Caffeine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /kæˈfiːn, ˈkæfiːn/ |

| Other names | Guaranine Methyltheobromine 1,3,7-Trimethylxanthine 7-methyltheophylline[1] Theine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Physical: Moderate 13% and variable low–high 10-73%[2] |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 99%[4] |

| Protein binding | 10–36%[5] |

| Metabolism | Primary: CYP1A2[5] Minor: CYP2E1,[5] CYP3A4,[5] CYP2C8,[5] CYP2C9[5] |

| Metabolites | • Paraxanthine 84% • Theobromine 12% • Theophylline 4% |

| Onset of action | 45 minutes–1 hour[4][6] |

| Elimination half-life | Adults: 3–7 hours[5] Infants (full term): 8 hours[5] Infants (premature): 100 hours[5] |

| Duration of action | 3–4 hours[4] |

| Excretion | Urine (100%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.23 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 235 to 238 °C (455 to 460 °F) (anhydrous)[7][8] |

| |

| |

| Data page | |

| Caffeine (data page) | |

Caffeine is a

Caffeine is a bitter, white crystalline

Caffeine has both positive and negative health effects. It can treat and prevent the premature infant breathing disorders

Caffeine is classified by the US

Uses

Medical

Caffeine is used for both prevention

Caffeine is used as a primary treatment for apnea of prematurity,[39] but not prevention.[40][41] It is also used for orthostatic hypotension treatment.[42][41][43]

Some people use caffeine-containing beverages such as coffee or tea to try to treat their

The addition of caffeine (100–130 mg) to commonly prescribed pain relievers such as

Consumption of caffeine after abdominal surgery shortens the time to recovery of normal bowel function and shortens length of hospital stay.[47]

Caffeine was formerly used as a second-line treatment for

Enhancing performance

Cognitive performance

Caffeine is a

Caffeine can delay or prevent sleep and improves task performance during sleep deprivation.[53] Shift workers who use caffeine make fewer mistakes that could result from drowsiness.[54]

Caffeine in a dose dependent manner increases alertness in both fatigued and normal individuals.[55]

A

Physical performance

Caffeine is a proven

Caffeine improves muscular strength and power,[65] and may enhance muscular endurance.[66] Caffeine also enhances performance on anaerobic tests.[67] Caffeine consumption before constant load exercise is associated with reduced perceived exertion. While this effect is not present during exercise-to-exhaustion exercise, performance is significantly enhanced. This is congruent with caffeine reducing perceived exertion, because exercise-to-exhaustion should end at the same point of fatigue.[68] Caffeine also improves power output and reduces time to completion in aerobic time trials,[69] an effect positively (but not exclusively) associated with longer duration exercise.[70]

Specific populations

Adults

For the general population of healthy adults, Health Canada advises a daily intake of no more than 400 mg.[71] This limit was found to be safe by a 2017 systematic review on caffeine toxicology.[72]

Children

In healthy children, moderate caffeine intake under 400 mg produces effects that are "modest and typically innocuous".

| Age range | Maximum recommended daily caffeine intake |

|---|---|

| 4–6 | 45 mg (slightly more than in 355 ml (12 fl. oz) of a typical caffeinated soft drink) |

| 7–9 | 62.5 mg |

| 10–12 | 85 mg (about 1⁄2 cup of coffee) |

Adolescents

Health Canada has not developed advice for adolescents because of insufficient data. However, they suggest that daily caffeine intake for this age group be no more than 2.5 mg/kg body weight. This is because the maximum adult caffeine dose may not be appropriate for light-weight adolescents or for younger adolescents who are still growing. The daily dose of 2.5 mg/kg body weight would not cause adverse health effects in the majority of adolescent caffeine consumers. This is a conservative suggestion since older and heavier-weight adolescents may be able to consume adult doses of caffeine without experiencing adverse effects.[71]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

The metabolism of caffeine is reduced in pregnancy, especially in the third trimester, and the half-life of caffeine during pregnancy can be increased up to 15 hours (as compared to 2.5 to 4.5 hours in non-pregnant adults).[78] Evidence regarding the effects of caffeine on pregnancy and for breastfeeding are inconclusive.[25] There is limited primary and secondary advice for, or against, caffeine use during pregnancy and its effects on the fetus or newborn.[25]

The UK

There are conflicting reports in the scientific literature about caffeine use during pregnancy.

Adverse effects

Physiological

Caffeine in coffee and other

Acute ingestion of caffeine in large doses (at least 250–300 mg, equivalent to the amount found in 2–3 cups of coffee or 5–8 cups of tea) results in a short-term stimulation of urine output in individuals who have been deprived of caffeine for a period of days or weeks.[90] This increase is due to both a diuresis (increase in water excretion) and a natriuresis (increase in saline excretion); it is mediated via proximal tubular adenosine receptor blockade.[91] The acute increase in urinary output may increase the risk of dehydration. However, chronic users of caffeine develop a tolerance to this effect and experience no increase in urinary output.[92][93][94]

Psychological

Minor undesired symptoms from caffeine ingestion not sufficiently severe to warrant a psychiatric diagnosis are common and include mild anxiety, jitteriness, insomnia, increased sleep latency, and reduced coordination.

In moderate doses, caffeine has been associated with reduced symptoms of

Some textbooks state that caffeine is a mild euphoriant,[103][104][105] while others state that it is not a euphoriant.[106][107]

Caffeine-induced anxiety disorder is a subclass of the DSM-5 diagnosis of substance/medication-induced anxiety disorder.[108]

Reinforcement disorders

Addiction

Whether caffeine can result in an addictive disorder depends on how addiction is defined. Compulsive caffeine consumption under any circumstances has not been observed, and caffeine is therefore not generally considered addictive.

Caffeine does not appear to be a reinforcing stimulus, and some degree of aversion may actually occur, with people preferring placebo over caffeine in a study on drug abuse liability published in an NIDA research monograph.[112] Some state that research does not provide support for an underlying biochemical mechanism for caffeine addiction.[27][113][114][115] Other research states it can affect the reward system.[116]

"Caffeine addiction" was added to the ICDM-9 and ICD-10. However, its addition was contested with claims that this diagnostic model of caffeine addiction is not supported by evidence.[27][117][118] The American Psychiatric Association's DSM-5 does not include the diagnosis of a caffeine addiction but proposes criteria for the disorder for more study.[108][119]

Dependence and withdrawal

Withdrawal can cause mild to clinically significant distress or impairment in daily functioning. The frequency at which this occurs is self-reported at 11%, but in lab tests only half of the people who report withdrawal actually experience it, casting doubt on many claims of dependence.[120] and most cases of caffeine withdrawal were 13% in the moderate sense. moderately physical dependence and withdrawal symptoms may occur upon abstinence, with greater than 100 mg caffeine per day, although these symptoms last no longer than a day.[27] Some symptoms associated with psychological dependence may also occur during withdrawal.[2] The diagnostic criteria for caffeine withdrawal require a previous prolonged daily use of caffeine.[121] Following 24 hours of a marked reduction in consumption, a minimum of 3 of these signs or symptoms is required to meet withdrawal criteria: difficulty concentrating, depressed mood/irritability, flu-like symptoms, headache, and fatigue.[121] Additionally, the signs and symptoms must disrupt important areas of functioning and are not associated with effects of another condition.[121]

