Cardiovascular disease

| Cardiovascular disease | |

|---|---|

| Medication | Aspirin, beta blockers, blood thinners |

| Deaths | 17.9 million / 32% (2015)[5] |

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is any disease involving the

The underlying mechanisms vary depending on the disease.

It is estimated that up to 90% of CVD may be preventable.

Cardiovascular diseases are the

Types

There are many cardiovascular diseases involving the blood vessels. They are known as vascular diseases.[citation needed]

- Coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease or ischemic heart disease)

- Peripheral arterial disease- a disease of blood vessels that supply blood to the arms and legs

- Cerebrovascular disease - a disease of blood vessels that supply blood to the brain (includes stroke)

- Renal artery stenosis

- Aortic aneurysm

There are also many cardiovascular diseases that involve the heart.

- Cardiomyopathy – diseases of cardiac muscle

- Hypertensive heart disease – diseases of the heart secondary to high blood pressure or hypertension

- Heart failure - a clinical syndrome caused by the inability of the heart to supply sufficient blood to the tissues to meet their metabolic requirements

- Pulmonary heart disease – a failure at the right side of the heart with respiratory system involvement

- Cardiac dysrhythmias– abnormalities of heart rhythm

- Inflammatory heart diseases

- Endocarditis – inflammation of the inner layer of the heart, the endocardium. The structures most commonly involved are the heart valves.

- Inflammatory cardiomegaly

- white blood cells.

- eosinophilicwhite blood cells. This disorder differs from myocarditis in its causes and treatments.

- Valvular heart disease

- Congenital heart disease– heart structure malformations existing at birth

- Rheumatic heart disease – heart muscles and valves damage due to rheumatic fever caused by Streptococcus pyogenes a group A streptococcal infection.

Risk factors

There are many risk factors for heart diseases: age, sex, tobacco use, physical inactivity,

Genetics

Cardiovascular disease in a person's parents increases their risk by ~3 fold,[25] and genetics is an important risk factor for cardiovascular diseases. Genetic cardiovascular disease can occur either as a consequence of single variant (Mendelian) or polygenic influences.[26] There are more than 40 inherited cardiovascular disease that can be traced to a single disease-causing DNA variant, although these conditions are rare.[26] Most common cardiovascular diseases are non-Mendelian and are thought to be due to hundreds or thousands of genetic variants (known as single nucleotide polymorphisms), each associated with a small effect.[27][28]

Age

Age is the most important risk factor in developing cardiovascular or heart diseases, with approximately a tripling of risk with each decade of life.[29] Coronary fatty streaks can begin to form in adolescence.[30] It is estimated that 82 percent of people who die of coronary heart disease are 65 and older.[31] Simultaneously, the risk of stroke doubles every decade after age 55.[32]

Multiple explanations are proposed to explain why age increases the risk of cardiovascular/heart diseases. One of them relates to serum cholesterol level.[33] In most populations, the serum total cholesterol level increases as age increases. In men, this increase levels off around age 45 to 50 years. In women, the increase continues sharply until age 60 to 65 years.[33]

Aging is also associated with changes in the mechanical and structural properties of the vascular wall, which leads to the loss of arterial elasticity and reduced arterial compliance and may subsequently lead to coronary artery disease.[34]

Sex

Men are at greater risk of heart disease than pre-menopausal women.[29][35] Once past menopause, it has been argued that a woman's risk is similar to a man's[35] although more recent data from the WHO and UN disputes this.[29] If a female has diabetes, she is more likely to develop heart disease than a male with diabetes.[36] Women who have high blood pressure and had complications in their pregnancy have three times the risk of developing cardiovascular disease compared to women with normal blood pressure who had no complications in pregnancy.[37][38]

Coronary heart diseases are 2 to 5 times more common among middle-aged men than women.

