Cancer epigenetics

Cancer epigenetics is the study of

Mechanisms

DNA methylation

In somatic cells, patterns of DNA methylation are in general transmitted to daughter cells with high fidelity.

Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoter regions can result in silencing of those genes. This type of epigenetic mutation allows cells to grow and reproduce uncontrollably, leading to tumorigenesis.

Hypomethylation of CpG dinucleotides in other parts of the genome leads to

The entire genome of a cancerous cell contains significantly less

CpG island methylation is important in regulation of gene expression, yet cytosine methylation can lead directly to destabilizing genetic mutations and a precancerous cellular state. Methylated cytosines make

Histone modification

In comparison to healthy cells, cancerous cells exhibit decreased monoacetylated and trimethylated forms of

Other histone marks associated with

Some research has focused on blocking the action of BRD4 on acetylated histones, which has been shown to increase the expression of the Myc protein, implicated in several cancers. The development process of the drug to bind to BRD4 is noteworthy for the collaborative, open approach the team is taking.[27]

The tumor suppressor gene p53 regulates DNA repair and can induce apoptosis in dysregulated cells. E Soto-Reyes and F Recillas-Targa elucidated the importance of the CTCF protein in regulating p53 expression.[28] CTCF, or CCCTC binding factor, is a zinc finger protein that insulates the p53 promoter from accumulating repressive histone marks. In certain types of cancer cells, the CTCF protein does not bind normally, and the p53 promoter accumulates repressive histone marks, causing p53 expression to decrease.[28]

Mutations in the epigenetic machinery itself may occur as well, potentially responsible for the changing epigenetic profiles of cancerous cells. The

MicroRNA gene silencing

In mammals,

Metabolic recoding of epigenetics in cancer

Dysregulation of metabolism allows tumor cells to generate needed building blocks as well as to modulate epigenetic marks to support cancer initiation and progression. Cancer-induced metabolic changes alter the epigenetic landscape, especially modifications on histones and DNA, thereby promoting malignant transformation, adaptation to inadequate nutrition, and metastasis. In order to satisfy the biosynthetic demands of cancer cells, metabolic pathways are altered by manipulating oncogenes and tumor suppressive genes concurrently.[38] The accumulation of certain metabolites in cancer can target epigenetic enzymes to globally alter the epigenetic landscape. Cancer-related metabolic changes lead to locus-specific recoding of epigenetic marks. Cancer epigenetics can be precisely reprogramed by cellular metabolism through 1) dose-responsive modulation of cancer epigenetics by metabolites; 2) sequence-specific recruitment of metabolic enzymes; and 3) targeting of epigenetic enzymes by nutritional signals.[38] In addition to modulating metabolic programming on a molecular level, there are microenvironmental factors that can influence and effect metabolic recoding. These influences include nutritional, inflammatory, and the immune response of malignant tissues.

MicroRNA and DNA repair

DNA damage appears to be the primary underlying cause of cancer.

Over-expression of certain miRNAs may directly reduce expression of specific DNA repair proteins. Wan et al.[44] referred to 6 DNA repair genes that are directly targeted by the miRNAs indicated in parentheses: ATM (miR-421), RAD52 (miR-210, miR-373), RAD23B (miR-373), MSH2 (miR-21), BRCA1 (miR-182) and P53 (miR-504, miR-125b). More recently, Tessitore et al.[45] listed further DNA repair genes that are directly targeted by additional miRNAs, including ATM (miR-18a, miR-101), DNA-PK (miR-101), ATR (miR-185), Wip1 (miR-16), MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 (miR-155), ERCC3 and ERCC4 (miR-192) and UNG2 (mir-16, miR-34c and miR-199a). Of these miRNAs, miR-16, miR-18a, miR-21, miR-34c, miR-125b, miR-101, miR-155, miR-182, miR-185 and miR-192 are among those identified by Schnekenburger and Diederich[46] as over-expressed in colon cancer through epigenetic hypomethylation. Over expression of any one of these miRNAs can cause reduced expression of its target DNA repair gene.

Up to 15% of the

In 28% of glioblastomas, the MGMT DNA repair protein is deficient but the MGMT promoter is not methylated.

High mobility group A (HMGA) proteins, characterized by an AT-hook, are small, nonhistone, chromatin-associated proteins that can modulate transcription. MicroRNAs control the expression of HMGA proteins, and these proteins (HMGA1 and HMGA2) are architectural chromatin transcription-controlling elements. Palmieri et al.[51] showed that, in normal tissues, HGMA1 and HMGA2 genes are targeted (and thus strongly reduced in expression) by miR-15, miR-16, miR-26a, miR-196a2 and Let-7a.

