally often inferred as sources in our original analysis (Table S12). Outside these six populations, an admixture event at the same time (910CE, 95% CI:720-1140CE) is seen in the southerly neighboring Greeks, between sources represented by multiple neighboring Mediterranean peoples (63%) and the Polish (37%), suggesting a strong and early impact of the Slavic expansions in Greece, a subject of recent debate (37). These shared signals we find across East European groups could explain a recent observation of an excess of IBD sharing among similar groups, including Greece, that was dated to a wide range between 1,000 and 2,000 years ago (37)

- ^ PMID 25731166.

- PMID 36859578.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (21 February 2017). "Thousands of horsemen may have swept into Bronze Age Europe, transforming the local population". Science. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ISBN 9780521815390. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-85065-534-3.

- ISBN 978-9989756078. Archivedfrom the original on 15 September 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ISBN 9780719060953. Archivedfrom the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ISBN 978-0472081493. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2015 – via Books.google.bg.

- ISBN 9780295800646. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Bulgaria – Ottoman rule". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 2 January 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

With the capture of a rump Bulgarian kingdom centred at Bdin (Vidin) in 1396, the last remnant of Bulgarian independence disappeared. ... The Bulgarian nobility was destroyed—its members either perished, fled, or accepted Islam and Turkicization—and the peasantry was enserfed to Turkish masters.

- ISBN 978-9004135765. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ISBN 9789052013749. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ISBN 978-9004121010. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ISBN 0195374924, p. 276: "There were almost no remnants of a Bulgarian ethnic identity; the population defined itself as Christians, according to the Ottoman system of millets, that is, communities of religious beliefs. The first attempts to define a Bulgarian ethnicity started at the beginning of the 19th century."

- ISBN 978-0313319495. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ]

- ISBN 9780521273237. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ISBN 9788884924643. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ]

- ^ Milchev, Vladimir (2002). "Два хусарски полка с българско участие в системата на държавната военна колонизация в Южна Украйна (1759-1762/63 г.)" [Two Hussar Regiments with Bulgarian Participation in the System of the State Military Colonization in Southern Ukraine (1759-1762/63)]. Исторически преглед (in Bulgarian) (5–6): 154–65. Archived from the original on 31 December 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ISBN 9780295803609. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ISBN 978-3825813871.

- ISBN 0847698092, p. 236.

- ISBN 978-1-85065-492-6. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-691-04356-2. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-8014-8736-1.

The key fact about Macedonian nationalism is that it is new: in the early twentieth century, Macedonian villagers defined their identity religiously—they were either "Bulgarian," "Serbian," or "Greek" depending on the affiliation of the village priest. While Bulgarian was most common affiliation then, mistreatment by occupying Bulgarian troops during WWII cured most Macedonians from their pro-Bulgarian sympathies, leaving them embracing the new Macedonian identity promoted by the Tito regime after the war.

- ^ "Experts for Census 2011" (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ a b "Bulgarian 2001 census" (in Bulgarian). nsi.bg. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ "Chairman of Bulgaria's State Agency for Bulgarians Abroad – 3–4 million Bulgarians abroad in 2009" (in Bulgarian). 2009. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ^ "Божидар Димитров преброи 4 млн. българи зад граница" (in Bulgarian). 2010. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ISBN 9781850654926. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ISBN 1-85065-238-4, p. 109.

- ^ Felix Philipp Kanitz, (Das Konigreich Serbien und das Serbenvolk von der Romerzeit bis dur Gegenwart, 1904, in two volume) # "In this time (1872) they (the inhabitants of Pirot) did not presume that six years later the often damn Turkish rule in their town will be finished, and at least they did not presume that they will be include in Serbia, because 'they always feel that they are Bulgarians'. ("Србија, земља и становништво од римског доба до краја XIX века", Друга књига, Београд 1986, p. 215)"And today (in the end of the 19th century) among the older generation there are many fondness to Bulgarians, that it led him to collision with Serbian government. Some hesitation can be noticed among the youngs..." ("Србија, земља и становништво од римског доба до краја XIX века", Друга књига, Београд 1986, c. 218; Serbia – its land and inhabitants, Belgrade 1986, p. 218)

- ISBN 9789545293672.) It describes a population in Nish sandjak as Bulgarian, see: [1] Archived 5 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Стойков, Стойко: Българска диалектология, Акад. изд. "Проф. Марин Дринов", 2006.

