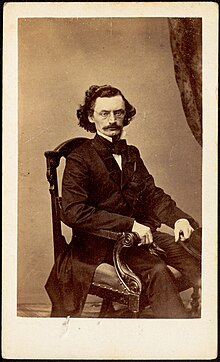

Carl Schurz

Carl Schurz | |

|---|---|

United States Minister to Spain | |

| In office July 13, 1861 – December 18, 1861 | |

| President | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | William Preston |

| Succeeded by | Gustav Körner |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Carl Christian Schurz March 2, 1829 German revolutions of 1848–49 (1861–1865)American Civil War |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Liberalism in the United States |

|---|

|

Carl Schurz (German:

Born in the

After the war, Schurz established a newspaper in

After Republican

Early life

Carl Christian Schurz was born on March 2, 1829, in Liblar (now part of

Revolution of 1848

At Bonn, he developed a friendship with one of his professors,

These roles were reversed when Kinkel left for Berlin to become a member of the Prussian Constitutional Convention.

During the 1849 military campaign in Palatinate and Baden, he joined the revolutionary army, fighting in several battles against the Prussian Army.

When the revolutionary army was defeated at the

Migration to America

While in London, Schurz married fellow revolutionary

In Wisconsin, Schurz soon became immersed in the anti-slavery movement and in politics, joining the

After Lincoln's election and in spite of Seward's objection, Lincoln sent Schurz as minister to Spain in 1861,[13] in part because of Schurz's European record as a revolutionary.[10] While there, Schurz did not manage to cause any lasting impact on the Spanish authorities regarding the conflict.[14] He returned to the US in early 1862 to join the Union army.

American Civil War

During the

Following Gettysburg, Schurz's division was deployed to Tennessee and participated in the

In the summer of 1865, President Andrew Johnson sent Schurz through the South to study conditions. They then quarreled because Schurz supported General Slocum's order forbidding the organization of militia in Mississippi. Schurz delivered a report to the U.S. Senate documenting conditions in the South which concluded that Reconstruction had succeeded in restoring the basic functioning of government but failed in restoring the loyalty of the people and protecting the rights of the newly legally emancipated who were still considered the slaves of society.[15] It called for a national commitment to maintaining control over the South until free labor was secure, arguing that without national action, Black Codes and violence including numerous extrajudicial killings documented by Schurz were likely to continue.[15] The report was ignored by the President, but it helped fuel the movement pushing for a larger congressional role in Reconstruction and holding Southern states to higher standards.[16][10]

Newspaper career

In 1866, Schurz moved to Detroit, where he was chief editor of the Detroit Post. The following year, he moved to St. Louis, becoming editor and joint proprietor with Emil Preetorius of the German-language Westliche Post (Western Post), where he hired Joseph Pulitzer as a cub reporter. In the winter of 1867–1868, he traveled in Germany; his account of his interview with Otto von Bismarck is one of the most interesting chapters of his Reminiscences. He spoke against "repudiation" of war debts and for "honest money"—code for going back on the gold standard—during the presidential campaign of 1868.[10]

U.S. Senator

In 1868, he was elected to the

After William P. Fessenden's death, Schurz became a member of the Committee on Foreign Affairs where Schurz opposed Grant's Southern policy as well as his bid to annex Santo Domingo. Schurz was identified with the committee's investigation of arms sales to and cartridge manufacture for the French army by the United States government during the Franco-Prussian War.

In 1869, he became the first U.S. Senator to offer a

In 1870, Schurz helped form the Liberal Republican Party, which opposed President Ulysses S. Grant's annexation of Santo Domingo and his use of the military to destroy the Ku Klux Klan in the South under the Enforcement Acts.