The ICD-11 includes caffeine dependence as a distinct diagnostic category, which closely mirrors the DSM-5's proposed set of criteria for "caffeine-use disorder".[119][122] Caffeine use disorder refers to dependence on caffeine characterized by failure to control caffeine consumption despite negative physiological consequences.[119][122] The APA, which published the DSM-5, acknowledged that there was sufficient evidence in order to create a diagnostic model of caffeine dependence for the DSM-5, but they noted that the clinical significance of the disorder is unclear.[123] Due to this inconclusive evidence on clinical significance, the DSM-5 classifies caffeine-use disorder as a "condition for further study".[119]

Tolerance to the effects of caffeine occurs for caffeine-induced elevations in blood pressure and the subjective feelings of nervousness. Sensitization, the process whereby effects become more prominent with use, occurs for positive effects such as feelings of alertness and wellbeing.[120] Tolerance varies for daily, regular caffeine users and high caffeine users. High doses of caffeine (750 to 1200 mg/day spread throughout the day) have been shown to produce complete tolerance to some, but not all of the effects of caffeine. Doses as low as 100 mg/day, such as a 6 oz (170 g) cup of coffee or two to three 12 oz (340 g) servings of caffeinated soft-drink, may continue to cause sleep disruption, among other intolerances. Non-regular caffeine users have the least caffeine tolerance for sleep disruption.[124] Some coffee drinkers develop tolerance to its undesired sleep-disrupting effects, but others apparently do not.[125]

Risk of other diseases

A neuroprotective effect of caffeine against Alzheimer's disease and dementia is possible but the evidence is inconclusive.[126][127]

Regular consumption of caffeine may protect people from

Caffeine may lessen the severity of

Caffeine increases intraocular pressure in those with glaucoma but does not appear to affect normal individuals.[134]

The DSM-5 also includes other caffeine-induced disorders consisting of caffeine-induced anxiety disorder, caffeine-induced sleep disorder and unspecified caffeine-related disorders. The first two disorders are classified under "Anxiety Disorder" and "Sleep-Wake Disorder" because they share similar characteristics. Other disorders that present with significant distress and impairment of daily functioning that warrant clinical attention but do not meet the criteria to be diagnosed under any specific disorders are listed under "Unspecified Caffeine-Related Disorders".[135]

Energy crash

Caffeine is reputed to cause a fall in energy several hours after drinking, but this is not well researched.[136][137][138][139]

Overdose

PMID 30893206. You can help by adding to it . (November 2019) |

Consumption of 1–1.5 grams (1,000–1,500 mg) per day is associated with a condition known as caffeinism.[141] Caffeinism usually combines caffeine dependency with a wide range of unpleasant symptoms including nervousness, irritability, restlessness, insomnia, headaches, and palpitations after caffeine use.[142]

Caffeine overdose can result in a state of central nervous system overstimulation known as caffeine intoxication, a clinically significant temporary condition that develops during, or shortly after, the consumption of caffeine.[143] This syndrome typically occurs only after ingestion of large amounts of caffeine, well over the amounts found in typical caffeinated beverages and caffeine tablets (e.g., more than 400–500 mg at a time). According to the DSM-5, caffeine intoxication may be diagnosed if five (or more) of the following symptoms develop after recent consumption of caffeine: restlessness, nervousness, excitement, insomnia, flushed face, diuresis, gastrointestinal disturbance, muscle twitching, rambling flow of thought and speech, tachycardia or cardiac arrhythmia, periods of inexhaustibility, and psychomotor agitation.[144]

According to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), cases of very high caffeine intake (e.g. > 5 g) may result in caffeine intoxication with symptoms including mania, depression, lapses in judgment, disorientation, disinhibition, delusions, hallucinations or psychosis, and rhabdomyolysis.[143]

Energy drinks

High caffeine consumption in energy drinks (at least one liter or 320 mg of caffeine) was associated with short-term cardiovascular side effects including hypertension, prolonged QT interval, and heart palpitations. These cardiovascular side effects were not seen with smaller amounts of caffeine consumption in energy drinks (less than 200 mg).[78]

Severe intoxication

As of 2007[update] there is no known antidote or reversal agent for caffeine intoxication. Treatment of mild caffeine intoxication is directed toward symptom relief; severe intoxication may require

Lethal dose

Death from caffeine ingestion appears to be rare, and most commonly caused by an intentional overdose of medications.

Interactions

Caffeine is a substrate for CYP1A2, and interacts with many substances through this and other mechanisms.[155]

Alcohol

According to DSST, alcohol causes a decrease in performance on their standardized tests, and caffeine causes a significant improvement.[156] When alcohol and caffeine are consumed jointly, the effects of the caffeine are changed, but the alcohol effects remain the same.[157] For example, consuming additional caffeine does not reduce the effect of alcohol.[157] However, the jitteriness and alertness given by caffeine is decreased when additional alcohol is consumed.[157] Alcohol consumption alone reduces both inhibitory and activational aspects of behavioral control. Caffeine antagonizes the activational aspect of behavioral control, but has no effect on the inhibitory behavioral control.[158] The Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend avoidance of concomitant consumption of alcohol and caffeine, as taking them together may lead to increased alcohol consumption, with a higher risk of alcohol-associated injury.

Tobacco

Smoking tobacco increases caffeine clearance by 56%.[159] Cigarette smoking induces the cytochrome P450 1A2 enzyme that breaks down caffeine, which may lead to increased caffeine tolerance and coffee consumption for regular smokers.[160]

Birth control

Medications

Caffeine sometimes increases the effectiveness of some medications, such as those for

The pharmacological effects of adenosine may be blunted in individuals taking large quantities of

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

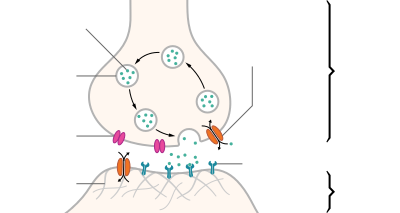

In the absence of caffeine and when a person is awake and alert, little

Receptor and ion channel targets

Caffeine is an

Antagonism of adenosine receptors by caffeine also stimulates the

Because caffeine is both water- and lipid-soluble, it readily crosses the

In addition to its activity at adenosine receptors, caffeine is an

Effects on striatal dopamine

While caffeine does not directly bind to any

Caffeine also causes the release of dopamine in the

Enzyme targets

Caffeine, like other

Pharmacokinetics

Caffeine from coffee or other beverages is absorbed by the small intestine within 45 minutes of ingestion and distributed throughout all bodily tissues.

Caffeine's

Caffeine is

- Paraxanthine (84%): Increases lipolysis, leading to elevated glycerol and free fatty acid levels in blood plasma.

- Theobromine (12%): Dilates blood vessels and increases urine volume. Theobromine is also the principal alkaloid in the cocoa bean (chocolate).

