c-Met inhibitor

c-Met inhibitors are a class of

Many c-Met inhibitors are currently[

c-Met stimulates cell scattering, invasion, protection from

History

Early in the 1980s MET was described as the protein product of a transforming oncogene.[9] [10]

Initial attempts to identify ATP-competitive c-Met inhibitors in 2002 led to the discovery of K252a, a staurosporine-like inhibitor which blocks c-Met.[10][11] K252a was the first structure to be solved in complex with the unphosphorylated MET kinase domain. It forms two

Later, series of more selective c-Met inhibitors were designed, where an indolin-2-one core (encircled in figure 1) was present in several kinase inhibitors. SU-11274 was evolved by substitution at the 5-position of the indolinone [9] and by adding a 3,5-dimethyl pyrrole group, PHA-665752 was evolved [11] – a second-generation inhibitor with better potency and activity.[10]

Interest in this field has risen rapidly since 2007 and over 70 patent applications had been published in mid-2009.[10]

Intensive efforts have been exerted in the

Introduction

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are a vital element in regulating many

c-Met dysregulation can be due to overexpression, gene amplification,

or small molecules inhibitors.[10]Structure and function

The c-Met RTK subfamily is different in structure to many other RTK families: The mature form has an extracellular α-chain (50kDa) and a transmembrane β-chain (140kDa) that are linked together by a disulfide bond. The beta chain contains the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain and a tail on the C-terminal which is vital for the docking of

HGF is the natural high-affinity ligand for Met.

Phosphorylation occurs in tyrosines close to the C-terminus, creating a multi-functional docking site[10][18] which recruits adaptor proteins and leads to downstream signalling. The signaling is mediated by Ras/Mapk, PI3K/Akt, c-Src and STAT3/5 and include cell proliferation, reduced apoptosis, altered cytoskeletal function and more.

The kinase domain usually consists of a bi-lobed structure, where the lobes are connected with a hinge region, adjacent to the very conserved ATP binding site.[10]

Development

Using information from the co-crystal structure of PHA-66752 and c-Met, the selective inhibitor PF-2341066 was designed. It was undergoing Phase I/II clinical trials in 2010. Changing a series of 4-phenoxyquinoline compounds with an

AM7 and SU11274 offered the first proof that relatively selective c-Met inhibitors could be identified and that the inhibition leads to an anti-tumour effect in vivo. When the co-crystal structures of AM7 and SU11274 with c-Met were compared, they were found to be different: SU-11274 binds adjacent to the hinge region with a U-shaped conformation; but AM7 binds to c-Met in an extended conformation which spans the area from the hinge region to the C-helix. It then binds in a hydrophobic pocket. c-Met assumes an inactive, unphosphorylated conformation with AM7, which can bind to both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated conformations of the kinase.[20]

Due to these two different types of binding, small molecule Met inhibitors have been divided into two classes; class I (SU-11274-like) and class II (AM7-like).[20] There is however another type of small-molecule inhibitors, which does not fit into either of the two classes; a non-competitive ATP inhibitor that binds in a different way to the other two.[21]

The small molecule inhibitors vary in selectivity, are either very specific or have a broad selectivity. They are either ATP competitive or non-competitive.[12]

ATP-competitive small molecule c-Met inhibitors

Even though the two classes are structurally different, they do share some properties: They both bind at the kinase hinge region (although they occupy different parts of the c-Met active site[20]) and they all aim to mimic the purine of ATP. BMS-777607 and PF-02341066 have a 2-amino-pyridine group, AMG-458 has a quinoline group and MK-2461 has a tricyclic aromatic group.[22]

Class I

Class I inhibitors have many different structures,

Structure-activity relationship of Class I inhibitors

A series of triazolotriazines was discovered, which showed great promise as a c-MET inhibitors.

Examples of Class I inhibitors

JNJ-38877605, which contains a difluoro methyl linker and a bioavailable quinoline group, was undergoing clinical trials of Phase I for advanced and refractory solid tumours in 2010.[12] The trial was terminated early due to renal toxicity caused by metabolites of the agent.[23][24]

PF-04217903, an ATP-competitive and exceptionally selective compound, has an N-hydroxyethyl pyrazole group tethered to C-7 of the triazolopyrazine. It was undergoing phase I clinical trials in 2010.[12] [needs update]

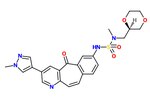

The SAR of the unique kinase inhibitor scaffold with powerful c-Met inhibitory activity, MK-2461, has been explored.[25] The pyridine nitrogen is necessary for inhibition activity and central ring saturation reduced potency.[12] Planarity of the molecule has proven to be essential for maximum potency.[25] Cyclic ethers balance acceptable cell-based activities and pharmacokinetic characteristics. The following elements are thought to be key in the optimization process:

1)

2) The tight SAR upon the addition of a

3) The relatively flat SAR of solvent-exposed groups.

