Cadmium

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cadmium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈkædmiəm/ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery bluish-gray metallic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Cd) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cadmium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 99.87 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 26.020 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Discovery and first isolation | Karl Samuel Leberecht Hermann and Friedrich Stromeyer (1817) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Named by | Friedrich Stromeyer (1817) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of cadmium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cadmium is a

Cadmium occurs as a minor component in most zinc ores and is a byproduct of zinc production. Cadmium was used for a long time[

Although cadmium has no known biological function in higher organisms, a cadmium-dependent carbonic anhydrase has been found in marine diatoms.

Characteristics

Physical properties

Cadmium is a soft,

Chemical properties

Although cadmium usually has an oxidation state of +2, it also exists in the +1 state. Cadmium and its congeners are not always considered transition metals, in that they do not have partly filled d or f electron shells in the elemental or common oxidation states.[11] Cadmium burns in air to form brown amorphous cadmium oxide (CdO); the crystalline form of this compound is a dark red which changes color when heated, similar to zinc oxide. Hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, and nitric acid dissolve cadmium by forming cadmium chloride (CdCl2), cadmium sulfate (CdSO4), or cadmium nitrate (Cd(NO3)2). The oxidation state +1 can be produced by dissolving cadmium in a mixture of cadmium chloride and aluminium chloride, forming the Cd22+ cation, which is similar to the Hg22+ cation in mercury(I) chloride.[8]

- Cd + CdCl2 + 2 AlCl3 → Cd2(AlCl4)2

The structures of many cadmium complexes with nucleobases, amino acids, and vitamins have been determined.[12]

Isotopes

Naturally occurring cadmium is composed of eight

The known isotopes of cadmium range in

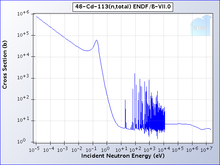

One isotope of cadmium, 113Cd,

Cadmium is created via the s-process in low- to medium-mass stars with masses of 0.6 to 10 solar masses, over thousands of years. In that process, a silver atom captures a neutron and then undergoes beta decay.[15]

History

Cadmium (

Even though cadmium and its compounds are toxic in certain forms and concentrations, the British Pharmaceutical Codex from 1907 states that cadmium iodide was used as a medication to treat "enlarged joints, scrofulous glands, and chilblains".[21]

In 1907, the

After the industrial scale production of cadmium started in the 1930s and 1940s, the major application of cadmium was the coating of iron and steel to prevent corrosion; in 1944, 62% and in 1956, 59% of the cadmium in the United States was used for plating.[7][25] In 1956, 24% of the cadmium in the United States was used for a second application in red, orange and yellow pigments from sulfides and selenides of cadmium.[25]

The stabilizing effect of cadmium chemicals like the carboxylates cadmium laurate and cadmium stearate on PVC led to an increased use of those compounds in the 1970s and 1980s. The demand for cadmium in pigments, coatings, stabilizers, and alloys declined as a result of environmental and health regulations in the 1980s and 1990s; in 2006, only 7% of total cadmium consumption was used for plating, and only 10% was used for pigments.[7] At the same time, these decreases in consumption were compensated by a growing demand for cadmium for nickel–cadmium batteries, which accounted for 81% of the cadmium consumption in the United States in 2006.[26]

Occurrence

Cadmium makes up about 0.1

Metallic cadmium can be found in the

Rocks mined for phosphate fertilizers contain varying amounts of cadmium, resulting in a cadmium concentration of as much as 300 mg/kg in the fertilizers and a high cadmium content in agricultural soils.