Among men and women, there are differences in body weight, height, body fat distribution, heart rate, stroke volume, and arterial compliance.[34] In the very elderly, age-related large artery pulsatility and stiffness are more pronounced among women than men.[34] This may be caused by the women's smaller body size and arterial dimensions which are independent of menopause.[34]

Tobacco

Cigarettes are the major form of smoked tobacco.[3] Risks to health from tobacco use result not only from direct consumption of tobacco, but also from exposure to second-hand smoke.[3] Approximately 10% of cardiovascular disease is attributed to smoking;[3] however, people who quit smoking by age 30 have almost as low a risk of death as never smokers.[40]

Physical inactivity

Insufficient physical activity (defined as less than 5 x 30 minutes of moderate activity per week, or less than 3 x 20 minutes of vigorous activity per week) is currently the fourth leading risk factor for mortality worldwide.[3] In 2008, 31.3% of adults aged 15 or older (28.2% men and 34.4% women) were insufficiently physically active.[3] The risk of ischemic heart disease and diabetes mellitus is reduced by almost a third in adults who participate in 150 minutes of moderate physical activity each week (or equivalent).[41] In addition, physical activity assists weight loss and improves blood glucose control, blood pressure, lipid profile and insulin sensitivity. These effects may, at least in part, explain its cardiovascular benefits.[3]

Diet

High dietary intakes of saturated fat, trans-fats and salt, and low intake of fruits, vegetables and fish are linked to cardiovascular risk, although whether all these associations indicate causes is disputed. The World Health Organization attributes approximately 1.7 million deaths worldwide to low fruit and vegetable consumption.

Alcohol

The relationship between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular disease is complex, and may depend on the amount of alcohol consumed.[48] There is a direct relationship between high levels of drinking alcohol and cardiovascular disease.[3] Drinking at low levels without episodes of heavy drinking may be associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease,[49] but there is evidence that associations between moderate alcohol consumption and protection from stroke are non-causal.[50] At the population level, the health risks of drinking alcohol exceed any potential benefits.[3][51]

Celiac disease

Untreated

Sleep

A lack of good sleep, in amount or quality, is documented as increasing cardiovascular risk in both adults and teens. Recommendations suggest that Infants typically need 12 or more hours of sleep per day, adolescent at least eight or nine hours, and adults seven or eight. About one-third of adult Americans get less than the recommended seven hours of sleep per night, and in a study of teenagers, just 2.2 percent of those studied got enough sleep, many of whom did not get good quality sleep. Studies have shown that short sleepers getting less than seven hours sleep per night have a 10 percent to 30 percent higher risk of cardiovascular disease.[7][52]

Sleep disorders such as sleep-disordered breathing and insomnia, are also associated with a higher cardiometabolic risk.[53] An estimated 50 to 70 million Americans have insomnia,

In addition, sleep research displays differences in race and class. Short sleep and poor sleep tend to be more frequently reported in ethnic minorities than in whites. African-Americans report experiencing short durations of sleep five times more often than whites, possibly as a result of social and environmental factors. Black children and children living in disadvantaged neighborhoods have much higher rates of sleep apnea.[8]

Socioeconomic disadvantage

Cardiovascular disease has a greater impact on low- and middle-income countries compared to those with higher income.[54] Although data on the social patterns of cardiovascular disease in low- and middle-income countries is limited[54], reports from high-income countries consistently demonstrate that low educational status or income are associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease.[55] Policies that have resulted in increased socio-economic inequalities have been associated with greater subsequent socio-economic differences in cardiovascular disease[54] implying a cause and effect relationship. Psychosocial factors, environmental exposures, health behaviours, and health-care access and quality contribute to socio-economic differentials in cardiovascular disease.[56] The Commission on Social Determinants of Health recommended that more equal distributions of power, wealth, education, housing, environmental factors, nutrition, and health care were needed to address inequalities in cardiovascular disease and non-communicable diseases.[57]

Air pollution

Cardiovascular risk assessment

Existing cardiovascular disease or a previous cardiovascular event, such as a heart attack or stroke, is the strongest predictor of a future cardiovascular event.

