Canidae

| Canids | |

|---|---|

| |

| 10 of the 13 extant canid genera | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Infraorder: | Cynoidea |

| Family: | Canidae Fischer de Waldheim, 1817[2]

|

| Type genus | |

| Canis Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Subfamilies and extant genera | |

Canidae (

Canids are found on all continents except

Taxonomy

In the history of the carnivores, the family Canidae is represented by the two extinct subfamilies designated as Hesperocyoninae and Borophaginae, and the extant subfamily Caninae.

The cat-like

Phylogenetic relationships

This cladogram shows the phylogenetic position of canids within Caniformia, based on fossil finds:[1]

| Caniformia | |

Evolution

The Canidae today includes a diverse group of some 37 species ranging in size from the maned wolf with its long limbs to the short-legged bush dog. Modern canids inhabit forests, tundra, savannahs, and deserts throughout tropical and temperate parts of the world. The evolutionary relationships between the species have been studied in the past using morphological approaches, but more recently, molecular studies have enabled the investigation of phylogenetics relationships. In some species, genetic divergence has been suppressed by the high level of gene flow between different populations and where the species have hybridized, large hybrid zones exist.[8]

Eocene epoch

The canid family soon subdivided into three subfamilies, each of which diverged during the Eocene:

Oligocene epoch

By the

Miocene epoch

Around 8 Mya, the Beringian land bridge allowed members of the genus Eucyon a means to enter Asia from North America and they continued on to colonize Europe.[12]

Pliocene epoch

The

The formation of the Isthmus of Panama, about 3 Mya, joined South America to North America, allowing canids to invade South America, where they diversified. However, the most recent common ancestor of the South American canids lived in North America some 4 Mya and more than one incursion across the new land bridge is likely given the fact that more than one lineage is present in South America. Two North American lineages found in South America are the gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargentus) and the now-extinct dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus). Besides these, there are species endemic to South America: the maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus), the short-eared dog (Atelocynus microtis), the bush dog (Speothos venaticus), the crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous), and the South American foxes (Lycalopex spp.). The monophyly of this group has been established by molecular means.[12]

Pleistocene epoch

During the

By 0.3

In 2015, a study of mitochondrial genome sequences and whole-genome nuclear sequences of African and Eurasian canids indicated that extant wolf-like canids have colonized Africa from Eurasia at least five times throughout the Pliocene and Pleistocene, which is consistent with fossil evidence suggesting that much of African canid fauna diversity resulted from the immigration of Eurasian ancestors, likely coincident with Plio-Pleistocene climatic oscillations between arid and humid conditions. When comparing the African and Eurasian golden jackals, the study concluded that the African specimens represented a distinct monophyletic lineage that should be recognized as a separate species, Canis anthus (

Characteristics

Wild canids are found on every continent except Antarctica, and inhabit a wide range of different habitats, including

All canids have a similar basic form, as exemplified by the gray wolf, although the relative length of muzzle, limbs, ears, and tail vary considerably between species. With the exceptions of the bush dog, the raccoon dog and some domestic

All canids are digitigrade, meaning they walk on their toes. The tip of the nose is always naked, as are the cushioned pads on the soles of the feet. These latter consist of a single pad behind the tip of each toe and a more-or-less three-lobed central pad under the roots of the digits. Hairs grow between the pads and in the Arctic fox the sole of the foot is densely covered with hair at some times of the year. With the exception of the four-toed African wild dog (Lycaon pictus), five toes are on the forefeet, but the pollex (thumb) is reduced and does not reach the ground. On the hind feet are four toes, but in some domestic dogs, a fifth vestigial toe, known as a dewclaw, is sometimes present, but has no anatomical connection to the rest of the foot. In some species, slightly curved nails are non-retractile and more-or-less blunt[26] while other species have sharper, partially-retractile claws.[citation needed]

The

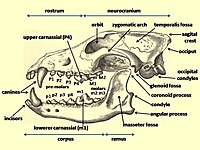

Dentition

Canids use their premolars for cutting and crushing except for the upper fourth premolar P4 (the upper carnassial) that is only used for cutting. They use their molars for grinding except for the lower first molar m1 (the lower carnassial) that has evolved for both cutting and grinding depending on the canid's dietary adaptation. On the lower carnassial, the

