Christian culture

| Part of a series on |

| Christian culture |

|---|

|

| Christianity portal |

Christian culture generally includes all the cultural practices which have developed around the religion of Christianity. There are variations in the application of Christian beliefs in different cultures and traditions.

Christian culture has influenced and assimilated much from the Middle Eastern,[1][2] Zoroastrianism,[3] Greco-Roman, Byzantine, Western culture,[4] Slavic and Caucasian culture. During the early Roman Empire, Christendom has been divided in the pre-existing Greek East and Latin West. Consequently, different versions of the Christian cultures arose with their own rites and practices, Christianity remains culturally diverse in its Western and Eastern branches.

Christianity played a prominent role in the development of Western civilization, in particular, the Catholic Church and Protestantism.[5] Western culture, throughout most of its history, has been nearly equivalent to Christian culture.[6] Outside the Western world, Christianity has had an influence on various cultures, such as in Africa and Asia.[7][8]

Cultural influence

The

Since the spread of Christianity from the

Outside the Western world, Christianity has had an influence on various cultures, such as in Africa, the Near East, Middle East, Central Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.

Historian Paul Legutko of Stanford University said the

Influence on Western culture

Although Western culture contained several polytheistic religions during its early years under the

Christianity had a significant impact on education and science and medicine as the church created the basis of the Western system of education,

The cultural influence of Christianity includes

Christianity played a role in ending practices common among pagan societies, such as human sacrifice, slavery,[90] infanticide and polygamy.[91] Scientists such as Newton and Galileo believed that God would be better understood if God's creation was better understood.[92]

Architecture

The architecture of cathedrals, basilicas and abbey churches is characterised by the buildings' large scale and follows one of several branching traditions of form, function and style that all ultimately derive from the

Cathedrals in particular, as well as many

The earliest large churches date from

-

San Francisco de Asís Church

Art

Images of

Christianity makes far wider use of images than related religions, in which figurative representations are forbidden, such as Islam and Judaism. However, there is also a considerable history of aniconism in Christianity from various periods.

Illumination

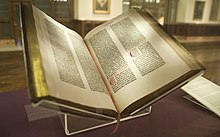

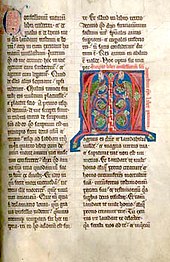

An

Most illuminated manuscripts were created as codices, which had superseded scrolls; some isolated single sheets survive. A very few illuminated manuscript fragments survive on papyrus. Most medieval manuscripts, illuminated or not, were written on parchment (most commonly of calf, sheep, or goat skin), but most manuscripts important enough to illuminate were written on the best quality of parchment, called vellum, traditionally made of unsplit calfskin, although high quality parchment from other skins was also called parchment.

Iconography

Christian art began, about two centuries after Christ, by borrowing motifs from Roman Imperial imagery, classical Greek and Roman religion and popular art.

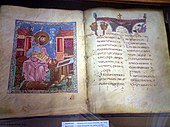

An

Each saint has a story and a reason why he or she led an exemplary life. Symbols have been used to tell these stories throughout the history of the Church. A number of Christian saints are traditionally represented by a symbol or iconic motif associated with their life, termed an attribute or emblem, in order to identify them. The study of these forms part of iconography in Art history.

Eastern Christian art

The dedication of

This achievement was checked by the controversy over the use of graven images, and the proper interpretation of the Second Commandment, which led to the crisis of

The art of

Although the influence has often been resisted, especially in Russia, Catholic art has also affected Orthodox depictions in many respects, especially in countries like Romania, and in the post-Byzantine

Many Eastern Orthodox states in Eastern Europe, as well as to some degree the

Catholic art

The earliest surviving art works are the painted frescoes on the walls of the

Renaissance artists such as Raphael, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Bernini, Botticelli, Fra Angelico, Tintoretto, Caravaggio, and Titian, were among a multitude of innovative virtuosos sponsored by the Church.[97]

British art historian

Later, during

[W]ith a single exception, the great artists of the time were all sincere, conforming Christians.

Rubens attended Mass every morning before beginning work. The exception was Caravaggio, who was like the hero of a modern play, except that he happened to paint very well. This conformism was not based on fear of the Inquisition, but on the perfectly simple belief that the faith which had inspired the great saints of the preceding generation was something by which a man should regulate his life.

-

Adoration of the Shepherds by Gerard van Honthorst, 1622

-

Master of the Holy Kinship, 1500

-

The Transfiguration by Raphael, c. 1520

-

Last Supper, 1498.

Protestant art

The

Prominent painters with Protestant background were, for example,

, and many others.Education

The university is generally regarded as an institution that has its origin in the Medieval Christian setting.[64][63][99] Prior to the establishment of universities, European higher education took place for hundreds of years in Christian cathedral schools or monastic schools (Scholae monasticae), in which monks and nuns taught classes; evidence of these immediate forerunners of the later university at many places dates back to the 6th century AD.[100]

Missionary activity for the Catholic Church has always incorporated education of evangelized peoples as part of its social ministry. History shows that in evangelized lands, the first people to operate schools were Roman Catholics. In some countries, the Church is the main provider of education or significantly supplements government forms of education. Presently, the Church operates the world's largest non-governmental school system.[101][102] Many of Western Civilization's most influential universities were founded by the Catholic Church.

The Catholic Church founded the West's first universities, which were preceded by the schools attached to monasteries and cathedrals, and generally staffed by monks and friars.

As the Reformers wanted all members of the church to be able to read the Bible, education on all levels got a strong boost. Compulsory education for both boys and girls was introduced. For example, the

A large number of

Some of the first colleges and universities in America, including

According to

A

Literature and poetry

Christian literature is writing that deals with Christian themes and incorporates the Christian world view. This constitutes a huge body of extremely varied writing. Christian poetry is any poetry that contains Christian teachings, themes, or references. The influence of Christianity on poetry has been great in any area that Christianity has taken hold. Christian poems often directly reference the Bible, while others provide allegory.

While falling within the strict definition of literature, the Bible is not generally considered literature. However, the Bible has been treated and appreciated as literature; the

In

The list of Catholic authors and literary works is vast. With a literary tradition spanning two millennia, the Bible and

Catholics have also given greater value to the world through literary works by

Medicine and health care

The administration of the Eastern and Western Roman Empires split and the

The

Geoffrey Blainey likened the Catholic Church in its activities during the Middle Ages to an early version of a welfare state: "It conducted hospitals for the old and orphanages for the young; hospices for the sick of all ages; places for the lepers; and hostels or inns where pilgrims could buy a cheap bed and meal". It supplied food to the population during famine and distributed food to the poor. This welfare system the church funded through collecting taxes on a large scale and possessing large farmlands and estates.[134] It was common for monks and clerics to practice medicine and medical students in northern European universities often took minor Holy orders. Mediaeval hospitals had a strongly Christian ethos, and were, in the words of historian of medicine Roy Porter, "religious foundations through and through", and Ecclesiastical regulations were passed to govern medicine, partly to prevent clergymen profiting from medicine.[135] During Europe's Age of Discovery, Catholic missionaries, notably the Jesuits, introduced the modern sciences to India, China and Japan. While persecutions continue to limit the spread of Catholic institutions to some Middle Eastern Muslim nations, and such places as the People's Republic of China and North Korea, elsewhere in Asia the church is a major provider of health care services - especially in Catholic Nations like the Philippines.

Today the

Music

Like other forms of music the creation, performance, significance, and even the definition of Christian music varies according to culture and social context. Christian music is composed and performed for many purposes, ranging from aesthetic pleasure, religious or ceremonial purposes, or as an entertainment product for the marketplace.