Cadmium in soil can be absorbed by crops such as rice and cocoa. In 2002, the

Some plants such as willow trees and poplars have been found to clean both lead and cadmium from soil.[35]

Typical background concentrations of cadmium do not exceed 5 ng/m3 in the atmosphere; 2 mg/kg in soil; 1 μg/L in freshwater and 50 ng/L in seawater.[36] Concentrations of cadmium above 10 μg/L may be stable in water having low total solute concentrations and p H and can be difficult to remove by conventional water treatment processes.[37]

Production

Cadmium is a common impurity in

The British Geological Survey reports that in 2001, China was the top producer of cadmium with almost one-sixth of the world's production, closely followed by South Korea and Japan.[40]

-

History of the world production of cadmium

-

Cadmium production in 2010.

Applications

Cadmium is a common component of electric batteries, pigments,[41] coatings,[42] and electroplating.[43]

Batteries

In 2009, 86% of cadmium was used in

Electroplating

Cadmium electroplating, consuming 6% of the global production, is used in the aircraft industry to reduce corrosion of steel components.[43] This coating is passivated by chromate salts.[42] A limitation of cadmium plating is hydrogen embrittlement of high-strength steels from the electroplating process. Therefore, steel parts heat-treated to tensile strength above 1300 MPa (200 ksi) should be coated by an alternative method (such as special low-embrittlement cadmium electroplating processes or physical vapor deposition).

Titanium embrittlement from cadmium-plated tool residues resulted in banishment of those tools (and the implementation of routine tool testing to detect cadmium contamination) in the A-12/SR-71, U-2, and subsequent aircraft programs that use titanium.[47]

Nuclear fission

Cadmium is used in the control rods of nuclear reactors, acting as a very effective neutron poison to control neutron flux in nuclear fission.[43] When cadmium rods are inserted in the core of a nuclear reactor, cadmium absorbs neutrons, preventing them from creating additional fission events, thus controlling the amount of reactivity. The pressurized water reactor designed by Westinghouse Electric Company uses an alloy consisting of 80% silver, 15% indium, and 5% cadmium.[43]

Televisions

QLED TVs have been starting to include cadmium in construction. Some companies have been looking to reduce the environmental impact of human exposure and pollution of the material in televisions during production.[48]

Anticancer drugs

Complexes based on cadmium and other heavy metals have potential for the treatment of cancer, but their use is often limited due to toxic side effects.[49]

Compounds

Cadmium oxide was used in black and white television phosphors and in the blue and green phosphors of color television cathode ray tubes.[50] Cadmium sulfide (CdS) is used as a photoconductive surface coating for photocopier drums.[51]

Various cadmium salts are used in paint pigments, with CdS as a

In

Semiconductors

Cadmium is an element in some

and used in some motion detectors.Laboratory uses

Helium–cadmium lasers are a common source of blue or ultraviolet laser light. Lasers at wavelengths of 325, 354 and 442 nm are made using this

Cadmium selenide quantum dots emit bright luminescence under UV excitation (He–Cd laser, for example). The color of this luminescence can be green, yellow or red depending on the particle size. Colloidal solutions of those particles are used for imaging of biological tissues and solutions with a fluorescence microscope.[56]

In molecular biology, cadmium is used to block

Cadmium-selective sensors based on the fluorophore BODIPY have been developed for imaging and sensing of cadmium in cells.[58] One powerful method for monitoring cadmium in aqueous environments involves electrochemistry. By employing a self-assembled monolayer one can obtain a cadmium selective electrode with a ppt-level sensitivity.[59]

Biological role

Cadmium has no known function in higher organisms and is considered toxic.[60] Cadmium is considered an environmental pollutant hazardous to living organisms.[61] A cadmium-dependent carbonic anhydrase has been found in some marine diatoms,[62] which live in environments with low zinc concentrations.[63]

Cadmium is preferentially absorbed in the kidneys of humans. Up to about 30 mg of cadmium is commonly inhaled throughout human childhood and adolescence.[64]

Cadmium is under research for its potential toxicity to increase the risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and osteoporosis.[65][66][67][68]

Environmental impact

The biogeochemistry of cadmium and its release to the environment is under research.[69][70]

