Canada

Canada | |

|---|---|

| Motto: | |

| |

| Capital | Ottawa 45°24′N 75°40′W / 45.400°N 75.667°W |

| Largest city | Toronto |

| Official languages | |

| Demonym(s) | Canadian |

| Government | Federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

| Mary Simon | |

| Justin Trudeau | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| House of Commons | |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| July 1, 1867 | |

| December 11, 1931 | |

| April 17, 1982 | |

| Area | |

• Total area | 9,984,670 km2 (3,855,100 sq mi) (2nd) |

• Water (%) | 11.76 (2015)[2] |

• Total land area | 9,093,507 km2 (3,511,023 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2024 Q1 estimate | |

• 2021 census | |

• Density | 4.2/km2 (10.9/sq mi) (236th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2024) | low |

| HDI (2022) | very high (18th) |

| Currency | Canadian dollar ($) (CAD) |

| Time zone | UTC−3.5 to −8 |

• Summer (DST) | UTC−2.5 to −7 |

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's second-largest country by total area, with the world's longest coastline. Its border with the United States is the world's longest international land border. The country is characterized by a wide range of both meteorologic and geological regions. It is a sparsely inhabited country of 40 million people, the vast majority residing south of the 55th parallel in urban areas. Canada's capital is Ottawa and its three largest metropolitan areas are Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver.

Indigenous peoples have continuously inhabited what is now Canada for thousands of years. Beginning in the 16th century, British and French expeditions explored and later settled along the Atlantic coast. As a consequence of various armed conflicts, France ceded nearly all of its colonies in North America in 1763. In 1867, with the union of three British North American colonies through Confederation, Canada was formed as a federal dominion of four provinces. This began an accretion of provinces and territories and a process of increasing autonomy from the United Kingdom, highlighted by the Statute of Westminster, 1931, and culminating in the Canada Act 1982, which severed the vestiges of legal dependence on the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

Canada is a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy in the Westminster tradition. The country's head of government is the prime minister, who holds office by virtue of their ability to command the confidence of the elected House of Commons and is "called upon" by the governor general, representing the monarch of Canada, the ceremonial head of state. The country is a Commonwealth realm and is officially bilingual (English and French) in the federal jurisdiction. It is very highly ranked in international measurements of government transparency, quality of life, economic competitiveness, innovation, education and gender equality. It is one of the world's most ethnically diverse and multicultural nations, the product of large-scale immigration. Canada's long and complex relationship with the United States has had a significant impact on its history, economy, and culture.

A developed country, Canada has a high nominal per capita income globally and its advanced economy ranks among the largest in the world, relying chiefly upon its abundant natural resources and well-developed international trade networks. Canada is recognized as a middle power for its role in international affairs, with a tendency to pursue multilateral and international solutions. Canada's peacekeeping role during the 20th century has had a significant influence on its global image. Canada is part of multiple international organizations and forums.

Etymology

While a variety of theories have been postulated for the etymological origins of Canada, the name is now accepted as coming from the

From the 16th to the early 18th century, "Canada" referred to the part of New France that lay along the Saint Lawrence River.[10] In 1791, the area became two British colonies called Upper Canada and Lower Canada. These two colonies were collectively named the Canadas until their union as the British Province of Canada in 1841.[11]

Upon Confederation in 1867, Canada was adopted as the legal name for the new country at the London Conference and the word dominion was conferred as the country's title.[12] By the 1950s, the term Dominion of Canada was no longer used by the United Kingdom, which considered Canada a "realm of the Commonwealth".[13]

The Canada Act 1982, which brought the Constitution of Canada fully under Canadian control, referred only to Canada. Later that year, the name of the national holiday was changed from Dominion Day to Canada Day.[14] The term Dominion was used to distinguish the federal government from the provinces, though after the Second World War the term federal had replaced dominion.[15]

History

Indigenous peoples

The

The

Although not without conflict,

European colonization

It is believed that the first documented European to explore the east coast of Canada was

In 1583, Sir

The English established additional settlements in

British North America

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 established First Nation treaty rights, created the Province of Quebec out of New France, and annexed Cape Breton Island to Nova Scotia.[14] St John's Island (now Prince Edward Island) became a separate colony in 1769.[59] To avert conflict in Quebec, the British Parliament passed the Quebec Act 1774, expanding Quebec's territory to the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley.[60] More importantly, the Quebec Act afforded Quebec special autonomy and rights of self-administration at a time when the Thirteen Colonies were increasingly agitating against British rule.[61] It re-established the French language, Catholic faith, and French civil law there, staving off the growth of an independence movement in contrast to the Thirteen Colonies.[62] The Proclamation and the Quebec Act in turn angered many residents of the Thirteen Colonies, further fuelling anti-British sentiment in the years prior to the American Revolution.[14]

After the successful American War of Independence, the

The Canadas were the main front in the

The desire for

Confederation and expansion

Following three constitutional conferences, the British North America Act, 1867 officially proclaimed Canadian Confederation on July 1, 1867, initially with four provinces: Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick.[75][76] Canada assumed control of Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory to form the Northwest Territories, where the Métis' grievances ignited the Red River Rebellion and the creation of the province of Manitoba in July 1870.[77] British Columbia and Vancouver Island (which had been united in 1866) joined the confederation in 1871 on the promise of a transcontinental railway extending to Victoria in the province within 10 years,[78] while Prince Edward Island joined in 1873.[79] In 1898, during the Klondike Gold Rush in the Northwest Territories, Parliament created the Yukon Territory. Alberta and Saskatchewan became provinces in 1905.[79] Between 1871 and 1896, almost one quarter of the Canadian population emigrated south to the US.[80]

To open the West and encourage European immigration, the Government of Canada sponsored the construction of three transcontinental railways (including the Canadian Pacific Railway), passed the Dominion Lands Act to regulate settlement and established the North-West Mounted Police to assert authority over the territory.[81][82] This period of westward expansion and nation building resulted in the displacement of many Indigenous peoples of the Canadian Prairies to "Indian reserves",[83] clearing the way for ethnic European block settlements.[84] This caused the collapse of the Plains Bison in western Canada and the introduction of European cattle farms and wheat fields dominating the land.[85] The Indigenous peoples saw widespread famine and disease due to the loss of the bison and their traditional hunting lands.[86] The federal government did provide emergency relief, on condition of the Indigenous peoples moving to the reserves.[87] During this time, Canada introduced the Indian Act extending its control over the First Nations to education, government and legal rights.[88]

Early 20th century

Because Britain still maintained control of Canada's foreign affairs under the British North America Act, 1867, its declaration of war in 1914 automatically brought

The Great Depression in Canada during the early 1930s saw an economic downturn, leading to hardship across the country.[94] In response to the downturn, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in Saskatchewan introduced many elements of a welfare state (as pioneered by Tommy Douglas) in the 1940s and 1950s.[95] On the advice of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, war with Germany was declared effective September 10, 1939, by King George VI, seven days after the United Kingdom. The delay underscored Canada's independence.[90]

The first Canadian Army units arrived in Britain in December 1939. In all, over a million Canadians served in the armed forces during the

The Canadian economy boomed during the war as its industries manufactured military materiel for Canada, Britain, China, and the Soviet Union.[90] Despite another Conscription Crisis in Quebec in 1944, Canada finished the war with a large army and strong economy.[98]

Contemporary era

The financial crisis of the Great Depression led the Dominion of Newfoundland to relinquish responsible government in 1934 and become a Crown colony ruled by a British governor.[99] After two referendums, Newfoundlanders voted to join Canada in 1949 as a province.[100]

Canada's post-war economic growth, combined with the policies of successive Liberal governments, led to the emergence of a new

Finally, another series of constitutional conferences resulted in the Canada Act 1982, the patriation of Canada's constitution from the United Kingdom, concurrent with the creation of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[106][107][108] Canada had established complete sovereignty as an independent country under its own monarchy.[109][110] In 1999, Nunavut became Canada's third territory after a series of negotiations with the federal government.[111]