In music, Catholic monks developed the first forms of modern Western musical notation in order to standardize liturgy throughout the worldwide Church,[139] and an enormous body of religious music has been composed for it through the ages. This led directly to the emergence and development of European classical music, and its many derivatives. The Baroque style, which encompassed music, art, and architecture, was particularly encouraged by the post-Reformation Catholic Church as such forms offered a means of religious expression that was stirring and emotional, intended to stimulate religious fervor.[140]

The list of Catholic composers and Catholic sacred music which have a prominent place in Western culture is extensive, but includes

.| Josquin des Prez (1450/1455 – 1521) |

Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) |

Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) |

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) |

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) |

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) |

Franz Schubert (1797–1828) |

Franz Liszt (1811–1886) |

Anton Bruckner (1824–1896) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Philosophy

Medieval philosophy is the philosophy of Western Europe and the Middle East during the

learning.The history of western European medieval philosophy is traditionally divided into two main periods: the period in the

The medieval era was disparagingly treated by the Renaissance humanists, who saw it as a barbaric "middle" period between the classical age of Greek and Roman culture, and the "rebirth" or renaissance of classical culture. Yet this period of nearly a thousand years was the longest period of philosophical development in Europe, and possibly the richest.

Some problems discussed throughout this period are the relation of faith to reason, the existence and unity of God, the object of theology and metaphysics, the problems of knowledge, of universals, and of individuation.

Philosophers from the Middle Ages include the Christian philosophers

Aquinas, father of

The Renaissance ("rebirth") was a period of transition between the Middle Ages and modern thought,[143] in which the recovery of classical texts helped shift philosophical interests away from technical studies in logic, metaphysics, and theology towards eclectic inquiries into morality, philology, and mysticism.[144] The study of the classics and the humane arts generally, such as history and literature, enjoyed a scholarly interest hitherto unknown in Christendom, a tendency referred to as humanism.[145] Displacing the medieval interest in metaphysics and logic, the humanists followed Petrarch in making man and his virtues the focus of philosophy.[146]

These new movements in philosophy developed contemporaneously with larger religious and political transformations in Europe: the

| Tertullian (c. 155 – c. 240 AD) |

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215) |

Athanasius of Alexandria (c. 296–298 – 373) |

Augustine of Hippo (354–430) |

Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) |

William of Ockham (c. 1287 – 1347) |

Hugo Grotius (1583–1645) |

Blaise Pascal (1623–1662) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Science and technology

Earlier attempts at reconciliation of Christianity with

Christian philosophers Augustine of Hippo (354–430) and Thomas Aquinas[153] held that scriptures can have multiple interpretations on certain areas where the matters were far beyond their reach, therefore one should leave room for future findings to shed light on the meanings. The "Handmaiden" tradition, which saw secular studies of the universe as a very important and helpful part of arriving at a better understanding of scripture, was adopted throughout Christian history from early on.[154] Also the sense that God created the world as a self operating system is what motivated many Christians throughout the Middle Ages to investigate nature.[155]

Modern historians of science such as

Professor Noah J Efron says that "Generations of historians and sociologists have discovered many ways in which Christians, Christian beliefs, and Christian institutions played crucial roles in fashioning the tenets, methods, and institutions of what in time became modern science. They found that some forms of Christianity provided the motivation to study nature systematically..."[164] Virtually all modern scholars and historians agree that Christianity moved many early-modern intellectuals to study nature systematically.[165]

Individual scientists' beliefs

Prominent modern scientists advocating Christian belief include Nobel Prize–winning physicists

According to 100 Years of Nobel Prizes a review of Nobel prizes award between 1901 and 2000 reveals that (65.4%) of

Eastern Christianity

Many scholars of the House of Wisdom were of Christian background;[200] the

Catholic Church

While refined and clarified over the centuries, the

Galileo once stated "The intention of the

The influence of the Church on Western letters and learning has been formidable. The ancient texts of the Bible have deeply influenced Western art, literature and culture. For centuries following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, small monastic communities were practically the only outposts of literacy in Western Europe. In time, the Cathedral schools developed into Europe's earliest universities and the church has established thousands of primary, secondary and tertiary institutions throughout the world in the centuries since. The Church and clergymen have also sought at different times to censor texts and scholars. Thus different schools of opinion exist as to the role and influence of the Church in relation to western letters and learning.

The Catholic

One view, first propounded by

The Church's priest-scientists, many of whom were

Throughout history many of the

| Robert Grosseteste (1175–1253) |

Albertus Magnus (1200–1280) |

Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) |

Marin Mersenne (1588–1648) |

Christopher Clavius (1538–1612) |

Nicolas Steno (1638–1686) |

Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680) |

Gregor Mendel (1822–1884) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jesuit in science

The Jesuits have made numerous significant contributions to the development of science. For example, the Jesuits have dedicated significant study to earthquakes, and seismology has been described as "the Jesuit science".[217] The Jesuits have been described as "the single most important contributor to experimental physics in the seventeenth century".[218] According to Jonathan Wright in his book God's Soldiers, by the 18th century the Jesuits had "contributed to the development of pendulum clocks, pantographs, barometers, reflecting telescopes and microscopes, to scientific fields as various as magnetism, optics and electricity. They observed, in some cases before anyone else, the colored bands on Jupiter's surface, the Andromeda nebula and Saturn's rings. They theorized about the circulation of the blood (independently of Harvey), the theoretical possibility of flight, the way the moon affected the tides, and the wave-like nature of light."[219]

Protestant

Protestantism had an important influence on science. According to the

According of Scientific Elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States by

Thought and work ethic

The notion of "

Francisco de Vitoria, a disciple of Thomas Aquinas and a Catholic thinker who studied the issue regarding the human rights of colonized natives, is recognized by the United Nations as a father of international law, and now also by historians of economics and democracy as a leading light for the West's democracy and rapid economic development.[225] Joseph Schumpeter, an economist of the 20th century, referring to the Scholastics, wrote, "it is they who come nearer than does any other group to having been the 'founders' of scientific economics."[226] Other economists and historians, such as Raymond de Roover, Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson, and Alejandro Chafuen, have also made similar statements.

The Protestant concept of God and man allows believers to use all their God-given faculties, including the power of reason. That means that they are allowed to explore God's creation and, according to Genesis 2:15, make use of it in a responsible and sustainable way. Thus a cultural climate was created that greatly enhanced the development of the

Some mainline Protestant denominations such as

The rise of

Some academics have theorized that Lutheranism, the dominant traditional religion of the Nordic countries, had an effect on the development of social democracy there and the Nordic model. Schröder posits that Lutheranism promoted the idea of a nationwide community of believers and led to increased state involvement in economic and social life, allowing for nationwide welfare solidarity and economic co-ordination.[248][249][250] Esa Mangeloja says that the revival movements helped to pave the way for the modern Finnish welfare state. During that process, the church lost some of its most important social responsibilities (health care, education, and social work) as these tasks were assumed by the secular Finnish state.[251] Pauli Kettunen presents the Nordic model as the outcome of a sort of mythical "Lutheran peasant enlightenment", portraying the Nordic model as the result of a sort of "secularized Lutheranism";[252] however, mainstream academic discourse on the subject focuses on "historical specificity", with the centralized structure of the Lutheran church being but one aspect of the cultural values and state structures that led to the development of the welfare state in Scandinavia.[253]

Festivals

-

Saint Lucy's Day procession in Sweden

-

Easter eggs are a popular cultural symbol of Easter

Religious life

Roman Catholic theology enumerates seven sacraments:

In Christian belief and practice, a sacrament is a rite, instituted by Christ, that mediates grace, constituting a sacred mystery. The term is derived from the Latin word sacramentum, which was used to translate the Greek word for mystery. Views concerning both what rites are sacramental, and what it means for an act to be a sacrament vary among Christian denominations and traditions.[280]

The most conventional functional definition of a sacrament is that it is an outward sign, instituted by Christ, that conveys an inward, spiritual grace through Christ. The two most widely accepted sacraments are

Taken together, these are the

Today, most

Worship can be varied for special events like

Family life

Christian culture puts notable emphasis on the

Most

The

A

Cuisine

In mainstream Nicene Christianity, there is no restriction on kinds of animals that can be eaten.[308][309] This practice stems from Peter's vision of a sheet with animals, in which Saint Peter "sees a sheet containing animals of every description lowered from the sky."[310] Nonetheless, the New Testament does give a few guidelines about the consumption of meat, practiced by the Christian Church today; one of these is not consuming food knowingly offered to pagan idols,[311] a conviction that the early Church Fathers, such as Clement of Alexandria and Origen preached.[312] In addition, Christians traditionally bless any food before eating it with a mealtime prayer (grace), as a sign of thanking God for the meal they have.[313]

Slaughtering animals for food is often done without the

Some

Christian cooking combines the food of many cultures in which Christian have lived. A special

Cleanliness

The Bible has many rituals of purification relating to

Christianity has always placed a strong

Great

Contrary to popular belief

The

Christian pop culture

Christian pop culture (or Christian popular culture), is the

In modern urban mass societies, Christian pop culture has been crucially shaped by the development of industrial mass production, the introduction of new technologies of sound and image broadcasting and recording, and the growth of mass media industries—the film, broadcast radio and television, radio, video game, and the book publishing industries, as well as the print and electronic news media.