- therapeutic dose of theophylline, however, is many times greater than the levels attained from caffeine metabolism.[45]

1,3,7-Trimethyluric acid is a minor caffeine metabolite.[5] 7-Methylxanthine is also a metabolite of caffeine.[192][193] Each of the above metabolites is further metabolized and then excreted in the urine. Caffeine can accumulate in individuals with severe liver disease, increasing its half-life.[194]

A 2011 review found that increased caffeine intake was associated with a variation in two genes that increase the rate of caffeine catabolism. Subjects who had this

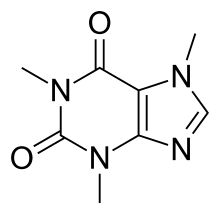

Chemistry

Pure

The

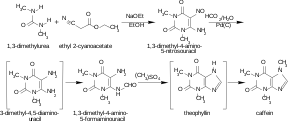

Synthesis

The biosynthesis of caffeine is an example of convergent evolution among different species.[205][206][207]

Caffeine may be synthesized in the lab starting with dimethylurea and malonic acid.[clarification needed][203][204][208]

Commercial supplies of caffeine are not usually manufactured synthetically because the chemical is readily available as a byproduct of decaffeination.[209]

Decaffeination

Extraction of caffeine from coffee, to produce caffeine and decaffeinated coffee, can be performed using a number of solvents. Following are main methods:

- Water extraction: Coffee beans are soaked in water. The water, which contains many other compounds in addition to caffeine and contributes to the flavor of coffee, is then passed through activated charcoal, which removes the caffeine. The water can then be put back with the beans and evaporated dry, leaving decaffeinated coffee with its original flavor. Coffee manufacturers recover the caffeine and resell it for use in soft drinks and over-the-counter caffeine tablets.[210]

- Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction: atm. Under these conditions, CO2 is in a "supercritical" state: It has gaslike properties that allow it to penetrate deep into the beans but also liquid-like properties that dissolve 97–99% of the caffeine. The caffeine-laden CO2 is then sprayed with high-pressure water to remove the caffeine. The caffeine can then be isolated by charcoal adsorption (as above) or by distillation, recrystallization, or reverse osmosis.[210]

- Extraction by organic solvents: Certain organic solvents such as ethyl acetate present much less health and environmental hazard than chlorinated and aromatic organic solvents used formerly. Another method is to use triglyceride oils obtained from spent coffee grounds.[210]

"Decaffeinated" coffees do in fact contain caffeine in many cases – some commercially available decaffeinated coffee products contain considerable levels. One study found that decaffeinated coffee contained 10 mg of caffeine per cup, compared to approximately 85 mg of caffeine per cup for regular coffee.[211]

Detection in body fluids

Caffeine can be quantified in blood, plasma, or serum to monitor therapy in

Analogs

Some analog substances have been created which mimic caffeine's properties with either function or structure or both. Of the latter group are the

Some other caffeine analogs:

Precipitation of tannins

Caffeine, as do other alkaloids such as cinchonine, quinine or strychnine, precipitates polyphenols and tannins. This property can be used in a quantitation method.[clarification needed][216]

Natural occurrence

Around thirty plant species are known to contain caffeine.[217] Common sources are the "beans" (seeds) of the two cultivated coffee plants, Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora (the quantity varies, but 1.3% is a typical value); and of the cocoa plant, Theobroma cacao; the leaves of the tea plant; and kola nuts. Other sources include the leaves of yaupon holly, South American holly yerba mate, and Amazonian holly guayusa; and seeds from Amazonian maple guarana berries. Temperate climates around the world have produced unrelated caffeine-containing plants.

Caffeine in plants acts as a natural pesticide: it can paralyze and kill predator insects feeding on the plant.[218] High caffeine levels are found in coffee seedlings when they are developing foliage and lack mechanical protection.[219] In addition, high caffeine levels are found in the surrounding soil of coffee seedlings, which inhibits seed germination of nearby coffee seedlings, thus giving seedlings with the highest caffeine levels fewer competitors for existing resources for survival.[220] Caffeine is stored in tea leaves in two places. Firstly, in the cell vacuoles where it is complexed with polyphenols. This caffeine probably is released into the mouth parts of insects, to discourage herbivory. Secondly, around the vascular bundles, where it probably inhibits pathogenic fungi from entering and colonizing the vascular bundles.[221] Caffeine in nectar may improve the reproductive success of the pollen producing plants by enhancing the reward memory of pollinators such as honey bees.[17]

The differing perceptions in the effects of ingesting beverages made from various plants containing caffeine could be explained by the fact that these beverages also contain varying mixtures of other

Products

| Product | Serving size | Caffeine per serving ( mg )

|

Caffeine (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeine tablet (regular-strength) | 1 tablet | 100 | — |

| Caffeine tablet (extra-strength) | 1 tablet | 200 | — |

Excedrin tablet

|

1 tablet | 65 | — |

| Hershey's Special Dark (45% cacao content) | 1 bar (43 g or 1.5 oz) | 31 | — |

Hershey's Milk Chocolate (11% cacao content)

|

1 bar (43 g or 1.5 oz) | 10 | — |

| Percolated coffee | 207 US fl oz )

|

80–135 | 386–652 |

Drip coffee

|

207 mL (7.0 US fl oz) | 115–175 | 555–845 |

| Coffee, decaffeinated

|

207 mL (7.0 US fl oz) | 5–15 | 24–72 |

| Coffee, espresso | 44–60 mL (1.5–2.0 US fl oz) | 100 | 1,691–2,254 |

| Tea – black, green, and other types, – steeped for 3 min. | 177 mL (6.0 US fl oz) | 22–74[226][227] | 124–418 |

| Guayakí yerba mate (loose leaf)

|

6 g (0.21 oz) | 85[228] | approx. 358 |

| Coca-Cola | 355 mL (12.0 US fl oz) | 34 | 96 |

| Mountain Dew | 355 mL (12.0 US fl oz) | 54 | 154 |

| Pepsi Zero Sugar | 355 mL (12.0 US fl oz) | 69 | 194 |

| Guaraná Antarctica | 350 mL (12 US fl oz) | 30 | 100 |

| Jolt Cola | 695 mL (23.5 US fl oz) | 280 | 403 |

| Red Bull | 250 mL (8.5 US fl oz) | 80 | 320 |

| Coffee-flavored milk drink | 300–600 mL (10–20 US fl oz) | 33–197[229] | 66–354[229] |

Products containing caffeine include coffee, tea, soft drinks ("colas"), energy drinks, other beverages, chocolate,[230] caffeine tablets, other oral products, and inhalation products. According to a 2020 study in the United States, coffee is the major source of caffeine intake in middle-aged adults, while soft drinks and tea are the major sources in adolescents.[78] Energy drinks are more commonly consumed as a source of caffeine in adolescents as compared to adults.[78]

Beverages

Coffee

The world's primary source of caffeine is the coffee "bean" (the seed of the coffee plant), from which coffee is brewed. Caffeine content in coffee varies widely depending on the type of coffee bean and the method of preparation used;[231] even beans within a given bush can show variations in concentration. In general, one serving of coffee ranges from 80 to 100 milligrams, for a single shot (30 milliliters) of arabica-variety espresso, to approximately 100–125 milligrams for a cup (120 milliliters) of drip coffee.[232][233] Arabica coffee typically contains half the caffeine of the robusta variety.[231] In general, dark-roast coffee has very slightly less caffeine than lighter roasts because the roasting process reduces caffeine content of the bean by a small amount.[232][233]

Tea

Tea contains more caffeine than coffee by dry weight. A typical serving, however, contains much less, since less of the product is used as compared to an equivalent serving of coffee. Also contributing to caffeine content are growing conditions, processing techniques, and other variables. Thus, teas contain varying amounts of caffeine.[234]

Tea contains small amounts of theobromine and slightly higher levels of theophylline than coffee. Preparation and many other factors have a significant impact on tea, and color is a very poor indicator of caffeine content. Teas like the pale Japanese green tea, gyokuro, for example, contain far more caffeine than much darker teas like lapsang souchong, which has very little.[234]

Soft drinks and energy drinks

Caffeine is also a common ingredient of

Other beverages

- Mate is a drink popular in many parts of South America. Its preparation consists of filling a gourd with the leaves of the South American holly yerba mate, pouring hot but not boiling water over the leaves, and drinking with a straw, the bombilla, which acts as a filter so as to draw only the liquid and not the yerba leaves.[237]

- Guaranáfruit.