Depression and traumatic stress

There is evidence that mental health problems, in particular depression and traumatic stress, is linked to cardiovascular diseases. Whereas mental health problems are known to be associated with risk factors for cardiovascular diseases such as smoking, poor diet, and a sedentary lifestyle, these factors alone do not explain the increased risk of cardiovascular diseases seen in depression, stress, and anxiety.

Occupational exposure

Little is known about the relationship between work and cardiovascular disease, but links have been established between certain toxins, extreme heat and cold, exposure to tobacco smoke, and mental health concerns such as stress and depression.[68]

Non-chemical risk factors

A 2015 SBU-report looking at non-chemical factors found an association for those:[69]

- with mentally stressful work with a lack of control over their working situation — with an effort-reward imbalance[69]

- who experience low social support at work; who experience injustice or experience insufficient opportunities for personal development; or those who experience job insecurity[69]

- those who work night schedules; or have long working weeks[69]

- those who are exposed to noise[69]

Specifically the risk of

Chemical risk factors

A 2017 SBU report found evidence that workplace exposure to

Workplace exposure to silica dust or asbestos is also associated with pulmonary heart disease. There is evidence that workplace exposure to lead, carbon disulphide, phenoxyacids containing TCDD, as well as working in an environment where aluminum is being electrolytically produced, is associated with stroke.[70]

Somatic mutations

As of 2017, evidence suggests that certain leukemia-associated mutations in blood cells may also lead to increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Several large-scale research projects looking at human genetic data have found a robust link between the presence of these mutations, a condition known as clonal hematopoiesis, and cardiovascular disease-related incidents and mortality.[71]

Radiation therapy

Radiation treatments (RT) for cancer can increase the risk of heart disease and death, as observed in breast cancer therapy.[72] Therapeutic radiation increases the risk of a subsequent heart attack or stroke by 1.5 to 4 times;[73] the increase depends on the dose strength, volume, and location. Use of concomitant chemotherapy, e.g. anthracyclines, is an aggravating risk factor.[74] The occurrence rate of RT induced cardiovascular disease is estimated between 10% and 30%.[74]

Side-effects from radiation therapy for cardiovascular diseases have been termed radiation-induced heart disease or radiation-induced cardiovascular disease.

Pathophysiology

Population-based studies show that atherosclerosis, the major precursor of cardiovascular disease, begins in childhood. The Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth (PDAY) study demonstrated that intimal lesions appear in all the aortas and more than half of the right coronary arteries of youths aged 7–9 years.[78]

Obesity and

Screening

Screening

The NIH recommends lipid testing in children beginning at the age of 2 if there is a family history of heart disease or lipid problems.[91] It is hoped that early testing will improve lifestyle factors in those at risk such as diet and exercise.[92]

Screening and selection for primary prevention interventions has traditionally been done through absolute risk using a variety of scores (ex. Framingham or Reynolds risk scores).[93] This stratification has separated people who receive the lifestyle interventions (generally lower and intermediate risk) from the medication (higher risk). The number and variety of risk scores available for use has multiplied, but their efficacy according to a 2016 review was unclear due to lack of external validation or impact analysis.[94] Risk stratification models often lack sensitivity for population groups and do not account for the large number of negative events among the intermediate and low risk groups.[93] As a result, future preventative screening appears to shift toward applying prevention according to randomized trial results of each intervention rather than large-scale risk assessment.