Items of Christian pop culture most typically appeal to a broad spectrum of Christians. Some argue that broad-appeal items dominate Christian pop culture because profit-making Christian companies that produce and sell items of Christian pop culture attempt to maximize their profits by emphasizing broadly appealing items. And yet the situation is more complex. To take the example of

Because the Christian pop industry is significantly smaller than the secular pop industry, a few organizations and companies dominate the market and have a strong influence over what is dominant within the industry.

Another source of Christian pop culture which makes it differ from pop culture is the influence from

Film industry

The

The 2014 film God's Not Dead is one of the all-time most successful independent Christian films[359] and the 2015 film War Room became a Box Office number-one film.[360]

Televangelism

Televangelism began as a uniquely American phenomenon, resulting from a

Some countries have more regulated media with either general restrictions on access or specific rules regarding religious broadcasting. In such countries, religious programming is typically produced by TV companies (sometimes as a regulatory or public service requirement) rather than private

Christianophile

A Christianophile is a person who expresses a strong interest in or appreciation for Christianity, Christian culture,

Christianity and Christian culture has a generally positive image in a number of non-Christian societies such as Hong Kong,[372] Macau,[373] India, Japan,[374][375][376] Lebanon,[377] Singapore,[378][379] South Korea,[380][381] and Taiwan.[382][383] In number of traditional Christian societies in Europe, there has been a revival of what has been called by some scholars "Christianophile", and a sympathy for Christianity and its culture, with politicians increasingly speaking of the "Christian roots and heritage" of their countries; this includes Austria,[384][385] France,[386] Hungary,[387] Italy,[388] Poland,[389] Russia,[389] Serbia,[389] Slovakia,[389] and the United Kingdom.[390]

See also

- Aristotelianism

- Astrotheology

- Assyrian culture

- Celtic Christianity

- Christianese

- Christian influences in Islam

- Christian values

- Culture of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Cynicism (philosophy)

- Gnosticism

- International law

- Judeo-Christian values

- Multiculturalism and Christianity

- Natural law

- Neoplatonism and Christianity

- Platonism

- Protestant culture

- Role of Christianity in civilization

- Stoicism

- Syriac Christianity

- The night of churches

References

- ISBN 9780198293880. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ "The historical march of the Arabs: the third moment".

- ISBN 978-0-567-21617-5.

- ^ Caltron J.H Hayas, Christianity and Western Civilization (1953), Stanford University Press, p.2: "That certain distinctive features of our Western civilization – the civilization of western Europe and of America— have been shaped chiefly by Judaeo – Graeco – Christianity, Catholic and Protestant."

- ^ a b Cambridge University Historical Series, An Essay on Western Civilization in Its Economic Aspects, p. 40: Hebraism, like Hellenism, has been an all-important factor in the development of Western Civilization; Judaism, as the precursor of Christianity, has indirectly had had much to do with shaping the ideals and morality of western nations since the christian era.

- ^ ISBN 9780813216836.

- ^ ISBN 9781351510721.

- ^ ISBN 9781136001666.

- ^ ISBN 0521814561.

Many of the scientists who contributed to these developments were Christians

- ^ ISBN 978-0191025136.

the Christian contribution to science has been uniformly at the top level, but it has reached that level and it has been sufficiently strong overall

- ^ ISBN 978-0830875276.

Many of the early leaders of the scientific revolution were Christians of various stripes, including Roger Bacon, Copernicus, Kepler, Francis Bacon, Galileo, Newton, Boyle, Pascal, Descartes, Ray, Linnaeus and Gassendi

- ^ "100 Scientists Who Shaped World History". Archived from the original on 19 November 2005. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "50 Nobel Laureates and Other Great Scientists Who Believe in God". Archived from the original on 24 May 2007. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ ISBN 978-1787203044.

Many prominent Catholic physicians and psychologists have made significant contributions to hypnosis in medicine, dentistry, and psychology.

- ^ "Religious Affiliation of the World's Greatest Artists". Archived from the original on 11 December 2005. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b "Wealthy 100 and the 100 Most Influential in Business". Archived from the original on 19 November 2005. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ ISBN 1405108991.

Virtually every major European composer contributed to the development of church music. Monteverdi, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, and Verdi are all examples of composers to have made significant contributions in this sphere. The Catholic church was without question one of the most important patrons of musical developments, and a crucial stimulus to the development of the western musical tradition.

- ISBN 978-1442219427.

The insights of Christian philosophy 'would not have happened without the direct or indirect contribution of Christian faith' (FR 76). Typical Christian philosophers include St. Augustine, St. Bonaventure, and St. Thomas Aquinas. The benefits derived from Christian philosophy are twofold.

- ISBN 978-0874627565.

Catholic thinkers contributed extensively to philosophy during the Nineteenth Century. Besides pioneering the revivals of Augustinianism and Thomism, they also helped to initiate such philosophical movements as Romanticism, Traditionalism, Semi-Rationalism, Spiritualism, Ontologism, and Integralism

- OCLC 370638.

- ISBN 978-0191025136.

Christians has also contributed greatly to the abolition of slavery, or at least to the mitigation of the rigour of servitude.

- ISBN 978-0-19-092154-5.

- ^ Davies, 477

- ^ Löffler, Klemens (1910). "Humanism". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. VII. New York: Robert Appleton Company. pp. 538–542.

- ISBN 978-1787203044.

In the centuries succeeding the Reformation the teaching of Protestantism was consistent on the nature of work. Some Protestant theologians also contributed to the study of economics, especially the nineteenth-century Scottish minister Thomas Chalmers.

- ^ "Religion of History's 100 Most Influential People". Archived from the original on 28 November 1999. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Religion of Great Philosophers". Archived from the original on 18 January 2000. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ISBN 978-0935047370

- ^ a b Riches 2000, chs. 1 and 4.

- ISBN 9780521889520.

The Bible is the most globally influential and widely read book ever written. ... it has been a major influence on the behavior, laws, customs, education, art, literature, and morality of Western civilization.

- ISBN 9780199759217.

- ^ a b Riches 2000, ch. 1.

- ISBN 9780521616645. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "christendom. §1.3 Scheidingen". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- ISBN 978-0-913836-90-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4051-9833-2.

- ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ISBN 978-0-19-829388-0. Archivedfrom the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- ^ ISBN 0-7486-0455-3, p.4

- ^ ISBN 9780226070803. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ a b Ferguson, Kitty Pythagoras: His Lives and the Legacy of a Rational Universe Walker Publishing Company, New York, 2008, (page number not available – occurs toward end of Chapter 13, "The Wrap-up of Antiquity"). "It was in the Near and Middle East and North Africa that the old traditions of teaching and learning continued, and where Christian scholars were carefully preserving ancient texts and knowledge of the ancient Greek language."

- ^ Rémi Brague, Assyrians contributions to the Islamic civilization Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Britannica, Nestorian

- ^ "Review of How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization by Thomas Woods, Jr". National Review Book Service. Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ^ Ware 1993, p. 8.

- ISBN 978-0-8042-0796-6.

- ISBN 978-0-88141-055-6.

- ^ Heussi, Karl (1956). Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, 11., Tübingen (Germany), pp. 317–319, 325–326

- ^ E. Marty, Martin (13 August 2022). "Protestantism's influence in the modern world". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Caltron J.H Hayas, Christianity and Western Civilization (1953), Stanford University Press, p. 2: "That certain distinctive features of our Western civilization—the civilization of western Europe and of America—have been shaped chiefly by Judaeo – Graeco – Christianity, Catholic and Protestant."

- S2CID 170111458.

- OCLC 44133076.

- ^ "Europe: A History". Goodreads. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. xix–xx

- ^ Verger 1999

- ^ "Valetudinaria". broughttolife.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ISBN 0-19-505523-3.

