Canis

| Canis | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st row: wolf (C. lupus), dog (C. familiaris); 2nd row: red wolf (C. rufus), eastern wolf (C. lycaon); 3rd row: coyote (C. latrans), golden jackal (C. aureus); 4th row: Ethiopian wolf (C. simensis), African wolf (C. lupaster). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Subfamily: | Caninae |

| Tribe: | Canini |

| Subtribe: | Canina |

| Genus: | Canis Linnaeus, 1758[2] |

| Type species | |

Canis familiaris

, 1758 | |

| Species | |

|

Extant:

Extinct:

| |

Canis is a

Taxonomy

The

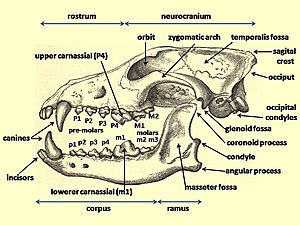

Canis is primitive relative to Cuon, Lycaon, and Xenocyon in its relatively larger canines and lack of such dental adaptations for hypercarnivory as m1–m2 metaconid and entoconid small or absent; M1–M2 hypocone small; M1–M2 lingual cingulum weak; M2 and m2 small, may be single-rooted; m3 small or absent; and wide palate.

The cladogram below is based on the DNA phylogeny of Lindblad-Toh et al. (2005),[8] modified to incorporate recent findings on Canis species,[9][10]

| Canis |

| |||||||||||||||

In 2019, a workshop hosted by the

Evolution

- See further: Evolution of the canids

The fossil record shows that

For Canis populations in the New World, Eucyon in North America gave rise to early North American Canis which first appeared in the Miocene (6 million YBP) in south-western United States and Mexico. By 5 million YBP the larger Canis lepophagus, ancestor of wolves and coyotes, appeared in the same region.[1]: p58

Around 5 million years ago, some of the Old World Eucyon evolved into the first members of Canis,

However, a 2021 genetic study of the

Dentition and biteforce

| Canid | Carnassial | Canine |

|---|---|---|

| Gray wolf | 131.6 | 127.3 |

| Dhole | 130.7 | 132.0 |

| African wild dog | 127.7 | 131.1 |

Greenland dog and dingo

|

117.4 | 114.3 |

| Coyote | 107.2 | 98.9 |

| Side-striped jackal | 93.0 | 87.5 |

| Golden jackal | 89.6 | 87.7 |

| Black-backed jackal | 80.6 | 78.3 |

A study of the estimated bite force at the canine teeth of a large sample of living and fossil mammalian predators, when adjusted for their body mass, found that for

Behavior

Description and sexual dimorphism

There is little variance among male and female canids. Canids tend to live as monogamous pairs. Wolves,

Mating behaviour

The genus Canis contains many different species and has a wide range of different mating systems that varies depending on the type of canine and the species.

Another study on

Canids also show a wide range of parental care and in 2018 a study showed that sexual conflict plays a role in the determination of intersexual parental investment.[29] The studied looked at coyote mating pairs and found that paternal investment was increased to match or near match the maternal investment. The amount of parental care provided by the fathers also was shown to fluctuated depending on the level of care provided by the mother.

Another study on parental investment showed that in free-ranging dogs, mothers modify their energy and time investment into their pups as they age.[30] Due to the high mortality of free-range dogs at a young age a mother's fitness can be drastically reduced. This study found that as the pups aged the mother shifted from high-energy care to lower-energy care so that they can care for their offspring for a longer duration for a reduced energy requirement. By doing this the mothers increasing the likelihood of their pups surviving infancy and reaching adulthood and thereby increase their own fitness.

A study done in 2017 found that aggression between male and female gray wolves varied and changed with age.[31] Males were more likely to chase away rival packs and lone individuals than females and became increasingly aggressive with age. Alternatively, females were found to be less aggressive and constant in their level of aggression throughout their life. This requires further research but suggests that intersexual aggression levels in gray wolves relates to their mating system.

Tooth breakage

Tooth breakage is a frequent result of carnivores' feeding behaviour.[32] Carnivores include both pack hunters and solitary hunters. The solitary hunter depends on a powerful bite at the canine teeth to subdue their prey, and thus exhibits a strong mandibular symphysis. In contrast, a pack hunter, which delivers many shallower bites, has a comparably weaker mandibular symphysis. Thus, researchers can use the strength of the mandibular symphysis in fossil carnivore specimens to determine what kind of hunter it was – a pack hunter or a solitary hunter – and even how it consumed its prey. The mandibles of canids are buttressed behind the carnassial teeth to crack bones with their post-carnassial teeth (molars M2 and M3). A study found that the modern gray wolf and the red wolf (C. rufus) possess greater buttressing than all other extant canids and the extinct dire wolf. This indicates that these are both better adapted for cracking bone than other canids.[33]

A study of nine modern carnivores indicate that one in four adults had suffered tooth breakage and that half of these breakages were of the canine teeth. The highest frequency of breakage occurred in the spotted hyena, which is known to consume all of its prey including the bone. The least breakage occurred in the African wild dog. The gray wolf ranked between these two.[32][34] The eating of bone increases the risk of accidental fracture due to the relatively high, unpredictable stresses that it creates. The most commonly broken teeth are the canines, followed by the premolars, carnassial molars, and incisors. Canines are the teeth most likely to break because of their shape and function, which subjects them to bending stresses that are unpredictable in direction and magnitude.[34] The risk of tooth fracture is also higher when taking and consuming large prey.[34][35]