At the same time, Quebec underwent profound social and economic changes through the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, giving birth to a secular nationalist movement.[112] The radical Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) ignited the October Crisis with a series of bombings and kidnappings in 1970,[113] and the sovereigntist Parti Québécois was elected in 1976, organizing an unsuccessful referendum on sovereignty-association in 1980. Attempts to accommodate Quebec nationalism constitutionally through the Meech Lake Accord failed in 1990.[114] This led to the formation of the Bloc Québécois in Quebec and the invigoration of the Reform Party of Canada in the West.[115][116] A second referendum followed in 1995, in which sovereignty was rejected by a slimmer margin of 50.6 to 49.4 percent.[117] In 1997, the Supreme Court ruled unilateral secession by a province would be unconstitutional, and the Clarity Act was passed by Parliament, outlining the terms of a negotiated departure from Confederation.[114]

In addition to the issues of Quebec sovereignty, a number of crises shook Canadian society in the late 1980s and early 1990s. These included the explosion of

In 2011, Canadian forces participated in the NATO-led intervention into the

Geography

By total area (including its waters), Canada is the

Canada can be divided into seven physiographic regions: the

Climate

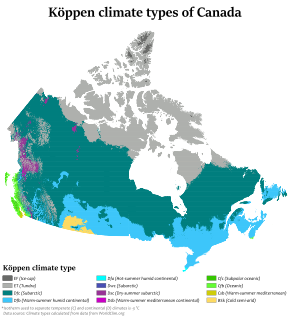

Average winter and summer high temperatures across Canada vary from region to region. Winters can be harsh in many parts of the country, particularly in the interior and Prairie provinces, which experience a continental climate, where daily average temperatures are near −15 °C (5 °F), but can drop below −40 °C (−40 °F) with severe wind chills.[141] In non-coastal regions, snow can cover the ground for almost six months of the year, while in parts of the north snow can persist year-round. Coastal British Columbia has a temperate climate, with a mild and rainy winter. On the east and west coasts, average high temperatures are generally in the low 20s °C (70s °F), while between the coasts, the average summer high temperature ranges from 25 to 30 °C (77 to 86 °F), with temperatures in some interior locations occasionally exceeding 40 °C (104 °F).[142]

Much of Northern Canada is covered by ice and permafrost. The future of the permafrost is uncertain because the Arctic has been warming at three times the global average as a result of climate change in Canada.[143] Canada's annual average temperature over land has risen by 1.7 °C (3.1 °F), with changes ranging from 1.1 to 2.3 °C (2.0 to 4.1 °F) in various regions, since 1948.[130] The rate of warming has been higher across the North and in the Prairies.[144] In the southern regions of Canada, air pollution from both Canada and the United States—caused by metal smelting, burning coal to power utilities, and vehicle emissions—has resulted in acid rain, which has severely impacted waterways, forest growth, and agricultural productivity in Canada.[145]

Biodiversity

Canada is divided into 15 terrestrial and five marine ecozones.[147] These ecozones encompass over 80,000 classified species of Canadian wildlife, with an equal number yet to be formally recognized or discovered.[148] Although Canada has a low percentage of endemic species compared to other countries,[149] due to human activities, invasive species, and environmental issues in the country, there are currently more than 800 species at risk of being lost.[150] About 65 percent of Canada's resident species are considered "Secure".[151] Over half of Canada's landscape is intact and relatively free of human development.[152] The boreal forest of Canada is considered to be the largest intact forest on Earth, with approximately 3,000,000 km2 (1,200,000 sq mi) undisturbed by roads, cities or industry.[153] Since the end of the last glacial period, Canada has consisted of eight distinct forest regions,[154] with 42 percent of its land area covered by forests (approximately 8 percent of the world's forested land).[155]

Approximately 12.1 percent of the nation's landmass and freshwater are

Government and politics

Canada is described as a "

At the federal level, Canada has been dominated by two relatively

Canada has a

The monarchy is the source of sovereignty and authority in Canada.[190][194][195] However, while the governor general or monarch may exercise their power without ministerial advice in certain rare crisis situations,[194] the use of the executive powers (or royal prerogative) is otherwise always directed by the Cabinet, a committee of ministers of the Crown responsible to the elected House of Commons and chosen and headed by the prime minister,[196] the head of government. To ensure the stability of government, the governor general will usually appoint as prime minister the individual who is the current leader of the political party that can obtain the confidence of a majority of members in the House of Commons.[197] The Prime Minister's Office (PMO) is thus one of the most powerful institutions in government, initiating most legislation for parliamentary approval and selecting for appointment by the Crown, besides the aforementioned, the governor general, lieutenant governors, senators, federal court judges, and heads of Crown corporations and government agencies.[194] The leader of the party with the second-most seats usually becomes the leader of the Official Opposition and is part of an adversarial parliamentary system intended to keep the government in check.[198]

The

Each of the 338

The Bank of Canada is the central bank of the country.[206] The minister of finance and minister of innovation, science, and industry use the Statistics Canada agency for financial planning and economic policy development.[207] The Bank of Canada is the sole authority authorized to issue currency in the form of Canadian bank notes.[208] The bank does not issue Canadian coins; they are issued by the Royal Canadian Mint.[209]

Law

The Constitution of Canada is the supreme law of the country and consists of written text and unwritten conventions.[210] The Constitution Act, 1867 (known as the British North America Act, 1867 prior to 1982), affirmed governance based on parliamentary precedent and divided powers between the federal and provincial governments.[211] The Statute of Westminster, 1931, granted full autonomy, and the Constitution Act, 1982, ended all legislative ties to Britain, as well as adding a constitutional amending formula and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[212] The Charter guarantees basic rights and freedoms that usually cannot be over-ridden by any government; though, a notwithstanding clause allows Parliament and the provincial legislatures to override certain sections of the Charter for a period of five years.[213]

Canada's judiciary plays an important role in interpreting laws and has the power to strike down acts of Parliament that violate the constitution. The Supreme Court of Canada is the highest court, final arbiter, and has been led since December 18, 2017, by Richard Wagner, the Chief Justice of Canada.[214] The governor general appoints the court's nine members on the advice of the prime minister and minister of justice.[215] The federal Cabinet also appoints justices to superior courts in the provincial and territorial jurisdictions.[216]

Common law prevails everywhere, except in Quebec, where civil law predominates.[217] Criminal law is solely a federal responsibility and is uniform throughout Canada.[218] Law enforcement, including criminal courts, is officially a provincial responsibility, conducted by provincial and municipal police forces.[219] In most rural and some urban areas, policing responsibilities are contracted to the federal Royal Canadian Mounted Police.[220]

Canadian Aboriginal law provides certain constitutionally recognized rights to land and traditional practices for Indigenous groups in Canada.[221] Various treaties and case laws were established to mediate relations between Europeans and many Indigenous peoples.[222] Most notably, a series of 11 treaties, known as the Numbered Treaties, were signed between the Indigenous peoples and the reigning monarch of Canada between 1871 and 1921.[223] These treaties are agreements between the Canadian Crown-in-Council, with the duty to consult and accommodate.[224] The role of Aboriginal law and the rights they support were reaffirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.[222] These rights may include provision of services, such as healthcare through the Indian Health Transfer Policy, and exemption from taxation.[225]

Foreign relations and military

Canada is recognized as a middle power for its role in global affairs with a tendency to pursue multilateral and international solutions.[227][228][229] Canada's foreign policy based on international peacekeeping and security is carried out through coalitions, international organizations, and the work of numerous federal institutions.[230][231] The strategy of the Canadian government's foreign aid policy reflects an emphasis to meet the Sustainable Development Goals, while also providing assistance in response to foreign humanitarian crises.[232] The Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) is tasked with gathering and analyzing intelligence to prevent threats such as terrorism, espionage, and foreign interference,[233] while the Communications Security Establishment (CSE) is focused on cyber security and protecting Canada's digital infrastructure.[233]

As of 2024, Canada's military had over 3000 personnel

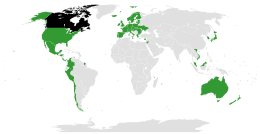

Canada is a

Provinces and territories

Canada is a federation composed of 10

The major difference between a Canadian province and a territory is that provinces receive their sovereignty from the Crown[262] and power and authority from the Constitution Act, 1867, whereas territorial governments have powers delegated to them by the Parliament of Canada[263] and the commissioners represent the King in his federal Council,[264] rather than the monarch directly. The powers flowing from the Constitution Act, 1867, are divided between the federal government and the provincial governments to exercise exclusively[265] and any changes to that arrangement require a constitutional amendment, while changes to the roles and powers of the territories may be performed unilaterally by the Parliament of Canada.[266]

Economy

Canada has a

Canada has a strong

Since the early 20th century, the growth of

Canada's economic integration with the United States has increased significantly since the

Canada is one of the few developed nations that are net exporters of energy.