- ^ Karl Heussi, Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, 11. Auflage (1956), Tübingen (Germany), pp. 317–319, 325–326

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Forms of Christian education

- ^ ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. XIX–XX

- ^ ISBN 286847344X. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ISBN 0691128073, p. 68.

- ^ Woods 2005, p. 109.

- ^ Wright, Jonathan (2004). God's Soldiers: Adventure, Politics, intrigue and Power: A History of the Jesuits. HarperCollins. p. 200.

- ^ "Jesuit". Encyclopædia Britannica. 29 August 2023.

- ISBN 0-691-11436-6, page 123

- ^ Wallace, William A. (1984). Prelude, Galileo and his Sources. The Heritage of the Collegio Romano in Galileo's Science. NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-520-05538-4

- ISBN 978-0813515304.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Church and social welfare

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Care for the sick

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Property, poverty, and the poor,

- ^ Weber, Max (1905). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.

- ISBN 978-0-521-89057-1, pp. 189, 208

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Church and state

- ^ Banister Fletcher, History of Architecture on the Comparative Method.

- ^ Buringh, Eltjo; van Zanden, Jan Luiten: "Charting the 'Rise of the West': Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries", The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 69, No. 2 (2009), pp. 409–445 (416, table 1)

- ^ a b Eveleigh, Bogs (2002). Baths and Basins: The Story of Domestic Sanitation. Stroud, England: Sutton.

- ^ a b Christianity in Action: The History of the International Salvation Army p.16

- ^ Christianity has always placed a strong emphasis on hygiene:

- Warsh, Cheryl Krasnick; Strong-Boag, Veronica (2006). Children's Health Issues in Historical Perspective. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-88920-912-1.

... From Fleming's perspective, the transition to Christianity required a good dose of personal and public hygiene ...

- Cheryl Krasnick Warsh; Veronica Strong-Boag, eds. (2006). Children's Health Issues in Historical Perspective. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 315. ISBN 9780889209121.

... Thus bathing also was considered a part of good health practice. For example, Tertullian attended the baths and believed them hygienic. Clement of Alexandria, while condemning excesses, had given guidelines for Christians who wished to attend the baths ...

- Squatriti, Paolo (2002). Water and Society in Early Medieval Italy, AD 400–1000, Parti 400–1000. Cambridge University Press. p. 54. ISBN 9780521522069.

... but baths were normally considered therapeutic until the days of Gregory the Great, who understood virtuous bathing to be bathing "on account of the needs of body" ...

- Eveleigh, Bogs (2002). Baths and Basins: The Story of Domestic Sanitation. Stroud, England: Sutton.

- Bradley, Ian (2012). Water: A Spiritual History. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781441167675.

- Channa, Subhadra (2009). The Forger's Tale: The Search for Odeziaku. Indiana University Press. p. 284. ISBN 9788177550504.

A major contribution of the Christian missionaries was better health care of the people through hygiene. Soap, tooth–powder and brushes came to be used increasingly in urban areas.

- Thomas, John (2015). Evangelising the Nation: Religion and the Formation of Naga Political Identity. Routledge. p. 284. ISBN 9781317413981.

cleanliness and hygiene became an important marker of being identified as a Christian

- Warsh, Cheryl Krasnick; Strong-Boag, Veronica (2006). Children's Health Issues in Historical Perspective. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 315.

- ISBN 978-0-8028-4841-3.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica The tendency to spiritualize and individualize marriage

- ISBN 978-1-4443-9075-9.

...Christianity placed great emphasis on the family and on all members from children to the aged...

- ISBN 9781134365449.

- ^ Chadwick, Owen p. 242.

- ^ Hastings, p. 309.

- PMID 29644222.

- ^ Cameron 2009.

- ^ John Harvey, The Gothic World.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ T. Mathews, The early churches of Constantinople: architecture and liturgy (University Park, 1971); N. Henck, "Constantius ho Philoktistes?", Dumbarton Oaks Papers 55 (2001), 279–304 (available online Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Duffy, p. 133.

- ^ a b Kenneth Clarke; Civilisation, BBC, SBN 563 10279 9; first published 1969.

- ^ Verger, Jacques. "The Universities and Scholasticism", in The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume V c. 1198–c. 1300. Cambridge University Press, 2007, 257.

- ISBN 0-87249-376-8, pp. 126–7, 282–98

- ^ Gardner, p. 148

- ISBN 978-0-415-33526-3

- ^ a b Geoffrey Blainey; A Short History of Christianity; Penguin Viking; 2011

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Robert Grosseteste". Newadvent.org. 1 June 1910. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Albertus Magnus". Newadvent.org. 1 March 1907. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "Catholic Education" (PDF).

- ^ "Laudato Si". Vermont Catholic. 8 (4, 2016–2017, Winter): 73. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ Clifton E. Olmstead (1960), History of Religion in the United States, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., pp. 69–80, 88–89, 114–117, 186–188

- ^ M. Schmidt, Kongregationalismus, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band III (1959), Tübingen (Germany), col. 1770

- ^ McKinney, William. "Mainline Protestantism 2000". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 558, Americans and Religions in the Twenty-First Century (July 1998), pp. 57–66.

- ^ "The Harvard Guide: The Early History of Harvard University". News.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 22 July 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ "Increase Mather"., Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Princeton University Office of Communications. "Princeton in the American Revolution". Retrieved 24 May 2011. The original Trustees of Princeton University "were acting in behalf of the evangelical or New Light wing of the Presbyterian Church, but the College had no legal or constitutional identification with that denomination. Its doors were to be open to all students, 'any different sentiments in religion notwithstanding.'"

- ^ ISBN 0-231-13008-2.

- ^ "Duke University's Relation to the Methodist Church: the basics". Duke University. 2002. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

Duke University has historical, formal, on-going, and symbolic ties with Methodism, but is an independent and non-sectarian institution ... Duke would not be the institution it is today without its ties to the Methodist Church. However, the Methodist Church does not own or direct the University. Duke is and has developed as a private non-profit corporation which is owned and governed by an autonomous and self-perpetuating Board of Trustees.

- OCLC 4114776.

- ^ "The most and least educated U.S. religious group". Pew Research Center. 16 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Religion and Education Around the World" (PDF). Pew Research Center. 19 December 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "المسيحيون العرب يتفوقون على يهود إسرائيل في التعليم". Bokra. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ "biblical literature". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-111-83720-4.

- ^ "When the King Saved God". Vanity Fair. 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ "Why I want all our children to read the King James Bible". The Guardian. 20 May 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ "Best selling book of non-fiction". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Ryken, Leland. "How We Got the Best-Selling Book of All Time". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ "The battle of the books". The Economist. 22 December 2007.

- ISBN 0-7894-8043-3.

- ^ Mango 2007, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Ross, James F., "Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologiae (ca. 1273), Christian Wisdom Explained Philosophically", in The Classics of Western Philosophy: A Reader's Guide, (eds.) Jorge J. E. Gracia, Gregory M. Reichberg, Bernard N. Schumacher (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), p. 165. [1]

- ^ Roy Porter; The Greatest Benefit to Mankind - a Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present; Harper Collins; 1997; pp82-83

- ^ Roy Porter; The Greatest Benefit to Mankind - a Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present; Harper Collins; 1997; p.90.

- ^ PMID 3902734.

- S2CID 145378868.

- ^ Geoffrey Blainey; A Short History of Christianity; Penguin Viking; 2011; pp 214-215.

- ^ Roy Porter; The Greatest Benefit to Mankind - a Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present; Harper Collins; 1997; pp. 110-112

- S2CID 144793259.

- ^ Robert Calderisi; Earthly Mission - The Catholic Church and World Development; TJ International Ltd; 2013; p.40

- ^ "Catholic hospitals comprise one quarter of world's healthcare, council reports :: Catholic News Agency (CNA)". Catholic News Agency. 10 February 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ Hall, p. 100.

- ^ Murray, p. 45.