Safety

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling:[71] | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H301, H330, H341, H350, H361fd, H372, H410 | |

| P201, P202, P260, P264, P273, P304+P340+P310 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Individuals and organizations have been reviewing cadmium's bioinorganic aspects for its toxicity.[72] The most dangerous form of occupational exposure to cadmium is inhalation of fine dust and fumes, or ingestion of highly soluble cadmium compounds.[7] Inhalation of cadmium fumes can result initially in metal fume fever, but may progress to chemical pneumonitis, pulmonary edema, and death.[73]

Cadmium is also an environmental hazard. Human exposure is primarily from fossil fuel combustion, phosphate fertilizers, natural sources, iron and steel production, cement production and related activities, nonferrous metals production, and municipal solid waste incineration.[7] Other sources of cadmium include bread, root crops, and vegetables.[74]

There have been a few instances of general population poisoning as the result of long-term exposure to cadmium in contaminated food and water. Research into an estrogen mimicry that may induce breast cancer is ongoing, as of 2012[update].

Cadmium is one of six substances banned by the European Union's

The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified cadmium and cadmium compounds as carcinogenic to humans.[77] Although occupational exposure to cadmium is linked to lung and prostate cancer, there is still uncertainty about the carcinogenicity of cadmium in low environmental exposure. Recent data from epidemiological studies suggest that intake of cadmium through diet is associated with a higher risk of endometrial, breast, and prostate cancer as well as with osteoporosis in humans.[78][79][80][81] A recent study has demonstrated that endometrial tissue is characterized by higher levels of cadmium in current and former smoking females.[82]

Cadmium exposure is associated with a large number of illnesses including kidney disease,

The

In a non-smoking population, food is the greatest source of exposure. High quantities of cadmium can be found in

Zinc, copper, calcium, and iron ions, and selenium with vitamin C are used to treat cadmium intoxication, though it is not easily reversed.[83]

Regulations

Because of the adverse effects of cadmium on the environment and human health, the supply and use of cadmium is restricted in Europe under the

The EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain specifies that 2.5 μg/kg body weight is a tolerable weekly intake for humans.[93] The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives has declared 7 μg/kg body weight to be the provisional tolerable weekly intake level.[96] The state of California requires a food label to carry a warning about potential exposure to cadmium on products such as cocoa powder.[97] The European Commission has put in place the EU regulation (2019/1009) on fertilizing products (EU, 2019), adopted in June 2019 and fully applicable as of July 2022, sets a Cd limit value in phosphate fertilizers to 60 mg kg-1 of P2O5.

The U.S.

| Lethal dose[99] | Organism | Route | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| LD50: 225 mg/kg | rat | oral | n/a |

| LD50: 890 mg/kg | mouse | oral | n/a |

| LC50: 25 mg/m3 | rat | airborne | 30 min |

In addition to mercury, the presence of cadmium in some batteries has led to the requirement of proper disposal (or recycling) of batteries.

Product recalls

In May 2006, a sale of the seats from

In June 2010,

See also

Notes

- ^ The thermal expansion is anisotropic: the parameters (at 20 °C) for each crystal axis are αa = 18.91×10−6/K, αc = 55.03×10−6/K, and αaverage = αV/3 = 30.95×10−6/K.[3]

References

- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Cadmium". CIAAW. 2013.

- ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-62708-155-9.

- ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-471-23896-6.

- ^ a b

Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E.; Wiberg, Nils (1985). "Cadmium". Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie, 91–100 (in German). ISBN 978-3-11-007511-3.

- ^ "Cadmium 3.2.6 Solubility". PubChem. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Case Studies in Environmental Medicine (CSEM) Cadmium". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ^

Cotton, F. A. (1999). "Survey of Transition-Metal Chemistry". Advanced Inorganic Chemistry (6th ed.). ISBN 978-0-471-19957-1.

- PMID 23430774.

- ^

- ^

Knoll, G. F. (2000). Radiation Detection and Measurement. ISBN 978-0-471-07338-3.