Science and technology

In 2020, Canada spent approximately $41.9 billion on domestic

Canada's developments in science and technology include the creation of the modern alkaline battery,[308] the discovery of insulin,[309] the development of the polio vaccine,[310] and discoveries about the interior structure of the atomic nucleus.[311] Other major Canadian scientific contributions include the artificial cardiac pacemaker, mapping the visual cortex,[312][313] the development of the electron microscope,[314][315] plate tectonics, deep learning, multi-touch technology, and the identification of the first black hole, Cygnus X-1.[316] Canada has a long history of discovery in genetics, which include stem cells, site-directed mutagenesis, T-cell receptor, and the identification of the genes that cause Fanconi anemia, cystic fibrosis, and early-onset Alzheimer's disease, among numerous other diseases.[313][317]

The

Demographics

The

Canada's population density, at 4.2 inhabitants per square kilometre (11/sq mi), is among the lowest in the world.[324] Canada spans latitudinally from the 83rd parallel north to the 41st parallel north and approximately 95 percent of the population is found south of the 55th parallel north.[333] About 80 percent of the population lives within 150 kilometres (93 mi) of the border with the contiguous United States.[334] Canada is highly urbanized, with over 80 percent of the population living urban centres.[335] The most densely populated part of the country, accounting for nearly 50 percent, is the Quebec City–Windsor Corridor in Southern Quebec and Southern Ontario along the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River.[336][333]

The majority of Canadians (81.1 percent) live in family households, 12.1 percent report living alone, and those living with other relatives or unrelated persons reported at 6.8 percent.[337] Fifty-one percent of households are couples with or without children, 8.7 percent are single-parent households, 2.9 percent are multigenerational households, and 29.3 percent are single-person households.[337]

Rank

|

Name | Province

|

Pop.

|

Rank

|

Name | Province

|

Pop.

| ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Toronto | Ontario | 6,202,225 | 11 | London | Ontario | 543,551 | ||

| 2 | Montreal | Quebec | 4,291,732 | 12 | Halifax | Nova Scotia | 465,703 | ||

| 3 | Vancouver | British Columbia | 2,642,825 | 13 | St. Catharines–Niagara | Ontario | 433,604 | ||

| 4 | Ottawa–Gatineau | Ontario–Quebec | 1,488,307 | 14 | Windsor | Ontario | 422,630 | ||

| 5 | Calgary | Alberta | 1,481,806 | 15 | Oshawa | Ontario | 415,311 | ||

| 6 | Edmonton | Alberta | 1,418,118 | 16 | Victoria | British Columbia | 397,237 | ||

| 7 | Quebec City |

Quebec | 839,311 | 17 | Saskatoon | Saskatchewan | 317,480 | ||

| 8 | Winnipeg | Manitoba | 834,678 | 18 | Regina | Saskatchewan | 249,217 | ||

| 9 | Hamilton | Ontario | 785,184 | 19 | Sherbrooke | Quebec | 227,398 | ||

| 10 | Kitchener–Cambridge–Waterloo | Ontario | 575,847 | 20 | Kelowna | British Columbia | 222,162 | ||

Ethnicity

According to the

The country's ten largest self-reported specific ethnic or cultural origins in 2021 were Canadian[d] (accounting for 15.6 percent of the population), followed by English (14.7 percent), Irish (12.1 percent), Scottish (12.1 percent), French (11.0 percent), German (8.1 percent), Chinese (4.7 percent), Italian (4.3 percent), Indian (3.7 percent), and Ukrainian (3.5 percent).[345]

Of the 36.3 million people enumerated in 2021, approximately 25.4 million reported being "White", representing 69.8 percent of the population.[346] The Indigenous population representing 5 percent or 1.8 million individuals, grew by 9.4 percent compared to the non-Indigenous population, which grew by 5.3 percent from 2016 to 2021.[346] One out of every four Canadians or 26.5 percent of the population belonged to a non-White and non-Indigenous visible minority,[347][e] the largest of which in 2021 were South Asian (2.6 million people; 7.1 percent), Chinese (1.7 million; 4.7 percent), and Black (1.5 million; 4.3 percent).[349]

Between 2011 and 2016, the visible minority population rose by 18.4 percent.[350] In 1961, about 300,000 people, less than two percent of Canada's population, were members of visible minority groups.[351] The 2021 census indicated that 8.3 million people, or almost one-quarter (23.0 percent) of the population, reported themselves as being or having been a landed immigrant or permanent resident in Canada—above the 1921 census previous record of 22.3 percent.[352] In 2021, India, China, and the Philippines were the top three countries of origin for immigrants moving to Canada.[353]

Languages

A multitude of languages are used by Canadians, with

Quebec's 1974

Other provinces have no official languages as such, but French is used as a language of instruction, in courts, and for other government services, in addition to English. Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec allow for both English and French to be spoken in the provincial legislatures and laws are enacted in both languages. In Ontario, French has some legal status, but is not fully co-official.[360] There are 11 Indigenous language groups, composed of more than 65 distinct languages and dialects.[361] Several Indigenous languages have official status in the Northwest Territories.[362] Inuktitut is the majority language in Nunavut and is one of three official languages in the territory.[363]

Additionally, Canada is home to many sign languages, some of which are Indigenous.[364] American Sign Language (ASL) is used across the country due to the prevalence of ASL in primary and secondary schools.[365] Quebec Sign Language (LSQ) is used primarily in Quebec.[366]

Religion

Canada is religiously diverse, encompassing a wide range of beliefs and customs.

Rates of religious adherence have steadily decreased since the 1970s.

According to the 2021 census,

Health

Healthcare in Canada is delivered through the provincial and territorial systems of publicly funded health care, informally called Medicare.[383][384] It is guided by the provisions of the Canada Health Act of 1984[385] and is universal.[386] Universal access to publicly funded health services "is often considered by Canadians as a fundamental value that ensures national healthcare insurance for everyone wherever they live in the country."[387] Around 30 percent of Canadians' healthcare is paid for through the private sector.[388] This mostly pays for services not covered or partially covered by Medicare, such as prescription drugs, dentistry and optometry.[388] Approximately 65 to 75 percent of Canadians have some form of supplementary health insurance; many receive it through their employers or access secondary social service programs.[389][388]

In common with many other developed countries, Canada is experiencing an increase in healthcare expenditures due to a

In 2021, the

Education

Education in Canada is for the most part provided publicly, funded and overseen by federal, provincial, and local governments.[402] Education is within provincial jurisdiction and a province's curriculum is overseen by its government.[403][404] Education in Canada is generally divided into primary education, followed by secondary and post-secondary education. Education in both English and French is available in most places across Canada.[405] Canada has a large number of universities, almost all of which are publicly funded.[406] Established in 1663, Université Laval is the oldest post-secondary institution in Canada.[407] The largest university is the University of Toronto, with over 85,000 students.[408] Four universities are regularly ranked among the top 100 worldwide, namely University of Toronto, University of British Columbia, McGill University, and McMaster University, with a total of 18 universities ranked in the top 500 worldwide.[409]