- The leaves of Ilex guayusa, the Ecuadorian holly tree, are placed in boiling water to make a guayusa tea.[238]

- The leaves of Ilex vomitoria, the yaupon holly tree, are placed in boiling water to make a yaupon tea.

- Commercially prepared coffee-flavoured milk beverages are popular in Australia.[239] Examples include Oak's Ice Coffee and Farmers Union Iced Coffee. The amount of caffeine in these beverages can vary widely. Caffeine concentrations can differ significantly from the manufacturer's claims.[229]

Chocolate

Chocolate derived from cocoa beans contains a small amount of caffeine. The weak stimulant effect of chocolate may be due to a combination of theobromine and theophylline, as well as caffeine.[240] A typical 28-gram serving of a milk chocolate bar has about as much caffeine as a cup of decaffeinated coffee. By weight, dark chocolate has one to two times the amount of caffeine as coffee: 80–160 mg per 100 g. Higher percentages of cocoa such as 90% amount to 200 mg per 100 g approximately and thus, a 100-gram 85% cocoa chocolate bar contains about 195 mg caffeine.[224]

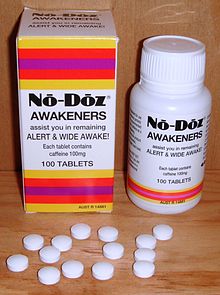

Tablets

Tablets offer several advantages over coffee, tea, and other caffeinated beverages, including convenience, known dosage, and avoidance of concomitant intake of sugar, acids, and fluids. A use of caffeine in this form is said to improve mental alertness.[241] These tablets are commonly used by students studying for their exams and by people who work or drive for long hours.[242]

Other oral products

One U.S. company is marketing oral dissolvable caffeine strips.[243] Another intake route is SpazzStick, a caffeinated lip balm.[244] Alert Energy Caffeine Gum was introduced in the United States in 2013, but was voluntarily withdrawn after an announcement of an investigation by the FDA of the health effects of added caffeine in foods.[245]

Inhalants

Similar to an

Combinations with other drugs

- Some beverages combine United States Food and Drug Administration has classified caffeine added to malt liquor beverages as an "unsafe food additive".[249]

- Ya ba contains a combination of methamphetamine and caffeine.

- Painkillers such as propyphenazone/paracetamol/caffeine combine caffeine with an analgesic.

History

Discovery and spread of use

According to Chinese legend, the

The earliest credible evidence of either coffee drinking or knowledge of the coffee plant appears in the middle of the fifteenth century, in the

Kola nut use appears to have ancient origins. It is chewed in many West African cultures, in both private and social settings, to restore vitality and ease hunger pangs.[254]

The earliest evidence of

Xocolatl was introduced to

The leaves and stems of the yaupon holly (

Chemical identification, isolation, and synthesis

In 1819, the German chemist Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge isolated relatively pure caffeine for the first time; he called it "Kaffebase" (i.e., a base that exists in coffee).[260] According to Runge, he did this at the behest of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.[a][262] In 1821, caffeine was isolated both by the French chemist Pierre Jean Robiquet and by another pair of French chemists, Pierre-Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou, according to Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius in his yearly journal. Furthermore, Berzelius stated that the French chemists had made their discoveries independently of any knowledge of Runge's or each other's work.[263] However, Berzelius later acknowledged Runge's priority in the extraction of caffeine, stating:[264] "However, at this point, it should not remain unmentioned that Runge (in his Phytochemical Discoveries, 1820, pages 146–147) specified the same method and described caffeine under the name Caffeebase a year earlier than Robiquet, to whom the discovery of this substance is usually attributed, having made the first oral announcement about it at a meeting of the Pharmacy Society in Paris."

Pelletier's article on caffeine was the first to use the term in print (in the French form Caféine from the French word for coffee: café).[265] It corroborates Berzelius's account:

Caffeine, noun (feminine). Crystallizable substance discovered in coffee in 1821 by Mr. Robiquet. During the same period – while they were searching for quinine in coffee because coffee is considered by several doctors to be a medicine that reduces fevers and because coffee belongs to the same family as the cinchona [quinine] tree – on their part, Messrs. Pelletier and Caventou obtained caffeine; but because their research had a different goal and because their research had not been finished, they left priority on this subject to Mr. Robiquet. We do not know why Mr. Robiquet has not published the analysis of coffee which he read to the Pharmacy Society. Its publication would have allowed us to make caffeine better known and give us accurate ideas of coffee's composition ...

Robiquet was one of the first to isolate and describe the properties of pure caffeine,[266] whereas Pelletier was the first to perform an elemental analysis.[267]

In 1827, M. Oudry isolated "théine" from tea,[268] but in 1838 it was proved by Mulder[269] and by Carl Jobst[270] that theine was actually the same as caffeine.

In 1895, German chemist

Historic regulations

Because it was recognized that coffee contained some compound that acted as a stimulant, first coffee and later also caffeine has sometimes been subject to regulation. For example, in the 16th century

at various times between 1756 and 1823.In 1911, caffeine became the focus of one of the earliest documented health scares, when the US government seized 40 barrels and 20 kegs of Coca-Cola syrup in Chattanooga, Tennessee, alleging the caffeine in its drink was "injurious to health".[280] Although the Supreme Court later ruled in favor of Coca-Cola in United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola, two bills were introduced to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1912 to amend the Pure Food and Drug Act, adding caffeine to the list of "habit-forming" and "deleterious" substances, which must be listed on a product's label.[281]

Society and culture

Regulations

The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (October 2020) |

United States

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers safe beverages containing less than 0.02% caffeine;

Consumption

Global consumption of caffeine has been estimated at 120,000 tonnes per year, making it the world's most popular psychoactive substance.[19] This amounts to an average of one serving of a caffeinated beverage for every person every day.[19] The consumption of caffeine has remained stable between 1997 and 2015.[286] Coffee, tea and soft drinks are the most important caffeine sources, with energy drinks contributing little to the total caffeine intake across all age groups.[286]

Religions

The Seventh-day Adventist Church asked for its members to "abstain from caffeinated drinks", but has removed this from baptismal vows (while still recommending abstention as policy).[287] Some from these religions believe that one is not supposed to consume a non-medical, psychoactive substance, or believe that one is not supposed to consume a substance that is addictive. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has said the following with regard to caffeinated beverages: "... the Church revelation spelling out health practices (Doctrine and Covenants 89) does not mention the use of caffeine. The Church's health guidelines prohibit alcoholic drinks, smoking or chewing of tobacco, and 'hot drinks' – taught by Church leaders to refer specifically to tea and coffee."[288]