HMGA expression is almost undetectable in differentiated adult tissues but is elevated in many cancers. HGMA proteins are polypeptides of ~100 amino acid residues characterized by a modular sequence organization. These proteins have three highly positively charged regions, termed

HMGA2 protein specifically targets the promoter of ERCC1, thus reducing expression of this DNA repair gene.[55] ERCC1 protein expression was deficient in 100% of 47 evaluated colon cancers (though the extent to which HGMA2 was involved is unknown).[56]

Palmieri et al.[51] showed that each of the miRNAs that target HMGA genes are drastically reduced in almost all human pituitary adenomas studied, when compared with the normal pituitary gland. Consistent with the down-regulation of these HMGA-targeting miRNAs, an increase in the HMGA1 and HMGA2-specific mRNAs was observed. Three of these microRNAs (miR-16, miR-196a and Let-7a)[46][57] have methylated promoters and therefore low expression in colon cancer. For two of these, miR-15 and miR-16, the coding regions are epigenetically silenced in cancer due to histone deacetylase activity.[58] When these microRNAs are expressed at a low level, then HMGA1 and HMGA2 proteins are expressed at a high level. HMGA1 and HMGA2 target (reduce expression of) BRCA1 and ERCC1 DNA repair genes. Thus DNA repair can be reduced, likely contributing to cancer progression.[40]

DNA repair pathways

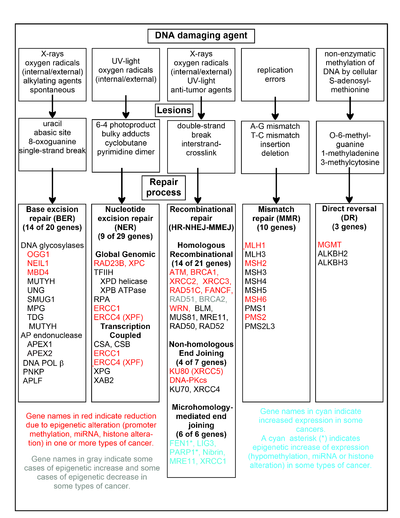

The chart in this section shows some frequent DNA damaging agents, examples of DNA lesions they cause, and the pathways that deal with these DNA damages. At least 169 enzymes are either directly employed in DNA repair or influence DNA repair processes.[59] Of these, 83 are directly employed in repairing the 5 types of DNA damages illustrated in the chart.

Some of the more well studied genes central to these repair processes are shown in the chart. The gene designations shown in red, gray or cyan indicate genes frequently epigenetically altered in various types of cancers. Wikipedia articles on each of the genes highlighted by red, gray or cyan describe the epigenetic alteration(s) and the cancer(s) in which these epimutations are found. Two broad experimental survey articles[60][61] also document most of these epigenetic DNA repair deficiencies in cancers.

Red-highlighted genes are frequently reduced or silenced by epigenetic mechanisms in various cancers. When these genes have low or absent expression, DNA damages can accumulate. Replication errors past these damages (see translesion synthesis) can lead to increased mutations and, ultimately, cancer. Epigenetic repression of DNA repair genes in accurate DNA repair pathways appear to be central to carcinogenesis.

The two gray-highlighted genes RAD51 and BRCA2, are required for homologous recombinational repair. They are sometimes epigenetically over-expressed and sometimes under-expressed in certain cancers. As indicated in the Wikipedia articles on RAD51 and BRCA2, such cancers ordinarily have epigenetic deficiencies in other DNA repair genes. These repair deficiencies would likely cause increased unrepaired DNA damages. The over-expression of RAD51 and BRCA2 seen in these cancers may reflect selective pressures for compensatory RAD51 or BRCA2 over-expression and increased homologous recombinational repair to at least partially deal with such excess DNA damages. In those cases where RAD51 or BRCA2 are under-expressed, this would itself lead to increased unrepaired DNA damages. Replication errors past these damages (see translesion synthesis) could cause increased mutations and cancer, so that under-expression of RAD51 or BRCA2 would be carcinogenic in itself.