According to a 2022 report by the OECD, Canada is one of the most educated countries in the world;[411][412] the country ranks first worldwide in the percentage of adults having tertiary education, with over 56 percent of Canadian adults having attained at least an undergraduate college or university degree.[413] Canada spends an average of 5.3 percent of its GDP on education.[414] The country invests heavily in tertiary education (more than US$20,000 per student).[415] As of 2022[update], 89 percent of adults aged 25 to 64 have earned the equivalent of a high-school degree, compared to an OECD average of 75 percent.[416]

The mandatory education age ranges between 5–7 to 16–18 years,[417] contributing to an adult literacy rate of 99 percent.[418] Just over 60,000 children are homeschooled in the country as of 2016. The Programme for International Student Assessment indicates Canadian students perform well above the OECD average, particularly in mathematics, science, and reading,[419][420] ranking the overall knowledge and skills of Canadian 15-year-olds as the sixth-best in the world, although these scores have been declining in recent years. Canada is a well-performing OECD country in reading literacy, mathematics, and science, with the average student scoring 523.7, compared with the OECD average of 493 in 2015.[421][422]

Culture

Canada's culture draws influences from its broad range of constituent nationalities and policies that promote a "just society" are constitutionally protected.[424][425][426] Since the 1960s, Canada has emphasized equality and inclusiveness for all its people.[427][428][429] The official state policy of multiculturalism is often cited as one of Canada's significant accomplishments[430] and a key distinguishing element of Canadian identity.[431][432] In Quebec, cultural identity is strong and there is a French Canadian culture that is distinct from English Canadian culture.[433] As a whole, Canada is in theory a cultural mosaic of regional ethnic subcultures.[434][435][436]

Canada's approach to governance emphasizing multiculturalism, which is based on selective

Historically, Canada has been influenced by

Symbols

Themes of nature, pioneers, trappers, and traders played an important part in the early development of Canadian symbolism.

Other prominent symbols include the national motto, "

Literature

Canadian literature is often divided into French- and English-language literatures, which are rooted in the literary traditions of France and Britain, respectively.[455] The earliest Canadian narratives were of travel and exploration.[456] This progressed into three major themes that can be found within historical Canadian literature: nature, frontier life, and Canada's position within the world, all three of which tie into the garrison mentality.[457] In recent decades, Canada's literature has been strongly influenced by immigrants from around the world.[458] By the 1990s, Canadian literature was viewed as some of the world's best.[459]

Numerous

Media

Canada's media is

Non-news media content in Canada, including film and television, is influenced both by local creators as well as by imports from the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and France.[473] In an effort to reduce the amount of foreign-made media, government interventions in television broadcasting can include both regulation of content and public financing.[474] Canadian tax laws limit foreign competition in magazine advertising.[475]

Visual arts

Art in Canada is marked by thousands of years of habitation by its Indigenous peoples,[477] and, in later times, artists have combined British, French, Indigenous, and American artistic traditions, at times embracing European styles while working to promote nationalism.[478] The nature of Canadian art reflects these diverse origins, as artists have taken their traditions and adapted these influences to reflect the reality of their lives in Canada.[479]

The Canadian government has played a role in the development of Canadian culture through the department of

Canadian visual art has been dominated by figures, such as painter Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven.[482] The latter were painters with a nationalistic and idealistic focus, who first exhibited their distinctive works in May 1920. Though referred to as having seven members, five artists—Lawren Harris, A. Y. Jackson, Arthur Lismer, J. E. H. MacDonald, and Frederick Varley—were responsible for articulating the group's ideas. They were joined briefly by Frank Johnston and commercial artist Franklin Carmichael. A. J. Casson became part of the group in 1926.[483] Associated with the group was another prominent Canadian artist, Emily Carr, known for her landscapes and portrayals of the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast.[484]

Music

Canadian music reflects a

Patriotic music in Canada dates back over 200 years. The earliest work of patriotic music in Canada, "The Bold Canadian", was written in 1812.[494] "The Maple Leaf Forever", written in 1866, was a popular patriotic song throughout English Canada and, for many years, served as an unofficial national anthem.[495] "O Canada" also served as an unofficial national anthem for much of the 20th century and was adopted as the country's official anthem in 1980.[496] Calixa Lavallée wrote the music, which was a setting of a patriotic poem composed by the poet and judge Sir Adolphe-Basile Routhier. The text was originally only in French before it was adapted into English in 1906.[497]

Sports

The roots of organized sports in Canada date back to the 1770s,[499] culminating in the development and popularization of the major professional games of ice hockey, lacrosse, curling, basketball, baseball, soccer, and Canadian football.[500] Canada's official national sports are ice hockey and lacrosse.[501] Other sports such as golf, volleyball, skiing, cycling, swimming, badminton, tennis, bowling, and the study of martial arts are all widely enjoyed at the youth and amateur levels.[502] Great achievements in Canadian sports are recognized by Canada's Sports Hall of Fame.[503] There are numerous other sport "halls of fame" in Canada, such as the Hockey Hall of Fame.[503]

Canada shares several major professional sports leagues with the United States.[504] Canadian teams in these leagues include seven franchises in the National Hockey League, as well as three Major League Soccer teams and one team in each of Major League Baseball and the National Basketball Association. Other popular professional competitions include the Canadian Football League, National Lacrosse League, the Canadian Premier League, and the various curling tournaments sanctioned and organized by Curling Canada.[505]

Canada has enjoyed success both

See also

- Index of Canada-related articles

- List of Canada-related topics by provinces and territories

- Outline of Canada

Notes

- ^ "Brokerage politics: A Canadian term for successful big tent parties that embody a pluralistic catch-all approach to appeal to the median Canadian voter ... adopting centrist policies and electoral coalitions to satisfy the short-term preferences of a majority of electors who are not located on the ideological fringe."[172][173] "The traditional brokerage model of Canadian politics leaves little room for ideology."[174][175][176][177]

- ^ "The Royal Canadian Navy is composed of approximately 8,400 full-time sailors and 5,100 part-time sailors. The Army is composed of approximately 22,800 full-time soldiers, 18,700 reservists, and 5,000 Canadian Rangers. The Royal Canadian Air Force is composed of approximately 13,000 Regular Force personnel and 2,400 Air Reserve personnel."[251]

- ^ All citizens of Canada are classified as "Canadians" as defined by Canada's nationality laws. "Canadian" as an ethnic group has since 1996 been added to census questionnaires for possible ancestral origin or descent. "Canadian" was included as an example on the English questionnaire and "Canadien" as an example on the French questionnaire.[342] "The majority of respondents to this selection are from the eastern part of the country that was first settled. Respondents generally are visibly European (Anglophones and Francophones) and no longer self-identify with their ethnic ancestral origins. This response is attributed to a multitude or generational distance from ancestral lineage."[343][344]

- ^ Indigenous peoples are not considered a visible minority in Statistics Canada calculations. Visible minorities are defined by Statistics Canada as "persons, other than aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour".[348]

- Catholic Church (29.9%), United Church (3.3%), Anglican Church (3.1%), Eastern Orthodoxy (1.7%), Baptistism (1.2%), Pentecostalism and other Charismatic (1.1%) Anabaptist (0.4%), Jehovah's Witness (0.4%), Latter Day Saints (0.2%), Lutheran (0.9%), Methodist and Wesleyan (Holiness) (0.3%), Presbyterian (0.8%), and Reformed (0.2%).[378] 7.6 percent simply identified as "Christians".[379]

References

- ^ "Royal Anthem". Government of Canada. August 11, 2017. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020.

- ^ "Surface water and surface water change". OECD. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ "Population estimates, quarterly". Statistics Canada. December 19, 2023. Archived from the original on March 29, 2024. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". February 9, 2022. Archived from the original on February 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 Edition. (Canada)". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. April 16, 2024. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- . Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. March 13, 2024. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-313-26257-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8020-8293-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-2938-6.

- ^ "An Act to Re-write the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada, and for the Government of Canada". J.C. Fisher & W. Kimble. 1841. p. 20.

- ISBN 978-90-04-17828-1.

- ISBN 978-0-85772-867-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-927164-1.

- ISBN 978-0-19-533535-4.