Gaudiya Vaishnavas generally also abstain from caffeine, because they believe it clouds the mind and overstimulates the senses.[289] To be initiated under a guru, one must have had no caffeine, alcohol, nicotine or other drugs, for at least a year.[290]

Caffeinated beverages are widely consumed by Muslims. In the 16th century, some Muslim authorities made unsuccessful attempts to ban them as forbidden "intoxicating beverages" under Islamic dietary laws.[291][292]

Other organisms

The bacteria Pseudomonas putida CBB5 can live on pure caffeine and can cleave caffeine into carbon dioxide and ammonia.[293]

Caffeine is toxic to birds

Research

Caffeine has been used to double chromosomes in

See also

- Theobromine

- Theophylline

- Methylliberine

- Adderall

- Amphetamine

- Cocaine

- Nootropic

- Wakefulness-promoting agent

References

- Notes

- ^ In 1819, Runge was invited to show Goethe how belladonna caused dilation of the pupil, which Runge did, using a cat as an experimental subject. Goethe was so impressed with the demonstration that:

("After Goethe had expressed to me his greatest satisfaction regarding the account of the man [whom I'd] rescued [from serving in Napoleon's army] by apparent "black star" [i.e., amaurosis, blindness] as well as the other, he handed me a carton of coffee beans, which a Greek had sent him as a delicacy. 'You can also use these in your investigations,' said Goethe. He was right; for soon thereafter I discovered therein caffeine, which became so famous on account of its high nitrogen content.").[261]Nachdem Goethe mir seine größte Zufriedenheit sowol über die Erzählung des durch scheinbaren schwarzen Staar Geretteten, wie auch über das andere ausgesprochen, übergab er mir noch eine Schachtel mit Kaffeebohnen, die ein Grieche ihm als etwas Vorzügliches gesandt. "Auch diese können Sie zu Ihren Untersuchungen brauchen," sagte Goethe. Er hatte recht; denn bald darauf entdeckte ich darin das, wegen seines großen Stickstoffgehaltes so berühmt gewordene Coffein.

- Citations

- ^ "Caffeine". ChemSpider. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ S2CID 5572188.

Results: Of 49 symptom categories identified, the following 10 fulfilled validity criteria: headache, fatigue, decreased energy/ activeness, decreased alertness, drowsiness, decreased contentedness, depressed mood, difficulty concentrating, irritability, and foggy/not clearheaded. In addition, flu-like symptoms, nausea/vomiting, and muscle pain/stiffness were judged likely to represent valid symptom categories. In experimental studies, the incidence of headache was 50% and the incidence of clinically significant distress or functional impairment was 13%. Typically, onset of symptoms occurred 12–24 h after abstinence, with peak intensity at 20–51 h, and for a duration of 2–9 days.

- ^ PMID 24761279.

- ^ S2CID 19471083.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Caffeine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. 16 September 2013. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Military Nutrition Research (2001). "2, Pharmacology of Caffeine". Pharmacology of Caffeine. National Academies Press (US). Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Caffeine". Pubchem Compound. NCBI. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

Boiling Point

178 °C (sublimes)

Melting Point

238 DEG C (ANHYD) - ^ a b "Caffeine". ChemSpider. Royal Society of Chemistry. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

Experimental Melting Point:

234–236 °C Alfa Aesar

237 °C Oxford University Chemical Safety Data

238 °C LKT Labs [C0221]

237 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 14937

238 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 17008, 17229, 22105, 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

235.25 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

236 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 27892, 27893, 27894, 27895

235 °C Jean-Claude Bradley Open Melting Point Dataset 6603

234–236 °C Alfa Aesar A10431, 39214

Experimental Boiling Point:

178 °C (Sublimes) Alfa Aesar

178 °C (Sublimes) Alfa Aesar 39214 - ^ S2CID 14277779.

- PMID 24946991.

- PMID 24344115.

- PMID 20164566.

- ISBN 978-1-4641-8652-3.

- S2CID 235094871.

- ISBN 978-0-12-384953-3. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33758-1. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ PMID 23471406.

- ^ "Global coffee consumption, 2020/21". Statista. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Burchfield G (1997). Meredith H (ed.). "What's your poison: caffeine". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 26 July 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- PMID 24761274.

- ^ WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (PDF) (18th ed.). World Health Organization. October 2013 [April 2013]. p. 34 [p. 38 of pdf]. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- PMID 23465359.

- ^ S2CID 42527557.

- PMID 30573997.

- ^ PMID 26058966.

- ^ PMID 20664420.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Long-term caffeine use can lead to mild physical dependence. A withdrawal syndrome characterized by drowsiness, irritability, and headache typically lasts no longer than a day. True compulsive use of caffeine has not been documented.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (2013). "Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders" (PDF). American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

Substance use disorder in DSM-5 combines the DSM-IV categories of substance abuse and substance dependence into a single disorder measured on a continuum from mild to severe. ... Additionally, the diagnosis of dependence caused much confusion. Most people link dependence with "addiction" when in fact dependence can be a normal body response to a substance. ... DSM-5 will not include caffeine use disorder, although research shows that as little as two to three cups of coffee can trigger a withdrawal effect marked by tiredness or sleepiness. There is sufficient evidence to support this as a condition, however it is not yet clear to what extent it is a clinically significant disorder.

- PMID 7009653.

- PMID 20492310.

- .

- PMID 34946584.

- S2CID 28339831.

- S2CID 30123372.

- from the original on 22 April 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- S2CID 22983543.

- PMID 22253394.

- PMID 19915211.

- PMID 21127467.

- PMID 21154344.

- ^ a b "Caffeine: Summary of Clinical Use". IUPHAR Guide to Pharmacology. The International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- PMID 28050656.

- PMID 17904451.

- ^ S2CID 4334842.

- ^ PMID 20091514.

- PMID 25502052.

- S2CID 245773922.

- .

- ^ S2CID 29659192.

- S2CID 58539710.

- ^ Orthomolecular Psychiatry. 10 (3): 202–211. Archived(PDF) from the original on 6 October 2008.

- S2CID 17392483. Archived from the original(PDF) on 31 January 2021.

Caffeine does not usually affect performance in learning and memory tasks, although caffeine may occasionally have facilitatory or inhibitory effects on memory and learning. Caffeine facilitates learning in tasks in which information is presented passively; in tasks in which material is learned intentionally, caffeine has no effect. Caffeine facilitates performance in tasks involving working memory to a limited extent, but hinders performance in tasks that heavily depend on this, and caffeine appears to improve memory performance under suboptimal alertness. Most studies, however, found improvements in reaction time. The ingestion of caffeine does not seem to affect long-term memory. ... Its indirect action on arousal, mood and concentration contributes in large part to its cognitive enhancing properties.

- PMID 21531247.

- PMID 20464765.

- PMID 27612937.

- ^ S2CID 42039737.

- ^ PMID 24330705. Quote:

Caffeine-induced increases in performance have been observed in aerobic as well as anaerobic sports (for reviews, see [26,30,31])...

- S2CID 1884713.

- S2CID 7109086. Archived from the original(PDF) on 14 November 2020.