- ^ Girdenis A., Maziulis V. Baltu kalbu divercencine chronologija // Baltistica. T. XXVII (2). – Vilnius, 1994. – P. 9.

- ^ "Топоров В.Н. Прусский язык. Словарь. А – D. – М., 1975. – С. 5". S7.hostingkartinok.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ISBN 9781137048172

- ^ a b "Преброяване 2021: Етнокултурна характеристика на населението" [2021 Census: Ethnocultural characteristics of the population] (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 November 2022.

- ^ staff, The Sofia Globe (24 November 2022). "Census 2021: Close to 72% of Bulgarians say they are Christians". The Sofia Globe. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "71.5% are the Christians in Bulgaria - Novinite.com - Sofia News Agency". www.novinite.com. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ "Social Construction of Identities: Pomaks in Bulgaria, Ali Eminov, JEMIE 6 (2007) 2 © 2007 by European Centre for Minority Issues" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ От Труд онлайн. "Архивът е в процес на прехвърляне – Труд". Trud.bg. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ISBN 9781438109183. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ISBN 9780813800325. Archivedfrom the original on 28 September 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "Bulgaria Poultry and Products Meat Market Update". The Poultry Site. 8 May 2006. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ Колева Т. А. Болгары // Календарные обычаи и обряды в странах зарубежной Европы. Конец XIX — начало XX в. Весенние праздники. — М.: Наука, 1977. — С. 274–295. — 360 с.

- ^ "??" (PDF). Tangrabg.files.wordpress.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ a b "??" (PDF). Bkks.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ISBN 954-304-009-5

- ^ История во кратце о болгарском народе словенском

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y "??" (PDF). Mling.ru. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "Русалии – древните български обичаи по Коледа". Bgnow.eu. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Следи от бита и езика на прабългарите в нашата народна култура, Иван Коев, София, 1971.

- ^ ISBN 9781853024856.

The so-called Kapantsi - an ethnographic group living mainly in the Razgrad and Turgovishte, area of north-east Bulgaria - are believed to be descendants of Asparuh's Bulgars who have maintained at least something of their original heritage...the traditional costumes of Bulgaria are derived mainly from the ancient Slav costumes...Women's costumes fall into four main categories: one-apron, two-apron, sukman and saya. Like men's costumes, these are not intrinsically separate types, but have evolved from the original chemise and apron worn by the early Slavs...Directly descended with little mutation from the dress of the ancient Slavs, the one-apron ...

- ^ "Д. Ангелов, Образуване на българската народност – 4.3". Promacedonia.org. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "Ekip7 Разград – Коренните жители на Разград и района – българи, ама не какви да е, а капанци!". Ekip7.bg. 14 September 2015. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "Значение узоров и орнаментов – Русские орнаменты и узоры" [The meaning of patterns and ornaments]. Russian ornaments and patterns. 21 November 2013. Archived from the original on 21 November 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ "Символы в орнаментах древних славян". Etnoxata.com.ua. 25 January 2015. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ В. В. Якжик, Государственный флаг Республики Беларусь, w: Рекомендации по использованию государственной символики в учреждениях образования, page 3.

- ISBN 9781847883988.

Bulgarian women's dress include overgarments that are joined at the shoulders and are considered to have evolved from the sarafan. (the pinafore dress typically worn by women of various Slav nations). This type of garment includes the soukman and the saya and aprons that fasten at the waist that are also attributed to a Slavic origin.

- ^ "HRISTO STOICHKOV | FCBarcelona.cat". Fcbarcelona.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ISBN 9781582618173. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-521-61637-9.

- ISBN 978-0472081493.

- ISBN 9004409939.

Sources

- Komatina, Predrag (2010). "The Slavs of the mid-Danube basin and the Bulgarian expansion in the first half of the 9th century" (PDF). Зборник радова Византолошког института. 47: 55–82.

- ISBN 9780351176449.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

External links

Media related to Bulgarians at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bulgarians at Wikimedia Commons