- ISBN 978-0-7867-2543-4.

- ISBN 978-1-317-34244-1.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-4456-4.

- ISBN 978-1-55365-259-5.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-4195-1.

- ISBN 978-0-8160-6770-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-85793-831-2.

- ^ "Census Program Data Viewer dashboard". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55111-873-4.

- ISBN 978-0-521-49666-7.

- ISBN 978-0-16-080388-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-1774-5.

- ISBN 978-0-7614-1637-1.

- ISBN 978-1-137-45236-8.

- ISBN 978-1-55263-633-6.

- ISBN 978-0-8032-2549-7.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-9227-5.

- ISBN 978-1-000-47233-2.

- ISBN 978-0-2280-0317-5.

- ISBN 978-0-7748-0581-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7735-9818-8.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-1386-7.

- ISBN 978-0-7748-5863-2.

- ^ a b "Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action" (PDF). National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. 2015. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2015.

- ^ "Principles respecting the Government of Canada's relationship with Indigenous peoples". Ministère de la Justice. July 14, 2017. Archived from the original on June 10, 2023.

- JSTOR community.15128627. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ^ Wallace, Birgitta (October 12, 2018). "Leif Eriksson". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-85109-818-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-313-02189-3.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-3553-1.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-6000-6.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-2495-4.

- ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0.

- ISBN 978-1-85109-437-0.

- ISBN 978-1-55081-225-1.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-9536-7.

- ISBN 978-0-690-00008-5.

- ISBN 978-1-85109-697-8.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-6977-1.

- ISBN 978-1-58465-427-8.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33046-9.

- S2CID 144657353.

- ^ "The Death of General Wolfe". National Gallery of Canada. Archived from the original on July 26, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- .

- ^ Hopkins, John Castell (1898). Canada: an Encyclopaedia of the Country: The Canadian Dominion Considered in Its Historic Relations, Its Natural Resources, its Material Progress and its National Development, by a Corps of Eminent Writers and Specialists. Linscott Publishing Company. p. 125.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-0403-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4497-2084-1.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-6892-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4516-8615-9.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-4360-3.

- ^ "Meeting Between Laura Secord and Lieut. Fitzgibbon, June 1813". Collection Search. July 13, 2023. Archived from the original on October 9, 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-55130-371-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-3447-2.

- ^ Gallagher, John A. (1936). "The Irish Emigration of 1847 and Its Canadian Consequences". CCHA Report: 43–57. Archived from the original on July 7, 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-8406-8.

- S2CID 147047853.

- ISBN 978-0-89862-030-6.

- ^ Farr, DML; Block, Niko (August 9, 2016). "The Alaska Boundary Dispute". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017.

- ^ "Territorial Evolution". Natural Resources Canada. September 12, 2016. Archived from the original on September 2, 2023.

- ISBN 978-90-5629-188-4.

- ISBN 978-0-87013-399-2.

- ISBN 978-0-920486-23-8.

- ^ "Railway History in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ a b "Building a nation". Canadian Atlas. Canadian Geographic. Archived from the original on March 3, 2006. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Denison, Merrill (1955). The Barley and the Stream: The Molson Story. McClelland & Stewart Limited. p. 8.

- ^ "Sir John A. Macdonald". Library and Archives Canada. 2008. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Cook, Terry (2000). "The Canadian West: An Archival Odyssey through the Records of the Department of the Interior". The Archivist. Library and Archives Canada. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ISBN 978-1-55458-422-2.

- ^ Gagnon, Erica. "Settling the West: Immigration to the Prairies from 1867 to 1914". Canadian Museum of Immigration. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ISBN 978-3-642-12194-4.

- ISBN 978-0-88977-296-0.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-4595-3.

- ISBN 978-1-4604-0696-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-8860-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7710-6514-9.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-8696-9.

- ^ a b McGonigal, Richard Morton (1962). "Intro". The Conscription Crisis in Quebec – 1917: a Study in Canadian Dualism. Harvard University Press.

- ISBN 978-1-55238-046-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-0555-1.

- S2CID 154091685.

- ISBN 978-1-78404-098-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-55002-547-7.

- ISBN 978-0-7748-1368-6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-927164-1.

- ISBN 978-1-4597-1884-5.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-8481-1.

- S2CID 143905306.

- doi:10.1037/h0084934.

- ^ Sarrouh, Elissar (January 22, 2002). "Social Policies in Canada: A Model for Development" (PDF). Social Policy Series, No. 1. United Nations. pp. 14–16, 22–37. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 17, 2010.

- ^ "The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms". Ministère de la Justice. March 15, 2021. Archived from the original on September 22, 2023.

- ^ "Proclamation of the Constitution Act, 1982". Government of Canada. May 5, 2014. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017.

- ^ "A statute worth 75 cheers". The Globe and Mail. March 17, 2009. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017.

- ^ Couture, Christa (January 1, 2017). "Canada is celebrating 150 years of... what, exactly?". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on February 10, 2017.

- ^ Trepanier, Peter (2004). "Some Visual Aspects of the Monarchical Tradition" (PDF). Canadian Parliamentary Review. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-55111-595-5.

- JSTOR 24674996.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-7314-7.

- S2CID 143725040.

- ^ .

- ^ Leblanc, Daniel (August 13, 2010). "A brief history of the Bloc Québécois". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-312-21134-9.

- ISBN 978-0-19-803150-5.

- ^ "Commission of Inquiry into the Investigation of the Bombing of Air India Flight 182". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Sourour, Teresa K (1991). "Report of Coroner's Investigation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 28, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "The Oka Crisis". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2000. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-2584-9.

- .

- S2CID 144463530.

- ISBN 978-1-137-27396-3.

- ^ Juneau, Thomas (2015). "Canada's Policy to Confront the Islamic State". Canadian Global Affairs Institute. Archived from the original on December 11, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)". Government of Canada. 2021. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021.

- ^ "Catholic group to release all records from Marievel, Kamloops residential schools". CTV News. June 25, 2021. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-9675-3.

- ISBN 978-1-4269-3393-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8160-5786-3.

- ^ "Geography". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on July 19, 2018. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ a b "Boundary Facts". International Boundary Commission. Archived from the original on May 20, 2023. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ Chase, Steven (June 10, 2022). "Canada and Denmark reach settlement over disputed Arctic island, sources say". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on June 12, 2022.

- ISBN 978-1-317-48718-0.

- ^ Canadian Geographic. Royal Canadian Geographical Society. 2008. p. 20.

- ^ "Physiographic Regions of Canada". The Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. September 12, 2016. Archived from the original on June 21, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-1672-4.

- ^ "Physical Components of Watersheds". The Atlas of Canada. December 5, 2012. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-927330-20-3.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-1179-5.

- ^ "Statistics, Regina SK". The Weather Network. Archived from the original on January 5, 2009. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- Environment Canada. September 25, 2013. Archivedfrom the original on May 18, 2015.

- ^ Bush, E.; Lemmen, D.S. (2019). "Canada's Changing Climate Report" (PDF). Government of Canada. p. 84. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 22, 2019.

- ^ Zhang, X.; Flato, G.; Kirchmeier-Young, M.; Vincent, L.; Wan, H.; Wang, X.; Rong, R.; Fyfe, J.; Li, G. (2019). Bush, E.; Lemmen, D.S. (eds.). "Changes in Temperature and Precipitation Across Canada; Chapter 4" (PDF). Canada's Changing Climate Report. Government of Canada. pp. 112–193. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 18, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-7748-4063-7.

- ^ "Terrestrial ecozones and ecoprovinces of Canada". Statistics Canada. January 12, 2018. Archived from the original on September 2, 2023.

- ^ "Introduction to the Ecological Land Classification (ELC) 2017". Statistics Canada. January 10, 2018. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020.

- ^ "Wild Species 2015: The General Status of Species in Canada" (PDF). National General Status Working Group: 1. Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council. 2016. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 27, 2021.

The new estimate indicates that there are about 80,000 known species in Canada, excluding viruses and bacteria

- ^ "Canada: Main Details". Convention on Biological Diversity. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ "COSEWIC Annual Report". Species at Risk Public Registry. 2019. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021.