- PMID 23668655.

Amphetamines and caffeine are stimulants that increase alertness, improve focus, decrease reaction time, and delay fatigue, allowing for an increased intensity and duration of training ...

Physiologic and performance effects

• Amphetamines increase dopamine/norepinephrine release and inhibit their reuptake, leading to central nervous system (CNS) stimulation

• Amphetamines seem to enhance athletic performance in anaerobic conditions 39 40

• Improved reaction time

• Increased muscle strength and delayed muscle fatigue

• Increased acceleration

• Increased alertness and attention to task - S2CID 4515711. Archived from the original(PDF) on 15 February 2020.

- PMID 2912010.

- PMID 7486839.

- PMID 33255240.

- PMID 29527137.

- PMID 20019636.

- (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- S2CID 19331370.

- S2CID 46959658.

- PMID 30170953.

- ^ a b c d "Caffeine in Food". Health Canada. 6 February 2012. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ PMID 28438661.

- ^ PMID 30577937.

- from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- PMID 28603504.

- ISBN 978-1-58562-458-4.

- ^ PMID 21624882.

- ^ S2CID 220731550.

- ^ "Food Standards Agency publishes new caffeine advice for pregnant women". Archived from the original on 17 October 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- S2CID 6475015.

- PMID 21370398.

- PMID 25238871.

- PMID 26329421.

- PMID 25415846.

- PMID 10499460.

- PMID 1177987.

- ISBN 978-0-17-644107-4.

- ^ "Caffeine in the diet". MedlinePlus, US National Library of Medicine. 30 April 2013. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- PMID 11684540.

- S2CID 41617469. Archived from the original(PDF) on 8 March 2019.

- ^ Modulation of adenosine receptor expression in the proximal tubule: a novel adaptive mechanism to regulate renal salt and water metabolism Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 1 July 2008 295:F35-F36

- ^ O'Connor A (4 March 2008). "Really? The claim: caffeine causes dehydration". New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- S2CID 46352603.

- S2CID 378245.

- PMID 21346331.

- .

- S2CID 5364016.

- PMID 12204388.

- S2CID 45368729.

- PMID 20164571.

- S2CID 23377304.

- PMID 26518745.

- ISBN 978-1-118-84547-9.

Table 34-12... Caffeine Intoxication – Euphoria

- ISBN 9788024633787.

At a high dose, caffeine shows a euphoric effect.

- ISBN 978-0-08-091455-8.

Therefore, caffeine and other adenosine antagonists, while weakly euphoria-like on their own, may potentiate the positive hedonic efficacy of acute drug intoxication and reduce the negative hedonic consequences of drug withdrawal.

- ISBN 978-0-7295-3929-6.

In contrast to the amphetamines, caffeine does not cause euphoria, stereotyped behaviors or psychoses.

- ISBN 978-1-118-38578-4.

However, in contrast to other psychoactive stimulants, such as amphetamine and cocaine, caffeine and the other methylxanthines do not produce euphoria, stereotyped behaviors or psychotic like symptoms in large doses.

- ^ PMID 25089257.

- ^ Nestler EJ, Hymen SE, Holtzmann DM, Malenka RC. "16". Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

True compulsive use of caffeine has not been documented, and, consequently, these drugs are not considered addictive.

- PMID 24984891.

Academics and clinicians, however, have not yet reached consensus about the potential clinical importance of caffeine addiction (or 'use disorder')

- ISBN 978-1-118-75336-1.

- ^ Fishchman N, Mello N. Testing for Abuse Liability of Drugs in Humans (PDF). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration National Institute on Drug Abuse. p. 179. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2016.

- PMID 24459410.

DESPITE THE IMPORTANCE OF NUMEROUS PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS, AT ITS CORE, DRUG ADDICTION INVOLVES A BIOLOGICAL PROCESS: the ability of repeated exposure to a drug of abuse to induce changes in a vulnerable brain that drive the compulsive seeking and taking of drugs, and loss of control over drug use, that define a state of addiction. ... A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type NAc neurons increases an animal's sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement

- ISBN 978-0-12-398361-9. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

Astrid Nehlig and colleagues present evidence that in animals caffeine does not trigger metabolic increases or dopamine release in brain areas involved in reinforcement and reward. A single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) assessment of brain activation in humans showed that caffeine activates regions involved in the control of vigilance, anxiety, and cardiovascular regulation but did not affect areas involved in reinforcement and reward.

- PMID 20623930.

Caffeine is not considered addictive, and in animals it does not trigger metabolic increases or dopamine release in brain areas involved in reinforcement and reward. ... these earlier data plus the present data reflect that caffeine at doses representing about two cups of coffee in one sitting does not activate the circuit of dependence and reward and especially not the main target area, the nucleus accumbens. ... Therefore, caffeine appears to be different from drugs of dependence like cocaine, amphetamine, morphine, and nicotine, and does not fulfil the common criteria or the scientific definitions to be considered an addictive substance.42

- PMID 19428492.

Through these interactions, caffeine is able to directly potentiate dopamine neurotransmission, thereby modulating the rewarding and addicting properties of nervous system stimuli.

- ISBN 978-0-8493-7881-2.

The suggestion has also been made that a caffeine dependence syndrome exists ... In one controlled study, dependence was diagnosed in 16 of 99 individuals who were evaluated. The median daily caffeine consumption of this group was only 357 mg per day (Strain et al., 1994).

Since this observation was first published, caffeine addiction has been added as an official diagnosis in ICDM 9. This decision is disputed by many and is not supported by any convincing body of experimental evidence. ... All of these observations strongly suggest that caffeine does not act on the dopaminergic structures related to addiction, nor does it improve performance by alleviating any symptoms of withdrawal - ^ "ICD-10 Version:2015". World Health Organization. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 November 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

F15 Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of other stimulants, including caffeine ...

.2 Dependence syndrome

A cluster of behavioural, cognitive, and physiological phenomena that develop after repeated substance use and that typically include a strong desire to take the drug, difficulties in controlling its use, persisting in its use despite harmful consequences, a higher priority given to drug use than to other activities and obligations, increased tolerance, and sometimes a physical withdrawal state.

The dependence syndrome may be present for a specific psychoactive substance (e.g., tobacco, alcohol, or diazepam), for a class of substances (e.g., opioid drugs), or for a wider range of pharmacologically different psychoactive substances. [Includes:]

Chronic alcoholism

Dipsomania

Drug addiction - ^ ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ^ PMID 19428492.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-89042-556-5.

- ^ a b "ICD-11 – Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (2013). "Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders". American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ "Information about caffeine dependence". Caffeinedependence.org. Johns Hopkins Medicine. 9 July 2003. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ PMID 10049999.

- PMID 20182026.

- S2CID 8376733.

- PMID 19825397.

- ^ "Coffee and the Liver". British Liver Trust. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- S2CID 8820874.

- S2CID 5566177.

Dose-response analysis suggested that incidence of T2DM decreased ...14% [0.86 (0.82-0.91)] for every 200 mg/day increment in caffeine intake.

- PMID 32580456.

- PMID 22505763.

- S2CID 668498.

- OCLC 825047464.

- .

- ^ "Can Yerba Mate tea actually crush your afternoon fatigue? Here's what the science says". www.sciencefocus.com.