Prevention

Up to 90% of cardiovascular disease may be preventable if established risk factors are avoided.[9][95] Currently practised measures to prevent cardiovascular disease include:

- Maintaining a healthy diet, such as the Mediterranean diet, a vegetarian, vegan or another plant-based diet.[96][97][98][99]

- Replacing saturated fat with healthier choices: Clinical trials show that replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated vegetable oil reduced CVD by 30%. Prospective observational studies show that in many populations lower intake of saturated fat coupled with higher intake of polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fat is associated with lower rates of CVD.[100]

- Decrease body fat if overweight or obese.[101] The effect of weight loss is often difficult to distinguish from dietary change, and evidence on weight reducing diets is limited.[102] In observational studies of people with severe obesity, weight loss following bariatric surgery is associated with a 46% reduction in cardiovascular risk.[103]

- Limit alcohol consumption to the recommended daily limits.[96] People who moderately consume alcoholic drinks have a 25–30% lower risk of cardiovascular disease.[104][105] However, people who are genetically predisposed to consume less alcohol have lower rates of cardiovascular disease[106] suggesting that alcohol itself may not be protective. Excessive alcohol intake increases the risk of cardiovascular disease[107][105] and consumption of alcohol is associated with increased risk of a cardiovascular event in the day following consumption.[105]

- Decrease non-HDL cholesterol.[108][109] Statin treatment reduces cardiovascular mortality by about 31%.[110]

- Stopping smoking and avoidance of second-hand smoke.[96] Stopping smoking reduces risk by about 35%.[111]

- At least 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) of moderate exercise per week.[112][113]

- Lower blood pressure, if elevated. A 10 mmHg reduction in blood pressure reduces risk by about 20%.[114] Lowering blood pressure appears to be effective even at normal blood pressure ranges.[115][116][117]

- Decrease

- Not enough sleep also raises the risk of high blood pressure. Adults need about 7–9 hours of sleep. Sleep apnea is also a major risk as it causes breathing to stop briefly, which can put stress on the body which can raise the risk of heart disease.[125][126]

Most guidelines recommend combining preventive strategies. There is some evidence that interventions aiming to reduce more than one cardiovascular risk factor may have beneficial effects on blood pressure, body mass index and waist circumference; however, evidence was limited and the authors were unable to draw firm conclusions on the effects on cardiovascular events and mortality.[127]

There is additional evidence to suggest that providing people with a cardiovascular disease risk score may reduce risk factors by a small amount compared to usual care.

Diet

A diet high in fruits and vegetables decreases the risk of cardiovascular disease and death.[131]

A 2021 review found that plant-based diets can provide a risk reduction for CVD if a healthy plant-based diet is consumed. Unhealthy plant-based diets do not provide benefits over diets including meat.[97] A similar meta-analysis and systematic review also looked into dietary patterns and found "that diets lower in animal foods and unhealthy plant foods, and higher in healthy plant foods are beneficial for CVD prevention".[98] A 2018 meta-analysis of observational studies concluded that "In most countries, a vegan diet is associated with a more favourable cardio-metabolic profile compared to an omnivorous diet."[99]

Evidence suggests that the

The DASH diet (high in nuts, fish, fruits and vegetables, and low in sweets, red meat and fat) has been shown to reduce blood pressure,[134] lower total and low density lipoprotein cholesterol[135] and improve metabolic syndrome;[136] but the long-term benefits have been questioned.[137] A high-fiber diet is associated with lower risks of cardiovascular disease.[138]

Worldwide, dietary guidelines recommend a reduction in

The benefits of recommending a

Intermittent fasting

Overall, the current body of scientific evidence is uncertain on whether intermittent fasting could prevent cardiovascular disease.[155] Intermittent fasting may help people lose more weight than regular eating patterns, but was not different from energy restriction diets.[155]

Medication

Blood pressure medication reduces cardiovascular disease in people at risk,[114] irrespective of age,[156] the baseline level of cardiovascular risk,[157] or baseline blood pressure.[158] The commonly-used drug regimens have similar efficacy in reducing the risk of all major cardiovascular events, although there may be differences between drugs in their ability to prevent specific outcomes.[159] Larger reductions in blood pressure produce larger reductions in risk,[159] and most people with high blood pressure require more than one drug to achieve adequate reduction in blood pressure.[160] Adherence to medications is often poor, and while mobile phone text messaging has been tried to improve adherence, there is insufficient evidence that it alters secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.[161]