- ^ "Wild Species 2000: The General Status of Species in Canada". Conservation Council. 2001. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021.

- ^ "State of Canada's Biodiversity Highlighted in New Government Report". October 22, 2010. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-470-94570-4.

- ISBN 978-0-7705-1198-2.

- ISBN 978-0-7748-2069-1.

- ^ a b "Canada's conserved areas". Environment and Climate Canada. 2020. Archived from the original on April 2, 2022.

- ^ "The Mountain Guide – Banff National Park" (PDF). Parks Canada. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2006.

- ISBN 978-1-84977-201-3.

- ^ "Algonquin Provincial Park Management Plan". Queen's Printer for Ontario. 1998. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021.

- ^ "Spotlight on Marine Protected Areas in Canada". Fisheries and Oceans Canada. December 13, 2017. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Scott Islands Marine National Widllife Area". Protected Planet. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ "Proposed Scott Islands Marine National Wildlife Area: regulatory strategy". Environment and Climate Change Canada. February 7, 2013. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021.

- ^ "UNESCO Biosphere Reserves of Canada". e CanadianBiosphere Reserves Association and the Canadian Commission for UNESCO. 2018. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. PDF Archived July 5, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "2021 Democracy Index" (PDF). Economist Intelligence Unit. 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 20, 2022.

- ISBN 978-1-55458-409-3.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-0121-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-3521-0.

- ISBN 978-0-385-67297-9.

- ISBN 978-1-55111-711-9.

- ISBN 978-1-317-36677-5.

- ISBN 978-1-5099-0788-5.

- ISBN 978-0-7748-2231-2.

- ISBN 978-0-19-533535-4.

- S2CID 154420921.

- ISBN 978-0-19-541806-4.

Two historically dominant political parties have avoided ideological appeals in favour of a flexible centrist style of politics that is often labelled brokerage politics

- ISBN 978-1-4426-0695-1.in an effort to defuse potential tensions.

Canada's party system has long been described as a "brokerage system" in which the leading parties (Liberal and Conservative) follow strategies that appeal across major social cleavages

- ISBN 978-1-4426-3521-0.

...most Canadian governments, especially in the federal sphere, have taken a moderate, centrist approach to decision making, seeking to balance growth, stability, and governmental efficiency and economy...

- ISBN 978-0-7748-2411-8.

- ^ Johnston, Richard (April 13, 2021). "The baffling history of Canada's party system". Policy Options. Archived from the original on December 9, 2022.

- ^ ISSN 2076-0760.

- ISBN 978-0-19-966399-6.

- ISBN 978-0-7748-3610-4.

- ^ "Election 2015 roundup". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on October 22, 2015.

- S2CID 145773856.

- from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ Geddes, John (February 8, 2022). "What's actually standing in the way of right-wing populism in Canada?". Macleans.ca. Archived from the original on October 31, 2022.

- ISBN 978-1-317-63444-7.

- Queen's Printer. March 29, 1867. Archivedfrom the original on February 3, 2010.

- ^ Smith, David E (June 10, 2010). "The Crown and the Constitution: Sustaining Democracy?" (PDF). The Crown in Canada: Present Realities and Future Options. Queen's University. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2010.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-662-46012-1. Archived from the original(PDF) on January 5, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-4597-4015-0.

- ^ "The Governor General of Canada: Roles and Responsibilities". Queen's Printer. Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-11-703249-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-662-39689-5. Archived from the original(PDF) on December 29, 2009. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Marleau, Robert; Montpetit, Camille. "House of Commons Procedure and Practice: Parliamentary Institutions". Queen's Printer. Archived from the original on August 28, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Edwards, Peter (November 4, 2015). "'A cabinet that looks like Canada:' Justin Trudeau pledges government built on trust". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on January 28, 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-55111-779-9.

- ^ "The Opposition in a Parliamentary System". Library of Parliament. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Restoring and modernizing the West Block". Public Services and Procurement Canada. August 15, 2023. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023.

- ^ McWhinney, Edward Watson (October 8, 2019). "Sovereignty". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023.

- ^ "About Elections and Ridings". Library of Parliament. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ O'Neal, Brian; Bédard, Michel; Spano, Sebastian (April 11, 2011). "Government and Canada's 41st Parliament: Questions and Answers". Library of Parliament. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-7047-4.

- ^ "Difference between Canadian Provinces and Territories". Intergovernmental Affairs Canada. 2010. Archived from the original on December 1, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

- ^ "Differences from Provincial Governments". Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories. 2008. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- JSTOR j.ctt9qf36m.

- ^ "About". Statistics Canada. 2014. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-134-65817-6.

- ISBN 978-1-4402-3129-2.

- ISBN 978-1-4597-3505-7.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-0871-9.

- ISBN 978-81-207-1937-8.

- ISBN 978-1-55239-085-6.

- ^ "Current and Former Chief Justices". Supreme Court of Canada. December 18, 2017. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018.

- S2CID 240317161.

- ISBN 978-0-13-792862-0.

- ISBN 978-90-411-9627-9.

- ISBN 978-1-55239-145-7.

- ^ "Who we are". Ontario Provincial Police. 2009. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-7619-2649-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7748-8023-7.

- ^ a b Patterson, Lisa Lynne (2004). Aboriginal roundtable on Kelowna Accord: Aboriginal policy negotiations 2004–2006 (PDF) (Report). 1. Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 26, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ "Treaty areas". Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. October 7, 2002. Archived from the original on January 7, 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-895830-65-1.

- ISBN 978-0-7766-0514-2.

- ^ a b "Diplomatic Missions and Consular Posts Accredited to Canada". GAC. June 10, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7748-4049-1.

- ISBN 978-83-7638-792-5.

- JSTOR 3233002. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-17-648249-7.

- ^ "Plans at a glance and operating context". Global Affairs Canada. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ "Canada and the Sustainable Development Goals". Social Development Canada. February 16, 2021. Archived from the original on November 21, 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-5443-5836-9.

- ^ "Canada and the United States". The Canadian Encyclopedia. June 11, 2020. Archived from the original on October 29, 2023.

- ^ Nord, D.C.; Weller, G.R. Canada and the United States: An Introduction to a Complex Relationship. p. 14.

- ISBN 978-3-030-05036-8.

- .

- ISSN 1180-3991.

- ISBN 978-0-7391-1493-3.

- ISBN 978-0-7146-8488-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7391-0480-4.

- ISBN 978-1-55111-816-1.

- ^ Dorn, Walter (March 17, 2013). "Canadian Peacekeeping No Myth" (PDF). Royal Canadian Military Institute. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-7748-1325-9.

- ISBN 978-0-385-67297-9.

- ISBN 978-0-7748-4016-3.

- ^ "RCAF 2014 Demo Jet revealed". Skies Mag. March 27, 2014. Archived from the original on October 10, 2023.

- ^ "Current operations list". National Defence. 2024.

- ^ "Strong, Secure, Engaged: Canada's Defence Policy". National Defence. September 22, 2017. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020.

- ^ "Canadian Armed Forces 101". National Defence. March 11, 2021. Archived from the original on October 30, 2022.

- ^ "About the Canadian Armed Forces". National Defence. March 11, 2021. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015.

- ^ "Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2022" (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. April 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ "International Organizations and Forums". Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. 2013. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ISBN 978-1-4597-0412-1.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-1108-5.

- ISBN 978-0-7397-1615-1.

- ^ Heritage, Canadian (October 23, 2017). "Human rights treaties". Canada.ca. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ "Canada Political Divisions" (PDF). Natural Resources Canada. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 15, 2023. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-6357-2.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-8853-0.

- ISBN 978-0-88975-215-3.

- ^ Jackson, Michael D. (1990). The Canadian Monarchy in Saskatchewan (2nd ed.). Regina: Queen's Printer for Saskatchewan. p. 14.

- ISBN 978-0-19-066482-4.