Cyan-highlighted genes are in the microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) pathway and are up-regulated in cancer. MMEJ is an additional error-prone inaccurate repair pathway for double-strand breaks. In MMEJ repair of a double-strand break, an homology of 5-25 complementary base pairs between both paired strands is sufficient to align the strands, but mismatched ends (flaps) are usually present. MMEJ removes the extra nucleotides (flaps) where strands are joined, and then ligates the strands to create an intact DNA double helix. MMEJ almost always involves at least a small deletion, so that it is a mutagenic pathway.[62] FEN1, the flap endonuclease in MMEJ, is epigenetically increased by promoter hypomethylation and is over-expressed in the majority of cancers of the breast,[63] prostate,[64] stomach,[65][66] neuroblastomas,[67] pancreas,[68] and lung.[69] PARP1 is also over-expressed when its promoter region ETS site is epigenetically hypomethylated, and this contributes to progression to endometrial cancer,[70] BRCA-mutated ovarian cancer,[71] and BRCA-mutated serous ovarian cancer.[72] Other genes in the MMEJ pathway are also over-expressed in a number of cancers (see MMEJ for summary), and are also shown in blue.

Frequencies of epimutations in DNA repair genes

Deficiencies in DNA repair proteins that function in accurate DNA repair pathways increase the risk of mutation. Mutation rates are strongly increased in cells with mutations in DNA mismatch repair[73][74] or in homologous recombinational repair (HRR).[75] Individuals with inherited mutations in any of 34 DNA repair genes are at increased risk of cancer (see DNA repair defects and increased cancer risk).

In sporadic cancers, a deficiency in DNA repair is occasionally found to be due to a mutation in a DNA repair gene, but much more frequently reduced or absent expression of DNA repair genes is due to epigenetic alterations that reduce or silence gene expression. For example, for 113 colorectal cancers examined in sequence, only four had a

Epigenetic defects in DNA repair genes are frequent in cancers. In the table, multiple cancers were evaluated for reduced or absent expression of the DNA repair gene of interest, and the frequency shown is the frequency with which the cancers had an epigenetic deficiency of gene expression. Such epigenetic deficiencies likely arise early in carcinogenesis, since they are also frequently found (though at somewhat lower frequency) in the field defect surrounding the cancer from which the cancer likely arose (see Table).

| Cancer | Gene | Frequency in Cancer | Frequency in Field Defect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal | MGMT |

46% | 34% | [77] |

| Colorectal | MGMT | 47% | 11% | [78] |

| Colorectal | MGMT | 70% | 60% | [79] |

| Colorectal | MSH2 | 13% | 5% | [78] |

| Colorectal | ERCC1 | 100% | 40% | [56] |

| Colorectal | PMS2 | 88% | 50% | [56] |

| Colorectal | XPF | 55% | 40% | [56] |

| Head and Neck | MGMT | 54% | 38% | [80] |

| Head and Neck | MLH1 | 33% | 25% | [81] |

| Head and Neck | MLH1 | 31% | 20% | [82] |

| Stomach | MGMT | 88% | 78% | [83] |

| Stomach | MLH1 | 73% | 20% | [84] |

| Stomach | ERCC1 | 95-100% | 14-65% | [85] |

| Stomach | PMS2 | 95-100% | 14-60% | [85] |

| Esophagus | MLH1 | 77%–100% | 23%–79% | [86] |

It appears that cancers may frequently be initiated by an epigenetic reduction in expression of one or more DNA repair enzymes. Reduced DNA repair likely allows accumulation of DNA damages. Error prone

Cancers have high levels of genome instability, associated with a high frequency of mutations. A high frequency of genomic mutations increases the likelihood of particular mutations occurring that activate oncogenes and inactivate tumor suppressor genes, leading to carcinogenesis. On the basis of whole genome sequencing, cancers are found to have thousands to hundreds of thousands of mutations in their whole genomes.[87] (Also see Mutation frequencies in cancers.) By comparison, the mutation frequency in the whole genome between generations for humans (parent to child) is about 70 new mutations per generation.[88][89] In the protein coding regions of the genome, there are only about 0.35 mutations between parent/child generations (less than one mutated protein per generation).[90] Whole genome sequencing in blood cells for a pair of identical twin 100-year-old centenarians only found 8 somatic differences, though somatic variation occurring in less than 20% of blood cells would be undetected.[91]

While DNA damages may give rise to mutations through error prone translesion synthesis, DNA damages can also give rise to epigenetic alterations during faulty DNA repair processes.[41][42][92][93] The DNA damages that accumulate due to epigenetic DNA repair defects can be a source of the increased epigenetic alterations found in many genes in cancers. In an early study, looking at a limited set of transcriptional promoters, Fernandez et al.[94] examined the DNA methylation profiles of 855 primary tumors. Comparing each tumor type with its corresponding normal tissue, 729 CpG island sites (55% of the 1322 CpG sites evaluated) showed differential DNA methylation. Of these sites, 496 were hypermethylated (repressed) and 233 were hypomethylated (activated). Thus, there is a high level of epigenetic promoter methylation alterations in tumors. Some of these epigenetic alterations may contribute to cancer progression.