- Protestant Reformation in the 1520s. Christopher Hughes, in A.C. Grayling (ed.), Philosophy 2: Further through the Subject (Oxford University Press, 1998), covers philosophers from Augustine to Ockham. Jorge J.E. Gracia, in Nicholas Bunnin and E.P. Tsui-James (eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Philosophy, 2nd ed. (Blackwell, 2003), p. 620, identifies medieval philosophy as running from Augustine to John of St. Thomasin the 17th century. Anthony Kenny, A New History of Western Philosophy, Volume II: Medieval Philosophy (Oxford University Press, 2005), begins with Augustine and ends with the Lateran Council of 1512.

- ^ Gracia, p. 1

- ^ Charles Schmitt and Quentin Skinner (eds.), The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 1988), p. 5, loosely define the period as extending "from the age of Ockham to the revisionary work of Bacon, Descartes and their contemporaries."

- ^ Brian Copenhaver and Charles Schmitt, Renaissance Philosophy (Oxford University Press, 1992), p. 4: "one may identify the hallmark of Renaissance philosophy as an accelerated and enlarged interest, stimulated by newly available texts, in primary sources of Greek and Roman thought that were previously unknown or partially known or little read."

- ^ Jorge J.E. Gracia in Nicholas Bunnin and E.P. Tsui-James (eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Philosophy, 2nd ed. (Blackwell, 2002), p. 621: "the humanists ... restored man to the centre of attention and channeled their efforts to the recovery and transmission of classical learning, particularly in the philosophy of Plato."

- ^ Charles B. Schmitt and Quentin Skinner (eds.), The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy, pp. 61 and 63: "From Petrarch the early humanists learnt their conviction that the revival of humanae literae was only the first step in a greater intellectual renewal" "the very conception of philosophy was changing because its chief object was now man—man was at centre of every inquiry".

- ^ Richard Popkin, The History of Scepticism from Savonarola to Bayle (Oxford University Press, 2003).

- ^ Copenhaver and Schmitt, Renaissance Philosophy, pp. 274–284.

- ^ Schmitt and Skinner, The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy, pp. 430–452.

- ^ a b Religion and Science, John Habgood, Mills & Brown, 1964, pp., 11, 14–16, 48–55, 68–69, 90–91, 87

- ISBN 978-0-8006-6273-8.

- ^ Knight, Christopher C. (2008). "God's Action in Nature's World: Essays in Honour of Robert John Russell". Science & Christian Belief. 20 (2): 214–215.

- ISBN 0-8018-8401-2.

- ^ Grant 2006, p. 111-114

- ^ Grant 2006, p. 105-106

- ^ "What Time Is It in the Transept?". The New York Times. D. Graham Burnett book review of J.L.Heilbron's work, The Sun in the Church: Cathedrals as Solar Observatories. 24 October 1999. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ISBN 0-226-48214-6.

- ISBN 0-306-80637-1.

- ^ Pope John Paul II (September 1998). "Fides et Ratio (Faith and Reason), IV". Retrieved 15 September 2006.

- ISBN 0-8028-4772-2.

- ^ Harrison, Peter (8 May 2012). "Christianity and the rise of western science". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ Noll, Mark, Science, Religion, and A.D. White: Seeking Peace in the "Warfare Between Science and Theology" (PDF), The Biologos Foundation, p. 4, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2015, retrieved 14 January 2015

- ISBN 0521814561.

- ISBN 9780674057418.

- ISBN 9780674057418.

- Polski słownik biograficzny (Polish Biographical Dictionary), vol. XIV, Wrocław, Polish Academy of Sciences, 1969, p. 11.

- ISBN 0-521-56671-1.

- ^ "Because he would not accept the Formula of Concord without some reservations, he was excommunicated from the Lutheran communion. Because he remained faithful to his Lutheranism throughout his life, he experienced constant suspicion from Catholics." John L. Treloar, "Biography of Kepler shows man of rare integrity. Astronomer saw science and spirituality as one." National Catholic Reporter, 8 October 2004, p. 2a. A review of James A. Connor Kepler's Witch: An Astronomer's Discovery of Cosmic Order amid Religious War, Political Intrigue and Heresy Trial of His Mother, Harper San Francisco.

- ^ Richard S. Westfall – Indiana University The Galileo Project. (Rice University). Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- ^ "The Boyle Lecture". St. Marylebow Church.

- ^ Bacon, Francis (1625). The Essayes Or Covnsels, Civill and Morall, of Francis Lo. Vervlam, Viscovnt St. Alban. London. p. 90. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ Leibniz on the Trinity and the Incarnation: Reason and Revelation in the Seventeenth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007, pp. xix–xx).

- ^ Dunnington 2004, p. 300.

- OCLC 53933110.

- ^ Swedenborg, E. The True Christian Religion, particularly sections 163–184 (New York: Swedenborg Foundation, 1951).

- ^ "Gli scienziati cattolici che hanno fatto lItalia (Catholic scientists who made Italy)". Zenit. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013.

- ^ Grimaux, Edouard. Lavoisier 1743–1794. (Paris, 1888; 2nd ed., 1896; 3rd ed., 1899), page 53.

- ^ "John Dalton". Science History Institute. June 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- doi:10.1119/1.14636.

- ^ Hutchinson, Ian (2006) [January 1998]. "James Clerk Maxwell and the Christian Proposition". Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ McCartney & Whitaker (2002), reproduced on Institute of Physics website

- ^ Vallery-Radot, Maurice (1994). Pasteur. Paris: Perrin. pp. 377–407.

- ^ Cantor, pp. 41–43, 60–64, and 277–280.

- ISBN 9780226068596. "Both Lord Rayleigh and J. J. Thomson were Anglicans."

- ^ Seeger, Raymond. 1986. "J. J. Thomson, Anglican," in Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith, 38 (June 1986): 131–132. The Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation. ""As a Professor, J.J. Thomson did attend the Sunday evening college chapel service, and as Master, the morning service. He was a regular communicant in the Anglican Church. In addition, he showed an active interest in the Trinity Mission at Camberwell. With respect to his private devotional life, J.J. Thomson would invariably practice kneeling for daily prayer, and read his Bible before retiring each night. He truly was a practicing Christian!" (Raymond Seeger 1986, 132)."

- ^ "Christian Influences in the Sciences". rae.org. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ "World's Greatest Creation Scientists from Y1K to Y2K". creationsafaris.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- S2CID 39722460.

- ^ Baruch A. Shalev (2003), 100 Years of Nobel Prizes, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, p. 57

- ^ a b c d Shalev, Baruch (2005). 100 Years of Nobel Prizes. p. 59

- ^ "Byzantine Medicine - Vienna Dioscurides". Antiqua Medicina. University of Virginia. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2007.

- ^ George Saliba (27 April 2006). "Islamic Science and the Making of Renaissance Europe". Library of Congress. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ISBN 978-3-11-013574-9.

- ISBN 0-87220-563-0.)

- Georgios Plethonfor their devotion to ancient philosophy.

- ISBN 0-87220-563-0.)

- JSTOR 1291170.

- ^ Kaser, Karl The Balkans and the Near East: Introduction to a Shared History p. 135.

- ^ Yazberdiyev, Dr. Almaz Libraries of Ancient Merv Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Dr. Yazberdiyev is Director of the Library of the Academy of Sciences of Turkmenistan, Ashgabat.

- ^ Hyman and Walsh Philosophy in the Middle Ages Indianapolis, 1973, p. 204' Meri, Josef W. and Jere L. Bacharach, Editors, Medieval Islamic Civilization Vol.1, A-K, Index, 2006, p. 304.

- ^ Hyman and Walsh Philosophy in the Middle Ages Indianapolis, 3rd edition, p. 216

- ^ Meri, Josef W. and Jere L. Bacharach, Editors, Medieval Islamic Civilization Vol.1, A – K, Index, 2006, p. 451

- ^ The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 22:2 Mehmet Mahfuz Söylemez, The Jundishapur School: Its History, Structure, and Functions, p.3.

- ISBN 978-0-7914-5737-5.

- ISBN 978-84-600-8154-8.

- ^ Byzantines in Renaissance Italy

- ^ "Fall of Constantinople". Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 May 2023.

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia". New Advent. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ISBN 0-521-58841-3.

- John Paul II, 3 October 1981 to the Pontifical Academy of Science, "Cosmology and Fundamental Physics"

- ^ King, David (1995). "A forgotten Cistercian system of numerical notation". Citeaux Commentarii Cistercienses. 46 (3–4): 183–217.

