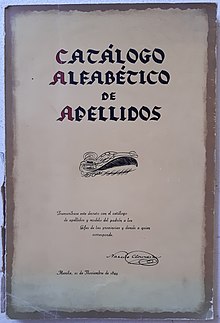

Catálogo alfabético de apellidos

| |

| Author | Narciso Clavería y Zaldúa; Domingo Abella[1] |

|---|---|

| Language | Spanish |

| Published | 1849 (reprinted in 1973)[1][2] |

| Publisher | Manila : National Archives & Records Administration, Central Plains Region[1] |

| Pages | 141 |

The Catálogo alfabético de apellidos (English: Alphabetical Catalogue of Surnames;

The book was created after Spanish governor-general

Dissemination of surnames

According to the decree, a copy of the catalogue, which contains 61,000 surnames,[5] was to be distributed to the provincial heads of the archipelago. From there, a certain number of surnames, based on population, were sent to each barangay's parish priest.[6] The head of each barangay, along with another town official or two, was present when the father or the oldest person in each family chose a surname for his or her family. A surname is given to only one family per municipality to reduce any issues about surnames being associated with an ethnic background or group affiliation.[7] The dissemination of surnames were also based on the recipient family's origins. For example, surnames starting with "A" were distributed to provincial capitals, "B" surnames were given to secondary towns, and tertiary towns received "C" surnames.[8]

Families were awarded with the surnames or asked to choose from them.[9] However, several groups were exempt from having to choose new surnames:

- Those with a previously adopted surname (whether indigenous or foreign) already on the list or, if not on the list, not prohibited because of ethnic origin or being too common.

- Families who had already adopted a prohibited surname but could prove their family had used the name for at least four consecutive generations. (Those were names prohibited for being too common, like de los Santos or de la Cruz or for other reasons.)

Spanish names are the majority found in the books' list of legitimate surnames. Because of the mass implementation of Spanish surnames in the Philippines, a Spanish surname does not necessarily indicate Spanish ancestry, which can make it difficult for Filipinos to accurately trace their lineage.[10]

See also

References

- ^ OCLC 865725433.

- ^ Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society. University of San Carlos. 1992. p. 104. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ISBN 9781483365602. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ISBN 9781851096756. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ Querubin, Pablo (October 2015). "Family and Politics: Dynastic Persistence in the Philippines" (PDF). Retrieved February 13, 2017.[permanent dead link]

- )

- ^ Fafchamps, Marcel; Labonne, Julien (December 2013). "Do Politicians' Relatives Get Better Jobs? Evidence from Municipal Elections in the Philippines" (PDF). Retrieved February 13, 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ISBN 9781137413079. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- .

- S2CID 132890899.

External links

- Catalog of Filipino Surnames by Hector Santos.

- Clavería y Zaldúa, Narciso (1973) [November 21, 1849]. Catálogo alfabético de apellidos (reprint). Philippine National Archives, Manila.