Castel Sant'Angelo

| |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Coordinates | 41°54′11″N 12°27′59″E / 41.9031°N 12.4663°E |

|---|---|

| Type | Mausoleum |

| History | |

| Builder | Hadrian |

| Founded | 123–139 AD |

The Mausoleum of Hadrian, also known as Castel Sant'Angelo (Italian pronunciation: for himself and his family. The popes later used the building as a fortress and castle, and it is now a museum. The structure was once the tallest building in Rome.

Hadrian's tomb

The tomb of the Roman emperor

Decline

Much of the tomb contents and decorations have been lost since the building's conversion to a military

...in order to build churches for the use of the Christians, not only were the most honoured temples of the idols [pagan Roman gods] destroyed, but in order to ennoble and decorate Saint Peter's with more ornaments than it then possessed, they took away the stone columns from the tomb of Hadrian, now the castle of Sant'Angelo, as well as many other things which we now see in ruins.[4]

Legend holds that the

Papal fortress, residence and prison

The popes converted the structure into a castle, beginning in the 14th century;

Montelupo's statue was replaced by a bronze statue of the same subject, executed by the Flemish sculptor Peter Anton von Verschaffelt, in 1753. Verschaffelt's is still in place and Montelupo's can be seen in an open court in the interior of the Castle.[citation needed]

The

During earlier times, the prison had another remarkable function. Cornelis de Bruijn mentioned that when Pope Clement X died in 1796, all prisoners with heavy sentences were transported to St. Angelo. Then, as soon as the papal seat became vacant, the local city council would release all prisoners from Rome's prisons except those that were locked in St. Angelo. This chain of events was, according to Cornelis, a custom every time the pope died.[9]

Fireworks

When visiting the castel in 1776 Cornelis de Bruijn mentioned the fireworks that were apparently on display once a year. He wrote:

"Another fireworks display, remarkable to behold, is the customary yearly celebration on St. Peter's Day at the castle of St. Angelo. It appears as if coming from above the castle, igniting simultaneously and spreading through the crowd of the fireworks in such a way that, when standing near the castle, it feels as though the heavens themselves are opening up. Being about half an hour away from there, one can still observe it quite clearly. Having spent more than a year in Rome, I was curious to observe it from multiple locations, but found the location near the castle, where one stands beneath the fireworks, to be the most delightful.[9]"

Museum

Decommissioned in 1901, the castle is now a museum: the Museo Nazionale di Castel Sant'Angelo. It received 1,234,443 visitors in 2016.[10]

Gallery

-

Model of the Mausoleum of Hadrian

-

View from south towards the Castel Sant'Angelo and Ponte Sant'Angelo

-

The original angel by Raffaello da Montelupo

-

Bronze statue of Michael the Archangel, standing on top of the Castel Sant'Angelo, modelled in 1753 by Peter Anton von Verschaffelt (1710–1793)

-

Another angle of the angel

-

Giovanni Battista Bugatti, papal executioner between 1796 and 1861, offering snuff to a condemned prisoner in front of Castel Sant'Angelo.

-

View of the river Tiber looking south with the Castel Sant'Angelo and Saint Peter's Basilica beyond, Rudolf Wiegmann 1834

See also

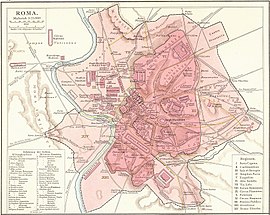

- List of ancient monuments in Rome

- List of tourist attractions in Rome

- Cardinal-nephew

- Concordat of Worms

- List of castles in Italy

- Sistine Chapel ceiling

- Stand of the Swiss Guard

- Via della Conciliazione

Bibliography

- Bruno Contardi; Marica Mercalli; Italy.

References

- ^ Gibbon, Edward (1826). The history of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire. Vol. 6 (4th American ed.). New York. p. 369.

- ^ Aicher, Peter J (2004). Rome Alive: A Source-Guide to the Ancient City Volume I. Bolchazy-Carducci. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "Porphyry Baptismal Font". Archived from the original on 2014-01-12. Retrieved 2014-01-12.

- ^ "Preface, "Lives of the Artists"". Archived from the original on 2010-12-10. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ^ Account of Pedro Tafur in The Travels of Pero Tafur (1435–1439), Chapter III.

- ISBN 978-3822863053.

- ^ Rome (Eyewitness Travel Guides) DK Publishing, London (2003) p. 242

- ^ Mausoleum of Hadrian (Castel San'tAngelo), retrieved 2023-09-03

- ^ a b "Reizen van Cornelis de Bruyn door de vermaardste deelen van Klein Asia". Archived from the original on 2023-07-27. Retrieved 2023-07-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), Amsterdam, 1698. - ^ "Musei, monumenti e aree archeologiche statali" [State museums, monuments and archaeological areas] (PDF). ilsole24ore.it (in Italian). 5 January 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

External links

- Official website

- Site describing arrangement of the original mausoleum.

- Mausoleum of Hadrian, part of the Encyclopædia Romana by James Grout

- Platner and Ashby entry on the tomb on Lacus Curtius site

- Roman Bookshelf – Views of Castel Sant'Angelo from the 19° Century

- Hadrian's tomb Model of how the tomb might have appeared in antiquity

- Castel Sant'Angelo: History Of Torture, Ghosts And Mystery

![]() Media related to Castel Sant'Angelo (Rome) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Castel Sant'Angelo (Rome) at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Casa dei Cavalieri di Rodi |

Landmarks of Rome Castel Sant'Angelo |

Succeeded by Palazzo Aragona Gonzaga |