Often, oncogenic mutations of c-Met cause a resistance to small molecule inhibitors. An MK-2461 analog was therefore tested against a variety of c-Met mutants but proved to be no less potent against them. This gives the molecule a big advantage as a treatment for tumours caused by c-Met dysregulation.[25] MK-2461 was undergoing phase I dose escalation trials in 2010.[12] [needs update]

Class II

Class II inhibitors are usually not as selective as those of class I.[10] Urea groups are also a common feature of class II inhibitors, either in cyclic or acyclic forms. Class II of inhibitors contains a number of different molecules, a common scaffold of which can be seen in figure 4.[12]

Structure-activity relationship of Class II inhibitors

Series of quinoline c-Met inhibitors with an acylthiourea linkage have been explored. Multiple series of analogs have been found with alternative hinge binding groups (e.g. replacement of the quinoline group), replacement of the thiourea linkage (e.g. malonamide, oxalamide, pyrazolones) and constraining of the acyclic acylthiourea structure fragment with various aromatic heterocycles. Further refinement included the blocking of the p-position of the pendant phenyl ring with a fluorine atom.[12] Example of interactions between c-Met and a small molecules (marked in a red circle) of class II are as follows: The scaffold of c-Met lodges into the ATP pocket by three key hydrogen bonds, the terminal amine interacts with the ribose pocket (of ATP), the terminal 4-fluorophenyl group is oriented in a hydrophobic pocket and pyrrolotriazine plays the role of the hinge-binding group.[12]

Examples of Class II inhibitors

In phase II clinical trials, GSK 1363089 (XL880, foretinib) was well tolerated. It led to slight regressions or stable disease in patients with papillary renal carcinoma and poorly differentiated gastric cancer.[12]

AMG 458 is a potent small molecule c-MET inhibitor which proved to have more than a 100-fold selectivity for c-MET across a panel of 55 kinases. Also, AMG 458 was 100% bioavailable across species and the intrinsic half-life increased with higher mammals.[12]

ATP non-competitive small molecule c-Met inhibitors

Tivantinib

This article appears to contradict the article Tivantinib. (November 2015) |

Clinical trials and regulatory approvals

Status as of 2010

Since the discovery of Met and HGF, much research interest has focused on their roles in cancer. The Met pathway is one of the most frequently dysregulated pathways in human cancer.[17] Increased understanding of the binding modes and structural design brings us closer to the use of other protein interactions and binding pockets, creating inhibitors with alternative structures and optimized profiles.[10]

As of 2010[update] over a dozen Met pathway inhibitors, with varying kinase selectivity profiles ranging from highly selective to multi-targeted,

The use of c-Met inhibitors with other therapeutic agents could be crucial for overcoming potential resistance as well as for improving overall clinical benefit. Met pathway inhibitors might be used in combination with other treatments, including

Since 2010

In 2011 PF-02341066 (now named crizotinib) was approved by

In 2012 XL184/cabozantinib gained FDA approval to treat medullary thyroid cancer, and in 2016 it gained FDA and EU approval to treat kidney cancer.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2018) |

Research on other inhibitors

Tepotinib, (MSC 2156119J),[26]

has reported phase II clinical trial results on lung cancer.[27] Tepotinib was granted breakthrough therapy designation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in September 2019.[28] It was granted orphan drug designation in Japan in November 2019, and in Australia in September 2020.[29]

See also

- Mesenchymal-epithelial transition

- Hepatocyte growth factor

- K252a

- Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- c-Met

External links

References

- S2CID 24415851.

- PMID 25170012.

- ^ "FDA approves Cometriq to treat rare type of thyroid cancer". Food and Drug Administration. 29 November 2012.

- ^ S2CID 24601127.

- PMID 11750879.

- PMID 20068147.

- PMID 19369077.

- ^ PMID 14559966

- ^ PMID 14500382

- ^ S2CID 22743228

- ^ PMID 14612533

- ^ PMID 20015007

- ^ PMID 20368753

- PMID 15922853

- PMID 18406132

- ^ Donald P. Bottaro; Megan Peach; Marec Nicklaus; Terrence Burke, JR.; Gagani Athauda; Sarah Choyke; Alessio Guibellino; Nelly Tan; Zhen-Dan Shi (August 2011), "Compositions and methods for inhibition of hepatocyte growth factor receptor c-Met signaling", United States Patent Application Publication

- ^ PMID 20031486

- PMID 17964000

- PMID 18055465

- ^ PMID 19199866

- ^ PMID 21454604

- PMID 21835616

- PMID 25745036.

- ^ Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, L.L.C. (2013-03-07). "A Phase I Study to Determine the Safety, Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of the Selective Met Inhibitor JNJ-38877605 in Subjects With Advanced or Refractory Solid Tumors". Ortho Biotech, Inc.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ S2CID 5293187

- ^ Tepotinib With Gefitinib in Subjects With Locally Advanced or Metastatic Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) (INSIGHT)

- ^ Phase II trial of the c-Met inhibitor tepotinib in advanced lung adenocarcinoma with MET exon 14 skipping mutations. 2017

- ^ "Tepotinib Breakthrough Therapy". Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany (Press release). 11 September 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ "Orphan Drug Designation". Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany (Press release). 20 November 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2020.