Burmese amber

Burmese amber, also known as Burmite or Kachin amber, is

Geological context, depositional environment and age

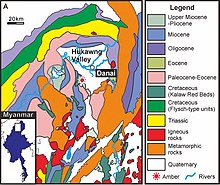

The amber is found within the Hukawng Basin, a large Cretaceous-

At Noije Bum, located on a ridge, amber is found within fine grained

Paleoenvironment

The Burmese amber paleoforest is considered to have been a

The amber itself is primarily disc-shaped and flattened along the

Fauna and flora

The list of taxa is extraordinarily diverse, with 50 classes (or equivalent), 133 orders (or equivalent), 726 families, 1,757 genera and 2,770 species described as of 2023. The vast majority of the species are arthropods, mostly insects.[16]

Arthropods

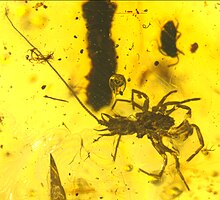

Over 2500 species of arthropods (with over 2000 of these species beings insects) are known from the deposit,

Other invertebrates

A wide variety of other invertebrates have been reported. These include

Vertebrates

Only a handful of vertebrates have been described from Burmese amber, these include the

Flora

A wide variety of plants have been reported from the deposit. These include

Other

A number of fungi species have been reported, as well as various microorganisms.[16]

History

The amber is apparently referred to in ancient Chinese sources as originating from

History of research

While a 1892 study considered the amber likely to be

Modern exploitation and controversy

Leeward Capital Corp, a small Canadian mining firm, controlled the deposit from the mid-1990s to c. 2000, though the history of exploitation during the 2000s is obscure. The Kachin Independence Army (KIA), an armed rebel group seeking to secede Kachin province from Myanmar, controlled the area during the early to mid 2010's. During the early 2010s, production rapidly increased. The working conditions at the mines have been described as extremely unsafe, down 100 m (330 ft) deep pits barely wide enough to crawl through, with no accident compensation.[7] The KIA controlled amber export via numerous licenses, taxes, restrictions on movement of labor, and enforced auctions.[38] The main amber market in Myanmar is Myitkyina. Most amber is smuggled into China, primarily for jewelry, with estimates of around 100 tonnes passing through to the main market of Tengchong, Yunnan in 2015, with a then estimated value between five and seven billion yuan. Burmese amber was estimated to make up 30% of Tenchong's gemstone market (the rest being Myanmar Jade), and was declared one of the city's eight main industries by the local government.[39] The presence of calcite veins are a major factor in determining the gem quality of pieces, with pieces with a large number of veins having significantly lower value.[5] In June 2017 the Tatmadaw seized control of the mines from the KIA.[40]

Sales of amber were alleged to help fund the Kachin conflict by various news organisations in 2019.[41][42] Interest in this discussion rose in March 2020 after the highly publicised description of Oculudentavis, which made the cover of Nature.[43] On April 21, 2020, the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP) published a letter of recommendation to journal editors asking for “a moratorium on publication for any fossil specimens purchased from sources in Myanmar after June 2017 when the Myanmar military began its campaign to seize control of the amber mining”.[44] On April 23, 2020 Acta Palaeontologica Polonica stated that it would not accept papers on Burmese amber material collected from 2017 onwards, after the Burmese military took control of the deposit, requiring "certification or other demonstrable evidence, that they were acquired before the date both legally and ethically".[45] On May 13, 2020, the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology published an editorial stating that it would no longer consider papers based whole or in part on Burmese amber material, regardless of whether in historic collections or not.[46] On 30 June 2020, a statement from the International Palaeoentomological Society was published in response to the SVP, criticising the proposal to ban publishing on Burmese amber material.[47] In August 2020, a comment from over 50 authors was published in PalZ responding to the SVP statement. The authors disagreed with the proposal of a moratorium, describing the focus on the Burmese amber as "arbitrary" and that "The SVP’s recommendation for a moratorium on Burmese amber affects fossil non-vertebrate research much more than fossil vertebrate research and clearly does not represent this part of the palaeontological community."[48]

The conclusion that Burmese amber funded the Tatmadaw was disputed by

Other Myanmar ambers

Other deposits of amber are known from several regions in Myanmar, with noted deposits in the Shwebo District of the Sagaing Region, from the Pakokku and Thayet districts of Magway Region and the Bago District of the Bago Region.[50][36]

Tilin amber

A 2018 study on an amber deposit from

Hkamti amber

The Hkamti site is located ca. 90 km southwest of the Angbamo site and predominantly consists of limestone, interbedded with mudstone and

See also

References

- .

- S2CID 90373037.

- S2CID 240162578.

- PMID 31579400.

- ^ .

- .

- ^ S2CID 194317225.

- ^ S2CID 224899464.

- PMID 31085633.

- S2CID 68048811.

- S2CID 204250232.

- PMID 33758318.

- S2CID 246443363.

- ^ Poinar, G.; Lambert, J.B.; Wu, Y. (2007-08-10). "Araucarian source of fossiliferous Burmese amber: Spectroscopic and anatomical evidence". Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas. 1: 449–455.

- .

- ^ ISSN 3021-1867.

- S2CID 14816297.

- S2CID 202899476.

- ISSN 2624-2834.

- S2CID 250148030.

- S2CID 247227499.

- S2CID 239420481.

- S2CID 253637881.

- .

- PMID 38320551.

- PMID 34478185.

- PMID 27693140.

- .

- ^ ISSN 2707-9783.

- PMID 34129826.

- PMID 30035227.

- PMID 27939315.

- S2CID 195261188.

- ^ a b c d Zherikhin, V.V., Ross, A.J., 2000. A review of the history, geology and age of Burmese amber (Burmite). Bulletin of the Natural History Museum, London (Geology) 56 (1), 3–10.

- ^ a b Pemberton, R. B. (1837). "Abstract of the Journal of a route travelled by Cap. Hannay from the Capital of Ava to the Amber Mines of the Hukong valley in the South east frontier of Assam". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 64: 248–278.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-9558636-4-6.

- ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ S2CID 235174183.

- ISSN 2051-364X.

- ^ Lawton, Graham. "Blood amber: The exquisite trove of fossils fuelling war in Myanmar". New Scientist. Retrieved 2020-02-04.

- ISSN 1072-7825. Retrieved 2020-02-04.

- ^ Lawton, Graham. "Military now controls Myanmar's scientifically important amber mines". New Scientist. Retrieved 2020-02-04.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-03-13.

- ^ Rayfield, Emily J.; Theodor, Jessica M.; Polly, P. David (2020). Fossils from conflict zones and reproducibility of fossil-based scientific data. Society for Vertebrate Paleontology. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

- ^ "News - Acta Palaeontologica Polonica". www.app.pan.pl. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ISSN 1477-2019.

- ISSN 2624-2834.

- ISSN 0031-0220.

- .

- ^ Zherikhin, V. V.; Ross, A. J. (2000). "A review of the history, geology and age of Burmese amber burmite". Bulletin of the Natural History Museum, Geology Series.

- PMID 30093646.

- PMID 35102237.