- ^

Padmanabhan, T. (2001). "Stellar Nucleosynthesis". Theoretical Astrophysics, Volume II: Stars and Stellar Systems. ISBN 978-0-521-56631-5.

- ^ Rolof (1795). "Wichtige Nachricht für Aerzte und Apoteker – Entdeckung eines Arsenikgehalts in der Zinkblume und des Zinkvitriols in Tartarus vitriolis". Journal des practischen Arzneykunde und Wundarzneykunst (Hufelands Journal) (2 Februar Stück): 110.

- ^ Hermann, C. S. (1818). "Noch ein schreiben über das neue Metall". .

- ^

Waterston, W.; Burton, J. H. (1844). Cyclopædia of commerce, mercantile law, finance, commercial geography and navigation. H. G. Bohn. p. 122.

- ^ Rowbotham, T.; Rowbotham, T. L. (1850). The Art of Landscape Painting in Water Colours. Windsor and Newton. p. 10.

- ^ a b

Ayres, R. U.; Ayres, L.; Råde, I. (2003). The Life Cycle of Copper, Its Co-Products and Byproducts. ISBN 978-1-4020-1552-6.

- ^

Dunglison, R. (1866). Medical Lexicon: A Dictionary of Medical Science. Henry C. Lea. pp. 159.

- ^ "International Angstrom". Science Dictionary. 14 September 2013. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ "angstrom or ångström". Sizes.com. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^

Burdun, G. D. (1958). "On the new determination of the meter". Measurement Techniques. 1 (3): 259–264. S2CID 121450003.

- ^ a b Lansche, A. M. (1956). "Cadmium". Minerals Yearbook, Volume I: Metals and Minerals (Except Fuels). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- ^ "USGS Mineral Information: Cadmium". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ Wedepohl, K. H. (1995). "The composition of the continental crust". .

- ^

Plachy, J. (1998). "Annual Average Cadmium Price" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 17–19. Archived(PDF) from the original on 16 August 2000. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ a b Fthenakis, V. M. (2004). "Life cycle impact analysis of cadmium in CdTe PV production". .

- ^ Fleischer, M.; Cabri, L. J.; Chao, G. Y.; Pabst, A. (1980). "New Mineral Names" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 65: 1065–1070. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022.

- S2CID 84548398.

- .

- .

- ^ Dark chocolate is high in cadmium and lead. How much is safe to eat?

- ^ "The most neglected threat to public health in China is toxic soil". The Economist. 8 June 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^

Rieuwerts, J. (2015). The Elements of Environmental Pollution. Routledge. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-415-85920-2.

- ISSN 1944-7973.

- ^ a b Golberg, D. C.; et al. (1969). Trends in Usage of Cadmium: Report. . pp. 1–3.

- ^

Scoullos, M. J. (2001). Mercury, Cadmium, Lead: Handbook for Sustainable Heavy Metals Policy and Regulation. ISBN 978-1-4020-0224-3.

- ^ Hetherington, L. E.; et al. (2008). "Production of Cadmium" (PDF). World Mineral Production 2002–06. British Geological Survey. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ ]

- ^ a b Smith, C.J.E.; Higgs, M.S.; Baldwin, K.R. (20 April 1999). "Advances to Protective Coatings and their Application to Ageing Aircraft". RTO MP-25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4020-0224-3.

- ISBN 978-81-203-3666-7.

- ^ "EUR-Lex - 32011L0065 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ "Directive 2006/66/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council". EUR-lex.europa.eu. 26 September 2006. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ "CIA – Breaking Through Technological Barriers – Finding The Right Metal (A-12 program)". 1 October 2007. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007.

- ^ Maynard, Andrew. "Are quantum dot TVs – and their toxic ingredients – actually better for the environment?". The Conversation. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- PMID 31604983.

- PMID 11811492.

- ISBN 978-0-306-43655-0.

- ISBN 978-1-56990-379-7.

- ISBN 978-0-07-136076-0.