- ^ https://www.bizjournals.com/sanfrancisco/news/2021/02/26/a-coffee-that-wont-give-you-caffeine-jitters.html

- ^ "Suffering from caffeine crashes now you're back in the office? Here's what to do about it (no, you don't have to quit coffee forever)". Glamour UK. 13 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Caffeine (Systemic)". MedlinePlus. 25 May 2000. Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-8493-7102-8. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ a b "ICD-11 – Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- S2CID 84842436.

- ^ PMID 6520875.

- ^ PMID 30422505.

- ^ "Caffeine | C8H10N4O2". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1967.tb00034.x. Archived from the originalon 12 January 2012.

- PMID 30137774.

- ^ Carpenter M (18 May 2015). "Caffeine powder poses deadly risks". New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- PMID 7638557.

- ^ Cheston P, Smith L (11 October 2013). "Man died after overdosing on caffeine mints". The Independent. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Prynne M (11 October 2013). "Warning over caffeine sweets after father dies from overdose". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ "Caffeine Drug Monographs". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- S2CID 21764730.

- ^ PMID 11376916.

- PMID 12940502.

- S2CID 19827114.

- PMID 29025033.

- PMID 2184730.

- PMID 21302868.

- ISBN 978-0-323-08340-9.

- ^ "Vitamin B4". R&S Pharmchem. April 2011. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011.

- from the original on 20 March 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ S2CID 10511507. Archived from the original(PDF) on 15 November 2020.

- ^ S2CID 33159096.

On the other hand, our 'ventral shell of the nucleus accumbens' very much overlaps with the striatal compartment...

- ^ "World of Caffeine". World of Caffeine. 15 June 2013. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- S2CID 7578473.

- ^ "Caffeine". IUPHAR. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- PMID 19564396.

- ^ PMID 20182056.

By targeting A1-A2A receptor heteromers in striatal glutamatergic terminals and A1 receptors in striatal dopaminergic terminals (presynaptic brake), caffeine induces glutamate-dependent and glutamate-independent release of dopamine. These presynaptic effects of caffeine are potentiated by the release of the postsynaptic brake imposed by antagonistic interactions in the striatal A2A-D2 and A1-D1 receptor heteromers.

- ^ PMID 26051403.

- ^ PMID 26100888.

Adenosine A2A receptor (A2AR)-dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) heteromers are key modulators of striatal neuronal function. It has been suggested that the psychostimulant effects of caffeine depend on its ability to block an allosteric modulation within the A2AR-D2R heteromer, by which adenosine decreases the affinity and intrinsic efficacy of dopamine at the D2R.

- ^ PMID 26786412.

The striatal A2A-D2 receptor heteromer constitutes an unequivocal main pharmacological target of caffeine and provides the main mechanisms by which caffeine potentiates the acute and long-term effects of prototypical psychostimulants.

- PMID 20164566.

- S2CID 21528985. Archived from the original(PDF) on 25 February 2020.

- PMID 18568240.

- PMID 9927365.

- ^ PMID 15634873.

- PMID 2003276.

- PMID 23698772.

- ^ PMID 20859793.

- S2CID 24067050.

- S2CID 10502739.

- S2CID 12291731.

- PMID 13165929.

- PMID 17553397.

- PMID 23533801.

- ^ "Drug Interaction: Caffeine Oral and Fluvoxamine Oral". Medscape Multi-Drug Interaction Checker.

- ^ "Caffeine". The Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ "7-Methylxanthine". Inxight Drugs. Archived from the original on 24 August 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- S2CID 251281523.

- S2CID 27888650.

- PMID 21490707.

- ^ a b Susan Budavari, ed. (1996). The Merck Index (12th ed.). Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co., Inc. p. 268.

- PMID 22469138.

- ISBN 978-0-7614-2242-6.

- ISBN 978-1-58409-016-8.

- ^ Keskineva N. "Chemistry of Caffeine" (PDF). Chemistry Department, East Stroudsburg University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ^ "Caffeine biosynthesis". The Enzyme Database. Trinity College Dublin. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ^ "MetaCyc Pathway: caffeine biosynthesis I". MetaCyc database. SRI International. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-58829-173-8.

- ^ a b US patent 2785162, Swidinsky J, Baizer MM, "Process for the formylation of a 5-nitrouracil", published 12 March 1957, assigned to New York Quinine and Chemical Works, Inc.

- PMID 25190796.

- PMID 27638206.

- ^ Williams R (21 September 2016). "How Plants Evolved Different Ways to Make Caffeine". The Scientist.

- (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2012.

- Bristol University. Archivedfrom the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ a b c Senese F (20 September 2005). "How is coffee decaffeinated?". General Chemistry Online. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- PMID 17132260. Archived from the originalon 18 July 2008. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-692-77499-1.

- PMID 3193854.

- ^ Kennerly J (22 September 1995). "N Substituted Xanthines: A Caffeine Analog Information File". Archived from the original on 4 November 2015. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- PMID 20859796.

- ^ Plant Polyphenols: Synthesis, Properties, Significance. Richard W. Hemingway, Peter E. Laks, Susan J. Branham (page 263)

- ^ "28 Plants that Contain Caffeine". caffeineinformer.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- S2CID 42711016. Archived from the original(PDF) on 27 February 2019.

- .

- .

- S2CID 17751471.

- ISBN 978-0-429-12678-9.

- ^ "Caffeine Content of Food and Drugs". Nutrition Action Health Newsletter. Center for Science in the Public Interest. 1996. Archived from the original on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ a b "Caffeine Content of Beverages, Foods, & Medications". The Vaults of Erowid. 7 July 2006. Archived from the original on 10 June 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ "Caffeine Content of Drinks". Caffeine Informer. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ PMID 19007524.

- ^ a b Richardson B (2009). "Too Easy to be True. De-bunking the At-Home Decaffeination Myth". Elmwood Inn. Archived from the original on 27 December 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ "Traditional Yerba Mate in Biodegradable Bag". Guayaki Yerba Mate. Archived from the original on 29 June 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ hdl:10072/49194.

- .

- ^ a b "Caffeine". International Coffee Organization. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ^ a b "Coffee and Caffeine FAQ: Does dark roast coffee have less caffeine than light roast?". Archived from the original on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^ a b "All About Coffee: Caffeine Level". Jeremiah's Pick Coffee Co. Archived from the original on 18 March 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ^ .

- ^ "Nutrition and healthy eating". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ISSN 0925-1618.

- ^ Martinez-Carter K (9 April 2012). "Drinking mate in Buenos Aires". BBC. Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ISBN 9781594776625.

- ^ Smith S (18 October 2017). "Flavoured milk and iced coffee sales on the rise". The Weekly Times. News Corp. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- S2CID 22069829.

- ^ "Caffeine tablets or caplets". Cleveland Clinic. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-415-92723-9. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ "LeBron James Shills for Sheets Caffeine Strips, a Bad Idea for Teens, Experts Say". Abcnews.go.com. ABC News. 10 June 2011. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ Shute N (15 April 2007). "Over The Limit:Americans young and old crave high-octane fuel, and doctors are jittery". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014.