- ^ Commissioner of the Northwest Territories, Role of the Commissioner, Government of Northwest Territories, archived from the original on March 8, 2023, retrieved March 8, 2023

- ISBN 978-0-7748-0934-4.

- ISBN 978-0-7705-1742-7.

- ISBN 978-1-5063-6260-1.

- ISBN 9780191647703.

- ^ Diekmeyer, Peter (June 11, 2020). "Capitalism in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database". International Monetary Fund. April 2, 2019. Archived from the original on September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Evolution of the world's 25 top trading nations – Share of global exports of goods (%), 1978–2020". United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c "U.S.-Canada Trade Facts". Canada's State of Trade (20 ed.). Global Affairs Canada. 2021. Archived from the original on April 17, 2022. PDF version. Archived October 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Monthly Reports". World Federation of Exchanges. Archived from the original on February 18, 2020.as of November 2018[update]

- ISBN 978-1-4426-1625-7.

- ^ "Corruption Perceptions Index (latest)". Transparency International. January 31, 2023. Archived from the original on July 24, 2013.

- ISBN 978-1-351-57924-7.

- ^ "The Global Competitiveness Report 2019" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2019. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- ^ "Index of Economic Freedom". The Heritage Foundation. 2020. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ Shorrocks, Anthony; Davies, Jim; Lluberas, Rodrigo (October 2018). "Global Wealth Report". Credit Suisse. Archived from the original on July 18, 2017.

- ^ "Canada". OECD Better Life Index. 2021. Archived from the original on March 5, 2022.

- ^ "Prices - Housing prices". OECD. Archived from the original on August 11, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ^ a b "'Worst in the world': Here are all the rankings in which Canada is now last". National Post. August 11, 2022. Archived from the original on November 30, 2023.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-8020-3448-9. Archivedfrom the original on March 20, 2018.

- ^ "Employment by Industry". Statistics Canada. January 8, 2009. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-118-97933-4.

- ^ Vodden, K; Cunsolo, A. (2021). Warren, F.J.; Lulham, N. (eds.). "Rural and Remote Communities; Chapter 3" (PDF). Canada in a Changing Climate: National Issues Report. Government of Canada.

- ^ a b "Expand globally with Canada's free trade agreements". Trade Commissioner. December 3, 2020. Archived from the original on March 6, 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-4094-9852-0.

- ISBN 978-1-78347-668-8.

- ISBN 978-0-19-511739-4.

- ISBN 978-3-540-42634-9.

- ^ "CER – Market Snapshot: 25 Years of Atlantic Canada Offshore Oil & Natural Gas Production". Canada Energy Regulator. January 29, 2021. Archived from the original on November 28, 2022.

- ^ Monga, Vipal (January 13, 2022). "One of the World's Dirtiest Oil Patches Is Pumping More Than Ever". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 1, 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-317-07042-9.

- ^ "Trade Ranking Report: Agriculture" (PDF). FCC. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 3, 2019.

- ^ "Canada (CAN) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners". The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "The Atlas of Economic Complexity by @HarvardGrwthLab". The Atlas of Economic Complexity. Archived from the original on May 20, 2023. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "Mapping Canada's Top Manufacturing Industries". Industry Insider. January 22, 2015.

- ^ "Canada's oceans and the economic contribution of marine sectors". Statistics Canada. July 19, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2023.

- ^ "Gross domestic expenditures on research and development, 2020 (final), 2021 (preliminary) and 2022 (intentions)" (Press release). Statistics Canada. January 27, 2023.

- ^ "Canadian Nobel Prize in Science Laureates". Science.ca. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ "2022 tables: Countries/territories | 2022 tables | Countries/territories". Nature Index. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ "Top Technology Companies in Canada". World Top 25,000 Companies by market cap as on Dec 2022. January 1, 2020.

- ^ "Access to the Internet in Canada, 2020". Statistics Canada. May 31, 2021.

- ^ "Canadarm, Canadarm2, and Canadarm3 – A comparative table". Canadian Space Agency. December 31, 2002. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ "Lew Urry". Science.ca.

- ISBN 978-0-300-15359-0.

- ^ "Leone N. Farrell". Science.ca.

- ^ "Leon Katz". Science.ca.

- ^ Strauss, Evelyn (2005). "2005 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award". Lasker Foundation. Archived from the original on July 16, 2010. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- ^ a b "Top ten Canadian scientific achievements". GCS Research Society. 2015.

- ^ "James Hillier". Inventor of the Week. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on August 8, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- ^ Pearce, Jeremy (January 22, 2007). "James Hillier, 91, Dies; Co-Developed Electron Microscope". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014.

- S2CID 4222070.

- S2CID 4250632.

- ^ "Canadian Space Milestones". Canadian Space Agency. 2016. Archived from the original on October 8, 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-4381-1018-9.

- ISBN 978-981-4374-27-9.

- ^ "The Canadian Aerospace Industry praises the federal government for recognizing Space as a strategic capability for Canada". Newswire. March 11, 2010. Archived from the original on June 9, 2011.

- ISBN 978-3-319-40105-8.

- ^ "Section 4: Maps". Statistics Canada. February 11, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ^ a b Zimonjic, Peter (February 9, 2022). "Despite pandemic, Canada's population grows at fastest rate in G7: census". CBC News.

- ^ "Canada's population reaches 40 million". Statistics Canada. June 16, 2023. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-3793-4.

- ISBN 978-1-74104-571-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8047-8627-0.

- ISBN 978-1-55130-322-2.

- ^ Sangani, Priyanka (February 15, 2022). "Canada to take in 1.3 million immigrants in 2022–24". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on February 15, 2022.

- ^ Radford, Jynnah; Connor, Phillip (August 20, 2020). "Canada now leads the world in refugee resettlement, surpassing the U.S." Pew Research Center. Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-88975-246-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-64-10778-6.

- ISBN 978-0-88975-235-1.

- ^ "World Bank Open Data". World Bank Open Data (in Latin). Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-521-84287-7.

- ^ a b c d e "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population – Canada [Country]". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022.

- ^ "Census metropolitan area (CMA) and census agglomeration (CA)". Illustrated Glossary. November 15, 2017. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c "The Canadian census: A rich portrait of the country's religious and ethnocultural diversity". Statistics Canada. October 26, 2022. Archived from the original on December 27, 2023.

- ^ "Ethnic or cultural origin by gender and age: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". Statistics Canada. October 26, 2022.

- ^ "Canadian tops the more than 450 ethnic or cultural origins reported by the population of Canada". Statistics Canada. October 26, 2022. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ISBN 978-1-317-98108-4.

- ISBN 978-1-55130-936-1.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-3793-4.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population Profile table Canada [Country] Total – Ethnic or cultural origin for the population in private households – 25% sample data". Statistics Canada. October 26, 2022.

- ^ a b "The Daily — Indigenous population continues to grow and is much younger than the non-Indigenous population, although the pace of growth has slowed". Statistics Canada. September 21, 2022.

- ^ "Visible Minority". The Canadian Encyclopedia. October 27, 2022.

- ^ "Classification of visible minority". Statistics Canada. July 25, 2008. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011.

- ^ "The Daily — The Canadian census: A rich portrait of the country's religious and ethnocultural diversity". Statistics Canada. October 26, 2022.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2017. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017.

- ^ Pendakur, Krishna. "Visible Minorities and Aboriginal Peoples in Vancouver's Labour Market". Simon Fraser University. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "The Daily — Immigrants make up the largest share of the population in over 150 years and continue to shape who we are as Canadians". Statistics Canada. October 26, 2022.

- ^ "2021 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration". Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. March 15, 2022.

- ^ "2006 Census: The Evolving Linguistic Portrait, 2006 Census: Highlights". Statistics Canada, Dated 2006. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ "Official Languages and You". Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages. June 16, 2009. Archived from the original on October 27, 2009. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- S2CID 144320961.

- ISBN 978-1-78225-631-1.

- ISBN 978-3-11-018002-2.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-2960-1.

- ISBN 978-3-11-017687-2.

- ^ "Aboriginal languages". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-7748-0783-8.