- ^ "Helium–Cadmium Lasers". Olympus. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ISBN 978-81-224-1492-9.

- ^ "Cadmium Selenium Testing for Microbial Contaminants". NASA. 10 June 2003. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- PMID 10866824.

- PMID 23430772.

- PMID 21167979.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (2010). Heavy metal. Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. E. Monosson and C. Cleveland (eds.). Washington DC.

- PMID 32323337.

- S2CID 52819760.

- PMID 10781068.

- PMID 775217.

- PMID 25272057.

- (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022.

- PMID 23955722.

- S2CID 11265947.

- ^

Cullen, Jay T.; Maldonado, Maria T. (2013). "Biogeochemistry of Cadmium and Its Release to the Environment". In Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Roland K. O. Sigel (eds.). Cadmium: From Toxicity to Essentiality. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 11. Springer. pp. 31–62. PMID 23430769.

- PMID 23430770.

- ^ GHS: "Safety Data Sheet". Sigma-Aldrich. 12 September 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- PMID 23430768.

- ISBN 978-0-8493-3778-9.

- ^ a b Mann, Denise (23 April 2012) Can Heavy Metal in Foods, Cosmetics Spur Breast Cancer Spread? HealthDayBy via Yahoo

- S2CID 8053594.

- ^ "European Commission Decision of 12 October 2006 amending, for the purposes of adapting to technical progress, the Annex to Directive 2002/95/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards exemptions for applications of lead and cadmium (notified under document number C(2006) 4790)". Journal of the European Union. 14 October 2006.

- OCLC 29943893.

- PMID 22850555.

- PMID 22465267.

- PMID 22422990.

- PMID 18676869.

- PMID 24834829.

- ^ a b "ARL : Cadmium Toxicity". www.arltma.com. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ Cadmium Exposure can Induce Early Atherosclerotic Changes Archived 15 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Medinews Direct, 7 September 2009

- PMID 21829690.

- PMID 10770491.

- PMID 20525538.

- PMID 22314386.

- S2CID 39484160.

- PMID 22284492.

- PMID 6860444.

- PMID 9569444.

- ^ a b "Cadmium dietary exposure in the European population – European Food Safety Authority". www.efsa.europa.eu. 18 January 2012.

- PMID 38008327.

- ^ EUR-Lex. Eur-lex.europa.eu (18 April 2011). Retrieved on 5 June 2011.

- ^ "JECFA Evaluations-CADMIUM-". www.inchem.org.

- ^ such as seen on the organic cocoa powder marketed by Better Body Foods, for example

- ^ NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0087". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ "Cadmium compounds (as Cd)". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ "Toxic fears hit Highbury auction". BBC Sport. 10 May 2006. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ^ "U.S. to Develop Safety Standards for Toxic Metals". Business Week. 12 January 2010. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ "Claire's Recalls Children's Metal Charm Bracelets Due to High Levels of Cadmium". U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. 10 May 2010. Archived from the original on 31 May 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- ^ "FAF Inc. Recalls Children's Necklaces Sold Exclusively at Walmart Stores Due to High Levels of Cadmium". U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. 29 January 2010. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- ^ Neuman, William (4 June 2010). "McDonald's Recalls 12 Million 'Shrek' Glasses". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- ^ "McDonald's Recalls Movie Themed Drinking Glasses Due to Potential Cadmium Risk". U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. 4 June 2010. Archived from the original on 7 June 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

Further reading

- Hartwig, Andrea (2013). "Cadmium and Cancer". In Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Roland K. O. Sigel (eds.). Cadmium: From Toxicity to Essentiality. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 11. Springer. pp. 491–507. PMID 23430782.

External links

- Cadmium at The Periodic Table of Videos(University of Nottingham)

- ATSDR Case Studies in Environmental Medicine: Cadmium Toxicity U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health – Cadmium Page

- NLM Hazardous Substances Databank – Cadmium, Elemental