Epigenetic carcinogens

A variety of compounds are considered as epigenetic

Many

Cancer subtypes

Skin cancer

Prostate cancer

Prostate cancer kills around 35,000 men yearly, and about 220,000 men are diagnosed with prostate cancer per year, in North America alone.[104] Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-caused fatalities in men, and within a man's lifetime, one in six men will have the disease.[104] Alterations in histone acetylation and DNA methylation occur in various genes influencing prostate cancer, and have been seen in genes involved in hormonal response.[105] More than 90% of prostate cancers show gene silencing by CpG island hypermethylation of the GSTP1 gene promoter, which protects prostate cells from genomic damage that is caused by different oxidants or carcinogens.[106] Real-time methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) suggests that many other genes are also hypermethylated.[106] Gene expression in the prostate may be modulated by nutrition and lifestyle changes.[107]

Cervical cancer

The second most common malignant tumor in women is invasive

Leukemia

Recent studies have shown that the

Sarcoma

There are about 15,000 new cases of sarcoma in the US each year, and about 6,200 people were projected to die of sarcoma in the US in 2014.[112] Sarcomas comprise a large number of rare, histogenetically heterogeneous mesenchymal tumors that, for example, include chondrosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, osteosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, and (alveolar and embryonal) rhabdomyosarcoma. Several oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes are epigenetically altered in sarcomas. These include APC, CDKN1A, CDKN2A, CDKN2B, Ezrin, FGFR1, GADD45A, MGMT, STK3, STK4, PTEN, RASSF1A, WIF1, as well as several miRNAs.[113] Expression of epigenetic modifiers such as that of the BMI1 component of the PRC1 complex is deregulated in chondrosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma, and osteosarcoma, and expression of the EZH2 component of the PRC2 complex is altered in Ewing's sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. Similarly, expression of another epigenetic modifier, the LSD1 histone demethylase, is increased in chondrosarcoma, Ewing's sarcoma, osteosarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Drug targeting and inhibition of EZH2 in Ewing's sarcoma,[114] or of LSD1 in several sarcomas,[115] inhibits tumor cell growth in these sarcomas.

Lung Cancer

Lung cancer is the second most common type of cancer and leading cause of death in men and women in the United States, it is estimated that there is about 216,000 new cases and 160,000 deaths due to lung cancer.[116]

Initiation and progression of lung carcinoma is the result of the interaction between genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors. Most cases of lung cancer are because of genetic mutations in EGFR, KRAS, STK11 (also known as LKB1), TP53 (also known as p53), and CDKN2A (also known as p16 or INK4a)[117][118][119] with the most common type of lung cancer being an inactivation at p16. p16 is a tumor suppressor protein that occurs in mostly in humans the functional significance of the mutations was tested on many other species including mice, cats, dogs, monkeys and cows the identification of these multiple nonoverlapping clones was not entirely surprising since the reduced stringency hybridization of a zoo blot with the same probe also revealed 10-15 positive EcoRI fragments in all species tested.[120]

Identification methods

Previously, epigenetic profiles were limited to individual genes under scrutiny by a particular research team. Recently, however, scientists have been moving toward a more genomic approach to determine an entire genomic profile for cancerous versus healthy cells.[10]

Popular approaches for measuring CpG methylation in cells include:

- Bisulfite sequencing

- Combined bisulfite restriction analysis (COBRA)

- Methylation-specific PCR

- MethyLight

- Pyrosequencing

- Restriction landmark genomic scanning

- Arbitrary primed PCR

- HELP assay (HpaII tiny fragment enrichment by ligation-mediated PCR)

- Chromatin immunoprecipitation ChIP-Chip using antibodies specific for methyl-CpG binding domain proteins

- Methylated DNA immunoprecipitation Methyl-DIP

- Gene-expression profiles via mRNAlevels from cancer cell lines before and after treatment with a demethylating agent

Since bisulfite sequencing is considered the gold standard for measuring CpG methylation, when one of the other methods is used, results are usually confirmed using bisulfite sequencing[1]. Popular approaches for determining

- Mass spectrometry

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Diagnosis and prognosis

Researchers are hoping to identify specific epigenetic profiles of various types and subtypes of cancer with the goal of using these profiles as tools to diagnose individuals more specifically and accurately.