In 1872, he presided over the Liberal Republican Party convention, which nominated

Schurz lost the 1874 Senatorial election to

Secretary of the Interior

In 1876, he supported Hayes for President, and Hayes named him

During Schurz's tenure as Secretary of the Interior, a movement to transfer the Office of Indian Affairs to the control of the War Department began, assisted by the strong support of Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman.[21] Restoration of the Indian Office to the War Department, which was anxious to regain control in order to continue its "pacification" program, was opposed by Schurz, and ultimately the Indian Office remained in the Interior Department. The Indian Office had been the most corrupt office in the Interior Department. Positions in it were based on political patronage and were seen as granting license to use the reservations for personal enrichment. Because Schurz realized that the service would have to be cleansed of such corruption before anything positive could be accomplished, he instituted a wide-scale inspection of the service, dismissed several officials, and began civil service reforms whereby positions and promotions were to be based on merit not political patronage.[22]

Schurz's leadership of the Indian Affairs Office was at times controversial. While certainly not an architect of forced displacement of Native Americans, he continued the practice. In response to several nineteenth-century reformers, however, he later changed his mind and promoted an assimilationist policy.[23][24]

Later life

Upon leaving the Interior Department in 1881, Schurz moved to

In 1884, he was a leader in the Independent (or

True to his anti-imperialist convictions, Schurz exhorted McKinley to resist the urge to annex land following the

Death and legacy

Schurz died at age 77 on May 14, 1906, in New York City, and is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Sleepy Hollow, New York.[31]

Schurz's wife, Margarethe Schurz, was instrumental in establishing the kindergarten system in the United States.[32]

Schurz is famous for saying: "My country, right or wrong; if right, to be kept right; and if wrong, to be set right."[33]

He was portrayed by Edward G. Robinson as a friend of the surviving Cheyenne Indians in John Ford's 1964 film Cheyenne Autumn.

Works

Schurz published a volume of speeches (1865), a two-volume biography of Henry Clay (1887), essays on Abraham Lincoln (1899) and Charles Sumner (posthumous, 1951), and his Reminiscences (posthumous, 1907–09). His later years were spent writing the memoirs recorded in his Reminiscences which he was not able to finish, reaching only the beginnings of his U.S. Senate career. Schurz was a member of the Literary Society of Washington from 1879 to 1880.[34]

Memorials

Schurz is commemorated in numerous places around the United States:

- Mayor of New Yorksince 1942

- Morningside Park, at Morningside Drive and 116th Street in New York City

- Karl Bitter's 1914 monument to Schurz ("Our Greatest German American") in Menominee Park, Oshkosh, Wisconsin[35]

- Carl Schurz and Abraham Jacobi Memorial Park in Bolton Landing, New York

- Schurz, Nevada named after him[36]

- Carl Schurz Drive, a residential street in the northern end of his former home of Watertown, Wisconsin

- Schurz Elementary School, in Watertown, Wisconsin

- Carl Schurz Park, a private membership park in Stone Bank (Town of Merton), Wisconsin, on the shore of Moose Lake

- Carl Schurz Forest, a forested section of the Monches, Wisconsin

- Carl Schurz High School, a historic landmark in Chicago, built in 1910.

- Schurz Hall, a student residence at the University of Missouri.

- Carl Schurz Elementary School in New Braunfels, Texas

- Mount Schurz, a mountain in eastern Yellowstone, north of Eagle Peak and south of Atkins Peak, named in 1885 by the United States Geological Survey, to honor Schurz's commitment to protecting Yellowstone National Park

- In 1983, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 4-cent Great Americans series postage stamp with his name and portrait

- In World War II, the United States liberty ship SS Carl Schurz was named in his honor.

- The German Imperial Navy, the ship had been taken over by the U.S. Navy when hostilities between Germany and the U.S. commenced, after having been interned in Honolulu in 1914. The Schurz sank after a collision on 21 June 1918 off Beaufort Inlet, North Carolina.

Several memorials in Germany also commemorate the life and work of Schurz, including:

- Carl-Schurz Kaserne, in Bremerhaven, has been home to U.S. Army units for several decades, including elements of the 2nd Armored Division (Forward). Today it houses Army transportation units and some civilian commercial activities related to commercial shipping.

- Streets named after him in Berlin-Spandau, Bremen, Stuttgart, Erftstadt-Liblar, Giessen, Heidelberg, Karlsruhe, Cologne, Neuss, Rastatt, Paderborn, Pforzheim, Pirmasens, Leipzig, Wuppertal, and Bad Kreuznach

- Schools in Frankfurt am Main, Rastatt and his place of birth, Erftstadt-Liblar

- The Carl-Schurz-Haus Freiburg, in Freiburg im Breisgau is an innovative institute (formerly Amerika-Haus) fostering German-American cultural relations

- an urban area in Frankfurt am Main

- the Carl Schurz Bridge over the Neckar River[37]

- a memorial fountain as well as the house where Lt. Schurz was billeted in 1849 in Rastatt

- German Armed Forces barracks in Hardheim

- German federal stamps in 1952 and 1976

- Carl-Schurz-Medal awarded annually to one distinguished citizen of his home town.