A study of the estimated bite force at the canine teeth of a large sample of living and fossil mammalian predators, when adjusted for their body mass, found that for

Most canids have 42

Life history

Social behavior

Almost all canids are social animals and live together in groups. In general, they are territorial or have a home range and sleep in the open, using their dens only for breeding and sometimes in bad weather.[35] In most foxes, and in many of the true dogs, a male and female pair work together to hunt and to raise their young. Gray wolves and some of the other larger canids live in larger groups called packs. African wild dogs have packs which may consist of 20 to 40 animals and packs of fewer than about seven individuals may be incapable of successful reproduction.[36] Hunting in packs has the advantage that larger prey items can be tackled. Some species form packs or live in small family groups depending on the circumstances, including the type of available food. In most species, some individuals live on their own. Within a canid pack, there is a system of dominance so that the strongest, most experienced animals lead the pack. In most cases, the dominant male and female are the only pack members to breed.[37]

Communication

Canids communicate with each other by

Reproduction

Canids as a group exhibit several reproductive traits that are uncommon among mammals as a whole. They are typically

During the proestral period, increased levels of

The size of a litter varies, with from one to 16 or more pups being born. The young are born small, blind and helpless and require a long period of parental care. They are kept in a den, most often dug into the ground, for warmth and protection.[26] When the young begin eating solid food, both parents, and often other pack members, bring food back for them from the hunt. This is most often vomited up from the adult's stomach. Where such pack involvement in the feeding of the litter occurs, the breeding success rate is higher than is the case where females split from the group and rear their pups in isolation.[46] Young canids may take a year to mature and learn the skills they need to survive.[47] In some species, such as the African wild dog, male offspring usually remain in the natal pack, while females disperse as a group and join another small group of the opposite sex to form a new pack.[48]

Canids and humans

One canid, the

The fact that wolves are pack animals with cooperative social structures may have been the reason that the relationship developed. Humans benefited from the canid's loyalty, cooperation, teamwork, alertness and tracking abilities, while the wolf may have benefited from the use of weapons to tackle larger prey and the sharing of food. Humans and dogs may have evolved together.[57]

Among canids, only the gray wolf has widely been known to prey on humans.[58][page needed] Nonetheless, at least two records of coyotes killing humans have been published,[59] and at least two other reports of golden jackals killing children.[60] Human beings have trapped and hunted some canid species for their fur and some, especially the gray wolf, the coyote and the red fox, for sport.[61] Canids such as the dhole are now endangered in the wild because of persecution, habitat loss, a depletion of ungulate prey species and transmission of diseases from domestic dogs.[62]

See also

References

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2012.

- ^ Fischer de Waldheim, G. 1817. Adversaria zoological. Memoir Societe Naturelle (Moscow) 5:368–428. p372

- ^ Canidae. Dictionary.com. The American Heritage Stedman's Medical Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Company. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Canidae (accessed: 16 February 2009).

- ^ Wang & Tedford 2008, pp. 181.

- ^ ISBN 978-0199545667.

- ^ Wang & Tedford 2008, pp. 182.

- S2CID 86755875.

- ^ Wayne, Robert K. "Molecular evolution of the dog family". Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Wang, Xiaoming (2008). "How Dogs Came to Run the World". Natural History Magazine. Vol. July/August. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- S2CID 12017658.

- ^ a b Martin, L.D. 1989. Fossil history of the terrestrial carnivora. Pages 536–568 in J.L. Gittleman, editor. Carnivore Behavior, Ecology, and Evolution, Vol. 1. Comstock Publishing Associates: Ithaca.

- ^ S2CID 20763999.

- S2CID 231604957.

- ^ Nowak, R.M. 1979. North American Quaternary Canis. Monograph of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 6:1 – 154.

