California Fur Rush

Before the 1849

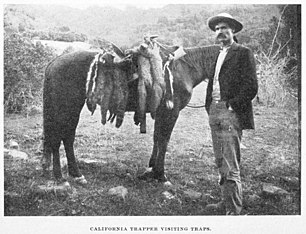

The massive increase of hunting and trapping in the 19th century caused the near extinction of many species in the state by 1911, including the California Golden Beaver and California Sea Otter.[3]

Coastal or maritime fur trade

The earliest record of fur being traded with Europeans in California was in 1733 of Spanish missionaries trading with tribes in upper and lower California for sea otter pelts. [3]

Just three years after

France sent

Robert Gray, captain of the ship Columbia rediscovered the mouth of the Columbia River in 1792 on his second voyage to the Pacific Coast.[9] Although the Spanish explorer Bruno de Heceta came to the river's mouth in 1775, no other explorer or fur trader had been able to find it since. By the 1790s American ships dominated the coastal fur trade south of Russian America.[4] In fact, Bostonian ships dominated the fur trade between California and China through the 1820s, when the sea otter supply was exhausted, and well before the first American mountain man, Jedediah Smith pioneered overland to California in pursuit of beaver pelts in 1826.[10]

The

The American ships Albatross under Nathan Winship O'Cain under his brother Jonathan Winship were sent from Boston in 1809 to establish a settlement on the Columbia River. In 1810, they met up with two other American ships at the Farallon Islands, the Mercury and the Isabella, and at least 30,000 seal skins were taken.[17][18] By 1822, the Farallons' fur seal hunt had diminished to 1,200 annually and the Russians suspended the hunt for two years.[16] Although American ships had already exploited the islands, the Russians maintained a sealing station in the Farallon Islands from 1812 to 1840, taking 1,200 to 1,500 fur seals annually, .[19] From 1824 on, the subsequent catch continued a steady decline until only about 500 could be taken annually; within the next few years, the seal was extirpated from the islands.[20]

The California fur trade ended as fur-bearers of all kinds were depleted in the first half of the nineteenth century. After sailing up and down the California coast, Richard Henry Dana recorded on May 8, 1836 at his last stop in San Diego how the trade in cattle hides had overtaken the fur trade: "Our forty thousand [cattle] hides and thirty thousand horns, besides several barrels of otter and beaver skins, were all stowed below, and the hatches calked down."[21] As the marine fur-bearers became too depleted to hunt and contracts with the Hudson's Bay Company provided food for the Alaskan settlements, the Russians abandoned Fort Ross in 1841.

By the end of the 19th century, California sea otters had been hunted to near extinction. The US government began to manage sea otter as a valuable natural resource in 1911. However, due to the previous two centuries of unregulated exploitation of the species, it was uncertain whether they would be able to revive the population.[3]

California fur-bearers today

In 2019, California State Legislature passed a bill banning the manufacturing, import, and sale of new fur products in the state. The law went into effect beginning January 1, 2023.[22]

California golden beaver are recolonizing the Bay Area by traversing north San Francisco Bay (from east to west) : Kirker Creek in the Dow Wetlands of

The spring 2019 sea otter survey counted 2,962 sea otters in the central California coast, down from an estimated pre-fur trade population of 16,000.

Both the California golden beaver and southern sea otter are considered keystone species, with a stabilizing and broad impact on their local ecosystems.

Northern fur seals (Callorhinus ursinus) were one of the first species to become protected through legislation with an international Fur Seal Treaty in 1911 which banned hunting fur seals in the ocean. The Marine Mammal Protection Act identifies the Northern Fur Seal population as depleted with the California population of fur seals estimated to be around 14,000. In 1966, the United States Congress passed the Fur Seal Act which banned the hunting of fur seals with the exception of substance hunting by Indigenous Americans. [29] The seals began to recolonize the Farallon Islands in 1996.[20]

In contrast, the Pacific Harbor seal (Phoca vitulina richardsi) is considered a species of least concern for endangerment of extinction. Their pelts were not nearly as popular as the otter or beaver. According to the Marine Mammal Center, the population of Pacific Harbor Seals off the coast of California is estimated to be around 34,000 individuals.[30]

See also

- Maritime fur trade

- List of watercourses in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Ecology of the San Francisco Estuary

- Martinez, California beavers

- North American beaver

- Beaver in the Sierra Nevada

- Sea otter

- Sea otter conservation

- California hide trade

References

- JSTOR 25462510. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ^ Skinner, John E. (1962). An Historical Review of the Fish and Wildlife Resources of the San Francisco Bay Area (The Mammalian Resources) (PDF). California Department of Fish and Game, Water Projects Branch Report no. 1. Sacramento, California: California Department of Fish and Game. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-11-07.

- ^ ISSN 0078-1304.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-87169-951-0.

- ^ a b Grinnell, Joseph; Joseph S. Dixon & Jean M. Linsdale (1937). Fur-bearing mammals of California; their natural history, systematic status, and relations to man. Berkeley, California: University of.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-2028-8.

- ^ Font, Pedro (Oct 1926). Edward F. O'Day (ed.). "The Founding of San Francisco". San Francisco Water. Spring Water Company. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- JSTOR 3633113.

- ISBN 978-0-87595-250-5.

- ^ Caughey, John Walton (1933). History of the Pacific Coast. John Walton Caughey. p. 195.

- ^ ISBN 0-559-89342-6.

- JSTOR 25178215.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-520-02806-7.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe; Alfred Bates; Ivan Petroff; William Nemos (1887). History of Alaska: 1730–1885. San Francisco, California: A. L. Bancroft & company. p. 482.

- ^ Stewart, Suzanne; Praetzellis, Aiden (November 2003). Archeological Research Issues for the Point Reyes National Seashore – Golden Gate National Recreation Area (PDF) (Report). Anthropological Studies Center, Sonoma State University. p. 335. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ ISBN 0-912006-42-0.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1886). Albatross, Log-book of a Voyage to the Northwest Coast in the Years 1809–1812, Kept by Wm. Gale, MS in History of California: 1801–1824. A.L. Bancroft & Company. pp. 93–94.

- ^ Hunt, Freeman (1846). "First Trading Settlement on the Columbia River". Merchants' Marine and Commercial Review. 14. New York: 202.

- ISBN 0-559-89342-6.

- ^ ISBN 0-942087-10-0.

- ^ Dana, Richard Henry (1869). Two Years Before the Mast. A Personal Narrative. Boston, Massachusetts: Fields, Osgood & Company. p. 324.

- ^ "Assembly Bill No. 44". California Legislative Information. October 12, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- Farnham, Thomas Jefferson (1857). Life, adventures, and travels in California. Blakeman & Co. p. 383.

- ^ Sue Dremann (November 4, 2022). "The beaver is back: Pair of the semiaquatic rodents spotted in Palo Alto". Palo Alto Weekly. Retrieved May 23, 2023.

- ^ doi:10.3133/ds1118.

- OCLC 30436543.

- ^ "Spring 2007 Mainland California Sea Otter Survey Results". U.S. Geological Survey. 30 May 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ Bodkin, J.L.; Estes, J.A.; Tinker., M.T. (January 2022). "History of Prior Sea Otter Translocation" (PDF). Elakha Alliance. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ "Northern Fur Seal". NOAA Fisheries. 2022-04-18. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ^ "Pacific Harbor Seal". The Marine Mammal Center. Retrieved 2023-03-13.