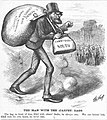

Harper's Weekly gallery

-

Schurz and other anti-Grant "conspirators" – March 16, 1872

-

French Arms investigation – May 11, 1872

-

Schurz and his victims – September 7, 1872

-

Schurz is depicted as a carpetbagger - November 9, 1872.

-

Schurz leaves the U.S. Senate – March 20, 1875

-

Schurz reforms the Indian Bureau – January 26, 1878

-

Schurz counsels a wounded settler – December 28, 1878

-

Schurz and Wilhelm II – July 14, 1900

-

Schurz and Emilio Aguinaldo – August 9, 1902

-

- February 26, 1881

See also

- List of foreign-born United States Cabinet members

- List of American Civil War generals (Union)

- Forty-Eighters

- German Americans in the Civil War

- German American

- German-American Heritage Foundation of the USA

- List of United States senators born outside the United States

Letter from Carl Schurz to Abraham Lincoln, November 8, 1862.

Letter from Carl Schurz to Abraham Lincoln, November 8, 1862.

Notes

- ISBN 3-8253-1256-9.

- ^ "Schurz, Carl (1829-1906)". Wisconsin Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2013-10-30. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2021-05-12.

- ISBN 0253108411. Retrieved 2 November 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Dictionary Of American Biography (1935), Carl Schurz, p. 466.

- ^ Schurz, Carl. Reminiscences, Vol. 1, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Van Cleve, Charles L. (1902). Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity From Its Foundation In 1852 To Its Fiftieth Anniversary. p. 209: Philadelphia: Franklin Printing Company.

- ^ Schurz, Reminiscences, Vol. 1, Chap. 6, pp. 159.

- ^ W. R. Mc Cormick: BAY COUNTY Memorial Report: Emil Anneke: in: Report of the Pioneer Society of the State of Michigan, Vol. XIV, 1890, Lansing, Michigan, W. S. George & Co., State Printers & Binders, Page 57–58 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chisholm 1911, p. 390.

- ^ Killian, Marcella (April 28, 1952). "Carl Schurz". Watertown Historical Society.

- ^ Hirschhorn, p. 1713.

- ^ Dictionary Of American Biography (1935), Carl Schurz, p. 467

- ISBN 978-0-8262-1938-1.

- ^ a b Schurz, Carl. "Report on the Condition of the South". gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- ^ "Report on the Condition of the South". Teaching American History. Retrieved 2022-05-04.

- ^ Mejías-López (2009), The Inverted Conquest, p. 132.

- ^ Brands (2012), The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses S. Grant in War and Peace, p. 489.

- ^ This story, and the conflict between Nast and Harper's editorial writer George William Curtis, is related by Albert Bigelow Paine in Thomas Nast: His Period and His Pictures, 1904.

- ^ a b c Fishel-Spragens (1988), Popular Images of American Presidents, p. 121

- ^ "Army charges answered". The New York Times: 5. December 7, 1878.

ARMY CHARGES ANSWERED; THE INDIAN SERVICE UPHELD BY MR. SCHURZ. WHY IT WOULD BE UNWISE TO TRANSFER THE INDIAN BUREAU TO THE WAR DEPARTMENT--INCONSISTENT AND INACCURATE STATEMENTS BY MILITARY OFFICERS--LOOSE MANAGEMENT UNDER THE ARMY. INCONSISTENT AND INACCURATE STATEMENTS BY ARMY OFFICERS. ALLEGED ARMY DISHONESTY. MEASURES OF IMPORTANCE. MR. SCHURZ CROSS-EXAMINED. OTHER WITNESSES

- ^ Trefousse, Hans L., Carl Schurz: A Biography, (U. of Tenn. Press, 1982)

- ^ Hoxie, Frederick E. A Final Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880-1920, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1981.

- ^ "Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior, November 1, 1880," In Prucha, Francis Paul, ed., Documents of United States Indian Policy, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2000. See Google Books.

- ^ Sturm und Drang Over a Memorial to Heinrich Heine. The New York Times, May 27, 2007.