Aspirin has been found to be of only modest benefit in those at low risk of heart disease, as the risk of serious bleeding is almost equal to the protection against cardiovascular problems.[170] In those at very low risk, including those over the age of 70, it is not recommended.[171][172] The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends against use of aspirin for prevention in women less than 55 and men less than 45 years old; however, it is recommended for some older people.[173]

The use of

Antibiotics for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease

Antibiotics may help patients with coronary disease to reduce the risk of heart attacks and strokes.[175] However, evidence in 2021 suggests that antibiotics for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease are harmful, with increased mortality and occurrence of stroke;[175] the use of antibiotics is not supported for preventing secondary coronary heart disease.

Physical activity

Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation following a heart attack reduces the risk of death from cardiovascular disease and leads to less hospitalizations.[176] There have been few high-quality studies of the benefits of exercise training in people with increased cardiovascular risk but no history of cardiovascular disease.[177]

A systematic review estimated that inactivity is responsible for 6% of the burden of disease from coronary heart disease worldwide.[178] The authors estimated that 121,000 deaths from coronary heart disease could have been averted in Europe in 2008 if people had not been physically inactive. Low-quality evidence from a limited number of studies suggest that yoga has beneficial effects on blood pressure and cholesterol.[179] Tentative evidence suggests that home-based exercise programs may be more efficient at improving exercise adherence.[180]

Dietary supplements

While a

Management

Cardiovascular disease is treatable with initial treatment primarily focused on diet and lifestyle interventions.

Proper CVD management necessitates a focus on MI and stroke cases due to their combined high mortality rate, keeping in mind the cost-effectiveness of any intervention, especially in developing countries with low or middle-income levels.

There are also surgical or procedural interventions that can save someone's life or prolong it. For heart valve problems, a person could have surgery to replace the valve. For arrhythmias, a

There is probably no additional benefit in terms of mortality and serious adverse events when blood pressure targets were lowered to ≤ 135/85 mmHg from ≤ 140 to 160/90 to 100 mmHg.[195]

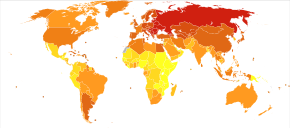

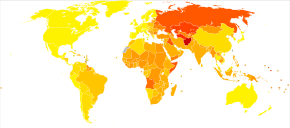

Epidemiology

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death worldwide and in all regions except Africa.[3] In 2008, 30% of all global death was attributed to cardiovascular diseases. Death caused by cardiovascular diseases are also higher in low- and middle-income countries as over 80% of all global deaths caused by cardiovascular diseases occurred in those countries. It is also estimated that by 2030, over 23 million people will die from cardiovascular diseases each year.

It is estimated that 60% of the world's cardiovascular disease burden will occur in the South Asian subcontinent despite only accounting for 20% of the world's population. This may be secondary to a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental factors. Organizations such as the Indian Heart Association are working with the World Heart Federation to raise awareness about this issue.[196]

Research

There is evidence that cardiovascular disease existed in pre-history,

Recent areas of research include the link between inflammation and atherosclerosis[199] the potential for novel therapeutic interventions,[200] and the genetics of coronary heart disease.[201]

References

- ^ "Heart disease". Mayo Clinic. 2022-08-25.

- ^ PMID 23239837.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-4-156437-3. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2014-08-17.

- ^ PMID 25530442.

- ^ PMID 27733281.

- PMID 34959857.

- ^ PMID 25785893.

- ^ PMID 27768852.

- ^ PMID 18316498.

- S2CID 39752176.

- PMID 34881426.

- PMID 24339983.

- PMID 24074752.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-309-14774-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-08.

- PMID 24573352.

- ^ a b "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-11-11.