In comparison to extant gray wolves, the extinct Beringian wolves included many more individuals with moderately to heavily worn teeth and with a significantly greater number of broken teeth. The frequencies of fracture ranged from a minimum of 2% found in the Northern Rocky Mountain wolf (Canis lupus irremotus) up to a maximum of 11% found in Beringian wolves. The distribution of fractures across the tooth row also differs, with Beringian wolves having much higher frequencies of fracture for incisors, carnassials, and molars. A similar pattern was observed in spotted hyenas, suggesting that increased incisor and carnassial fracture reflects habitual bone consumption because bones are gnawed with the incisors and then cracked with the carnassials and molars.[36]

Coyotes, jackals, and wolves

The

African migration

The first record of Canis on the African continent is Canis sp. A from South Turkwel, Kenya, dated 3.58–3.2 million years ago.[40] In 2015, a study of mitochondrial genome sequences and whole genome nuclear sequences of African and Eurasian canids indicated that extant wolf-like canids have colonised Africa from Eurasia at least 5 times throughout the Pliocene and Pleistocene, which is consistent with fossil evidence suggesting that much of the African canid fauna diversity resulted from the immigration of Eurasian ancestors, likely coincident with Plio-Pleistocene climatic oscillations between arid and humid conditions.[41]: S1 In 2017, the fossil remains of a new Canis species, named Canis othmanii, was discovered among remains found at Wadi Sarrat, Tunisia, from deposits that date 700,000 years ago. This canine shows a morphology more closely associated with canids from Eurasia instead of Africa.[42]

Gallery

-

Gray wolf(Canis lupus)

-

Eastern wolf (Canis lycaon) (includes latrans admixture)

-

Red wolf (Canis rufus) (includes latrans admixture)

-

Coyote (Canis latrans)

-

African wolf (Canis lupaster)

-

Golden jackal (Canis aureus)

-

Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis)

-

Himalayan wolf (Canis lupus chanco)

-

Indian wolf (Canis lupus pallipes)

-

Domestic dog(Canis familiaris)

See also

References

- ^ OCLC 502410693.

- ^ a b Linnæus, Carl (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (in Latin) (10th ed.). Holmiæ (Stockholm): Laurentius Salvius. p. 38. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

- ISBN 1-886106-81-9.

- S2CID 5547543.

- ^ "Opinions and Declarations Rendered by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature - Opinion 91". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 73 (4). 1926.

- ^ Francis Hemming, ed. (1955). "Direction 22". Opinions and Declarations Rendered by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. Vol. 1C. Order of the International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature. p. 183.

- S2CID 83594819.

- PMID 16341006.

- PMID 26234211.

- doi:10.1139/z00-158.

- ^ Alvares, Francisco; Bogdanowicz, Wieslaw; Campbell, Liz A.D.; Godinho, Rachel; Hatlauf, Jennifer; Jhala, Yadvendradev V.; Kitchener, Andrew C.; Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Krofel, Miha; Moehlman, Patricia D.; Senn, Helen; Sillero-Zubiri, Claudio; Viranta, Suvi; Werhahn, Geraldine (2019). "Old World Canis spp. with taxonomic ambiguity: Workshop conclusions and recommendations. CIBIO. Vairão, Portugal, 28th – 30th May 2019" (PDF). IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- S2CID 86755875.

- ^ Fossilworks website Eucyon davisi

- ^ S2CID 231604957.

- ^ Rook, L. 1994. The Plio-Pleistocene Old World Canis (Xenocyon) ex gr. falconeri. Bolletino della Società Paleontologica Italiana 33:71–82.

- .

- PMID 17479753.

- ^ .

- ^ Cherin, Marco; Bertè, Davide Federico; Sardella, Raffaele; Rook, Lorenzo (2013). "Canis etruscus (Canidae, Mammalia) and its role in the faunal assemblage from Pantalla (Perugia, central Italy): comparison with the Late Villafranchian large carnivore guild of Italy". Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana. 52 (1): 11–18.

- PMID 15817436.

- S2CID 86156959.

- .

- S2CID 85236511.

- ISBN 978-0-8018-7416-1.

- ISBN 978-1-4102-0249-9. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- S2CID 83702167.

- ^ PMID 29491991.

- ^ PMID 24905360.

- .

- PMID 28280555.

- S2CID 32107025.

- ^ S2CID 39657617.

- .

- ^ S2CID 222330098.

- ^ DeSantis, L.R.G.; Schubert, B.W.; Schmitt-Linville, E.; Ungar, P.; Donohue, S.; Haupt, R.J. (September 15, 2015). John M. Harris (ed.). "Dental microwear textures of carnivorans from the La Brea Tar Pits, California and potential extinction implications" (PDF). Science Series 42. Contributions in Science (A special volume entitled La Brea and Beyond: the Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County's excavations at Rancho La Brea). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County: 37–52. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2016. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - S2CID 14039133. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2016-12-28. Retrieved 2017-07-13.

- ^ "Wolf - Red, Eastern & Ethiopian Wolves, Extinct Falkland Islands & Dire Wolves | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

- ^ Tokar, E. 2001. "Canis latrans" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed February 24, 2024 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Canis_latrans/

- ^ Parks, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4 0 International Thai National. "Canis aureus, Golden jackal". Thai National Parks. Retrieved 2024-02-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - .

- PMID 26234211.

- .