California Pacific International Exposition half dollar

United States | |

| Value | 50 cents (0.50 US dollars) |

|---|---|

| Mass | 12.5 g |

| Diameter | 30.61 mm (1.20 in) |

| Thickness | 2.15 mm (0.08 in) |

| Edge | Reeded |

| Composition |

|

| Silver | 0.36169 Seal of California |

| Designer | Robert Ingersoll Aitken |

| Design date | 1935 |

| Reverse | |

| |

| Design | California Tower and Chapel of St. Francis, Balboa Park, San Diego |

| Designer | Robert Ingersoll Aitken |

| Design date | 1935 |

The California Pacific International Exposition half dollar, sometimes called the California Pacific half dollar or the San Diego half dollar, is a

Legislation for the half dollar moved through Congress without opposition in early 1935, and Aitken was hired to design it. Once his creation was approved, the San Francisco Mint produced 250,000 coins, but expected sales did not materialize. Left with more than 180,000 pieces they could not sell, the Exposition Commission went back to Congress for further legislation so it could return the unsold pieces and have new coins, dated 1936, hoping for greater sales in the second year of the fair's run. Although the commission was successful in getting the legislation passed, it was less so in selling the coins, and 150,000 1936-dated pieces were returned to the Mint. The coins, of either date, sell in the low hundreds of dollars today.

Background and authorization

The California Pacific International Exposition was a world's fair held in San Diego's Balboa Park in 1935 and 1936. One of the largest expositions of its kind, it was held on 1,400 acres (570 ha) of land, and cost $20 million. The fair attracted some 3.75 million visitors during its two-year run.[1]

At that time, commemorative coins were not sold by the government—Congress, in authorizing legislation, usually designated an organization which had the exclusive right to purchase them at face value and sell them to the public at a premium.[2] In the case of the California Pacific Exposition half dollar, it was the California Pacific International Exposition Co.[3]

California's George Burnham introduced a bill for a California Pacific Exposition half dollar into the House of Representatives on February 19, 1935. It was referred to the Committee on Coinage, Weights, and Measures.[4] John J. Cochran of Missouri, acting chairman of that committee, reported back to the House on April 12 with the recommendation that it pass after small technical amendments were made. The bill called for the issuance of a maximum of 250,000 half dollars. Cochran noted that Congressman Burnham had appeared before the committee, representing that there would be no expense to the government, and sent a letter so stating (reproduced in the report). Burnham had also written that the Exposition had considerable participation by the federal government, and its officials expected seven to ten million people to attend.[5] The following day, Cochran had the bill considered by the House, which passed the recommended amendment and then the bill itself without any debate.[6]

The Senate received the bill on April 15, and referred it to the

Preparation and design

California Senator

Sculptor

Aitken's obverse shows elements of the

Numismatic author

Production, distribution, and collecting

250,132 coins were minted in San Francisco in August 1935. 132 were sent to Philadelphia and held for inspection and testing at the 1936 meeting of the

Although commemorative coin collecting (and investing) was becoming popular in 1935, the mintage of a quarter million coins, far in excess of some other issues of the era, meant investors were indifferent to the California Pacific issue. With sales of the 1935-S[a] half dollar coming to a standstill, the Exposition Commission was well aware of this problem. Thus, they sought relief from Congress in the form of an act allowing them to return unsold half dollars for new ones, dated 1936. Coin collectors would view this as a new variety and possibly buy both, and melting the returned coins would decrease the supply and (hopefully) increase the attractiveness of the remaining 1935-S specimens.[20][21]

At about this time [late 1935], commemorative coin collectors throughout the nation became coinage-figure conscious. Coinage figures for a while determined retail values. Large authorizations meant a tremendous floating supply of coins, which would have little value to the commemorative coin collector or to his new companion, the commemorative coin speculator.

—David M. Bullowa, The Commemorative Coinage of the United States 1892–1938 (1938), p. 124.

Accordingly, on January 6, 1936, Congressman Burnham introduced legislation to accomplish this.

The Senate committee reported on April 17, adding provisions requiring that the coins be dated 1936, regardless of when struck, and that they be produced at only one mint, chosen by the Director of the Mint, in line with other commemorative coin bills that committee had been reporting.[25] Early numismatic author David M. Bullowa noted these provisions, designed to prevent the creation of varieties, were thus inserted in a bill that itself created a new variety.[26] The Senate considered the bill on April 24, and it was amended and passed without debate or opposition.[27] As the two versions passed were not identical, the bill returned to the House of Representatives where, on April 27, that body at Burnham's motion, without debate or opposition, agreed to the Senate amendments.[28] President Roosevelt signed the bill on May 6.[29]

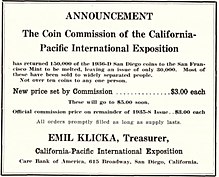

There was a spike in prices for many commemorative coins in 1936,[33] but due to the relatively high mintages of both the 1935-S and the 1936-D, the California Pacific coins sold badly, and when the Exposition closed in late 1936, fewer than 30,000 of the 1936-D had been sold.[34] On January 27, 1937, Davidson wrote to the Director of the Mint, Nellie Tayloe Ross, asking her to allow the return of some 150,000 coins for refund, the glut blamed on having a relatively short period to sell them. Once the Mint had granted permission, the Exposition Commission placed the 1935-S and 1936-D pieces it withheld from the melting pot on sale at $3 each.[35] Swiatek, in his 2012 volume on commemoratives, said the price increase was "to create the appearance of demand and future rarity. This didn't work."[32]