- ISBN 978-0-309-14774-3.

- S2CID 36437057.

- ^ PMID 23001745.

- ^ PMID 28932354.

- S2CID 248155592.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 30811593.

- ISBN 978-0-07-176372-1.

- PMID 9386201.

- PMID 22424232.

- ^ S2CID 235073575.

- PMID 26343387– via University of Dundee.

- PMID 27324359.

- ^ PMID 23218570.

- PMID 25663838.

- ^ "Understand Your Risk of Heart Attack". American Heart Association.http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartAttack/UnderstandYourRiskofHeartAttack/Understand-Your-Risk-of-Heart-Attack_UCM_002040_Article.jsp

- ISBN 978-92-4-156276-8.

- ^ PMID 10069784.

- ^ PMID 16754702.

- ^ a b "Cardiovascular disease risk factors". World Heart Federation. 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-05-10.

- ^ "Diabetes raises women's risk of heart disease more than for men". NPR.org. May 22, 2014. Archived from the original on May 23, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- S2CID 265356623.

- PMID 37170819.

- ^ Jackson R, Chambles L, Higgins M, Kuulasmaa K, Wijnberg L, Williams D (WHO MONICA Project, and ARIC Study.) Sex difference in ischaemic heart disease mortality and risk factors in 46 communities: an ecologic analysis. Cardiovasc Risk Factors. 1999; 7:43–54.

- PMID 15213107.

- ISBN 978-92-4-154726-0. Archivedfrom the original on 27 April 2016.

- PMID 32827219.

- PMID 18468872.

- PMID 20338284.

- ^ a b "WHO plan to eliminate industrially-produced trans-fatty acids from global food supply" (Press release). World Health Organization. 14 May 2018.

- PMID 24808490.

- S2CID 1589727.

- PMID 28331015.

- PMID 20338493.

- PMID 30955975.

- ISBN 978-92-4-156415-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-07.

- PMID 29907703. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- PMID 27647451.

- ^ S2CID 41892834.

- S2CID 8747779.

- S2CID 21835944.

- ISBN 978-92-4-156370-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-01.

- ^ PMID 22113148.

- ^ PMID 20585020.

- ^ S2CID 6420111.

- ISBN 978-92-4-154717-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-06.

- PMID 25271417.

- PMID 19364974.

- PMID 25154373.

- PMID 27475981.

- PMID 25911639.

- PMID 24176435.

- ^ "NIOSH Program Portfolio : Cancer, Reproductive, and Cardiovascular Diseases : Program Description". CDC. Archived from the original on 2016-05-15. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU) (2015-08-26). "Occupational Exposures and Cardiovascular Disease". www.sbu.se. Archived from the original on 2017-06-14. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ^ a b c d e Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU). "Occupational health and safety – chemical exposure". www.sbu.se. Archived from the original on 2017-06-06. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- PMID 28088988.

- PMID 18035211.

- PMID 20298931.

- ^ S2CID 73477338. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ^ PMID 28911261.

- PMID 34482706.

- PMID 23603848.

- S2CID 36312234.

- S2CID 23913203.

- ^ NPS Medicinewise (1 March 2011). "NPS Prescribing Practice Review 53: Managing lipids". Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- PMID 17184858.

- PMID 14975468.

- S2CID 54227479.

- PMID 29896632.

- PMID 25223981.

- PMID 22847227.

- S2CID 207538193.

- S2CID 196411135.

- S2CID 26077254.

- PMID 29998297.

- PMID 22084329.

- PMID 22510399.

- ^ )

- PMID 27184143.

- S2CID 37833889.

- ^ a b c "Heart Attack—Prevention". NHS Direct. 28 November 2019.

- ^ PMID 34805312.

- ^ PMID 34836208.

- ^ PMID 30571724.