- ISBN 978-0-85575-466-2.

- ^ "Sign languages". Canadian Association of the Deaf – Association des Sourds du Canada. 2015. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-61451-817-4.

- ISBN 978-0-88864-300-1.

- ^ "Freedom of Religion - by Marlene Hilton Moore". McMurtry Gardens of Justice. Retrieved June 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Cornelissen, Louis (October 28, 2021). "Religiosity in Canada and its evolution from 1985 to 2019". Statistics Canada.

- ISBN 978-0-7748-1497-3.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-0516-9.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-2955-7.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-1018-7.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-7194-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4443-1056-6.

- ISBN 978-1-317-46745-8.

- ISBN 978-1-894667-92-0.

- ISBN 978-1-134-72229-7.

- ^ "Religion by visible minority and generation status: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". Statistics Canada. October 26, 2022.

- ^ "Christianity". The Canadian Encyclopedia. October 27, 2022. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- ^ "Religions in Canada—Census 2011". Statistics Canada. May 8, 2013.

- ^ "Religion by visible minority and generation status: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". Statistics Canada. October 26, 2022.

- ^ "Sikh Heritage Month Act". laws.justice.gc.ca. January 14, 2020.

- ISBN 978-3-319-62346-7.

- ^ "Public vs. private health care". CBC News. December 1, 2006.

- ISBN 978-0-88890-219-1.

- ISBN 978-1-56720-513-8.

- ^ "17.2 Universality". The Health of Canadians – The Federal Role (Report). Parliament of Canada. Archived from the original on January 17, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4349-1768-3.

- ISBN 978-981-10-8441-6.

- ^ Weiss, Thomas G. (2017). "Canadian Male and Female Life Expectancy Rates by Province and Territory". Disabled World.

- ^ "Health Status of Canadians – How healthy are we? – Perceived health". Report of the Chief Public Health Officer. Public Health Agency of Canada. 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4963-9850-5.

- ^ "How Healthy are Canadians?". Public Health Agency of Canada. 2017.

- ^ "Health at a Glance 2019" (PDF). OECD. 2019.

- ^ "National Health Expenditure Trends". Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ "Health at a Glance 2017" (PDF). OECD. 2017.

- ^ "Health at a Glance: OECD Indicators by country". OECD. 2017.

- ^ .

- PMID 36849179.

- ^ "Taking the pulse: A snapshot of Canadian health care, 2023". Canadian Institute for Health Information. August 2, 2023. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ Scholey, Lucy (April 21, 2015). "2015 federal budget 'disappointing' for post-secondary students: CFS". Archived from the original on June 3, 2015.

- ^ Canada 1956 the Official Handbook of Present Conditions and Recent Progress. Canada Year Book Section Information Services Division Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1959.

- ISBN 978-1-4757-5504-6.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33617-1.

- ISBN 978-1-55339-506-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-3555-5.

- ISBN 978-1-61689-824-3.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2019: Canada". Shanghai Ranking. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ "British Columbia and Ontario saw the largest percentage point increases in degree holders from 2016 to 2021". Statistics Canada. November 30, 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "The Daily — Canada leads the G7 for the most educated workforce, thanks to immigrants, young adults and a strong college sector, but is experiencing significant losses in apprenticeship certificate holders in key trades". Statistics Canada. November 30, 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Key facts about Canada's competitiveness for foreign direct investment". GAC. January 17, 2022. Retrieved March 9, 2024. Raw data OECD

- ^ Education, Level Of. "Canada". Education GPS. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Canada Education spending, percent of GDP". TheGlobalEconomy.com. December 31, 1971. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "Financial and human resources invested in Education" (PDF). OECD. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- ^ "Education at a Glance". OECD. September 12, 2023. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Overview of Education in Canada". Council of Ministers of Education, Canada. Archived from the original on February 14, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ^ "Canada". The World Factbook. CIA. May 16, 2006.

- ^ "Comparing countries' and economies' performances" (PDF). OECD. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ "Canadian education among best in the world: OECD". CTV News. December 7, 2010. Archived from the original on May 28, 2013.

- ^ "PISA – Results in Focus" (PDF). OECD. 2015. p. 5.

- ^ "Canada – Student performance (PISA 2015)". OECD. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Kuitenbrouwer, Peter (August 19, 2010). "Where is the Monument to Multiculturalism?". National Post. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-1422-5.

- ISBN 978-0-17-650343-7.

- ISBN 978-0-7914-8584-2.

- S2CID 158927935.

- ISBN 978-0-385-67297-9.

- ISBN 978-94-6300-208-0.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-9220-9.

- ISBN 978-1-78699-382-3.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-2304-3.

- ISBN 978-1-56324-416-2.

- ^ Meister, Daniel R. "Racial Mosaic, The". McGill-Queen’s University Press. p. 234.

- S2CID 144187704.

- ^ "Cultural Diversity in Canada: The Social Construction of Racial Difference". Ministère de la Justice. February 24, 2003. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- S2CID 145773856.

- ISBN 978-0-8047-8735-2.

- ISBN 978-0-385-65985-7.

- ^ "Exploring Canadian values" (PDF). Nanos Research. October 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 5, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ "A literature review of Public Opinion Research on Canadian attitudes towards multiculturalism and immigration, 2006–2009". Government of Canada. 2011. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ "Focus Canada (Final Report)" (PDF). The Environics Institute. Queen's University. 2010. p. 4 (PDF page 8). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 4, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-3630-8.

- ISBN 978-1-55238-175-5.

- ^ Monaghan, David (2013). "The mother beaver". The House of Commons Heritage. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ "Canada in the Making: Pioneers and Immigrants". The History Channel. August 25, 2005.

- ISBN 9781442680616.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-660-18615-3.

- ^ "Maple Leaf Tartan becomes official symbol". Toronto Star. Toronto. March 9, 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-7504-3.

- ISBN 978-1-57113-359-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-17-672841-0.

- ISBN 978-1-55046-474-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4402-1915-3.

- ISBN 978-0-88984-283-0.

- ISBN 978-1-55111-049-3.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-0761-2.

- ISBN 978-90-04-48650-8.

- ISBN 978-1-61820-640-4.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-0761-2.

- ISBN 978-1-57113-139-3.

- ^ Broadview Anthology of British Literature. Vol. B (Concise ed.). Broadview Press. 2006. p. 1459. GGKEY:1TFFGS4YFLT.

- ISBN 978-0-7190-5231-6.

- ISBN 978-3-9855100-5-4.

- ^ Fry, H (2017). Disruption: Change and churning in Canada's media landscape (PDF) (Report). Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "Freedom of expression and media freedom". GAC. February 17, 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-77338-172-5.

- ISBN 978-1-55277-658-2.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-9519-0.

- ISBN 978-1-55238-224-0.

- ISBN 978-1-55238-224-0.

- ISBN 978-0-920380-81-9.

- ISBN 978-1-55266-447-6.

- ISBN 978-1-55238-222-6.

- ISBN 978-0-7748-2306-7.

- ^ "Tom Thomson, The Jack Pine, 1916–17". Art Canada Institute - Institut de l'art canadien. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ISBN 978-90-04-41426-6.

- JSTOR 41298655.

- ISBN 978-1-4426-6538-5.

- ^ as, for instance, in the following example of a show funded by the Government of Canada at the Peel Art Gallery Museum + Archives, Brampton:"Putting a spotlight on Canada's Artistic Heritage". Government of Canada. January 14, 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-00-041721-0.

- ISBN 978-0-7735-3817-7.

- ISBN 978-0-7710-6716-7.

- ISBN 978-1-55209-046-6.

- ^ ""O Canada"". The Canadian Encyclopedia. February 7, 2018. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ISBN 978-1-5013-4534-0.

- ^ The Canadian Communications Foundation. "The history of broadcasting in Canada". Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-317-65952-5.

- ^ "IFPI Global Music Report 2023" (PDF). p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-415-87560-8.

- ISBN 978-0-472-02241-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-9759-0.

- ISBN 978-1-135-94950-1.

- ISBN 978-0-19-976529-4.