- ^ Villard, Oswald Garrison (1936). "White, Horace". Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- ^ "No Longer an Editor; Carl Schurz Severs his Connection with the 'Evening Post'." The New York Times, December 11, 1883

- ^ Chisholm 1911, pp. 390–391.

- ^ Tucker (1998), p. 114.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 391.

- ^ German Monuments in the Americas

- ^ "Schurz, Margarethe [Meyer] (Mrs. Carl Schurz) 1833 - 1876". Wisconsin Historical Society. 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ Schurz, Carl, remarks in the Senate, February 29, 1872, The Congressional Globe, vol. 45, p. 1287. See Wikisource for the complete speech.

- ^ Spauling, Thomas M. (1947). The Literary Society in Peace and War. Washington, D.C.: George Banta Publishing Company.

- ^ "Schurz Monument - Postcard - Wisconsin Historical Society". December 2003. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1941). Origin of Place Names: Nevada (PDF). W.P.A. p. 53.

- ^ "Schurz Bridge". Retrieved 2 November 2016.

References

- Eicher, John H., and ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Schurz, Carl". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 390–391.

- Tucker, David M. (1998). Mugwumps: public moralists of the gilded age. ISBN 0-8262-1187-9.

- ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

Further reading

- Schurz, Carl. The Reminiscences of Carl Schurz (three volumes), New York: McClure Publ. Co., 1907–08. Schurz covered the years 1829–1870 in his Reminiscences. He died in the midst of writing them. The third volume is rounded out with A Sketch of Carl Schurz's Political Career 1869–1906 by Frederic Bancroft and William A. Dunning. Portions of these Reminiscences were serialized in McClure's Magazine about the time the books were published and included illustrations not found in the books.

- Bancroft, Frederic, ed. Speeches, Correspondence, and Political Papers of Carl Schurz (six volumes), New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1913.

- Brown, Dee, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, 1971

- Donner, Barbara. "Carl Schurz as Office Seeker," Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 20, no.2 (December 1936), pp. 127–142.

- Donner, Barbara. "Carl Schurz the Diplomat," Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 20, no. 3 (March 1937), pp. 291–309.

- Fish, Carl Russell. "Carl Schurz-The American," Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 12, no. 4 (June 1929), pp. 346–368.

- Fuess, Claude Moore Carl Schurz, Reformer, (NY, Dodd Mead, 1932)

- Nagel, Daniel. Von republikanischen Deutschen zu deutsch-amerikanischen Republikanern. Ein Beitrag zum Identitätswandel der deutschen Achtundvierziger in den Vereinigten Staaten 1850–1861. Röhrig, St. Ingbert 2012.

- Schafer, Joseph. "Carl Schurz, Immigrant Statesman," Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 11, no. 4 (June 1928), pp. 373–394.

- Schurz, Carl. Intimate Letters of Carl Schurz 1841-1869, Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1928.

- Trefousse, Hans L. Carl Schurz: A Biography, (1st ed. Knoxville: U. of Tenn. Press, 1982; 2nd ed. New York: Fordham University Press, 1998)

- Twain, Mark, "Carl Schurz, Pilot," Harper's Weekly, May 26, 1906.

External links

Media related to Carl Schurz at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Carl Schurz at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Carl Schurz at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Carl Schurz at Wikiquote Works by or about Carl Schurz at Wikisource

Works by or about Carl Schurz at Wikisource German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Carl Schurz

German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Carl Schurz

- United States Congress. "Carl Schurz (id: S000151)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2008-08-12

- Works by Carl Schurz at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Carl Schurz at Internet Archive

- Reynolds, Robert L. "A Man of Conscience", American Heritage Magazine, vol. 14, no. 2 (1963).

- "Schurz: The True Americanism" Harper's Magazine, November 1, 2008.

- "Carl Schurz" from Charles Rounds, Wisconsin Authors and Their Works, 1918.

- The Political Graveyard

- Abraham Lincoln's White House - Carl Schurz Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- The Carl Schurz Papers, containing materials especially of interest to the examination of Schurz's image in the press and in the German-American community, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- Constitutional Minutes episode about Carl Schurz from the American Archive of Public Broadcasting

- Newspaper clippings about Carl Schurz in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Constitutional Minutes- Series : Constitutional Minutes; Episode : Carl Schurz; Episode Number: 112 from American Archive of Public Broadcasting