- ^ a b Larson, Robert. "Wolves, coyotes and dogs (Genus Canis)". The Midwestern United States 16,000 years ago. Illinois State Museum. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ Nowak, R. (1992). "Wolves: The great travelers of evolution". International Wolf. 2 (4): 3–7.

- .

- PMID 22900047.

- PMID 26234211.

- ISBN 978-0-7614-2237-2.

- ISBN 1-886106-81-9

- ^ "ADW: Urocyon littoralis: Information". Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu. 28 November 1999. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Kauhala, K.; Saeki, M. (2004). Raccoon Dog«. Canid Species Accounts. IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. Pridobljeno 15 April 2009.

- ^ Ikeda, Hiroshi (August 1986). "Old dogs, new tricks: Asia's raccoon dog, a venerable member of the canid family is pushing into new frontiers". Natural History. 95 (#8): 40, 44.

- ^ "Raccoon dog – Nyctereutes procyonoides. WAZA – World Association of Zoos and Aquariums". Archived from the original on 10 April 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Mivart, St. George Jackson (1890). Dogs, Jackals, Wolves, and Foxes: A Monograph of the Canidae. London : R.H. Porter : Dulau. pp. xiv–xxxvi.

- ISBN 978-0-8018-8032-2.

- ISBN 978-0-8014-8493-3.

- ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

- ^ Wang & Tedford 2008, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Wang & Tedford 2008, pp. 74.

- ^ .

- ^ Cherin, Marco; Bertè, Davide Federico; Sardella, Raffaele; Rook, Lorenzo (2013). "Canis etruscus (Canidae, Mammalia) and its role in the faunal assemblage from Pantalla (Perugia, central Italy): comparison with the Late Villafranchian large carnivore guild of Italy". Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana. 52 (#1): 11–18.

- PMID 15817436.

- ISBN 978-0-906282-65-6.

- ^ McConnell, Patricia B. (31 August 2009). "Comparative canid behaviour". The other end of the leash. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Canidae: Coyotes, dogs, foxes, jackals, and wolves". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-323-15450-5.

- ISBN 0-8018-2525-3.

- ^ Van Heerden, Joseph. "The role of integumental glands in the social and mating behaviour of the hunting dog Lycaon pictus (Temminck, 1820)." (1981).

- ^ Fox, Michael W., and James A. Cohen. "Canid communication." How animals communicate (1977): 728-748.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-88977-154-3.

- ISBN 978-1-108-69949-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4665-1260-3.

- ISBN 978-0-521-45491-9.

- ISBN 978-1-84593-188-9.

- ISBN 0-937548-08-1

- ^ "Lycaon pictus". Animal Info: Endangered animals of the world. 26 November 2005. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- PMID 24453989.

- PMID 22615366.

- ^ "Domestication". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- .

- ^ Liane Giemsch, Susanne C. Feine, Kurt W. Alt, Qiaomei Fu, Corina Knipper, Johannes Krause, Sarah Lacy, Olaf Nehlich, Constanze Niess, Svante Pääbo, Alfred Pawlik, Michael P. Richards, Verena Schünemann, Martin Street, Olaf Thalmann, Johann Tinnes, Erik Trinkaus & Ralf W. Schmitz. "Interdisciplinary investigations of the late glacial double burial from Bonn-Oberkassel". Hugo Obermaier Society for Quaternary Research and Archaeology of the Stone Age: 57th Annual Meeting in Heidenheim, 7th – 11 April 2015, 36-37

- .

- (PDF) from the original on 4 January 2014.

- PMID 24453982.

- ^ Schleidt, Wolfgang M.; Shalter, Michael D. (2003). "Co-evolution of humans and canids: An alternative view of dog domestication: Homo homini lupus?" (PDF). Evolution and Cognition. 9 (1): 57–72. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2014.

- ISBN 0-521-81410-3.

- ^ "Coyote attacks: An increasing suburban problem" (PDF). San Diego County, California. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2006. Retrieved 19 August 2007.

- ^ "Canis aureus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved 31 July 2007.

- ^ "Fox hunting worldwide". BBC News. 16 September 1999. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- . Retrieved 11 November 2021.

Bibliography

- ISBN 978-0-231-13529-0.