Another factor that will influence the treatment of patients is knowing how well they will respond to certain treatments. Personalized epigenomic profiles of cancerous cells can provide insight into this field. For example,

Therefore, if the gene encoding MGMT in cancer cells is hypermethylated and in effect silenced or repressed, the chemotherapeutic drugs that act by methylating guanine will be more effective than in cancer cells that have a functional MGMT enzyme.Epigenetic

Treatment

Epigenetic control of the proto-onco regions and the tumor suppressor sequences by conformational changes in histones plays a role in the formation and progression of cancer.[127] Pharmaceuticals that reverse epigenetic changes might have a role in a variety of cancers.[105][127][128]

Recently, it is evidently known that associations between specific cancer histotypes and epigenetic changes can facilitate the development of novel epi-drugs.[129] Drug development has focused mainly on modifying DNA methyltransferase, histone acetyltransferase (HAT) and histone deacetylase (HDAC).[130]

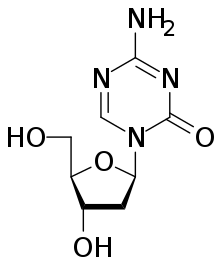

Drugs that specifically target the inverted methylation pattern of cancerous cells include the

Other pharmaceutical targets in research are histone lysine methyltransferases (KMT) and protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMT).[141] Preclinical study has suggested that lunasin may have potentially beneficial epigenetic effects.[142]

Epigenetic Therapy

Epigenetic therapy of cancer has shown to be a promising and possible treatment of cancerous cells. Epigenetic inactivation is an ideal target for cancerous cells because it targets genes imperative for controlling cell growth, specifically cancer cell growth. It is crucial for these genes to be reactivated in order to suppress tumor growth and sensitize the cells to cancer curing therapies.[143] Typical chemotherapy aims to kill and eliminate cancer cells in the body. Cancer initiated by genetic alterations of cells are typically permanent and nearly impossible to reverse, this differs from epigenetic cancer because the cancer causing epigenetic aberrations have the capability of being reversed, and the cells being returned to normal function. The ability for epigenetic mechanisms to be reversed is attributed to the fact that the coding of the genes being silenced through histone and DNA modification is not being altered.[144]

There are two primary types of epigenetic alterations in cancer cells, these are known as DNA methylation and Histone modification. It is the goal of epigenetic therapies to inhibit these alterations. DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs) and Histone Deacetylases (HDAC) are the primary catalyzes of the epigenetic modifications of cancer cells.[145] The goal for epigenetic therapies is to repress this methylation and reverse these modifications in order to create a new epigenome where cancer cells no longer thrive and tumor suppression is the new function. Synthetic drugs are used as tools in epigenetic therapies due to their ability to inhibit enzymes causing histone modifications and DNA methylations. Combination therapy is one method of epigenetic therapy which involves the use of more than one synthetic drug, these drugs include a low dose DNMT inhibitor as well as an HDAC inhibitor. Together, these drugs are able to target the linkage between DNA methylation and Histone modification.[146]

The goal of epigenetic therapies for cancer in relation to DNA methylation is to both decrease the methylation of DNA and in turn decrease the silencing of genes related to tumor suppression.[147] The term associated with decreasing the methylation of DNA will be known as hypomethylation. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has currently approved one hypomethylating agent which, through the conduction of clinical trials, has shown promising results when utilized to treat patients with Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS).[148] This hypomethylating agent is known as the doozy analogue of 5-azacytidine and works to promote hypomethylation by targeting all DNA methyltransferases for degradation.[147]

See also

References

- PMID 19752007.

- PMID 23539594.

- PMID 20885785.

- PMID 27493446.

- PMID 23096130.

- PMID 15775844.

- PMID 22735547.

- PMID 11782440.

- PMID 8790415.

- ^ S2CID 4801662.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-904455-88-2.

- ^ S2CID 2122000.

- PMID 22624715.

- ^ PMID 14627790.

- ^ S2CID 31655008.