- ^ Frank M. Sacks, Alice H. Lichtenstein, Jason H.Y. Wu, Lawrence J. Appel, Mark A. Creager, Penny M. Kris-Etherton, Michael Miller, Eric B. Rimm, Lawrence L. Rudel, Jennifer G. Robinson, Neil J. Stone, and Linda V. Van Horn: Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association, 15 Jun 2017, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510Circulation 2017;136:e1–e23, https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510

- S2CID 45241607.

- PMID 33555049.

- PMID 24636546.

- PMID 21343207.

- ^ PMID 26936862.

- PMID 25011450.

- S2CID 23782870.

- S2CID 37741456.

- PMID 16330680.

- PMID 27838722.

- )

- ^ "Chapter 4: Active Adults". health.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-03-13.

- ^ "Physical activity guidelines for adults". NHS Choices. 2018-04-26. Archived from the original on 2017-02-19.

- ^ PMID 26724178.

- ^ "Many more people could benefit from blood pressure-lowering medication". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ "expert reaction to study looking at pharmacological blood pressure lowering for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease across different levels of blood pressure | Science Media Centre". Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- .

- S2CID 45312858.

- S2CID 35497445.

- PMID 24856319.

- PMID 24754972.

- PMID 22777025.

- S2CID 9125890.

- PMID 24745774.

- ^ U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2021, March 24). Heart Disease Prevention. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/howtopreventheartdisease.html.

- ^ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Cardiovascular Disease. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/cardiovascular-disease.

- PMID 26272648.

- PMID 28290160.

- PMID 36194420.

- PMID 34011457.

- PMID 25073782.

- PMID 19378874.

- from the original on 2013-12-20.

- PMID 11136953.

- PMID 11451721.

- PMID 16306540.

- PMID 17324730.

- PMID 27193606.

- PMID 23386268.

- ^ PMID 31728492.

- OCLC 712123395. Archived from the originalon 2014-12-28.

- S2CID 43493760.

- PMID 32827219.

- PMID 26268692.

- ^ S2CID 367602.

- S2CID 52013596.

- PMID 30019869.

- PMID 32114706.

- PMID 29387889.

- PMID 25519688.

- S2CID 43795786. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2013-12-20. Retrieved 2013-08-23.

- S2CID 2248777.

- ^ from the original on 2013-12-21.

- PMID 17449506.

- ^ PMID 33512717.

- PMID 18480116.

- S2CID 19951800.

- S2CID 10374187.

- ^ S2CID 10730075.

- PMID 24243703.

- PMID 28455948.

- ^ PMID 22732744.

- PMID 23440795.

- ^ "Statins in primary cardiovascular prevention?". Prescrire International. 27 (195): 183. July–August 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- PMID 26099117.

- PMID 25038074.

- PMID 27849333.

- S2CID 5064731.

- PMID 19655124.

- PMID 21742097.

- ^ "Final Recommendation Statement Aspirin for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Preventive Medication". March 2009. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- PMID 30894318.

- PMID 19293072.

- ABIM Foundation, American College of Chest Physicians and American Thoracic Society, archivedfrom the original on 3 November 2013, retrieved 6 January 2013

- ^ PMID 33704780.

- PMID 34741536.

- PMID 25120097.

- PMID 22818936.

- PMID 24825181.

- PMID 15674925.

- PMID 28301692.

- PMID 21575619.

- PMID 23335472.

- S2CID 51615818.

- PMID 24217421.

- PMID 20079494.

- PMID 23265337.

- PMID 12160191.

- PMID 16935995.

- PMID 22493407.

- S2CID 254343574.

- S2CID 205176857.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-55593-7.

- ^ "What is Cardiovascular Disease?". www.heart.org. 31 May 2017.

- PMID 36398903.

- ^ Roo S. "Cardiac Disease Among South Asians: A Silent Epidemic". Indian Heart Association. Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2018-12-31.

- S2CID 16928278.

- ISSN 1473-6357.

- PMID 27905474.

- PMID 28094270.

- S2CID 13738641.