- ^ "F.D.A. Inquiry Leads Wrigley to Halt 'Energy Gum' Sales". New York Times. Associated Press. 8 May 2013. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ^ Alex Williams (22 July 2015). "Caffeine Inhalers Rush to Serve the Energy Challenged". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ "2012 – Breathable Foods, Inc. 3/5/12". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 8 May 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ Greenblatt M (20 February 2012). "FDA to Investigate Safety of Inhalable Caffeine". ABC News. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ "Food Additives & Ingredients > Caffeinated Alcoholic Beverages". fda.gov. Food and Drug Administration. 17 November 2010. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-313-28049-8.

- ISBN 978-0-88001-416-8.[page needed]

- ISBN 978-0-415-92723-9.

- ^ Meyers H (7 March 2005). ""Suave Molecules of Mocha" – Coffee, Chemistry, and Civilization". New Partisan. Archived from the original on 9 March 2005. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- JSTOR 4391682.

- ISBN 978-1-61779-802-3.

- ^ Bekele FL. "The History of Cocoa Production in Trinidad and Tobago" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ A primer on PEF's Priority Commodities: an Industry Study on Cacao (PDF). Peace and Equity Foundation (Report). Philippines. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8203-2696-2.

- PMID 22869743.

- ^ Runge FF (1820). Neueste phytochemische Entdeckungen zur Begründung einer wissenschaftlichen Phytochemie [Latest phytochemical discoveries for the founding of a scientific phytochemistry]. Berlin: G. Reimer. pp. 144–159. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ^ This account appeared in Runge's book Hauswirtschaftlichen Briefen (Domestic Letters [i.e., personal correspondence]) of 1866. It was reprinted in: Johann Wolfgang von Goethe with F.W. von Biedermann, ed., Goethes Gespräche, vol. 10: Nachträge, 1755–1832 (Leipzig, (Germany): F.W. v. Biedermann, 1896), pages 89–96; see especially page 95

- ISBN 978-0-415-92723-9.

- ^ Berzelius JJ (1825). Jahres-Bericht über die Fortschritte der physischen Wissenschaften von Jacob Berzelius [Annual report on the progress of the physical sciences by Jacob Berzelius] (in German). Vol. 4. p. 180:

Caféin ist eine Materie im Kaffee, die zu gleicher Zeit, 1821, von Robiquet und Pelletier und Caventou entdekt wurde, von denen aber keine etwas darüber im Drucke bekannt machte.

[Caffeine is a material in coffee, which was discovered at the same time, 1821, by Robiquet and [by] Pelletier and Caventou, by whom however nothing was made known about it in the press.] - ^ Berzelius JJ (1828). Jahres-Bericht über die Fortschritte der physischen Wissenschaften von Jacob Berzelius [Annual Report on the Progress of the Physical Sciences by Jacob Berzelius] (in German). Vol. 7. p. 270:

Es darf indessen hierbei nicht unerwähnt bleiben, dass Runge (in seinen phytochemischen Entdeckungen 1820, p. 146-7.) dieselbe Methode angegeben, und das Caffein unter dem Namen Caffeebase ein Jahr eher beschrieben hat, als Robiquet, dem die Entdeckung dieser Substanz gewöhnlich zugeschrieben wird, in einer Zusammenkunft der Societé de Pharmacie in Paris die erste mündliche Mittheilung darüber gab.

- ^ Pelletier PJ (1822). "Cafeine". Dictionnaire de Médecine (in French). Vol. 4. Paris: Béchet Jeune. pp. 35–36. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Robiquet PJ (1823). "Café". Dictionnaire Technologique, ou Nouveau Dictionnaire Universel des Arts et Métiers (in French). Vol. 4. Paris: Thomine et Fortic. pp. 50–61. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ Dumas P (1823). "Recherches sur la composition élémentaire et sur quelques propriétés caractéristiques des bases salifiables organiques" [Studies into the elemental composition and some characteristic properties of organic bases]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique (in French). 24: 163–191.

- ^ Oudry M (1827). "Note sur la Théine" [Note on Theine]. Nouvelle Bibliothèque Médicale (in French). 1: 477–479.

- .

- .

- ^ Fischer began his studies of caffeine in 1881; however, understanding of the molecule's structure long eluded him. In 1895 he synthesized caffeine, but only in 1897 did he finally fully determine its molecular structure.

- Fischer E (1881). "Ueber das Caffeïn" [On caffeine]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin (in German). 14: 637–644. from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- Fischer E (1881). "Ueber das Caffeïn. Zweite Mitteilung" [On caffeine. Second communication.]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin (in German). 14 (2): 1905–1915. from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- Fischer E (1882). "Ueber das Caffeïn. Dritte Mitteilung" [On caffeine. Third communication.]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin (in German). 15: 29–33. from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- Fischer E, Ach L (1895). "Synthese des Caffeïns" [Synthesis of caffeine]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin (in German). 28 (3): 3135–3143. from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- Fischer E (1897). "Ueber die Constitution des Caffeïns, Xanthins, Hypoxanthins und verwandter Basen" [On the constitution of caffeine, xanthin, hypoxanthin, and related bases.]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin (in German). 30: 549–559. from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ Théel H (1902). "Nobel Prize Presentation Speech". Archived from the original on 10 August 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-4051-5807-7.

- ^ Ágoston G, Masters B (2009). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. p. 138.

- ^ Hopkins K (24 March 2006). "Food Stories: The Sultan's Coffee Prohibition". Accidental Hedonist. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ "By the King. A PROCLAMATION FOR THE Suppression of Coffee-Houses". Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Pendergrast 2001, p. 13

- ^ Pendergrast 2001, p. 11

- ^ Bersten 1999, p. 53

- PMID 2010614.

- ^ "The Rise and Fall of Cocaine Cola". Lewrockwell.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ "CFR – Code of Federal Regulations Title 21". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 21 August 2015. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ Sanner A (19 July 2014). "Sudden death of Ohio teen highlights dangers of caffeine powder". The Globe and Mail. Columbus, Ohio: Phillip Crawley. The Associated Press. Archived from the original on 31 December 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ "Guidance on Highly Concentrated Caffeine in Dietary Supplements". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 16 April 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ PMID 28605236.

- ISBN 978-0-9820787-6-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Mormonism in the News: Getting It Right August 29". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. 2012. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ "If Krishna does not accept my Chocolates, Who should I offer them to?". Dandavats.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ISBN 978-1857437591.

- ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-5772-1.

- ^ "Newly Discovered Bacteria Lives on Caffeine". Blogs.scientificamerican.com. 24 May 2011. Archived from the original on 17 April 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Paul L. "Why Caffeine is Toxic to Birds". HotSpot for Birds. Advin Systems. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Caffeine". Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ Noever R, Cronise J, Relwani RA (29 April 1995). "Using spider-web patterns to determine toxicity". NASA Tech Briefs. 19 (4): 82. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- PMID 18464846.

Bibliography

- Bersten I (1999). Coffee, Sex & Health: A history of anti-coffee crusaders and sexual hysteria. Sydney: Helian Books. ISBN 978-0-9577581-0-0.

- Carpenter M (2015). Caffeinated: How Our Daily Habit Helps, Hurts, and Hooks Us. Plume. ISBN 978-0142181805.

- ISBN 978-1-58799-088-5.

- ISBN 9780593296905.

External links

- GMD MS Spectrum

- Caffeine: ChemSub Online

- Caffeine at The Periodic Table of Videos(University of Nottingham)