In 1938, Emil Klicka, treasurer of the Exposition, offered the 1936-D for sale at $1 each, with a limit of ten.[32] The 1935-S coins were available at $2. Large hoards of both dates were held by insiders for decades, including one holding of 31,050 of the 1935-S, amounting to nearly half the extant mintage. These were gradually dispersed from the 1960s to the 1980s.[36] In 1962, the 1935-S was worth $9 in uncirculated condition, and the 1936-D was worth $11.[37] The edition of the Red Book (A Guide Book of United States Coins) published in 2018 lists the 1935-S for between $100 and $160, depending on condition, with the 1936-D from between $100 and $225.[38] A near-pristine 1935-S sold at auction in 2014 for $4,994.[39]

Notes

References

- ^ a b c Swiatek & Breen, p. 38.

- ^ Slabaugh, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Flynn, p. 352.

- ^ 1935 Congressional Record, Vol. 81, Page 2259 (February 19, 1935) (subscription required)

- ^ 1935 House report, pp. 1–2.

- ^ 1935 Congressional Record, Vol. 81, Page 5606–5607 (April 13, 1935) (subscription required)

- ^ 1935 Congressional Record, Vol. 81, Page 5624 (April 15, 1935) (subscription required)

- ^ 1935 Senate report, pp. 1–2.

- ^ 1935 Congressional Record, Vol. 81, Page 6444 (April 26, 1935) (subscription required)

- ^ a b Bowers, p. 313.

- ^ Flynn, pp. 316, 322–323.

- ^ "Status of Commemorative Half Dollars of 1934". The Numismatist: 26. January 1935.

- ^ Taxay, pp. 172–174.

- ^ a b c d Bowers, p. 314.

- ^ a b Swiatek & Breen, p. 37.

- ^ Taxay, p. 172.

- ^ Taxay, p. 174.

- ^ Vermeule, p. 190.

- ^ a b Vermeule, p. 191.

- ^ Swiatek, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Slabaugh, p. 105.

- ^ 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 120 (January 6, 1936) (subscription required)

- ^ 1936 House report, p. 1.

- ^ 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 3799 (March 16, 1936) (subscription required)

- ^ 1936 Senate report, p. 1.

- ^ Bullowa, pp. 125–126.

- ^ 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 6063 (April 24, 1936) (subscription required)

- ^ 1936 Congressional Record, Vol. 82, Page 6243 (April 27, 1936) (subscription required)

- ^ Flynn, p. 354.

- ^ Flynn, p. 323.

- ^ Swiatek & Breen, p. 314.

- ^ a b c Swiatek, p. 261.

- ^ Bowers, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Bowers, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Flynn, p. 324.

- ^ Bowers, p. 315.

- ^ Slabaugh, p. 104.

- ^ Yeoman 2018, p. 1080.

- ^ Yeoman 2015, p. 1148.

Sources

- ISBN 978-0-943161-35-8.

- Bullowa, David M. (1938). "The Commemorative Coinage of the United States 1892–1938". Numismatic Notes and Monographs (83). New York: JSTOR 43607181.

- Flynn, Kevin (2008). The Authoritative Reference on Commemorative Coins 1892–1954. Roswell, Georgia: Kyle Vick. OCLC 711779330.

- Slabaugh, Arlie R. (1975). United States Commemorative Coinage (2nd ed.). Racine, Wisconsin: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-307-09377-6.

- Swiatek, Anthony (2012). Encyclopedia of the Commemorative Coins of the United States. Chicago: KWS Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9817736-7-4.

- Swiatek, Anthony; ISBN 978-0-668-04765-4.

- ISBN 978-0-668-01536-3.

- United States House of Representatives Committee on Coinage, Weights and Measures (April 12, 1935). Coinage of 50-cent pieces in connection with the California Pacific International Exposition to be held in San Diego, Calif., in 1935 and 1936. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

- United States House of Representatives Committee on Coinage, Weights and Measures (February 17, 1936). To authorize the recoinage of 50-cent pieces in connection with the California-Pacific International Exposition to be held in San Diego, Calif., in 1936. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

- United States Senate Committee on Banking and Currency (April 15, 1935). Coinage of 50-cent pieces in connection with the California Pacific International Exposition to be held in San Diego, Calif., in 1935 and 1936. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

- United States Senate Committee on Banking and Currency (April 17, 1936). Authorize recoinage of 50-cent pieces in connection with California-Pacific International Exposition, San Diego, Calif., 1936. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

- ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3.

- ISBN 978-0-7948-4307-6.

- Yeoman, R.S. (2018). A Guide Book of United States Coins (4th Mega ed.). Atlanta, Georgia: Whitman Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-0-7948-4580-3.

External links

Media related to California Pacific International Exposition half dollar at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to California Pacific International Exposition half dollar at Wikimedia Commons