- OCLC 630115876.

- ^ a b Rob Baedeker (24 March 2008). "Good Works: Monks build multimillion-dollar business and give the money away". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- ^ Gimpel, p 67. Cited by Woods.

- ^ Woods, p 33

- ^ a b Herbert Thurston. "Cistercians in the British Isles". Catholic Encyclopedia. NewAdvent.org. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ISBN 0-691-12807-3, p. 68.

- ISBN 978-052005-538-4.

- ISBN 978-038550-080-7.

- ^ ISBN 9781405105958

- ^ Gregory, Andrew (1998), Handout for course 'The Scientific Revolution' at The Scientific Revolution

- ^ Becker, George (1992), "The Merton Thesis: Oetinger and German Pietism, a significant negative case". Sociological Forum (Springer) 7 (4), pp. 642–660

- ^ a b c d Harriet Zuckerman, Scientific Elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States New York, The Free Press, 1977, p.68: Protestants turn up among the American-reared laureates in slightly greater proportion to their numbers in the general population. Thus 72 percent of the seventy-one laureates but about two-thirds of the American population were reared in one or another Protestant denomination-)

- ^ J. Le Goff, Marchands et banquiers au Moyen Âge, Puf Quadrige, 2011, p. 75

- ^ de Torre, Fr. Joseph M. (1997). "A Philosophical and Historical Analysis of Modern Democracy, Equality, and Freedom Under the Influence of Christianity". Catholic Education Resource Center.

- ^ Schumpeter, Joseph (1954). History of Economic Analysis. London: Allen & Unwin.

- ^ Gerhard Lenski (1963), The Religious Factor: A Sociological Study of Religion's Impact on Politics, Economics, and Family Life, Revised Edition, A Doubleday Anchor Book, Garden City, N.Y., pp.348–351

- ISBN 978-0-19-516247-9, p. 52

- ^ Jan Weerda, Soziallehre des Calvinismus, in Evangelisches Soziallexikon, 3. Auflage (1958), Stuttgart (Germany), col. 934

- ^ Eduard Heimann, Kapitalismus, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band III (1959), Tübingen (Germany), col. 1136–1141

- ^ Hans Fritz Schwenkhagen, Technik, in Evangelisches Soziallexikon, 3. Auflage, col. 1029–1033

- ^ Georg Süßmann, Naturwissenschaft und Christentum, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band IV, col. 1377–1382

- ^ C. Graf von Klinckowstroem, Technik. Geschichtlich, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band VI, col. 664–667

- ^ Kim, Sung Ho (Fall 2008). "Max Weber". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, CSLI, Stanford University. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ^ a b c B. Drummond Ayres Jr. (19 December 2011). "The Episcopalians: An American Elite With Roots Going Back to Jamestown". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ Irving Lewis Allen, "WASP—From Sociological Concept to Epithet", Ethnicity, 1975 154+

- S2CID 146933599.

- ^ Baltzell (1964). The Protestant Establishment. New York, Random House. p. 9.

- ISBN 9781469626987.

The names of fashionable families who were already Episcopalian, like the Morgans, or those, like the Fricks, who now became so, goes on interminably: Aldrich, Astor, Biddle, Booth, Brown, Du Pont, Firestone, Ford, Gardner, Mellon, Morgan, Procter, the Vanderbilt, Whitney. Episcopalians branches of the Baptist Rockefellers and Jewish Guggenheims even appeared on these family trees.

- ISBN 9780801444708.

By the late nineteenth century, one of the strongest bulwarks of Brahmin power was Harvard University. Statistics underscore the close relationship between Harvard and Boston's upper strata.

- ISBN 9780838632970.

- ISBN 9780742571983.

- ISBN 9781412830751.

- ^ Percy Ernst Schramm, Neun Generationen: Dreihundert Jahre deutscher "Kulturgeschichte" im Lichte der Schicksale einer Hamburger Bürgerfamilie (1648–1948). Vol. I and II, Göttingen 1963/64.

- S2CID 144579790.

- ^ Crum, Roger J. Severing the Neck of Pride: Donatello's "Judith and Holofernes" and the Recollection of Albizzi Shame in Medicean Florence . Artibus et Historiae, Volume 22, Edit 44, 2001. pp. 23–29.

- ^ Negotiating the French Pox in Early Modern Germany by Claudia Stein

- ^ Schröder, Martin (2013). Integrating Varieties of Capitalism and Welfare State Research. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 96, 144–145, 149, 155, 157.

- ISBN 9781849809603– via Google Books.

- ^ Kettunen, Pauli (2010). "The Sellers of Labour Power as Social Citizens: A Utopian Wage Work Society in the Nordic Visions of Welfare" (PDF). NordWel Studies in Historical Welfare State Research: 16–45.

- ISBN 9789518581355.

- ISBN 978-87-7184-416-0– via Google Books.

- ISBN 9781861894618– via Google Books.

- ^ "Christmas Markets in Germany and Europe". The German Way & More. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ a b Fortescue, Adrian (1912). "Christian Calendar". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Hickman. Handbook of the Christian Year.

- ^ "The Global Religious Landscape | Christians". Pew Research Center. 18 December 2012. Archived from the original on 10 March 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "Christmas Strongly Religious For Half in U.S. Who Celebrate It". Gallup, Inc. 24 December 2010. Archived from the original on 7 December 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- ^ Canadian Heritage – Public holidays Archived 24 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine – Government of Canada. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ 2009 Federal Holidays Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine – U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ Bank holidays and British Summer time Archived 15 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine – HM Government. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-4291-0896-6.

- ^ Nick Hytrek, "Non-Christians focus on secular side of Christmas" Archived 14 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Sioux City Journal, 10 November 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2009.

- ^ "Poll: In a changing nation, Santa endures". Associated Press. 22 December 2006. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- ISBN 978-0473276812.

Easter Day, also known as Resurrection Sunday, marks the high point of the Christian year. It is the day that we celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead.

- ISBN 978-0814651759. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

Orthodox, Catholic, and all Reformed churches in the Middle East celebrate Easter according to the Eastern calendar, calling this holy day "Resurrection Sunday," not Easter.

- ISBN 978-0838906958.

Easter is the central celebration of the Christian liturgical year. It is the oldest and most important Christian feast, celebrating the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. The date of Easter determines the dates of all movable feasts except those of Advent.

- ISBN 0-19-517154-3.

- ISBN 9780198607663.

- ISBN 978-0748753208. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

Easter eggs are used as a Christian symbol to represent the empty tomb. The outside of the egg looks dead but inside there is new life, which is going to break out. The Easter egg is a reminder that Jesus will rise from His tomb and bring new life. Eastern Orthodox Christians dye boiled eggs red to represent the blood of Christ shed for the sins of the world.

- ^ The Guardian, Volume 29. H. Harbaugh. 1878. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

Just so, on that first Easter morning, Jesus came to life and walked out of the tomb, and left it, as it were, an empty shell. Just so, too, when the Christian dies, the body is left in the grave, an empty shell, but the soul takes wings and flies away to be with God. Thus you see that though an egg seems to be as dead as a stone, yet it really has life in it; and also it is like Christ's dead body, which was raised to life again. This is the reason we use eggs on Easter. (In olden times they used to color the eggs red, so as to show the kind of death by which Christ died, – a bloody death.)

- ISBN 978-0435306915. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

Red eggs are given to Orthodox Christians after the Easter Liturgy. They crack their eggs against each other's. The cracking of the eggs symbolizes a wish to break away from the bonds of sin and misery and enter the new life issuing from Christ's resurrection.

- ^ Collins, Cynthia (19 April 2014). "Easter Lily Tradition and History". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

The Easter Lily is symbolic of the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Churches of all denominations, large and small, are filled with floral arrangements of these white flowers with their trumpet-like shape on Easter morning.

- ^ Schell, Stanley (1916). Easter Celebrations. Werner & Company. p. 84.

We associate the lily with Easter, as pre-eminently the symbol of the Resurrection.

- ^ Luther League Review: 1936–1937. Luther League of America. 1936.

- ISBN 978-0819225757. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

In parts of Europe, the eggs were dyed red and were then cracked together when people exchanged Easter greetings. Many congregations today continue to have Easter egg hunts for the children after the services on Easter Day.