- ^ S2CID 4424126.

- ^ PMID 15822191.

- ^ PMID 21941284.

- PMID 20421495.

- S2CID 4801662.

- PMID 23760024.

- ^ S2CID 27245550.

- PMID 27081402.

- PMID 19516333.

- S2CID 4409726.

- PMID 10954755.

- PMID 22874946.

- ^ S2CID 23983571.

- PMID 23372727.

- S2CID 9073684.

- PMID 35075221.

- PMID 19342239.

- PMID 18955434.

- PMID 16766263.

- PMID 17308079.

- ^ PMID 22277129.

- PMID 23342147.

- ^ PMID 29784032.

- PMID 18403632.

- ^ ISBN 978-953-51-1114-6.

- ^ PMID 18704159.

- ^ PMID 17616978.

- PMID 20420945.

- PMID 21741842.

- PMID 24616890.

- ^ PMID 22389639.

- ^ PMID 20351277.

- ^ PMID 15887099.

- ^ PMID 22570426.

- PMID 20150365.

- ^ PMID 22139073.

- S2CID 28903539.

- S2CID 34111491.

- PMID 12640109.

- PMID 14627817.

- ^ PMID 22494821.

- PMID 22771542.

- PMID 22096249.

- ^ Human DNA Repair Genes, 15 April 2014, MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Texas

- PMID 23249749.

- PMID 22286769.

- PMID 16012167.

- PMID 19010819.

- S2CID 22165252.

- PMID 15701830.

- PMID 24590400.

- S2CID 44644467.

- PMID 12651607.

- S2CID 22443138.

- PMID 23762867.

- PMID 24448423.

- PMID 23442605.

- PMID 9096356.

- PMID 16728433.

- PMID 11850397.

- PMID 15888787.

- PMID 16174854.

- ^ S2CID 8069716.

- S2CID 206950452.

- PMID 21147548.

- S2CID 8357370.

- PMID 21353335.

- PMID 19695681.

- PMID 23098428.

- ^ S2CID 212622031.

- PMID 22808291.

- PMID 23178448.

- PMID 20220176.

- PMID 23001126.

- PMID 22345605.

- PMID 24182360.

- PMID 20550933.

- PMID 24137009.

- PMID 21613409.

- PMID 9434858.

- S2CID 25874971.

- S2CID 9014237.

- S2CID 2260876.

- ^ "Vidaza (azacitidine for injectable suspension) package insert" (PDF). Pharmion Corporation. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 18 May 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2004.

- PMID 2005573.

- PMID 16690809.

- ^ PMID 22017262.

- PMID 30466474.

- ^ PMID 22252602.

- ^ PMID 15657340.

- ^ PMID 18948763.

- PMID 18559852.

- ^ PMID 21306759.

- S2CID 37705117.

- PMID 29879107.

- S2CID 54400632.

- ^ "Soft Tissue Sarcoma". National Cancer Institute. National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. January 1980.

- PMID 22126291.

- PMID 19289832.

- PMID 22245111.

- PMID 24077454.

- . Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- OCLC 1113687835.

- S2CID 17931210.

- OSTI 133832.

- S2CID 38574543.

- S2CID 40303322.

- PMID 15758010.

- PMID 11773279.

- PMID 16495912.

- S2CID 18279123.

- ^ PMID 20207580.

- PMID 20664922.

- PMID 27229488.

- PMID 18773966.

- S2CID 19854416.

- PMID 18841054.

- PMID 17219444.

- S2CID 42034181.

- S2CID 206871351.

- PMID 19230772.

- PMID 16960145.

- S2CID 19558322.

- S2CID 25070861.

- ^ "New Drug Application: Panobinostat" (PDF). Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 14 January 2015.

- PMID 20219369.

- ^ Galvez AF, Chen N, Macasieb J, de Lumen BO (October 15, 2001). "Chemopreventive Property of a Soybean Peptide (Lunasin) That Binds to Deacetylated Histones and Inhibits Acetylation". Cancer Research. 61.

- PMID 11927287.

- S2CID 4424126.

- S2CID 35003553.

- ^ Saleem, Mohammad (May 2015). "Epigenetic Therapy for Caner". Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 28 (3): 1023–1032.

- ^ a b aacrjournals.org https://aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article/13/6/1634/195851/DNA-Methylation-as-a-Therapeutic-Target-in-Cancer. Retrieved 2022-10-22.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - S2CID 9556660.