- ^ The Church Standard, Volume 74. Walter N. Hering. 1897. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

When the custom was carrierd over into Christian practice the Easter eggs were usually sent to the priests to be blessed and sprinked with holy water. In later times the coloring and decorating of eggs was introduced, and in a royal roll of the time of Edward I., which is preserved in the Tower of London, there is an entry of 18d. for 400 eggs, to be used for Easter gifts.

- ISBN 978-1609577650. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

So what preparations do most Christians and non-Christians make? Shopping for new clothing often signifies the belief that Spring has arrived, and it is a time of renewal. Preparations for the Easter Egg Hunts and the Easter Ham for the Sunday dinner are high on the list too.

- ^ Cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1210 Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Cross/Livingstone. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. p. 1435f.

- ISBN 9780195176322.

Uniformly practiced by Jews, Muslims, and the members of Coptic, Ethiopian, and Eritrean Orthodox Churches, male circumcision remains prevalent in many regions of the world, particularly Africa, South and East Asia, Oceania, and Anglosphere countries.

- ^ Customary in some Coptic and other churches:

- "The Coptic Christians in Egypt and the Ethiopian Orthodox Christians— two of the oldest surviving forms of Christianity— retain many of the features of early Christianity, including male circumcision. Circumcision is not prescribed in other forms of Christianity ... Some Christian churches in South Africa oppose the practice, viewing it as a pagan ritual, while others, including the Nomiya church in Kenya, require circumcision for membership and participants in focus group discussions in Zambia and Malawi mentioned similar beliefs that Christians should practice circumcision since Jesus was circumcised and the Bible teaches the practice."

- "The decision that Christians need not practice circumcision is recorded in Acts 15; there was never, however, a prohibition of circumcision, and it is practiced by Coptic Christians." "circumcision", The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001–05.

- ISBN 9781567206913.

For most part, Christianity dose not require circumcision of its followers. Yet, some Orthodox and African Christian groups do require circumcision. These circumcisions take place at any point between birth and puberty.

- ISBN 9781438110387.

It is obligatory among Jews, Muslims, and Coptic Christians. Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant Christians do not require circumcision. Starting in the last half of the 19th century, however, circumcision also became common among Christians in Europe and especially in North America.

- ISBN 9780812292510.

Christian theology generally interprets male circumcision to be an Old Testament rule that is no longer an obligation ... though in many countries (especially the United States and Sub-Saharan Africa, but not so much in Europe) it is widely practiced among Christians

- ISBN 9781449648756.

Neonatal circumcision is the general practice among Jews, Christians, and many, but not all Muslims.

- ISBN 9781118665695.

Although it is mostly common and required in male newborns with Moslem or Jewish backgrounds, certain Christian-dominant countries such as the United States also practice it commonly.

- ISBN 9780190272432.

male circumcision is still observed among Ethiopian and Coptic Christians, and circumcision rates are also high today in the Philippines and the US.

- ISBN 9781108435529.

Christians in Africa, for instance, often practise infant male circumcision.

- ^ Nga, Armelle (30 December 2019). "The Ritual of Circumcision in Africa: The Case of South Africa". Africanews.

This practice is old and widespread among African Christians with very close links to their beliefs. It can be executed traditionally or in hospital.

- ISBN 9781606083420.

Although it is stated that circumcision is not a sacrament necessary for salvation, this rite is accepted for the Ethiopian Jacobites and other Middle Eastern Christians.

- ISBN 9780521769372.

On the Coptic Christian practice of male circumcision in Egypt, and on its practice by other Christians in western Asia.

- ^ "Circumcision protest brought to Florence". Associated Press. 30 March 2008.

However, the practice is still common among Christians in the United States, Oceania, South Korea, the Philippines, the Middle East and Africa. Some Middle Eastern Christians actually view the procedure as a rite of passage.

- ISBN 9781317461098.

For instance, the majority of South Koreans, Americans, and Filipinos, as well as African Christians, practice circumcision.

- ISBN 9781610698757.

- ISBN 9781444390759.

Christianity placed great emphasis on the family and on all members from children to the aged

- ^ "The Collapse of Marriage by Don Browning – The Christian Century". Religion-online.org. 7 February 2006. pp. 24–28. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ISBN 9781134365449.

in cultures with stronger 'extended family traditions', such as Asian and Catholic countries

- ^ Major Branches of Religions Ranked by Number of Adherents

- ISBN 978-0-7876-6612-5.

- ^ "Circumcision". Columbia Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. 2011.

- ^ Vivian C. Fox, "Poor Children's Rights in Early Modern England", Journal of Psychohistory, January 1996, Vol. 23 Issue 3, pp 286–306

- ^ "Children of the Reformation". Touchstone. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- ^ "Onan's Onus". Touchstone. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- OCLC 40185703

- ^ Bushman (2008, p. 59) (In the temple, husbands and wives are sealed to each other for eternity. The implication is that other institutional forms, including the church, might disappear, but the family will endure); "Mormons in America". Pew Research Center. January 2012. (A 2011 survey of Mormons in the United States showed that family life is very important to Mormons, with family concerns significantly higher than career concerns. Four out of five Mormons believe that being a good parent is one of the most important goals in life, and roughly three out of four Mormons put having a successful marriage in this category); "New Pew survey reinforces Mormons' top goals of family, marriage". Deseret News. 12 January 2012.; See also: "The Family: A Proclamation to the World".

- ^ a b c [Religion and Living Arrangements Around the World: Muslims and Hindus have larger households than Christians and religious 'nones,' in patterns influenced by regional norms], Pew Research Center, 12 December 2019

- ISBN 978-1-4094-7813-3.

Before Christianity, they could not eat certain things from certain animals (uumajuit), but after eating they can now do anything they want to.

- ISBN 978-1-58558-053-8.

The eating of animals is not forbidden. The Scriptures do not forbid the eating and partaking of animals. This does not mean that all animals are to be eaten (Mark 7:19; Acts 11:9; 1 Tim. 4:4). It is clear in the Scriptures that we are not supposed to eat animals that are alive or with blood (Gen. 9:2–4; Deut. 12:16, 23–24).

- ISBN 978-0-19-974113-7. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

In the meantime, Peter in Joppa has a middday vision in which he sees a sheet containing animals of every description lowered from the sky. He hears a voice from heaven telling him to "kill and eat." Peter is naturally taken aback, because eating some of these animals would mean breaking the Jewish rules about kosher foods. But then he hears a voice that tells him, "What God has cleansed, you must not call common [unclean]" (that is, you do not need to refrain from eating nonkosher foods; 10: 15). The same sequence of events happens three times.

- ^ "The Weaker Brother". Third Way. 25 (10): 25. December 2002.

Christ came for the Gentiles as well as the Jews (the real meaning of that vision in Acts 10:9;16) but he also calls us to look out for each other and not do things that will cause our brothers and sisters to stumble. In Corinthians Paul urges the believers to consider not eating meat when with people who assume that meat must be offered to idols before consumption: 'Food will not bring us close to God,' he writes. 'We are no worse off if we do not eat, and no better off if we do. But take care that this liberty of yours does not somehow become a stumbling block for the weak.' (1 Corinthians 8:8–9)

- ISBN 978-90-04-23478-9.

Clement of Alexandria and Origen also forbid eating meat dedicated to idolatry and partaking in meals with demons, which, by association, are the meals of fornicators and idolatrous adulterers. Marcianus Aristides merely testifies that Christians do not eat what has been sacrificed to idols; and Hippolytus only notes the interdiction against eating such food.

- ^ Deem, Rich (21 June 2008). "Should Christians Eat Meat or Should We Be Vegetarians?". Evidence for God from Science. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

Later, laws were instituted that declared certain meats to be "clean" and others to be "unclean". The system provided a means of proving one's obedience to God and had some health benefits. After Jesus Christ came, God declared all meats to be clean. Current slaughterhouse practices comply with the dictate to remove the blood, so virtually all meat today is acceptable to eat according to God.

- ISBN 978-0-520-92301-0.

The Christians do "Basema ab wawald wamanfas qeeus ahadu amlak" [in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit one God] and then slaughter. The Jews say "Baruch yitharek amlak yisrael" [Blessed is the King (God) of Israel].

- ISBN 978-0-300-13359-2.

By contrast, the most common mode of slaughtering four-legged animals among Christians in the nineteenth century was through the deliverance of a stunning blow to the head, usually with a mallet or poleax.

- ISBN 978-1-135-18832-0.

The Armenian and other Orthodox rituals of slaughter display obvious links with shechitah, Jewish kosher slaughter.

- ISBN 978-0-8010-3832-7.

- ISBN 978-1-59056-009-9.

Nevertheless, toward the end of the chapter, Paul suggests that even Christians with strong faith may want to abstain from eating meat offered to pagan deities if any chance that their example will tempt fellow Christians of weaker faith into inadvertent idolatry. He concludes by saying, "Therefore, if food causes my brother to stumble, I will never eat meat again, so that I will not cause my brother to stumble." (1 Corinthians 8:13)

- ISBN 978-1-4504-2454-7.

Traditional Hindus and Trappist monks adopt vegetarian diets as a practice of their faith.

- ISBN 978-0-89862-616-2.

Seventh-Day Adventists are also urged, but not required, to avoid eating meat and highly spiced food (Snowdon, 1988).

- ^ "What does The United Methodist Church say about fasting?". The United Methodist Church. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-520-07085-1. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

The main legally enforced prohibition in both Catholic and Anglican countries was that against meat. During Lent, the most prominent annual season of fasting in Catholic and Anglican churches, authorities enjoined abstinence from meat and sometimes 'white meats' (cheese, milk, and eggs); in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England butchers and victuallers were bound by heavy recognizances not to slaughter or sell meat on the weekly 'fish days,' Friday and Saturday.

- ISBN 978-1-4514-0774-7.

Of the Eating of Meat: One should abstain from the eating of meat on Fridays and Saturdays, also in fasts, and this should be observed as an external ordinance at the command of his Imperial Majesty.

- ISBN 978-0-89870-384-9. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

In the Orthodox groups, on ordinary Wednesdays and Fridays no meat, olive oil, wine, or fish can be consumed.

- ISBN 978-0-684-82314-0.

Although the Jewish, Roman Catholic, Orthodox, Episcopal, and Lutheran traditions generally allow moderate drinking for those who can do so, it is simply incorrect to accuse them of condoning drunkenness.

- ISBN 978-0-495-56609-0.

Protestants who called themselves "fundamentalists" (they believed in the literal truth of the Bible--Baptists, Methodists, Pentecostals) were dry.

- ISBN 978-0-313-32362-1.

Drunkenness was biblically condemned, and all denominations disciplined drunken members.

- ISBN 978-0-664-22589-6.

For most of Christian history, as in the Bible, moderate drinking of alcohol was taken for granted while drunkenness was condemned.

- ^ Broomfield, Andrea (2007) Food and cooking in Victorian England: a history pp.149–150. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007

- ^ Muir, Frank (1977) Christmas customs & traditions p.58. Taplinger Pub. Co., 1977

- ^ "Is the Church of Ethiopia a Judaic Church ?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ "THE ORIGIN AND HISTORY OF THE ETHIOPIAN ORTHODOX TEWAHEDO CHURCH LITURGY". Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ISBN 9780889209121.

From Fleming's perspective, the transition to Christianity required a good dose of personal and public hygiene

- ISBN 9780889209121.

Thus bathing also was considered a part of good health practice. For example, Tertullian attended the baths and believed them hygienic. Clement of Alexandria, while condemning excesses, had given guidelines for Christian] who wished to attend the baths

- ISBN 978-0739174531.

Clement of Alexandria (d. c. 215 CE) allowed that bathing contributed to good health and hygiene ... Christian skeptics could not easily dissuade the baths' practical popularity, however; popes continued to build baths situated within church basilicas and monasteries throughout the early medieval period

- ^ ISBN 9780521522069.

but baths were normally considered therapeutic until the days of Gregory the Great, who understood virtuous bathing to be bathing 'on account of the needs of body'

- ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- OCLC 501833155

- ISBN 9781440862328.

Public baths were common in the larger towns and cities of Europe by the twelfth century.

- ISBN 9781843831464.

The evidence of early medieval laws that enforced punishments for the destruction of bathing houses suggests that such buildings were not rare. That they ... took a bath every week. At places in southern Europe, Roman baths remained in use or were even restored ... The Paris city scribe Nicolas Boileau noted the existence of twenty-six public baths in Paris in 1272

- ISBN 9780838633915.

- ^ ISBN 9781441167675.

- ^ Melissa Snell. "The Bad Old Days - Weddings and Hygiene". About.com Education. Archived from the original on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ "The Great Famine and the Black Death – 1315–1317, 1346–1351 – Lectures in Medieval History – Dr. Lynn H. Nelson, Emeritus Professor, Medieval History, KU". Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ^ "Middle Ages Hygiene". Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ISBN 0-8247-9394-3.

- ^ History of The Salvation Army – Social Services of Greater New York, retrieved 30 January 2007. Archived 7 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 9780807849354. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ISBN 9780721625973.

- ISBN 9780721625973.

Douching is commonly practiced in Catholic countries. The bidet ... is still commonly found in France and other Catholic countries.

- ISBN 978-8866490395.

- ^ "Bidets in Finland"

- ISBN 978-1-4094-6755-7.

- ^ "Christian Movies at the Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Christian". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ^ Chen, Sandie Angulo (15 January 2010). "Will Christian Audiences Embrace Denzel's 'Book of Eli'?". Moviefone. Archived from the original on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ^ Flores, Terry (7 April 2015). "Oscar-Nommed Timothy Reckart to Make Feature Directing Debut on Sony Toon (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ISBN 978-1476665993.

- ^ Jeannie Law (December 2016). "'God's Not Dead 3' Is in the Works, Says Actor-Producer David AR White (Interview)". The Christian Post.

- ^ Simanton, Keith (6 September 2015). "Weekend Report -'War Room' Walks to #1". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ Stewart, Tim (13 January 2015). "televangelism". Dictionary of Christianese. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "Bishop Fulton Sheen: The First 'Televangelist'". Time. 14 April 1952.

- ^ "S. Parkes Cadman dies in coma at 71" (PDF). The New York Times. 12 July 1936. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ "Radio Religion". Time. 21 January 1946. Archived from the original on 25 January 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ Elaine Woo (2 December 2013). "Paul Crouch dies at 79; founder of the Trinity Broadcasting Network". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

He bought more television stations, then piled on cable channels and eventually satellites until he had built the world's largest Christian television system

- ISBN 9780415945387.

- ISBN 9780582502642.

- ^ Henry Liddell, Robert Scott, Henry Jones, and Roderick McKenzie. A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996. pp. 1189, 1939.

- ISBN 9781317562016.

- ISBN 9780853458937.

- ISBN 9780802869852.

- ^ Shun-hing Chan. Rethinking Folk Religion in Hong Kong: Social Capital, Civic Community and the State Archived 1 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Hong Kong Baptist University.

- ISBN 978-988-8028-54-2. Archivedfrom the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-57181-108-0.

- S2CID 144740841.

- ^ "A Little Faith: Christianity and the Japanese". Nippon.com: Your Doorway to Japan. 22 November 2019.

Christian culture in general has a positive image.

- ^ Kaufman, Asher "Tell Us Our History': Charles Corm, Mount Lebanon and Lebanese Nationalism" pages 1-28 from Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 40, No. 3, May 2004 page 2.

- S2CID 144728013.

- S2CID 144728013.

- ^ Sukman, Jang (2004). "Historical Currents and Characteristics of Korean Protestantism after Liberation". Korea Journal. 44 (4): 133–156.

- ISBN 9781416561248.

- ISBN 9780813386324.

- ISBN 9781403970206.

- ISBN 9781317931737.

- ^ "Sebastian Kurz: In New Yorks antiquierter Artusrunde". diepresse.com (in German). 27 September 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ISBN 9781317931737.

- ^ "Hungary's Orban calls for central Europe to unite around Christian roots". NBC News. 20 August 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ Parlato, Vittorio (2010). "Le chiese ortodosse in Italia, oggi". Studi Urbinati, A - Scienze giuridiche, politiche ed economiche. 61 (3): 483–501.

- ^ ISBN 9781857431377.